HROUGH the

curtained windows of the furnished apartment which Mrs. Horace Hignett had

rented for her stay in New York, rays of golden sunlight peeped in like the

foremost spies of some advancing army. It was a fine summer morning. The

hands of the Dutch clock in the hall pointed to thirteen minutes past nine;

those of the ormolu clock in the sitting-room to eleven minutes past ten;

those of the carriage clock on the bookshelf to fourteen minutes to six. In

other words it was exactly eight; and Mrs. Hignett acknowledged the fact by

moving her head on the pillow, opening her eyes, and sitting up in bed. She

always woke at eight precisely.

HROUGH the

curtained windows of the furnished apartment which Mrs. Horace Hignett had

rented for her stay in New York, rays of golden sunlight peeped in like the

foremost spies of some advancing army. It was a fine summer morning. The

hands of the Dutch clock in the hall pointed to thirteen minutes past nine;

those of the ormolu clock in the sitting-room to eleven minutes past ten;

those of the carriage clock on the bookshelf to fourteen minutes to six. In

other words it was exactly eight; and Mrs. Hignett acknowledged the fact by

moving her head on the pillow, opening her eyes, and sitting up in bed. She

always woke at eight precisely.

Was this Mrs. Hignett, the Mrs. Hignett, the world-famous writer on theosophy, the noted author of “The Spreading Light,” “What of the Morrow,” and all the rest of that well-known series? I’m glad you asked me. Yes, she was. She had come over to America on a lecturing tour.

The year 1920, it will be remembered, was a trying one for the inhabitants of the United States. Every boat that arrived from England brought a fresh swarm of British lecturers to the country. Novelists, poets, scientists, philosophers, and plain, ordinary bores; some herd instinct seemed to affect them all simultaneously. It was like one of those great race movements of the Middle Ages. Men and women of widely differing views on religion, art, politics, and almost every other subject: on this one point the intellectuals of Great Britain were single-minded—that there was easy money to be picked up on the lecture platforms of America, and that they might just as well grab it as the next person.

Mrs. Hignett had come over with the first batch of immigrants; for, spiritual as her writings were, there was a solid streak of business sense in this woman, and she meant to get hers while the getting was good. She was half way across the Atlantic with a complete itinerary booked before ninety per cent of the poets and philosophers had finished sorting out their clean collars and getting their photographs taken for the passport.

She had not left England without a pang, for departure had involved sacrifices. More than anything else in the world she loved her charming home, Windles, in the county of Hampshire, for so many years the seat of the Hignett family. Windles was as the breath of life to her. Its shady walks, its silver lake, its noble elms, the old gray stone of its walls—these were bound up with her very being. She felt that she belonged to Windles, and Windles to her. Unfortunately, as a matter of cold, legal accuracy, it did not. She did but hold it in trust for her son, Eustace, until such time as he should marry and take possession of it himself. There were times when the thought of Eustace marrying and bringing a strange woman to Windles chilled Mrs. Hignett to her very marrow. Happily, her firm policy of keeping her son permanently under her eye at home, and never permitting him to have speech with a female below the age of fifty, had averted the peril up till now.

Eustace had accompanied his mother to America. It was his faint snores which she could hear in the adjoining room, as, having bathed and dressed, she went down the hall to where breakfast awaited her. She smiled tolerantly. She had never desired to convert her son to her own early rising habits, for, apart from not allowing him to call his soul his own, she was an indulgent mother. Eustace would get up at half-past nine, long after she had finished breakfast, read her mail, and started her duties for the day.

Breakfast was on the table in the sitting-room, a modest meal of rolls, cereal, and imitation coffee. Beside the pot containing this hell-brew was a little pile of letters. Mrs. Hignett opened them as she ate. Among them there was a letter from her brother Mallaby—Sir Mallaby Marlowe, the eminent London lawyer—saying that his son Sam, of whom she had never approved, would be in New York shortly, passing through on his way back to England, and hoping that she would see something of him.

She had just risen from the table when there was a sound of voices in the hall, and presently the domestic staff, a gaunt Irish lady of advanced years, entered the room.

“Ma’am, there was a gentleman.”

Mrs. Hignett was annoyed. Her mornings were sacred.

“Didn’t you tell him I was not to be disturbed?”

“I did not. I loosed him into the parlor.” The staff remained for a moment in melancholy silence, then resumed. “He says he’s your nephew. His name’s Marlowe.”

Mrs. Hignett experienced no diminution of her annoyance. She had not seen her nephew Sam for ten years and would have been willing to extend the period. She remembered him as an untidy small boy who, once or twice, during his school holidays, had disturbed the cloistral peace of Windles with his beastly presence. However, blood being thicker than water, and all that sort of thing, she supposed she would have to give him five minutes. She went into the sitting-room and found there a young man who looked more or less like all other young men, though perhaps rather fitter than most.

“Hallo, Aunt Adeline!” he said awkwardly.

“Well, Samuel!” said Mrs. Hignett.

There was a pause. Mrs. Hignett, who was not fond of young men and disliked having her mornings broken into, was thinking that he had not improved in the slightest degree since their last meeting; and Sam, who imagined that he had long since grown to man’s estate and put off childish things, was embarrassed to discover that his aunt still affected him as of old. That is to say, she made him feel as if he had omitted to shave, and, in addition to that, had swallowed some drug which had caused him to swell unpleasantly, particularly about the hands and feet.

“Jolly morning,” said Sam perseveringly.

“So I imagine. I have not yet been out.”

“Thought I’d look in and see how you were.”

“That was very kind of you. The morning is my busy time, but . . . yes, that was very kind of you!”

There was another pause.

“How do you like America?” said Sam.

“I dislike it exceedingly.”

“Yes? Well, of course some people do. I like it myself,” said Sam. “I’ve had a wonderful time. Everybody’s treated me like a rich uncle. I’ve been in Detroit, you know, and they practically gave me the city, and asked me if I’d like another to take home in my pocket. Never saw anything like it! I might have been the missing heir! I think America’s the greatest invention on record.”

“And what brought you to America?” said Mrs. Hignett, unmoved by this rhapsody.

“Oh, I came over to play golf. In a tournament, you know.”

“Surely at your age,” said Mrs. Hignett disapprovingly, “you could be better occupied. Do you spend your whole time playing golf?”

“Oh no! I hunt a bit and shoot a bit, and I swim a good lot, and I still play football occasionally.”

“I wonder your father does not insist on your doing some useful work.”

“He is beginning to harp on the subject rather. I suppose I shall take a stab at it sooner or later. Father says I ought to get married, too.”

“He is perfectly right.”

“I suppose old Eustace will be getting hitched up one of these days?” said Sam.

Mrs. Hignett started violently. “What makes you say that?”

“Oh, well, he’s a romantic sort of fellow. Writes poetry and all that.”

“There is no likelihood at all of Eustace marrying. He is of a shy and retiring temperament and sees few women. He is almost a recluse.”

Sam was aware of this, and had frequently regretted it. He had always been fond of his cousin in that half-amused and rather patronizing way in which men of thews and sinews are fond of the weaker brethren who run more to pallor and intellect; and he had always felt that if Eustace had not had to retire to Windles to spend his life with a woman whom, from his earliest years, he had always considered the Empress of the Wash-outs, much might have been made of him. Both at school and at Oxford, Eustace had been—if not a sport—at least a decidedly cheery old bean. Sam remembered Eustace at school breaking glass globes with a slipper in a positively rollicking manner. He remembered him at Oxford playing up to him manfully at the piano on the occasion when he had done that imitation of Frank Tinney which had been such a hit at the Trinity smoker. Yes, Eustace had had the makings of a pretty sound egg, and it was too bad that he had allowed his mother to coop him up down in the country miles away from anywhere.

“Eustace is returning to England on Saturday,” said Mrs. Hignett. She spoke a little wistfully. She had not been parted from her son since he had come down from Oxford; and she would have liked to keep him with her till the end of her lecturing tour. That, however, was out of the question. It was imperative that, while she was away, he should be at Windles. Nothing would have induced her to leave the place at the mercy of servants who might trample over the flower beds, scratch the polished floors, and forget to cover up the canary at night. “He sails on the ‘Atlantic’.”

“That’s splendid,” said Sam. “I’m sailing on the ‘Atlantic’ myself. I’ll go down to the office and see if we can’t have a stateroom together. But where is he going to live when he gets to England?”

“Where is he going to live? Why, at Windles, of course. Where else?”

“But I thought you were letting Windles for the summer?”

Mrs. Hignett stared.

