The Strand Magazine, July 1914

T

was with a start that Roland Bleke realized that the girl

at the other end of the bench was crying. For the last few minutes, as far as

his preoccupation allowed him to notice them at all, he had been attributing

the subdued sniffs to a summer cold.

T

was with a start that Roland Bleke realized that the girl

at the other end of the bench was crying. For the last few minutes, as far as

his preoccupation allowed him to notice them at all, he had been attributing

the subdued sniffs to a summer cold.

He was embarrassed. He blamed the fate that had led him to this particular bench, and also the economy which had caused him to select a bench instead of taking a pennyworth of green chair—an economy all the more ridiculous because his reason for sitting down at all was that he wished to give himself up to quiet deliberation on the question of what on earth he was to do with two hundred and fifty thousand pounds, to which figure his fortune had now risen.

It was an intermittent source of annoyance to him that he could not succeed entirely in shaking off his old prudent self. Here he was with wealth beyond the dreams of avarice—at any rate, of his own avarice—and yet he still kept catching himself in the act of approaching the world from the point of view of a provincial seed-merchant’s second clerk. He longed to live with a gay spaciousness, but habit was occasionally too strong for him. Sometimes he would ask himself despairingly if the rules of the new life were not too hard to learn; and for some days after one of these black moments he was apt to behave like a largesse-distributing monarch gone mad. Waiters, porters, cabmen, and others who came within reach of him at such times would dream of retiring with fortunes.

The sniffs continued. Roland’s discomfort increased. Chivalry had always been his weakness. In the old days, on a hundred and forty pounds a year, he had had few opportunities of indulging himself in this direction; but now it seemed to him sometimes that the whole world was crying out for assistance. When the world gets within earshot of a chivalrous young man with plenty of spare cash, it is not apt to be reticent.

Should he speak to her? He wanted to; but only a few days ago his eye had been caught by the placard of a weekly paper bearing the title of Squibs, on which in large letters was the legend, “Men Who Speak to Girls,” and he had gathered that the accompanying article was a denunciation rather than a eulogy of these individuals. On the other hand, she was obviously in distress.

Another sniff decided him.

“I say, you know,” he said.

What he had meant to say was, “Pardon me, but you appear to be in trouble. Is there anything I can do for you?” But the difference between life and the stage is that in life one’s lines never come out quite right at the first performance.

The girl looked at him. She was small, and at the present moment had that air of the floweret surprised while shrinking which adds a good thirty-three per cent. to a girl’s attractions. Her nose, he noted, was delicately tip-tilted. A certain pallor added to her beauty. Roland’s heart executed the opening steps of a buck-and-wing dance.

“Pardon me,” he went on, “but you appear to be in trouble. Is there anything I can do for you?”

She looked at him again—a keen look which seemed to get into Roland’s soul and walk about it with a search-light. Then, as if satisfied by the inspection, she spoke.

“No, I don’t think there is,” she said, “unless you happen to be the proprietor of a weekly paper with a Woman’s Page, and need an editress for it.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Well, that’s all anyone could do for me: give me back my work or give me something else of the same sort.”

“Oh, have you lost your job?”

“I have. So would you mind going away, because I want to go on crying, and I do it better alone! You won’t mind my turning you out, I hope, but I was here first, and there are heaps of other benches.”

“No, but wait a minute. I want to hear about this. I might be able—what I mean is—think of something. Tell me all about it.”

There is no doubt that the possession of two hundred and fifty thousand pounds tones down a diffident man’s diffidence. Roland began to feel almost masterful.

“Why should I?”

“Why shouldn’t you?”

“There’s something in that,” said the girl, reflectively. “After all, you might know somebody. Well, as you want to know, I have just been discharged from a paper called Squibs. I used to edit the Woman’s Page.”

“By Jove, did you write that article on ‘Men Who Speak——’?”

The hard manner in which she had wrapped herself as in a garment vanished instantly. Her eyes softened. She even blushed.

“You don’t mean to say you read it? I didn’t think anyone read Squibs.”

“Read it!” cried Roland, recklessly abandoning truth. “I should jolly well think so. I know it by heart. Do you mean to say that, after an article like that, they sacked you?”

