Vanity Fair, June 1916

A NEW FIGURE IN MUSICAL COMEDY

The Discovery of a Hitherto Neglected Factor in the Producing World

By C. P. West

IT is a cheering thing to reflect how greatly musical comedy has improved of recent years. The curtain no longer rises on the exterior of the Royal Hunting Lodge, nor is a placidly digesting audience compelled to imperil the smooth action of its digestive apparatus by following the ramifications of a story which begins with the heroine changing clothes with her maid and the hero changing clothes with his valet and all the other characters assuming disguises in order to test the sincerity of somebody’s love. Our leading ladies have cured themselves of their deep-rooted habit of pausing at a crisis of their affairs to sing “My Honolulu Queen,” with chorus of Esquimaux and Japanese maidens. The naval lieutenant, once the premier pest of this form of entertainment, has practically ceased to exist; and Hans Dillpickleheiffer, the Milwaukee brewer who is mistaken for the missing prince, has passed away. To-day it is the pieces of the “Very Good Eddie” type that play to capacity.

But even now there is room for improvement—yea, even now, when comedians talk English instead of diluted Dutch and the moon is seldom permitted to flood the stage in the middle of the afternoon reception at the Duchess’s.

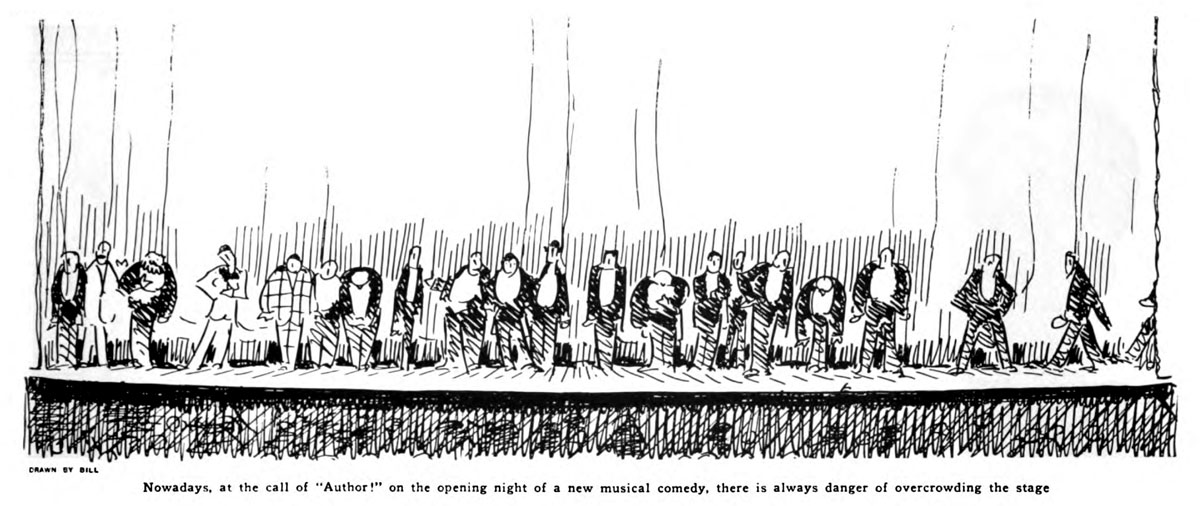

NO one who has attended the opening performance of a musical comedy can have failed to be struck by a singular omission from the procession which emerges from the wings to bow in response to the call of “Author.” At first sight, perhaps it might seem that everybody responsible for the success of the entertainment is there. The aggregation contains the author, the part-author, the assistant-collaborator, the man who wrote in additional scenes, the man who contributed extra lines, the man who suggested supplementary business, the man who evolved the central idea, the lyrist, the associate-lyrists, the composer, the man who added extra numbers, the man who contributed supplementary music, the producer, the assistant-producer, the assistant-producer’s assistant, the man who helped the assistant-producer’s assistant assist the assistant-producer assist the producer to produce, the manager, the manager’s colleagues, the wardrobe-mistress, the box-office man, the fireman, the stage-manager, the stage-manager’s assistant, the stage-door keeper, and the call-boy. All these are present. Who then, is missing? One who has done yeoman service to the production—the man who drew up the programme. He alone takes no call. Why?

WHEN one considers what a large part of the evening in these days of lengthy intermissions, is occupied by the audience in looking at their programmes, one gets some idea of the responsibility that rests on this man’s shoulders. He has got to achieve the object of every author—the combining of instruction with entertainment. He has got to be snappy and interesting and still confine himself to severe facts. It is not easy for him to resist the temptation to achieve a sensational surprise by writing:

“Sambo—(a negro servant)—Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree.” He knows he could excite interest and dramatic suspense by doing it, but he is too much of an artist to descend to such flashy and catchpenny literary methods. He wants to grip his public, but not at the expense of accuracy.

Have you ever paused to consider the amount of work the author of a musical comedy programme puts into his task? And, not content with being painstaking, he seldom fails to soar into vers libre of an extremely high order. Take this, for example, from a recent effort. Like most similar flights, it occurs in the chapter entitled “Personnel of the Chorus.” This is where the programme writer always lets himself go:

“Edythe Trevelyan, Mae de Vere, Ethyl Magink, Babs Byng, Genevieve Terwilliger, Sue Ricketts, Loo Ricketts, Marianne Aida Breamworthy, Birdie Bootle, Gypsy Tootle, Dorothie Wootle, Lotta Pepp.”

Of course, to get the full effect—the real majestic sweep of the thing—you want to hear it recited to music, but even in print, doesn’t it grip you? Doesn’t it stir your blood like some grand marching song?

MENTION of the personnel of the chorus brings us to what is perhaps the most-needed reform of all in the musical comedy world. For a long time now sporting editors have been pleading with football authorities of the large colleges to number their players in order to facilitate recognition on the field of play. Under the present system of non-identification, they argue, it is impossible for the public to distinguish individuals in the mêlée. The movement has our hearty support, but to our mind the institution of numbers is needed far more on the musical stage than on the football field. After all, it means little in our young lives whether it was Jack Slugger of Yale, or his comrade Dick Biff, who enabled the ball to be advanced six inches by rendering the opposing full-back a cripple for life; and in any case we shall be about to find out all about it from the papers next day. But as to the chorus it is altogether different.

A young man goes, full of optimism and mixed drinks, to see a musical comedy. Within the first five minutes, he has decided life will be a dreary desert for him unless he is permitted to escort to supper at the Follies Roof the dazzling creature three from the end of the first row counting from the left—just over the French horn. How is he to ascertain which she is? It is a problem of nightly occurrence, and it still awaits a solution. The tragedy of Romeo and Juliet itself was not more poignant, for they did manage to introduce themselves. Our hero scans his programme, but it gives him no clue.

FINALLY, in desperation, being compelled to make a choice, he stakes his all on the girl being Birdie Bootle, and sends round a carefully worded note to the owner of that name. Only when it is too late does he discover that Birdie Bootle is the unpleasant-looking girl in the back row and that the one he wanted was Dorothie Wootle. A few mistakes of this nature discourage him to the extent of staying at home at night and reading the Encyclopaedia Britannica. The adoption of the number system would render such tragedies impossible.