“Letting Windles!” She spoke as one might address a lunatic. “What put that extraordinary idea into your head?”

It seemed to Sam that his aunt spoke somewhat vehemently, even snappishly, in correcting what was a perfectly natural mistake. He could not know that the subject of letting Windles for the summer was one which had long since begun to infuriate Mrs. Hignett. People had certainly asked her to let Windles. In fact, people had pestered her. There was a rich fat man, an American named Bennett, whom she had met, just before sailing, at her brother’s house in London. Invited down to Windles for the day, Mr. Bennett had fallen in love with the place and had begged her to name her own price. Not content with this, he had pursued her with his pleadings by means of wireless telegraph while she was on the ocean, and had not given up the struggle even when she reached New York. She had not been in America two days when there had arrived a Mr. Mortimer, bosom friend of Mr. Bennett, carrying on the matter where the other had left off. For a whole week Mr. Mortimer had tried to induce her to reconsider her decision, and had only stopped because he had had to leave for England himself to join his friend.

“Nothing will induce me ever to let Windles,” she said with finality, and rose significantly. Sam, perceiving that the audience was at an end—and glad of it—also got up.

“Well, I think I’ll be going down and seeing about that stateroom,” he said.

“Certainly. I am a little busy just now, preparing notes for my next lecture.”

“Of course, yes. Mustn’t interrupt you. I suppose you’re having a great time, gassing away—I mean—Well, good-by!”

“Good-by!”

Mrs. Hignett, frowning, had hardly succeeded in concentrating herself, when the door opened to admit the daughter of Erin once more.

“Ma’am, there was a gentleman.”

“This is intolerable!” cried Mrs. Hignett. “Is he a reporter from one of the newspapers?”

“He is not. He has spats and a tall-shaped hat. His name is Bream Mortimer.”

Mrs. Hignett went into the dining-room in a state of cold fury, determined to squash the Mortimer family, once and for all.

“Good morning, Mr. Mortimer.”

Bream Mortimer was tall and thin. He had small bright eyes and a sharply curving nose. He looked much more like a parrot than most parrots do. It gave strangers a momentary shock of surprise when they saw Bream Mortimer in restaurants eating roast beef. They had the feeling that he would have preferred sunflower seeds.

“Morning, Mrs. Hignett,” said Bream Mortimer.

“Please sit down.”

Bream Mortimer sat down. He looked as though he would rather have hopped onto a perch, but he sat down. He glanced about the room with gleaming, excited eyes.

“Mrs. Hignett, I must have a word with you alone!”

“You are having a word with me alone.”

“I hardly know how to begin.”

“Then let me help you. It is quite impossible. I will never consent.”

Bream Mortimer started.

“Then you have heard!”

“I have heard about nothing else since I met Mr. Bennett in London. Mr. Bennett talked about nothing else. Your father talked about nothing else. And now,” cried Mrs. Hignett fiercely, “you come and try to reopen the subject. Once and for all, nothing will alter my decision. No money will induce me to let my house.”

“But I didn’t come about that!”

“Then will you kindly tell me why you have come?”

Bream Mortimer looked embarrassed. He wriggled a little, and moved his arms as if he were trying to flap them.

“You know,” he said, “I’m not a man who butts into other people’s affairs—” He stopped.

“No?” said Mrs. Hignett.

Bream began again.

“I’m not a man who—”

Mrs. Hignett was never a very patient woman.

“Let us take all your negative qualities for granted,” she said curtly. “I have no doubt that there are many things which you do not do. Let us confine ourselves to issues of definite importance. What is it, if you have no objection to concentrating your attention on that for a moment, that you wish to see me about?”

“This marriage.”

“What marriage?”

“Your son’s marriage.”

“My son is not married.”

“No, but he’s going to be. At eleven o’clock this morning at the Little Church Round the Corner!”

Mrs. Hignett stared. Then she spoke coldly:

“Are you mad?”

“Well, I’m not any too well pleased, I’m bound to say,” admitted Mr. Mortimer. “You see, darn it all, I’m in love with the girl myself!”

“Who is this girl my misguided son wishes to marry?”

“I don’t know that I’d call him misguided,” said Mr. Mortimer, as one desiring to be fair. “I think he’s a right smart picker! She’s such a corking girl, you know. We were children together and I’ve loved her for years. Ten years at least. But you know how it is—somehow one never seems to get in line for a proposal. I thought I saw an opening in the summer of nineteen-twelve, but it blew over. I’m not one of these smooth, dashing guys, you see, with a great line of talk. I’m not—”

“If you will kindly,” said Mrs. Hignett impatiently, “postpone this essay in psychoanalysis to some future occasion I shall be greatly obliged. I am waiting to hear the name of the girl my son wishes to marry.”

“Haven’t I told you?” said Mr. Mortimer, surprised.

“What is her name?”

“Bennett.”

“Bennett? Wilhelmina Bennett? The daughter of Mr. Rufus Bennett? The red-haired girl I met at lunch one day at your father’s house?”

“That’s it. I think you ought to stop the thing.”

“I intend to. The marriage would be unsuitable in every way. Miss Bennett and my son do not vibrate on the same plane.”

“That’s right. I’ve noticed it myself.”

“I am much obliged to you for coming and telling me of this. I shall take immediate steps.”

“That’s good! But what’s the procedure? How are you going to form a flying wedge and buck center? It’s getting late. She’ll be waiting at the church at eleven. With bells on,” said Mr. Mortimer.

“Eustace will not be there.”

Bream Mortimer hopped down from his chair.

“Well, you’ve taken a weight off my mind. I feel I can rely on you. So I’ll say good-by.”

“Good-by.”

“I mean really good-by. I’m sailing for England on Saturday on the ‘Atlantic’.”

“Indeed? My son will be your fellow traveler.”

Bream Mortimer looked somewhat apprehensive.

“You won’t tell him that I was the one who spilled the beans?”

“I beg your pardon.”

“You won’t tell him that I crabbed his act—gave the thing away—gummed the game?”

“I shall not mention your chivalrous intervention.”

“Chivalrous?” said Bream Mortimer doubtfully. “I don’t know that I’d call it absolutely chivalrous. Of course, all’s fair in love and war. Well, I’m glad you’re going to keep my share in the business under your hat. It might have been awkward meeting him on board.”

“You are not likely to meet Eustace on board. He is a very indifferent sailor, and spends most of his time in his cabin.”

“That’s good! Saves a lot of awkwardness. Well, good-by.”

“Good-by. When you reach England remember me to your father.”

“He won’t have forgotten you,” said Bream Mortimer confidently. He did not see how it was humanly possible for anyone to forget this woman. She was like a celebrated chewing gum. The taste lingered.

Mrs. Hignett was a woman of instant and decisive action. Even while her late visitor was speaking, schemes had begun to form in her mind like bubbles rising to the surface of a rushing river. By the time the door had closed behind Bream Mortimer she had at her disposal no fewer than seven, all good. It took her but a moment to select the best and simplest. She tiptoed softly to her son’s room. Rhythmic snores greeted her listening ears. She opened the door and went noiselessly in.

THE White Star liner ‘Atlantic’ lay at her pier with steam up and gangway down ready for her trip to Southampton. The hour of departure was near, and there was a good deal of mixed activity going on. Men, women, boxes, rugs, dogs, flowers and baskets of fruit were flowing on board in a steady stream.

The usual drove of citizens had come to see the travelers off. There were men on the passenger list who were being seen off by fathers, by mothers, by sisters, by cousins, and by aunts. In the steerage there was an elderly Jewish lady who was being seen off by exactly thirty-seven of her late neighbors in Rivington Street. And two men in the second cabin were being seen off by detectives, surely the crowning compliment a great nation can bestow. The cavernous customs sheds were congested with friends and relatives, and Sam Marlowe, heading for the gangplank, was able to make progress only by employing all the muscle and energy which nature had bestowed upon him, and which, during the twenty-five years of his life, he had developed by athletic exercise. However, after some minutes of silent endeavor, now driving his shoulder into the midriff of some obstructing male, now courteously lifting some stout female off her feet, he had succeeded in struggling to within a few yards of his goal, when suddenly a sharp pain shot through his left arm and he spun round with a cry.

It seemed to Sam that he had been bitten, and this puzzled him, for New York crowds, though they may shove and jostle, rarely bite.

He found himself face to face with an extraordinarily pretty girl.

She was a red-haired girl, with the beautiful ivory skin which goes with red hair. Her eyes, though they were under the shadow of her hat, and he could not be certain, he diagnosed as green, or maybe blue, or possibly gray. Not that it mattered, for he had a catholic taste in feminine eyes. Her figure was trim, and she wore one of those dresses of which a man can say no more than that they look pretty well all right.