“Oh, they didn’t send me away for incompetence. It was simply because they couldn’t afford to keep me on. Mr. Petheram was very nice about it.”

“Who’s Mr. Petheram?”

A slight twinge—it would be exaggeration to call it jealousy—disturbed Roland’s enjoyment of the conversation. Somehow he did not like the idea of this girl being on speaking terms with other men.

For the first time she smiled.

“Mr. Petheram’s everything. He calls himself the editor, but he’s really everything except office-boy, and I expect he’ll be that next week. When I started with the paper there was quite a large staff. But it got whittled down by degrees till there were only Mr. Petheram and myself. It was like the crew of the Nancy Bell. They got eaten one by one, till I was the only one left. And now I’ve gone. Mr. Petheram is doing the whole paper now.”

“He must be clever.”

“He’s a genius.”

“How is it that he can’t get anything better to do?” he said.

“He has done lots of better things. He used to be at Carmelite House, but they thought he was too old.”

Roland felt relieved. If this Petheram was an old man he did not so much object to her enthusiasm. He conjured up a picture of a white-haired elder with a fatherly manner.

“Oh, he’s old, is he?”

“Twenty-four.”

There was a brief silence. Something in the girl’s expression stung Roland. She wore a rapt look, as if she were dreaming of the absent Petheram—confound him! He would show her that Petheram was not the only man worth looking rapt about. He rose.

“Would you mind giving me your address?” he said.

“Why?”

“So that I can communicate with you.”

“Why?”

She spoke quietly, but there was an unpleasant sub-tinkle in her voice, as of one who had a short way with Men Who Communicated with Girls.

“In order,” said Roland, carefully, “that I may offer you your former employment on Squibs. I am going to buy it.”

After all, your man of dash and enterprise, your Napoleon, does have his moments. Without looking at her, he perceived that he had bowled her over completely. Something told him that she was staring at him open-mouthed.

Meanwhile, a voice within him was muttering anxiously, “I wonder how much this is going to cost?”

“You’re going to buy Squibs!”

Her voice had fallen away to an awe-struck whisper.

“I am.”

She gulped.

“Well, I think you’re wonderful.”

So did Roland.

“Where will a letter find you?” he asked.

“My name is March—Bessie March. I’m living at twenty-seven, Guilford Street.”

“Twenty-seven. Thank you. Good morning. I will communicate with you in due course.”

He raised his hat and walked away. He had only gone a few steps when there was a patter of feet behind him. He turned.

“I—I just wanted to thank you,” she said.

“Not at all,” said Roland. “Not at all.”

He went on his way tingling with just triumph. Petheram? Who was Petheram? Who, in the name of goodness, was Petheram? He had put Petheram in his proper place, he rather fancied. Petheram, forsooth. Laughable!

A copy of the current number of Squibs, purchased at a bookstall, informed him that the offices of the paper were in Fetter Lane. It was evidence of his exalted state of mind that he proceeded thither in a cab.

There might have been space to swing a cat in the editorial sanctum of Squibs, but it would have been a near thing. As for the outer office, in which a vacant-faced lad of fifteen received Roland and instructed him to wait while he took his card in to Mr. Petheram, it was a mere box. Roland was afraid to expand his chest for fear of bruising it.

The boy returned to say that Mr. Petheram would see him.

Mr. Petheram was a young man with a mop of hair, spectacles, and an air of almost painful restraint, as if it were only by willpower of a high order that he kept himself from bounding about like a Dervish. He was in his shirt-sleeves, and the table before him was heaped high with papers. Opposite him, evidently in the act of taking his leave, was a comfortable-looking man of middle age, with a red face and a short beard. He left as Roland entered, and Roland was surprised to see Mr. Petheram spring to his feet, shake his fist at the closing door, and kick the wall with a vehemence which brought down several inches of discoloured plaster.

“Take a seat,” he said, when he had finished this performance. “What can I do for you?”

Roland had always imagined that editors in their private offices were less easily approached, and, when approached, more brusque. The fact was that Mr. Petheram, whose optimism nothing could quench, had mistaken him for a prospective advertiser.