Nature abhors a vacuum. Samuel Marlowe was a susceptible young man, and for many a long month his heart had been lying empty, all swept and garnished, with “Welcome” on the mat. This girl seemed to rush in and fill it. She was not the prettiest girl he had ever seen. She was the third prettiest. He had an orderly mind, one capable of classifying and docketing girls. But there was a subtle something about her, a sort of how-shall-one-put-it, which he had never encountered before. He swallowed convulsively. At last, he told himself, he was in love, really in love, and at first sight, too, which made it all the more impressive.

But she had bitten him in the arm. That was hardly the right spirit. That, he felt, constituted an obstacle.

“Oh, I’m so sorry!” she cried.

Well, of course if she regretted her rash act. . . . After all, an impulsive girl might bite a man in the arm in the excitement of the moment, and still have a sweet, womanly nature.

“The crowd seems to make Pinky-Boodles so nervous.”

Sam might have remained mystified; but at this juncture there proceeded from a bundle of rugs in the neighborhood of the girl’s lower ribs a sharp yapping sound, of such a caliber as to be plainly audible over the confused noise of Mamies who were telling Sadies to be sure and write, of Bills who were instructing Dicks to look up old Joe in Paris and give him their best, and of all the fruit boys, candy boys, magazine boys, American flag boys, and telegraph boys who were honking their wares on every side.

“I hope he didn’t hurt you much. You’re the third person he’s bitten to-day.” She kissed the animal in a loving and congratulatory way on the tip of his black nose. “Not counting bell boys, of course,” she added. And then she was swept from him in the crowd, and he was left thinking of all the things he might have said—all those graceful, witty, ingratiating things which just make a bit of difference on these occasions.

He had said nothing. Not a sound, exclusive of the first sharp yowl of pain, had proceeded from him. He had just goggled. A rotten exhibition! Perhaps he would never see this girl again. She looked the sort of girl who comes to see friends off and doesn’t sail herself. And what memory of him would she retain? She would mix him up with the time when she went to visit the deaf-and-dumb hospital.

Sam reached the gangplank, showed his ticket, and made his way through the crowd of passengers, passengers’ friends, stewards, junior officers, and sailors who infested the deck. He proceeded down the main companionway, through a rich smell of indiarubber and mixed pickles, as far as the dining-saloon; then turned down the narrow passage leading to his stateroom.

Staterooms on ocean liners are curious things. When you see them on the chart in the passenger office, with the gentlemanly clerk drawing rings round them in pencil, they seem so vast that you get the impression that, after stowing away all your trunks, you will have room left over to do a bit of entertaining—possibly an informal dance or something. When you go on board you find that the place has shrunk to the dimensions of an undersized cupboard. And then, about the second day out, it suddenly expands again.

Sam, balancing himself on the narrow projecting ledge which the chart in the passenger office had grandiloquently described as a lounge, began to feel the depression which marks the second phase. He almost wished now that he had not been so energetic in having his room changed in order to enjoy the company of his cousin Eustace. It was going to be a tight fit. Eustace’s bag was already in the cabin, and it seemed to take up the entire fairway. Still, after all, Eustace was a good sort, and would be a cheerful companion. And Sam realized that if that girl with the red hair was not a passenger on the boat he was going to have need of diverting society.

A footstep sounded in the passage outside. The door opened.

“Hullo, Eustace!” said Sam.

Eustace Hignett nodded listlessly, sat down on his bag and emitted a deep sigh. He was a small, fragile-looking young man, with a pale, intellectual face. Dark hair fell in a sweep over his forehead.

“Hullo!” he said, in a hollow voice.

Sam regarded him blankly. He had not seen him for some years, but, going by his recollections of him at the university, he had expected something cheerier than this. In fact, he had rather been relying on Eustace to be the life and soul of the party. The man sitting on the bag before him could hardly have filled that rôle at a gathering of Russian novelists.

“What on earth’s the matter?” said Sam.

“The matter?” Eustace Hignett laughed mirthlessly. “Oh, nothing. Nothing much. Nothing to signify. Only, my heart’s broken.” He eyed with considerable malignity the bottle of water in the rack above his head, a harmless object provided by the White Star Company for clients who might desire to clean their teeth during the voyage.

“If you would care to hear the story?” he said.

“Go ahead.”

“Soon after I arrived in America, I met a girl—”

“Talking of girls,” said Marlowe with enthusiasm, “I’ve just seen the only one in the world that really amounts to anything. It was like this: I was shoving my way—”

“Shall I tell you my story, or will you tell me yours?”

“Oh, sorry! Go ahead.”

Eustace Hignett scowled at the printed notice on the wall informing occupants of the stateroom that the name of their steward was J. B. Midgeley.

“She was an extraordinarily pretty girl.”

“So was mine! I give you my honest word I never in all my life saw such—”

“Of course, if you would prefer that I postpone my narrative?” said Eustace coldly.

“Oh, sorry! Carry on. What was her name?”

“Wilhelmina Bennett. She was an extraordinarily pretty girl and highly intelligent. I read her all my poems, and she appreciated them immensely. She enjoyed my singing. My conversation appeared to interest her. She admired my—”

“I see. You made a hit. Now get on with the rest of the story.”

“Don’t bustle me,” said Eustace querulously.

“Well, you know the voyage only takes eight days.”

“I’ve forgotten where I was.”

“You were saying what a devil of a chap she thought you. What happened? I suppose, when you actually came to propose, you found she was engaged to some other johnny?”

“Not at all! I asked her to be my wife, and she consented. We both agreed that a quiet wedding was what we wanted—she thought her father might stop the thing if he knew, and I was dashed sure my mother would—so we decided to get married without telling anybody. By now,” said Eustace, with a morose glance at the porthole, “I ought to have been on my honeymoon. Everything was settled. I had the license and the parson’s fee. I had been breaking in a new tie for the wedding.”

“And then you quarreled?”

“Nothing of the kind. I wish you would stop trying to tell me the story. I’m telling you. What happened was this: Somehow—I can’t make out how—Mother found out. And then, of course, it was all over. She stopped the thing.”

Sam was indignant. He thoroughly disliked his aunt Adeline, and his cousin’s meek subservience to her revolted him.

“Stopped it? I suppose she said, ‘Now, Eustace, you mustn’t!’ And you said, ‘Very well, Mother!’ and scratched the fixture.”

“She didn’t say a word. She never has said a word. As far as that goes, she might never have heard anything about the marriage.”

“Then, how do you mean she stopped it?”

“She pinched my trousers!” Eustace groaned. “All of them! The whole bally lot! She gets up long before I do, and she must have come into my room and cleaned it out while I was asleep. When I woke up and started to dress I couldn’t find a solitary pair of bags anywhere in the whole place. I looked everywhere. Finally, I went into the sitting-room where she was writing letters and asked if she had happened to see any anywhere. She said she had sent them all to be pressed. She said she knew I never went out in the mornings—I don’t as a rule—and they would be back by lunch time. A fat lot of use that was! I had to be at the church at eleven! Well, I told her I had a most important engagement with a man at eleven, and she wanted to know what it was and I tried to think of something; but it sounded pretty feeble and she said I had better telephone to the man and put it off. I did it, too. Rang up the first number in the book and told some fellow I had never seen in my life that I couldn’t meet him! He was pretty peeved, judging from what he said about my being on the wrong line. And Mother listening all the time, and I knowing that she knew—something told me that she knew—and she knowing that I knew she knew—I tell you it was awful!”

“And the girl?”

“She broke off the engagement. Apparently, she waited at the church from eleven till one-thirty and then began to get impatient. She wouldn’t see me when I called in the afternoon, but I got a letter from her saying that what had happened was all for the best, as she had been thinking it over and had come to the conclusion that she had made a mistake. She said something about my not being as dynamic as she had thought I was.”

“Did you explain about the trousers?”

“Yes. It seemed to make things worse. She said that she could forgive a man anything except being ridiculous.”

“I think you’re well out of it,” said Sam judicially. “She can’t have been much of a girl.”

“I feel that now. But it doesn’t alter the fact that my life is ruined. I have become a woman-hater. ‘Who was’t betrayed the Capitol? A woman. Who lost Marc Antony the world? A woman. Who was the cause of a long ten years’ war and laid at last old Troy in ashes? Woman! Destructive, damnable, deceitful woman!’ ”

Sam tried to put in a word, but Eustace stopped him: “If you have anything bitter and derogatory to say about women, say it, and I will listen eagerly. But if you merely wish to gibber about the ornamental exterior of some dashed girl you have been fool enough to get attracted by, go and tell it to the captain or the ship’s cat, or J. B. Midgeley. Do try to realize that I am a soul in torment! I think I shall take to drink.”

“Talking of that,” said Sam, “I suppose they open the bar directly we pass the three-mile limit. How about a small one?”

Eustace shook his head gloomily.

“Do you suppose I pass my time on board ship in gadding about and feasting? Directly the vessel begins to move, I go to bed and stay there. As a matter of fact, I think it would be wisest to go to bed now. Don’t let me keep you if you want to go on deck.”

“It looks to me,” said Sam, “as if I had been mistaken in thinking that you were going to be a ray of sunshine on the voyage.”

“Ray of sunshine!” said Eustace Hignett, pulling a pair of mauve pajamas out of the kit-bag. “I’m going to be a volcano!”

SAM left the stateroom and headed for the companion. He wanted to get on deck and ascertain if that girl was still on board. About now the sheep would be separating from the goats: the passengers would be on deck and their friends returning to the shore. A slight tremor in the boards on which he trod told him that this separation must have already taken place. The ship was moving. Was she on board or was she not? He reached the top of the stairs and passed out onto the crowded deck. And, as he did so, a scream, followed by confused shouting, came from the rail nearest the shore. He perceived that the rail was black with people hanging over it. They were all looking into the water.

Samuel Marlowe was not one of those who pass aloofly by when there is excitement toward. If a horse fell down in the street, he was always among those present, and he was never too busy to stop and stare at a blank window on which were inscribed the words “Watch this space!” To dash to the rail and shove a fat man in a tweed cap to one side was with him the work of a moment. He had thus an excellent view of what was going on, a view which he improved the next instant by climbing up and kneeling on the rail.

There was a man in the water, a man whose upper section, the only one visible, was clad in a blue jersey. He wore a derby hat, and from time to time, as he battled with the waves, he would put up a hand and adjust this more firmly on his head. A dressy swimmer.

Scarcely had he taken in this spectacle when Marlowe became aware of the girl he had met on the dock. She was standing a few feet away, leaning out over the rail with wide eyes and parted lips. Like everybody else, she was staring into the water.

As Sam looked at her the thought crossed his mind that here was a wonderful chance of making the most tremendous impression on this girl. What would she not think of a man who, reckless of his own safety, dived in and went boldly to the rescue? And there were men, no doubt, who would be chumps enough to do it, he thought, as he prepared to shift back to a position of greater safety.

At this moment, the fat man in the tweed cap, incensed at having been jostled out of the front row, made his charge. He had but been crouching, the better to spring. Now he sprang. His full weight took Sam squarely in the spine. There was an instant in which that young man hung, as it were, between sea and sky; then he shot down over the rail to join the man in the blue jersey, who had just discovered that his hat was not on straight and had paused to adjust it once more with a few skillful touches of the fingers.

IN THE brief interval of time which Marlowe had spent in the stateroom, chatting with Eustace about the latter’s bruised soul, some rather curious things had been happening above. Not extraordinary, perhaps, but curious. These must now be related. A story, if it is to grip the reader should, I am aware, go always forward. It should march. It should leap from crag to crag like the chamois of the Alps. If there is one thing I hate, it is a novel which gets you interested in the hero in chapter one and then cuts back in chapter two to tell you all about his grandfather. Nevertheless, at this point we must go back a space. We must return to the moment when, having deposited her Pekinese dog in her stateroom, the girl with the red hair came out again on deck. This happened just about the time when Eustace Hignett was beginning his narrative.

By now the bustle which precedes the departure of an ocean liner was at its height. Hoarse voices were crying, “All for the shore!” The girl went to the rail and gazed earnestly at the shore. She had the air of one who was waiting for someone to appear.

There was a rattle as the gangplank moved in-board and was deposited on the deck. The girl uttered a little cry of dismay. Then suddenly her face brightened, and she began to wave her arm to attract the attention of an elderly man with a red face, made redder by exertion, who had just forced his way to the edge of the dock and was peering up at the passenger-lined rail.

The boat had now begun to move slowly out of its slip, backing into the river. Ropes had been cast off, and an ever-widening strip of water appeared between the vessel and the shore. It was now that the man on the dock sighted the girl. She gesticulated at him. He gesticulated at her. She appeared helpless and baffled, but he showed himself a person of resource, of the stuff of which great generals are made.

The man on the dock took from his pocket a pleasantly rotund wad of currency bills. He produced a handkerchief, swiftly tied up the bills in it, backed to give himself room, and then, with all the strength of his arm, he hurled the bills in the direction of the deck. The action was greeted by cheers from a warm-hearted populace. Your New York crowd loves a liberal provider.

One says that the man hurled the bills in the direction of the deck, and that was exactly what he did. But the years had robbed his pitching arm of the limber strength which, forty summers back, had made him the terror of opposing boys’ baseball teams. He still retained a fair control, but he lacked steam. The handkerchief with its precious contents shot in a graceful arc toward the deck, fell short by a good six feet and dropped into the water, where it unfolded like a lily, sending twenty-dollar bills, ten-dollar bills, five-dollar bills, and an assortment of ones floating over the wavelets. The cheers of the citizenry changed to cries of horror. The girl uttered a plaintive shriek. The boat moved on.

It was at this moment that Mr. Oscar Swenson, one of the thriftiest souls who ever came out of Sweden, perceived that the chance of a lifetime had arrived for adding substantially to his little savings. By profession he was one of those men who eke out a precarious livelihood by rowing dreamily about the waterfront in skiffs. He was doing so now; and, as he sat meditatively in his skiff, having done his best to give the liner a good send-off by paddling round in circles, the pleading face of a twenty-dollar bill peered up at him. Mr. Swenson was not the man to resist the appeal. He uttered a sharp bark of ecstasy, pressed his derby hat firmly upon his brow and dived in. A moment later he had risen to the surface and was gathering up money with both hands.

He was still busy with this congenial task when a tremendous splash at his side sent him under again; and, rising for a second time, he observed with not a little chagrin that he had been joined by a young man in a blue flannel suit with an invisible stripe.

“Svensk!” exclaimed Mr. Swenson, or whatever it is that natives of Sweden exclaim in moments of justifiable annoyance. He resented the advent of this newcomer. He had been getting along fine and had had the situation well in hand. To him Sam Marlowe represented Competition, and Mr. Swenson desired no competitors in his treasure-seeking enterprise. He travels, thought Mr. Swenson, the fastest who travels alone.

Sam Marlowe had a touch of the philosopher in him. He had the ability to adapt himself to circumstances. It had been no part of his plans to come whizzing down off the rail into this singularly souplike water which tasted in equal parts of oil and dead rats; but, now that he was here, he was prepared to make the best of the situation. Swimming, it happened, was one of the things he did best, and somewhere among his belongings at home was a tarnished pewter cup which he had won at school in the “Saving Life” competition. He knew exactly what to do. You get behind the victim and grab him firmly under his arms, and then you start swimming on your back. A moment later, the astonished Mr. Swenson, who, being practically amphibious, had not anticipated that anyone would have the cool impertinence to try and save him from drowning, found himself seized from behind and towed vigorously away from a ten-dollar bill which he had almost succeeded in grasping. The spiritual agony caused by this assault rendered him mercifully dumb; though, even had he contrived to utter the rich Swedish oaths which occurred to him, his remarks could scarcely have been heard, for the crowd on the dock was cheering as one man. They had often paid good money to see far less gripping sights in the movies. They roared applause. The liner, meanwhile, continued to move stodgily out into midriver.

The only drawback to these life-saving competitions at school, considered from the standpoint of fitting the competitors for the problems of after-life, is that the object saved on such occasions is a leather dummy, and of all things in this world a leather dummy is perhaps the most placid and phlegmatic. It differs in many respects from an emotional Swedish gentleman, six feet high and constructed throughout of steel and indiarubber, who is being lugged away from cash which he has been regarding in the light of a legacy.

Mr. Swenson began immediately to struggle with all the violence at his disposal. His large, hairy hands came out of the water and swung hopefully in the direction where he assumed his assailant’s face to be.

Sam was not unprepared for this display. His researches in the art of life-saving had taught him that your drowning man frequently struggled against his best interests. In which case, cruel to be kind, one simply stunned the blighter. He decided to stun Mr. Swenson, though, if he had known that gentleman more intimately and had been aware that he had the reputation of possessing the thickest head on the waterfront he would have realized the magnitude of the task. Sam, ignorant of this, attempted to do the job with clenched fist, which he brought down as smartly as possible on the crown of the other’s derby hat.