“I want to buy the paper,” said Roland. He was aware that this was an abrupt way of approaching the subject, but, after all, he did want to buy the paper, so why not say so?

Mr. Petheram fizzed in his chair. He glowed with excitement.

“Do you mean to tell me there’s a single bookstall in London which has sold out? Great Scot! perhaps they’ve all sold out! How many did you try?”

“I mean buy the whole paper. Become proprietor, you know.”

Roland felt that he was blushing, and hated himself for it. He ought to be carrying this thing through with an air.

Mr. Petheram looked at him blankly.

“Why?” he asked.

“Oh, I don’t know,” said Roland. He felt the interview was going all wrong. It lacked a stateliness which this kind of interview should have had.

“Honestly?” said Mr. Petheram. “You aren’t pulling my leg?”

Roland nodded. Mr. Petheram appeared to struggle with his conscience, and finally to be worsted by it, for his next remarks were limpidly honest.

“Don’t you be an ass,” he said. “You don’t know what you’re letting yourself in for. Did you see that blighter who went out just now? Did you ever see a man in such a beastly state of robust health? Do you know who he is? That’s the fellow we’ve got to pay five pounds a week to for life.”

“Why?”

“We can’t get rid of him. When the paper started, the proprietors—not the present ones—thought it would give the thing a boom if they had a football competition with a first prize of a fiver a week for life. Well, that’s the man who won it. He’s been handed down as a legacy from proprietor to proprietor, till now we’ve got him. Ages ago they tried to get him to compromise for a lump sum down, but he wouldn’t. Said he would only spend it, and preferred to get it by the week. Well, by the time we’ve paid that vampire, there isn’t much left out of our profits. That’s why we are at present a little understaffed.”

A frown clouded Mr. Petheram’s brow. Roland wondered if he was thinking of Bessie March.

“I know all about that,” he said.

“And you still want to buy the thing?”

“Yes.”

“But what on earth for? Mind you, I ought not to be crabbing my own paper, but you seem a good chap, and I don’t want to see you landed. Why are you doing it?”

“Oh, just for fun.”

“Ah, now you’re talking. If you can afford expensive amusements, go ahead.”

He put his feet on the table and lit a short pipe. His gloomy views on the subject of Squibs gave way to a wave of optimism.

“You know,” he said, “there’s really a lot of life in the old rag yet, if it were properly run. What has hampered us has been lack of capital. We haven’t been able to advertise. I’m bursting with ideas for booming the paper, only naturally you can’t do it for nothing. As for editing, what I don’t know about editing—but perhaps you had got somebody else in your mind?”

“No, no,” said Roland, who would not have known an editor from an office-boy. The thought of interviewing prospective editors appalled him.

“Very well, then,” resumed Mr. Petheram, reassured, kicking over a heap of papers to give more room for his feet. “Take it that I continue as editor. We can discuss terms later. Under the present régime I have been doing all the work in exchange for a happy home. I suppose you won’t want to spoil the ship for a ha’porth of tar? In other words, you would sooner have a happy, well-fed editor running about the place than a broken-down wreck who might swoon from starvation?”

“But one moment,” said Roland. “Are you sure that the present proprietors will want to sell?”

“Want to sell!” cried Mr. Petheram, enthusiastically. “Why, if they know you want to buy you’ve as much chance of getting away from them without the paper as—as—well, I can’t think of anything that has such a poor chance of anything. If you aren’t quick on your feet, they’ll cry on your shoulder. Come along, and we’ll round them up now.”

He struggled into his coat and gave his hair an impatient brush with a notebook.

“There’s just one other thing,” said Roland. “I have been a regular reader of Squibs for some time, and I particularly admire the way in which the Woman’s Page——”

“You mean you want to re-engage the editress? Rather. You couldn’t do better. I was going to suggest it myself. Now, come along quick before you change your mind or wake up.”