It was the worst thing he could have done. Mr. Swenson thought highly of his hat, and this brutal attack upon it confirmed his gloomiest apprehensions. Now, thoroughly convinced that the only thing to do was to sell his life dearly, he wrenched himself round, seized his assailant by the neck, twined his arms about his middle, and accompanied him below the surface.

By the time he had swallowed his first pint and was beginning his second, Sam was reluctantly compelled to come to the conclusion that this was the end. The thought irritated him unspeakably. This, he felt, was just the silly, contrary way things always happened. Why should it be he who was perishing like this? Why not Eustace Hignett? Now, there was a fellow whom this sort of thing would just have suited. Broken-hearted Eustace Hignett would have looked on all this as a merciful release.

He paused in his reflections to try to disentangle the more prominent of Mr. Swenson’s limbs from about him. By this time he was sure that he had never met anyone he disliked so intensely as Mr. Swenson—not even his aunt Adeline. The man was a human octopus. Sam could count seven distinct legs twined round him and at least as many arms. It seemed to him that he was being done to death in his prime by a solid platoon of Swedes. He put his whole soul into one last effort . . . something seemed to give . . . he was free. Pausing only to try to kick Mr. Swenson in the face, Sam shot to the surface. Something hard and sharp prodded him in the head. Then something caught the collar of his coat; and, finally, spouting like a whale, he found himself dragged upward and over the side of a boat.

The time which Sam had spent with Mr. Swenson below the surface had been brief, but it had been long enough to enable the whole floating population of the North River to converge on the scene in scows, skiffs, launches, tugs, and other vessels. The fact that the water in that vicinity was crested with currency had not escaped the notice of these navigators and they had gone to it as one man. First in the race came the tug ‘Reuben S. Watson,’ the skipper of which, following a famous precedent, had taken his little daughter to bear him company. It was to this fact that Marlowe really owed his rescue. Women have often a vein of sentiment in them, where men can see only the hard business side of a situation; and it was the skipper’s daughter who insisted that the family boathook, then in use as a harpoon for spearing dollar bills, should be devoted to the less profitable but humane end of extricating the young man from a watery grave.

Accordingly, Sam found himself sitting on the deck of the tug engaged in the complicated process of restoring his faculties to the normal. In a sort of dream he perceived Mr. Swenson rise to the surface some feet away, adjust his derby hat, and, after one long look of dislike in his direction, swim off rapidly to intercept a five which was floating under the stern of a nearby skiff.

Sam sat on the deck and panted. He played on the boards like a public fountain. At the back of his mind there was a flickering thought that he wanted to do something, a vague feeling that he had some sort of an appointment which he must keep: but he was unable to think what it was.

“Well, aincher wet!” said a voice.

The skipper’s daughter was standing beside him, looking down commiseratingly. Of the rest of the family all he could see was the broad blue seats of their trousers as they leaned hopefully over the side in the quest for wealth.

“Yessir! You sure are wet! Gee! I never seen anyone so wet! I seen wet guys, but I never seen anyone so wet as you. Yessir, you’re certainly wet!”

“It’s the water,” said Sam.

“Wotcha do it for?” asked the girl. “Wotcha do a Brodie for off’n that ship?”

Sam uttered a sharp cry. He had remembered.

“Where is she?”

“Where’s who?”

“The liner.”

“She’s off down the river, I guess. Wotcha expect her to do? She’s gotta get over to the other side, ain’t she?”

Sam sprang to his feet and looked wildly about him: “I must get back. Isn’t there any way of getting back?”

“Well, you could catch up with her at quarantine out in the bay. She’ll stop to let the pilot off.”

“Can you take me to quarantine?”

The girl glanced doubtfully at the seat of the nearest pair of trousers.

“Well, we could,” she said. “But Pa’s kind of set in his ways, and right now he’s fishing for dollar bills with the boathook. He’s apt to get sorta mad if he’s interrupted.”

“I’ll give him fifty dollars if he’ll put me on board.”

“Pa! Commere! Wantcha!”

The trousers did not even quiver. But this girl was a girl of decision. There was some nautical implement resting in a rack convenient to her hand. It was long, solid, and constructed of one of the harder forms of wood. Deftly extracting this from its place she smote her inoffensive parent on the only visible portion of him. He turned sharply, exhibiting a red bearded face.

“Pa, this gen’man wants to be took aboard the boat at quarantine. He’ll give you fifty berries.”

The wrath died out of the skipper’s face like the slow turning down of a lamp. The fishing had been poor, and so far he had managed to secure only a single two-dollar bill.

“Fifty berries!”

“Fifty seeds!” the girl assured him.

Twenty minutes later Sam was climbing up the side of the liner as it lay towering over the tug like a mountain. His clothes hung about him clammily. He squelched as he walked.

A kindly-looking old gentleman who was smoking a cigar by the rail regarded him with open eyes.

“My dear sir, you’re very wet,” he said.

Sam passed him with a cold face and hurried through the door leading to the companionway.

“Good lord, sir! You’re very wet!” said a steward in the doorway of the dining-saloon.

“You are wet,” said a stewardess in the passage.

Sam raced for his stateroom. He bolted in and sank on the lounge. In the lower berth Eustace Hignett was lying with closed eyes. He opened them languidly—then stared.

“Hullo!” he said. “I say! You’re wet.”

Sam removed his clinging garments and hurried into a new suit. He was in no mood for conversation, and Eustace Hignett’s frank curiosity jarred upon him. Happily, at this point a sudden shivering of the floor and a creaking of woodwork proclaimed the fact that the vessel was under way again, and his cousin, turning pea green, rolled over on his side with a hollow moan. Sam finished buttoning his waistcoat and went out.

He was passing the Inquiry Bureau on the C-Deck, striding along with bent head and scowling brow, when a sudden exclamation caused him to look up, and the scowl was wiped from his brow as with a sponge. For there stood the girl he had met on the dock. With her was a superfluous young man who looked like a parrot.

“Oh, how are you?” asked the girl breathlessly.

“Splendid, thanks,” said Sam.

“Didn’t you get very wet?”

“I did get a little damp.”

There was a pause.

“Oh!” said the girl, “may I—Mr.——?”

“Marlowe.”

“Mr. Marlowe. Mr. Bream Mortimer.”

“Nearly got left behind,” said Bream Mortimer.

“Yes, nearly.”

“No joke getting left behind.”

“No.”

“Have to take the next boat. Lose a lot of time,” said Mr. Mortimer, driving home his point.

The girl had listened to these intellectual exchanges with impatience. She now spoke again.

“Oh, Bream!”

“Hello?”

“Do be a dear and run down to the saloon and see if it’s all right about our places for luncheon.”

“It is all right. The table steward said so.”

“Yes, but go and make certain.”

“All right.”

He hopped away, and the girl turned to Sam with shining eyes.

“Oh, Mr. Marlowe, you oughtn’t to have done it! Really, you oughtn’t! You might have been drowned! But I never saw anything so wonderful. It was like the stories of knights who used to jump into lions’ dens after gloves!”

“Yes?” said Sam, a little vaguely.

“But you shouldn’t have bothered, really! It’s all right now. I’d quite forgotten that Mr. Mortimer was to be on board. He has given me all the money I shall need. You see, it was this way: I had to sail on this boat in rather a hurry. Father’s head clerk was to have gone to the bank and got some money and met me on board and given it to me, but the silly old man was late, and when he got to the dock they had just pulled in the gangplank. So he tried to throw the money to me in a handkerchief, and it fell into the water. But you shouldn’t have dived in after it.”

“Oh, well!” said Sam, straightening his tie, with a quiet, brave smile. He had never expected to feel grateful to that obese bounder who had shoved him off the rail, but now he would have liked to seek him out and offer him his bank roll.

“You really are the bravest man I ever met!”

“Oh, no!”

“It is all right,” said Mr. Mortimer, reappearing suddenly. “I saw a couple of stewards, and they both said it was all right. So it’s all right.”

“Splendid,” said the girl. “Oh, Bream! Do be an angel, and run along to my stateroom and see if Pinky-Boodles is quite comfortable. He may be feeling lonely. Chirrup to him a little. Run along!”

Mr. Mortimer ran along. He had the air of one who feels that he needs only a peaked cap and a uniform two sizes too small for him to be a properly equipped messenger boy.

“And, as Bream was saying,” resumed the girl, “you might have been left behind.”