Within a very few days of becoming sole proprietor of Squibs Roland began to feel much as a man might who, a novice at the art of steering cars, should find himself at the wheel of a runaway motor. Young Mr. Petheram had spoken nothing less than the truth when he had said that he was full of ideas for booming the paper. The infusion of capital into the business acted on him like a powerful stimulant. He exuded ideas at every pore.

Roland’s first notion had been to engage a staff of contributors. He was under the impression that contributors were the lifeblood of a weekly journal. Mr. Petheram corrected this view. He consented to the purchase of a lurid serial story, but that was the last concession he made. Nobody could accuse Mr. Petheram of lack of energy. He was willing, even anxious, to write the whole paper himself, with the exception of the Woman’s Page, now brightly conducted once more by Miss March. What he wanted Roland to concentrate himself upon was the supplying of capital for ingenious advertising schemes.

“How would it be,” he asked one morning (he always began his remarks with “How would it be?”), “if we paid a man to walk down Piccadilly in white skin-tights with the word ‘Squibs’ painted in red letters across his chest?”

Roland thought it would certainly not be.

“Good, sound advertising stunt,” urged Mr. Petheram. “You don’t like it? All right. You’re the boss. Well, how would it be to have a squad of men dressed as Zulus with white shields bearing the legend ‘Squibs’? See what I mean? Have them sprinting along the Strand shouting ‘Wah, wah, wah! Buy it! Buy it!’ It would make people talk.”

Roland emerged from these interviews with his skin crawling with modest apprehension. His was a retiring nature, and the thought of Zulus sprinting down the Strand shouting “Wah, wah, wah! Buy it! Buy it!” with reference to his personal property appalled him.

He was beginning now heartily to regret having bought the paper, as he generally regretted every definite step which he took. The glow of romance which had sustained him during the preliminary negotiations had faded entirely. A girl has to be possessed of unusual charm to continue to captivate B. when she makes it plain daily that her heart is the exclusive property of A.; and Roland had long since ceased to cherish any delusion that Bessie March was ever likely to feel anything but a mild liking for him. Young Mr. Petheram had obviously staked out an indisputable claim. Her attitude towards him was that of an affectionate devotee towards a high priest. One morning, entering the office unexpectedly, Roland found her kissing the top of Mr. Petheram’s head; and from that moment his interest in the fortunes of Squibs sank to zero. It amazed him that he could ever have been idiot enough to have allowed himself to be entangled in this insane venture for the sake of an insignificant-looking bit of a girl with a snub nose and a poor complexion.

What particularly galled him was the fact that he was throwing away good cash for nothing. It was true that his capital was more than equal to the on-the-whole modest demands of the paper, but that did not alter the fact that he was wasting money. Mr. Petheram always talked buoyantly about turning the corner, but the corner always seemed just as far off.

The old idea of flight, to which he invariably had recourse in any crisis, came upon Roland with irresistible force. He packed a bag, and went to Paris. There, in the discomforts of life in a foreign country, he contrived for a month to forget his white elephant.

He returned by the evening train which deposits the traveller in London in time for dinner.

Strangely enough, nothing was farther from Roland’s mind than his bright weekly paper, as he sat down to dine in a crowded grill-room near Piccadilly Circus. Four weeks of acute torment in a city where nobody seemed to understand the simplest English sentence had driven Squibs completely from his mind.

The fact that such a paper existed was brought home to him with the coffee. A note was placed upon his table by the attentive waiter.

“What’s this?” he asked.

“The lady, sare,” said the waiter, vaguely.

Roland looked round the room excitedly. The spirit of romance gripped him. There were many ladies present, for this particular restaurant was a favourite with artistes who were permitted to “book in” at their theatres as late as eight-thirty. None of them looked particularly self-conscious, yet one of them had sent him this quite unsolicited tribute. He tore open the envelope.

The message, written in a flowing feminine hand, was brief, and Mrs. Grundy herself could have taken no exception to it.

“Squibs, one penny weekly, buy it,” it ran.

All the mellowing effects of a good dinner passed away from Roland. He was feverishly irritated. He paid his bill, and left the place.

A visit to a neighbouring music-hall occurred to him as a suitable sedative. Hardly had his nerves ceased to quiver sufficiently to allow him to begin to enjoy the performance, when, in the interval between two of the turns, a man rose in one of the side boxes.

“Is there a doctor in the house?”

There was a hush in the audience. All eyes were directed towards the box. A man in the stalls rose, blushing, and cleared his throat.

“My wife has fainted,” continued the speaker. “She has just discovered that she has lost her copy of Squibs.”

The audience received the statement with the bovine stolidity of an English audience in the presence of the unusual. Not so Roland. Even as the purposeful-looking chuckers-out wended their leopard-like steps towards the box, he was rushing out into the street.

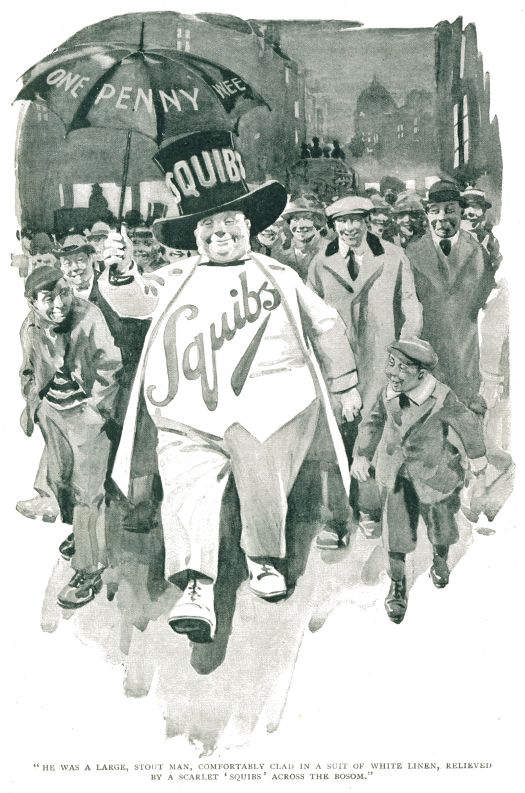

As he stood cooling his indignation in the pleasant breeze which had sprung up, he was aware of a dense crowd proceeding towards him. It was headed by an individual who shone out against the drab background like a good deed in a naughty world. Nature hath framed strange fellows in her time, and this was one of the strangest that Roland’s bulging eyes had ever rested upon. He was a large, stout man, comfortably clad in a suit of white linen, relieved by a scarlet “Squibs” across the bosom. His top-hat, at least four sizes larger than any top-hat worn out of a pantomime, flaunted the same word in letters of flame. His umbrella, which, though the weather was fine, he carried open above his head, bore the device, “One Penny Weekly.”

The arrest of this person by a vigilant policeman and Roland’s dive into a taxi-cab occurred simultaneously. Roland was blushing all over. His head was in a whirl. He took the evening paper handed in through the window of the cab quite mechanically, and it was only the strong exhortations of the vender which eventually induced him to pay for it. This he did with a sovereign, and the cab drove off.

He was just thinking of going to bed several hours later, when it occurred to him that he had not read his paper. He glanced at the first page. The middle column was devoted to a really capitally written account of the proceedings at Bow Street consequent upon the arrest of six men who, it was alleged, had caused a crowd to collect to the disturbance of the peace by parading the Strand in the undress of Zulu warriors, shouting in unison the words, “Wah, wah, wah! Buy Squibs!”

Young Mr. Petheram greeted Roland with a joyous enthusiasm which the hound Argus, on the return of Ulysses, might have equalled but could scarcely have surpassed. It seemed to be Mr. Petheram’s considered opinion that God was in His Heaven and all right with the world. Roland’s attempts to correct this belief fell on deaf ears.

“Have I seen the advertisements?” he cried, echoing his editor’s first question. “I’ve seen nothing else.”

“There!” said Mr. Petheram, proudly.

“It can’t go on.”