“That,” said Sam, edging a step closer, “was the thought that tortured me, the thought that a friendship so delightfully begun—”

“But it hadn’t begun. We have never spoken to each other before now.”

“Have you forgotten? On the dock?”

Sudden enlightenment came into her eyes.

“Oh, you are the man poor Pinky-Boodles bit!”

“I shall always remember that it was Pinky who first brought us together. Would you care for a stroll on deck?”

“Not just now, thanks. I must be getting back to my room to finish unpacking. After luncheon, perhaps.”

“I will be there. By the way, you know my name, but—”

“Oh, mine?” She smiled brightly. “It’s funny that a person’s name is the last thing one thinks of asking. Mine is Bennett.”

“Bennett!”

“Wilhelmina Bennett. My friends,” she said softly as she turned away, “call me Billie!”

FOR some moments Sam remained where he was, staring after the girl as she flitted down the passage. He felt dizzy. Listening to Eustace Hignett’s story of his blighted romance, Sam had formed an unflattering opinion of this Wilhelmina Bennett, who had broken off her engagement simply because on the day of the marriage his cousin had been short of the necessary wedding garment. He had, indeed, thought a little smugly how different his goddess of the red hair was from the object of Eustace Hignett’s affections. And now they had proved to be one and the same. It was disturbing.

After all . . . poor old Eustace . . . quite a good fellow, no doubt in many ways . . . but, coming down to brass tacks, what was there about Eustace that gave him any license to monopolize the affections of a wonderful girl? Where, in a word, did Eustace Hignett get off? He made a tremendous grievance of the fact that she had broken off the engagement; but what right had he to go about the place expecting her to be engaged to him? Eustace Hignett, no doubt, looked upon the poor girl as utterly heartless. Marlowe regarded her behavior as thoroughly sensible. She had made a mistake, and, realizing this at the eleventh hour, she had had the force of character to correct it. He was sorry for poor old Eustace, but he really could not permit the suggestion that Wilhelmina Bennett—her friends called her Billie—had not behaved in a perfectly splendid way throughout.

A consuming desire came over him to talk about the girl to someone. Obviously indicated as the party of the second part was Eustace Hignett. If Eustace was still capable of speech—and after all the boat was hardly rolling at all—he would enjoy a further chat about his ruined life.

The exhibit was lying on his back staring at the roof of the berth. By lying absolutely still and forcing himself to think of purely inland scenes and objects, he had contrived to reduce the green in his complexion to a mere tinge. But it would be paltering with the truth to say that he felt debonair. He received Sam with a wan austerity.

“Sit down!” he said. “Don’t stand there swaying like that. I can’t bear it.”

“Why, we aren’t out of the harbor yet. Surely, you aren’t going to be seasick already.”

“I can issue no positive guarantee. Perhaps if I can keep my mind off it. . . . I have had good results for the last ten minutes by thinking steadily of the Sahara. There,” said Eustace Hignett with enthusiasm, “is a place for you! That is something like a spot! Miles and miles of sand, and not a drop of water anywhere!”

Sam sat down on the lounge.

“You’re quite right. The great thing is to concentrate your mind on other topics. Why not, for instance, tell me some more about your unfortunate affair with that girl—Billie Bennett, I think you said her name was.”

“Wilhelmina Bennett. Where on earth did you get the idea that her name was Billie?”

“I had a notion that girls called Wilhelmina were sometimes Billie to their friends.”

“I never call her anything but Wilhelmina. But I really cannot talk about it. The recollection tortures me.”

“That’s just what you want. It’s the counter-irritation principle. Persevere, and you’ll soon forget that you’re on board ship at all.”

“There’s something in that,” admitted Eustace reflectively. “It’s very good of you to be so sympathetic and interested.”

“My dear fellow . . . anything that I can do. . . . Where did you meet her first, for instance?”

“At a dinner—” Eustace Hignett broke off abruptly. He had a good memory, and he had just recollected the fish they had served at that dinner—a flabby and exhausted-looking fish, half sunk beneath the surface of a thick white sauce.

“And what struck you most forcibly about her at first? Her lovely hair, I suppose?”

“How did you know she had lovely hair?”

“My dear chap, I naturally assumed that any girl with whom you fell in love would have nice hair.”

“Well, you are perfectly right, as it happens. Her hair was remarkably beautiful. It was red.”

“Like autumn leaves with the sun on them!” said Marlowe ecstatically.

“What an extraordinary thing! That is an absolutely exact description. Her eyes were a deep blue. . . .”

“Or, rather, green.”

“What do you know about the color of her eyes?” demanded Eustace heatedly. “Am I telling you about her, or are you telling me?”

“My dear old man, don’t get excited. Don’t you see I am trying to construct this girl in my imagination, to visualize her? I don’t pretend to doubt your special knowledge; but, after all, green eyes generally do go with red hair, and there are all shades of green. There is the bright green of meadow grass, the dull green of the uncut emerald, the faint yellowish green of your face at the present moment.”

“Don’t talk about the color of my face! Now you’ve gone and reminded me, just when I was beginning to forget.”

“Awfully sorry! Stupid of me! Get your mind off it again—quick! This Miss Bennett now, what did she like talking about?”

“Well, for one thing she was very fond of poetry. It was that which first drew us together.”

“Poetry!” Sam’s

heart sank a little. He had read a certain amount of poetry at school, and

once he had won a prize of three shillings and sixpence for the last line of a

limerick in a competition in a weekly paper; but he was self-critic enough to

know that poetry was not his long suit. Still, there was a library on board

ship, and no doubt it would be possible to borrow the works of some standard

poet and bone them up from time to time.

“Poetry!” Sam’s

heart sank a little. He had read a certain amount of poetry at school, and

once he had won a prize of three shillings and sixpence for the last line of a

limerick in a competition in a weekly paper; but he was self-critic enough to

know that poetry was not his long suit. Still, there was a library on board

ship, and no doubt it would be possible to borrow the works of some standard

poet and bone them up from time to time.

“Any special poet?”

“Well, she seemed to like my stuff. You never read my sonnet-sequence on Spring, did you?”

“No. What other poets did she like besides you?”

“Tennyson principally,” said Eustace Hignett, with a reminiscent quiver in his voice. “The hours we have spent together reading the ‘Idylls of the King’!”

“The which of what?” inquired Sam, taking a pencil from his pocket and shooting out a cuff.

“The ‘Idylls of the King.’ My good man, I know you have a soul which would be considered inadequate by a common earthworm, but you have surely heard of Tennyson’s ‘Idylls of the King’?”

“Oh, those! Why, my dear old chap: Tennyson’s ‘Idylls of the King’! Well, I should say! Have I heard of Tennyson’s ‘Idylls of the King’? Well, really! I suppose you haven’t a copy with you on board by any chance?”

“There is a copy in my kit-bag. The very one we used to read together. Take it and keep it, or throw it overboard. I don’t want to see it again.”

Sam prospected among the shirts, collars, and trousers in the bag and presently came upon a morocco-bound volume. He laid it beside him on the lounge.

“Little by little, bit by bit,” he said, “I am beginning to form a sort of picture of this girl, this—what was her name again? Bennett—this Miss Bennett. You have a wonderful knack of description. You make her seem so real and vivid. Tell me some more about her. She wasn’t keen on golf, by any chance, I suppose?”

“I believe she did play. The subject came up once, and she seemed rather enthusiastic. Then, of course, there was always the matter of that dog of hers. She had a dog, you know, a snappy brute of a Pekinese. If there was ever any shadow of disagreement between us, it had to do with that dog.”

“I see!” said Sam. He shot his cuff once more and wrote on it: “Dog—conciliate.” “Yes, of course, that must have wounded her.”

“Well, I hate dogs,” said Eustace Hignett querulously. “I remember Wilhelmina once getting quite annoyed with me because I refused to step in and separate a couple of the brutes, absolute strangers to me, that were fighting in the street. I reminded her that we were all fighters nowadays, that life itself was in a sense a fight; but she wouldn’t be reasonable about it. She said that Sir Galahad would have done it like a shot.”

Sam rose. His heart was light. He had never, of course, supposed that the girl was anything but perfect; but it was nice to find his high opinion of her corroborated by one who had no reason to exhibit her in a favorable light. He understood her point of view and sympathized with it. An idealist, how could she trust herself to Eustace Hignett? How could she be content with a craven, who, instead of scouring the world in the quest for deeds of derring do, had fallen down so lamentably on his first assignment? The man a girl like Wilhelmina Bennett required for a husband was somebody entirely different.