“Yes, it can. Don’t you worry. I know they’re arrested as fast as we send them out, but, bless you, the supply’s endless. Ever since the revue boom started and actors were expected to do six different parts in seven minutes, there are platoons of music-hall pros hanging about the Strand, ready to take on any sort of job you offer them. I have a special staff flushing the Bodegas. These fellows love it. It’s meat and drink to them to be right in the public eye like that. Makes them feel ten years younger. It’s wonderful the talent kicking about. Those Zulus used to have a steady job as the Six Brothers Biff, Society Contortionists. The revue craze killed them professionally. They cried like children when we took them on. By the way, could you put through an expenses cheque before you go? The fines mount up a bit. But don’t you worry about that, either. We’re coining money. I’ll show you the returns in a minute. I told you we should turn the corner. Turned it! Damme, we’ve whizzed round it on two wheels. Have you had time to see the paper since you got back? No? Then you haven’t seen our new Scandal Page—‘We Just Want to Know, You Know.’ It’s a corker, and it’s sent the circulation up like a rocket. Everybody reads Squibs now. I was hoping you would come back soon. I wanted to ask you about taking new offices. We’re a bit above this sort of thing now.”

Roland, meanwhile, was reading with horrified eyes the alleged corking scandal page. It seemed to him, without exception, the most frightful production he had ever seen. It appalled him.

“This is awful!” he moaned. “We shall have a hundred libel actions.”

“Oh, no, that’s all right. It’s all fake stuff, though the public doesn’t know it. If you stuck to real scandals you wouldn’t get a par a week. A more moral set of blameless wasters than the blighters who constitute modern society you never struck. But it reads all right, doesn’t it? Of course, every now and then one does hear something genuine, and then it goes in. For instance, have you heard of Percy Pook, the bookie? I have got a real ripe thing in about Percy this week—the absolute limpid truth. It will make him sit up a bit. There, just under your thumb.”

Roland removed his thumb, and, having read the paragraph in question, started as if he had removed it from a snake. “But this is bound to mean a libel action!” he cried.

“Not a bit of it,” said Mr. Petheram, comfortably. “You don’t know Percy. I won’t bore you with his life-history, but take it from me he doesn’t rush into a court of law from sheer love of it. You’re safe enough.”

But it appeared that Mr. Pook, though coy in the matter of cleansing his scutcheon before a judge and jury, was not wholly without weapons of defence and offence. Arriving at the office next day, Roland found a scene of desolation, in the middle of which sat Jimmy, the vacant-faced office-boy.

“He’s gorn,” he observed, looking up as Roland entered.

“What do you mean?”

“Mr. Petheram. A couple of fellers come in and went through, and there was a uproar inside there, and presently out they come running, and I went in, and there was Mr. Petheram on the floor knocked silly, and the furniture all broke, and now ’e’s gorn to ’orspital. Those fellers ’ad been putting ’im froo it proper,” concluded Jimmy, with moody relish.

Roland sat down weakly. Silence reigned in the offices of Squibs.

It was broken by the arrival of Miss March. Her exclamation of astonishment at the sight of the wrecked room led to a repetition of Jimmy’s story.

She vanished on hearing the name of the hospital to which the stricken editor had been removed, and returned an hour later with flashing eyes and a set jaw.

“Aubrey,” she said—it was news to Roland that Mr. Petheram’s name was Aubrey—“is very much knocked about, but he is conscious and sitting up and taking nourishment.”

“That’s good.”

“In a spoon only.”

“Ah!” said Roland.

“The doctor says he will not be out for a week. Aubrey is certain it was that horrible bookmaker’s men who did it, but of course he can prove nothing. But his last words to me were, ‘Slip it into Percy again this week.’ He has given me one or two things to mention. I don’t understand them, but Aubrey says they will make him wild.”

Roland’s flesh crept. The idea of making Mr. Pook any wilder than he appeared to be at present horrified him. Panic gave him strength, and he addressed Miss March, who was looking more like a modern Joan of Arc than anything else on earth, firmly.

“Miss March,” he said, “I realize that this is a crisis, and that we must all do all that we can for the paper, and I am ready to do anything in reason—but I will not slip it into Percy. You have seen the effects of slipping it into Percy. What he or his minions will do if we repeat the process I do not care to think.”

“You are afraid?”

“Yes,” said Roland, simply.