Swelled almost to bursting point with these reflections, he went on deck to join the ante-luncheon promenade. He saw Billie almost at once. She had put on one of these nice sacky sports coats which so enhance feminine charms, and was striding along the deck with the breeze playing in her vivid hair, like the female equivalent of a Viking. Beside her walked young Mr. Bream Mortimer.

“Oh, there you are, Mr. Marlowe!”

“Oh, there you are,” said Bream Mortimer, with a slightly different inflection.

“I thought I’d like a breath of fresh air before lunch,” said Sam.

“Oh, Bream!” said the girl. “Do be a darling and take this great heavy coat of mine down to my stateroom, will you? I had no idea it was so warm.”

“All right,” said Bream moodily.

He trotted along. There are moments when a man feels that all he needs in order to be a delivery wagon is a horse and a driver.

“He had better chirrup to the dog while he’s there, don’t you think?” suggested Sam. He felt that a resolute man with legs as long as Bream’s might well deposit a cloak on a berth and be back under the half-minute.

“Oh, yes! Bream! While you’re down there just chirrup a little more to poor Pinky. He does appreciate it so!”

Bream disappeared. It is not always easy to interpret emotion from a glance at a man’s back; but Bream’s back looked like that of a man to whom the thought has occurred that, given a couple of fiddles and a piano, he would have made a good hired orchestra.

“How is your dear little dog, by the way?” inquired Sam solicitously, as he fell into step by her side.

“Much better now, thanks. I’ve made friends with a girl on board, did you ever hear her name—Jane Hubbard; she’s a rather well-known big-game hunter, and she fixed up some sort of a mixture for Pinky which did him a world of good. It’s very nice of you to speak so affectionately of poor Pinky, when he bit you.”

“Animal spirits!” said Sam tolerantly. “Pure animal spirits! I like to see them. But, of course, I love all dogs. I only wish they didn’t fight so much. I’m always stopping dog fights.”

“I do admire a man who knows what to do at a dog fight. I’m afraid I’m rather helpless myself. There never seems anything to catch hold of.” She looked down. “Have you been reading? What is the book?”

“It’s a volume of Tennyson.”

“Are you fond of Tennyson?”

“I worship him,” said Sam reverently. “Those—” he glanced at his cuff— “those ‘Idylls of the King’! I do not like to think what an ocean voyage would be if I had not my Tennyson with me.”

“We must read him together. He is my favorite poet!”

“We will! There is something about Tennyson . . .”

“Yes, isn’t there! I’ve felt that myself so often!”

“Some poets are whales at epics and all that sort of thing, while others call it a day when they’ve written something that runs to a couple of verses; but where Tennyson had the bulge was that his long game was just as good as his short. He was great off the tee, and a marvel with his chip-shots.”

“That sounds as though you played golf.”

“When I am not reading Tennyson, you can generally find me out on the links. Do you play?”

“I love it. How extraordinary that we should have so much in common. We really ought to be great friends.”

He was pausing to select the best of three replies when the luncheon bugle sounded.

“Oh, dear!” she cried. “I must rush. But we shall see one another again up here afterward?”

“We will,” said Sam.

“We’ll sit and read Tennyson.”

“Fine! Er—you and I and Mortimer?”

“Oh, no, Bream is going to sit down below and look after poor Pinky.”

“Does he—does he know he is?”

“Not yet,” said Billie. “I’m going to tell him at lunch.”

IT WAS the fourth morning of the voyage. Of course, when this story is done in the movies they won’t be satisfied with a bald statement like that; they will have a Spoken Title or a Cut-Back Sub-Caption, or whatever they call the thing in the low dens where motion-picture scenario-lizards do their dark work, which will run:

and

so, calm and golden, the days

went by, each fraught with hope

and youth and

sweetness, linking

two young hearts in silken fetters

forged by the laughing love-god

and the males in the audience will shift their chewing gum to the other cheek and take a firmer grip of their companions’ hands, and the man at the piano will play, ‘Everybody wants a key to my cellar,’ or something equally appropriate. But I prefer the plain, frank statement that it was the fourth day of the voyage. That is my story, and I mean to stick to it.

Samuel Marlowe, muffled in a bathrobe, came back to the stateroom from his tub. His manner had the offensive jauntiness of the man who has had a cold bath when he might just as easily have had a hot one. He felt strong and happy and exuberant.

It was not merely the spiritual pride induced by a cold bath that was uplifting this young man. The fact was that, as he towelled his glowing back, he had suddenly come to the decision that this very day he would propose to Wilhelmina Bennett. Yes, he would put his fortune to the test, to win or lose it all. True, he had known her for four days only; but what of that?

Nothing in the way of modern progress is more remarkable than the manner in which the attitude of your lover has changed concerning proposals of marriage. The courtship of the modern young man can hardly be called a courtship at all. His methods are those of Sir W. S. Gilbert’s Alphonso.

Alphonso, who for cool assurance all creation licks,

He up and said to Emily, who has cheek enough for six:

“Miss Emily, I love you. Will you marry? Say the word!”

And Emily said: “Certainly, Alphonso, like a bird!”

Sam Marlowe was a warm supporter of the Alphonso method.

Sam let down the trick basin which hung beneath the mirror, and, collecting his shaving materials, began to lather his face.

“I am the Bandolero!” sang Sam blithely through the soap, “I am, I am the Bandolero! Yes, yes, I am the Bandolero!”

The untidy heap of bedclothes in the lower berth stirred restlessly.

“Oh, heavens!” said Eustace Hignett, thrusting out a tousled head.

Sam regarded his cousin with commiseration. Horrid things had been happening to Eustace during the last few days, and it was quite a pleasant surprise each morning to find that he was still alive.

“Feeling bad again, old man?”

“I was feeling all right,” replied Hignett churlishly, “until you began the farmyard imitations. What sort of a day is it?”

“Glorious! The sea . . .”

“Don’t talk about the sea!”

“Sorry! The sun is shining brighter than it has ever shone in the history of the race. Why don’t you get up?”

“Nothing will induce me to get up.” He eyed Sam sourly. “You seem decidedly pleased with yourself this morning!”

Sam dried the razor carefully and put it away. He hesitated. Then the desire to confide in somebody got the better of him.

“The fact is,” he said apologetically, “I’m in love!”

“In love!” Eustace Hignett sat up and bumped his head sharply against the berth above him. “Has this been going on long?”

“Ever since the voyage started.”

“I think you might have told me,” said Eustace reproachfully. “Who is she?”

“Oh, a girl I met on board.”

“Don’t do it!” said Eustace Hignett solemnly. “As a friend, I entreat you not to do it!”

“Don’t do what?”

“Propose to her. I can tell by the glitter in your eye that you are intending to propose to this girl—probably this morning. Don’t do it. Women are the devil, whether they marry you or jilt you. Do you realize that women wear black evening dresses that have to be hooked up in a hurry when you are late for the theatre, and that, out of sheer wanton malignity, the hooks and eyes on those dresses are also made black? Do you realize—?”

“Oh, I’ve thought it all out.”

“And take the matter of children: How would you like to become the father—and a mere glance around you will show you that the chances are enormously in favor of such a thing happening—of a boy with spectacles and protruding front teeth who asks questions all the time? Out of six small boys whom I saw when I came on board, four wore spectacles and had teeth like rabbits. The other two were equally revolting in different styles. How would you like to become the father—?”

“There is no need to be indelicate,” said Sam stiffly. “A man must take these chances.”

“Give her the miss in balk,” pleaded Hignett. “Stay down here for the rest of the voyage. You can easily dodge her when you get to Southampton. And, if she sends messages, say you’re ill and can’t be disturbed.”

Sam gazed at him, revolted. More than ever he began to understand how it was that a girl with ideals had broken off her engagement with this man. He finished dressing and, after a satisfying breakfast, went on deck.

IT WAS, as he had said, a glorious morning. The sight of Billie Bennett, trim and gleaming in a pale green sweater and a white skirt, had the effect of causing Marlowe to alter the program which he had sketched out. Proposing to this girl was not a thing to be put off till after luncheon. It was a thing to be done now, and at once. The finest efforts of the finest cooks in the world could not put him in better form than he felt at present.

“Good morning, Miss Bennett.”

“Good morning, Mr. Marlowe.”

“Isn’t it a perfect day?”

“Wonderful!”

“Shall we walk round?” said Billie.

Sam glanced about him. It was the time of day when the promenade deck was always full. Passengers in cocoons of rugs lay on chairs, waiting in a dull trance till the steward should arrive with the eleven o’clock soup. Others, more energetic, strode up and down. From the point of view of a man who wished to reveal his most sacred feelings to a beautiful girl, the place was practically Fifth Avenue and Forty-second Street.

“It’s so crowded,” he said. “Let’s go on to the upper deck.”

“All right. You can read to me. Go and fetch your Tennyson.”

Sam felt that fortune was playing into his hands. His four-days acquaintance with the bard had been sufficient to show him that the man was there forty ways when it came to writing about love.

He threaded his way through a maze of boats, ropes, and curious-shaped steel structures which the architect of the ship seemed to have tacked on at the last moment in a spirit of sheer exuberance. Above him towered one of the funnels, before him a long, slender mast. He hurried on, and presently came upon Billie, sitting on a garden seat, backed by the white roof of the smoke-room; beside this was a small deck, which seemed to have lost its way and strayed up here all by itself. It was the deck on which one could occasionally see the patients playing an odd game with long sticks and bits of wood—not shuffle-board but something even lower in the mental scale. This morning, however, the devotees of this pastime were apparently under proper restraint, for the deck was empty.

“This is jolly,” he said, sitting down beside the girl and drawing a deep breath of satisfaction.

“Yes, I love this deck. It’s so peaceful.”

“It’s the only part of the ship where you can be reasonably sure of not meeting stout men in flannels and nautical caps. An ocean voyage always makes me wish that I had a private yacht.”

“It would be nice.”

“A private yacht,” repeated Sam, sliding a trifle closer. “We would sail about, visiting desert islands which lay like jewels in the heart of tropic seas.”

“We?”

“Most certainly we. It wouldn’t be any fun if you were not there.”

“That’s very complimentary.”

“Well, it wouldn’t. I’m not fond of girls as a rule—”

“Oh, aren’t you?”

“No!” said Sam decidedly. It was a point which he wished to make clear at the outset. “Not at all fond. My friends have often remarked upon it. A palmist once told me that I had one of those rare spiritual natures which cannot be satisfied with substitutes but must seek and seek till they find their soul-mate. When other men all round me were frittering away their emotions in idle flirtations which did not touch their deeper natures, I was . . . I was— Well, I wasn’t; if you see what I mean.”

“Oh, you wasn’t . . . weren’t?”

“No. Some day I knew I should meet the only girl I could possibly love, and then I would pour out upon her the stored-up devotion of a lifetime, lay an unblemished heart at her feet, fold her in my arms and say, ‘At last!’ ”

“How jolly for her. Like having a circus all to one’s self.”

“Well, yes,” said Sam, after a momentary pause.

“When I was a child I always thought that that would be the most wonderful thing in the world.”

“The most wonderful thing in the world is love, a pure and consuming love, a love which—”

“Oh, hello!” said a voice.

All through this scene, right from the very beginning of it, Sam had not been able to rid himself of a feeling that there was something missing. The time and the place and the girl—they were all present and correct; nevertheless, there was something missing, some familiar object which seemed to leave a gap. He now perceived that what had caused the feeling was the complete absence of Bream Mortimer. He was absent no longer.

“Oh, hello, Bream!” said Billie.

“Hullo!” said Sam.

“Hullo!” said Bream Mortimer. “Here you are!”

There was a pause.

“I thought you might be here,” said Bream.

“Yes, here we are,” said Billie.

“Yes, we’re here,” said Sam.

There was another pause.

“Mind if I join you?” said Bream.

“N-no,” said Billie.

“N-no,” said Sam.

“No,” said Billie again. “No . . . that is to say . . . oh no, not at all.”

There was a third pause.

“On second thoughts,” said Bream, “I believe I’ll take a stroll on the promenade deck, if you don’t mind.”

They said they did not mind. Bream Mortimer, having bumped his head twice against overhanging steel ropes, melted away.

“Who is that fellow?” demanded Sam wrathfully.

“He’s the son of Father’s best friend.”

Sam started. Somehow, this girl had always been so individual to him that he had never thought of her having a father.

“We have known each other all our lives,” continued Billie. “Father thinks a tremendous lot of Bream.”

“I think of him as little as I can.”

“I suppose it was because Bream was sailing by her that Father insisted on my coming over on this boat. I’m in disgrace, you know. I was cabled for and had to sail at a few days’ notice. I—”

“Oh, hello!”

“Why, Bream!” said Billie, looking at him as he stood on the old spot in the same familiar attitude, with rather less affection than the son of her father’s best friend might have expected. “I thought you said you were going down to the promenade deck.”

“I did go down to the promenade deck. And I’d hardly got there, when a fellow who’s getting up the ship’s concert to-morrow night nobbled me to do a couple of songs. He wanted to know if I knew anyone else who would help. I came up to ask you,” he said to Sam, “if you would do something.”

“No,” said Sam. “I won’t.”

“He’s got a man who’s going to lecture on deep-sea fish, and a couple of women who both want to sing ‘The Rosary,’ but he’s still an act or two short. Sure you won’t rally around?”

“Quite sure.”

“Oh, all right.” Bream Mortimer hovered wistfully above them.

“Oh, Bream!” said Billie.

“Hello?”

“Do be a pet and go and talk to Jane Hubbard. I’m sure she must be feeling lonely. I left her all by herself down on the next deck.”

A look of alarm spread itself over Bream’s face.

“Jane Hubbard! Oh, say, have a heart!”

“She’s a very nice girl.”

“She’s so darned dynamic. She looks at you as if you were a giraffe or something and she would like to take a pot at you with a rifle.”

“Nonsense! Run along. Get her to tell you some of her big-game hunting experiences. They are most interesting.”

Bream drifted sadly away.

“I don’t blame Miss Hubbard,” said Sam.

“What do you mean?”

“Looking at him as if she wanted to pot at him with a rifle. I should like to do it myself. What were you saying when he came up?”

“Oh, don’t let’s talk about me. Read me some Tennyson.”

Sam opened the book very willingly. Infernal Bream Mortimer had absolutely shot to pieces the spell which had begun to fall on them at the beginning of their conversation. Only by reading poetry, it seemed to him, could it be recovered. And when he saw the passage at which the volume had opened he realized that his luck was in.

He cleared his throat.

“O, let the solid ground

Not fail beneath my feet

Before my life has found

What some have found so sweet;

Then let come what come may,

What matter if I go mad,

I shall have had my day.

“Let the sweet heavens endure,

Not close and darken above me

Before I am quite, quite sure

That there is one to love me. . . .”

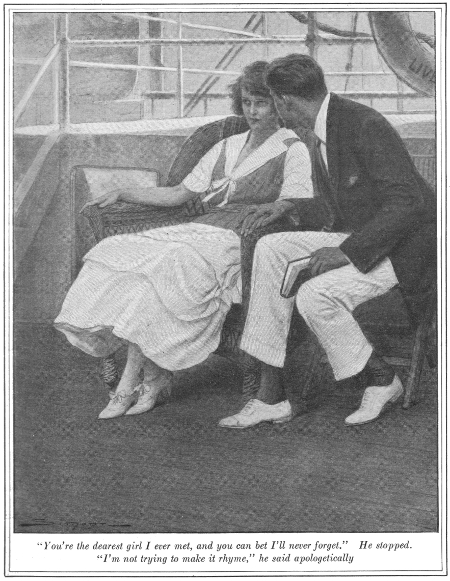

This was absolutely topping. It was like diving off a springboard. He could see the girl sitting with a soft smile on her face, her eyes, big and dreamy, gazing out over the sunlit sea. He laid down the book and took her hand.

“There is something,” he began in a low voice, “which I have been trying to say ever since we met, something which I think you must have read in my eyes.”

Her head was bent. She did not withdraw her hand.

“Until this

voyage began,” he went on, “I did not know what life meant. And then I saw

you! It was like the gate of heaven opening. You’re the dearest girl I ever

met, and you can bet I’ll never forget—” He stopped. “I’m not trying to make

it rhyme,” he said apologetically. “Billie, don’t think me silly . . . I mean

. . . if you had the merest notion, dearest . . . I don’t know what’s the matter

with me! . . . Billie darling, you are the only girl in the world! I have been

looking for you for years and years, and I have found you at last, my

soul-mate. Surely this does not come as a surprise to you? That is, I mean,

you must have seen that I’ve been keen. . . . There’s that damned Walt Mason

stuff again!” His eyes fell on the volume beside him, and he uttered an

exclamation of enlightenment. “It’s those poems!” he cried. “I’ve been

boning them up to such an extent that they’ve got me doing it, too. What I’m

trying to say is, Will you marry me?”

“Until this

voyage began,” he went on, “I did not know what life meant. And then I saw

you! It was like the gate of heaven opening. You’re the dearest girl I ever