Miss March turned on her heel. It was plain that she regarded him as a worm. Roland did not like being regarded as a worm, but it was infinitely better than being regarded as an interesting case by the house-surgeon of a hospital. He belonged to the school of thought which holds that it is better that people should say of you, “There he goes,” than that they should say, “How peaceful he looks.”

Thanks to Mr. Petheram, there was a sufficient supply of material in hand to enable Squibs to run a fortnight on its own momentum. Roland, however, did not know this, and with a view to doing what little he could to help, he informed Miss March that he would write the Scandal Page. It must be added that the offer was due quite as much to prudence as to chivalry. Roland simply did not dare to trust her with the Scandal Page. In her present mood it was not safe. To slip it into Percy would, he felt, be with her the work of a moment.

Literary composition had never been Roland’s forte. He stared at the white paper and chewed the pencil which should have been marring its whiteness with stinging paragraphs. No sort of idea came to him.

His brow grew damp. What sort of people—except bookmakers—did things you could write scandal about? As far as he could ascertain, nobody.

He picked up the morning paper. The name Windleband caught his eye. A kind of pleasant melancholy came over him as he read the paragraph. How long ago it seemed since he had met that genial financier. The paragraph was not particularly interesting. It gave a brief account of some large deal which Mr. Windleband was negotiating. Roland did not understand a word of it, but it gave him an idea.

Mr. Windleband’s financial standing, he knew, was above suspicion. Mr. Windleband had made that clear to him during his visit. There could be no possibility of offending Mr. Windleband by a paragraph or two about the manners and customs of financiers. Phrases which his kindly host had used during his visit came back to him, and with them inspiration. Within five minutes he had compiled the following:—

We Just Want to Know, you Know.

Who is the eminent financier at present engaged upon one of his biggest deals?

Whether the public would not be well advised to look a little closer into it before investing their money?

If it is not a fact that this gentleman has bought a first-class ticket to the Argentine in case of accidents?

Whether he may not have to use it at any moment?

After that it was easy. Ideas came with a rush. By the end of an hour he had completed a Scandal Page of which Mr. Petheram himself might have been proud, without a suggestion of slipping it into Percy. He felt that he could go to Mr. Pook and say, “Percy, on your honour as a British bookmaker, have I slipped it into you in any way whatsoever?” And Mr. Pook would be compelled to reply, “You have not.”

Miss March read the proofs of the page and sniffed. But Miss March’s blood was up, and she would have sniffed at anything not directly hostile to Mr. Pook.

A week later Roland sat in the office of Squibs, reading a letter. It had been sent from No. 18A, Bream’s Buildings, E.C., but, from Roland’s point of view, it might have come direct from Heaven; for its contents, signed by Harrison, Harrison, Harrison, and Harrison, solicitors, were to the effect that a client of theirs had instructed them to approach him with a view to purchasing the paper. He would not find their client disposed to haggle over terms, so, hoped Messrs. Harrison, Harrison, Harrison, and Harrison, in the event of Roland being willing to sell, they could speedily bring matters to a satisfactory conclusion.

Any conclusion which had left him free of Squibs without actual pecuniary loss would have been satisfactory to Roland. He had conceived a loathing for his property which not even its steadily-increasing sales could mitigate. He was round at Messrs. Harrisons’ offices as soon as a taxi could take him there.

The lawyers were for spinning the thing out with guarded remarks and cautious preambles, but Roland’s methods of doing business were always rapid.

“This chap,” he said, “this fellow who wants to buy Squibs, what’ll he give?”

“That,” began one of the Harrisons, ponderously, “would, of course, largely depend——”

“I’ll take five thousand. Lock, stock, and barrel, including the present staff, an even five thousand. How’s that?”

“Five thousand is a large——”

“Take it or leave it.”

“My dear sir, you hold a pistol to our heads. However, I think that our client might consent to the sum you mention.”

“Good. Well, directly I get his cheque the thing’s his. By the way, who is your client?”

Mr. Harrison coughed. “His name,” he said, “will be familiar to you. He is the eminent financier, Mr. Dermot Windleband.”

[Next month: “The Episode of the Exiled Monarch.”]

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums