Windsor Magazine, August 1906

Illustrated by G. Hillyard Swinstead

IF I have one fault—which I am not prepared to admit—it is that I am too good-natured. I remember on one occasion, when staying in the country with a lady who had known me from boyhood, protesting in a restrained, gentlemanly manner when her youthful son began to claw me at breakfast. At breakfast, I’ll trouble you, and an early one at that! “Well, James,” she said, “I always thought that you were good-natured, whatever else you were!” A remark which, besides containing a nasty innuendo in the latter half of it, struck me as passing all existing records in Cool Cheek. And it stood as a record till the day that Jervis rang me up on the telephone and broached the matter of Mr. Morley-Davenport.

It is no use to grumble, I suppose. One cannot alter one’s nature. There it is, and there’s an end of it. But personally I have always found it a minor curse. People ask me to do things, and expect me to oblige them, when they would not dream of making the same request of most of the men I know. And they thrive on it. Do a man a good turn once, as somebody says, and after that he thinks he has a right to come and sit on your lap and help himself out of your pockets.

Looking back over the episodes which have arisen from this abuse of my angelic temperament, I recall the Adventure of a Ribbon I tried to match for an Aunt of Mine, the Curious Affair of the Vicar’s Garden-Party, and a host of others, prominent among which is the Dark and Sinister Case of the Brothers Barlow, the most recent of all my ordeals.

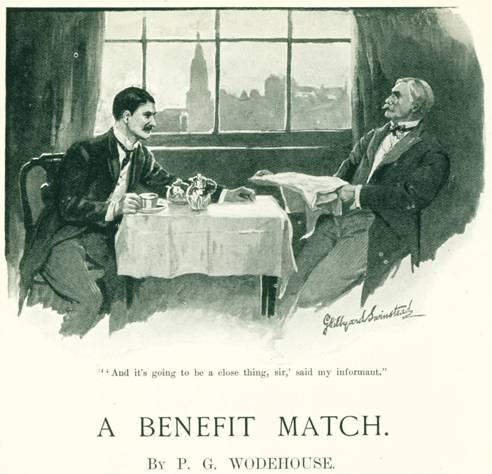

It occurred only last summer. I was having tea at my club when the thing may be said to have begun. The club is described in Whitaker as “social and political,” and at that time it seemed to me to overdo both qualities. The political atmosphere at the moment was disturbed by a series of by-elections, and members, whom I did not know by sight, were developing a habit of sitting down beside me and saying: “Interesting contest, that at ——,” wherever the place might be. In this case it was at Stapleton, in Surrey. The Stapleton election, I gathered from an old gentleman who had cornered me and was giving me his views on the crisis, was in a most interesting condition. If Morley-Davenport—who was, I gathered, “our man”—could pull it off, it would be a most valuable thing for the party. On the other hand, if he could not pull it off, as was not at all unlikely, it would be an equally damaging blow for the party.

“And it’s going to be a close thing, sir,” said my informant—“an uncommonly close thing.”

“Sporting finish,” I agreed, feeling rather bored. I wanted to get at the evening paper, to see what sort of a game Middlesex were making of it with Surrey.

“A desperately close thing,” said my old gentleman.

Here the door of the smoking-room opened, and a boy appeared. When anybody is wanted at our club, it is customary for a boy to range the building, chanting the name at intervals in a penetrating treble—

“Mis-tah Innes!”

I am Mr. Innes.

“Excuse me,” I said to the politician.

Somebody had rung me up on the telephone. I went downstairs, shut myself up in the box, and put the engine to my ear.

“Hullo?”

“That you, James?”

I recognised the voice. It was that of Jervis, a man who sometimes played for the Weary Willies on their Devonshire tour.

“Yes. That you, Jervis? What’s the matter? Why didn’t you come and look me up here?”

“No time. I’m off in ten minutes. I’m ’phoning from Waterloo. Never been so busy in my life. Working twenty-four hours a day, three-minute interval for meals. This election business, you know. Down at Stapleton. It’s going to be the hottest finish on record.”

“So a battered relic in here was telling me just now. Dash along. You’ve interrupted me in the middle of my tea, and I’ve had to leave half a crumpet alone with the battered one, whom I don’t trust an inch. I saw him looking hungrily at it when I went out. What’s up with you?”

“Look here, James, you were always a good-natured sort of chap——”

I started, as one who sees a surreptitious snake in the undergrowth.

“Jervis,” I said.

“Hullo, are you there?”

“Of course I am. Where did you think I was? Look here, if you want me to act in amateur theatricals again, you’d save yourself trouble by ringing off at once.”

“No, no.”

“Or if it’s anything to do with a bazaar——”

“No, no, nothing of that sort. It’s about a cricket match. I suppose you’re skippering the Weary Willies against Stapleton?”

“So that’s why the name sounded familiar. I’d forgotten we’d got a match on there. Yes, I am. Why?”

“Then just listen carefully for a minute. I must hurry, or I shall miss that train. You know, I’m agent for old Morley-Davenport, don’t you? Well, anyhow, I am. It’s the tightest thing you ever saw, but I believe we shall get him in all right. I had a great idea the other day. It was this way. I don’t know if you know Stapleton. It’s a sporting constituency. Half the voters live for nothing else but games. The serious politicians of the neighbourhood are about even, but there’s quite a decent squad of electors who’d vote either way. It all depends which man takes their fancy. My idea was this. The Weary Willies’ match always excites people down here, and I’ve arranged that old M.-D. shall play for Stapleton. You see the idea? Our sporting candidate. Genuine son of Britain, and so on. It will be the biggest advertisement on earth.”

“Not much of an advertisement if your son of Britain takes an egg.”

“But he won’t. That’s where you come in.”

“Oh?”

“Yes. Are you there? Keep on listening. I want you to square the bowlers, and let our man make a few.”

“Is that all?” I said.

“Quite a simple thing. Morley-Davenport isn’t in his first youth exactly, but he’s a sturdy old chap, and used to play cricket once.”

“Friend of Alfred Mynn’s?”

“That’s about the date. Still, he could make a few off real tosh. Just one or two loose ones to leg. I wish you would, old man. You know the Stapleton match isn’t such a big affair for the Weary Willies. It doesn’t matter much whether you win or lose. And, besides, you’re bound to win. You need only let him get about twenty. That would see us through. And Stapleton haven’t any bowling. Are you on?”

“Why doesn’t he try some other dodge? Why not kiss a baby or two?”

“My dear chap, we’ve kissed babies till our lips are worn through. This is the only way. Are you on?”

“Well, I suppose—”

“Good man, I knew you would. Can you square Sharples?”

“Fortunately for you, Sharples isn’t playing. If he was, the thing would be off. Sharples wouldn’t spoil his analysis if he were asked to by Royalty. He’s the sort of man who’d send his mother a fast yorker first ball if she batted against him. He has got to go away for the week-end. And Geake can’t play, either. So we are trying a couple of new bowlers.”

“Who are they?”

“Friends of Sharples. Two brothers called Barlow. Sharples says they are useful. Never heard of them myself.”

“Can you square them?”

“I expect so. Any friends of Sharples are bound to be shady. A little thing like this will probably be a pleasant holiday from their regular routine of crime.”

“Well, have a shot at it, there’s a good man. I must rush now. Just got a minute to catch the train. Good-bye.”

“Good-bye.”

“Oh, by the way.”

“Well?”

“Thanks.”

I went back to the smoking-room musing on the follies a man will commit if he is cursed with the obliging nature of a saint. Here was I pledged to induce two perfect strangers to bowl badly before a large audience, possibly to endure ridicule from the same—and for what? To enable a man, for whom they could not be expected to care a dam (a small Javanese coin of inconsiderable value) to become a member of an institution which probably they thoroughly despised. Ah, well, if a man is too good and kind for this world, he must pay the penalty. No doubt I should be rewarded later on. The Guardian Angel must be marking me highly for this. It only remained to carry the thing through.

I wrote to Sharples that night; reminded him of our ancient friendship; enlarged on the desirability of doing Jervis a good turn and thus securing a useful bat and excellent field for our Devonshire tour; and entreated him to do his best to persuade his friends, the bowling brethren, and, finally, to wire to me if all was well.

Two days later I received a telegram from him. “All right” (it ran); “have nobbled Barlows.”

I packed my bag on Friday night with an easy mind.

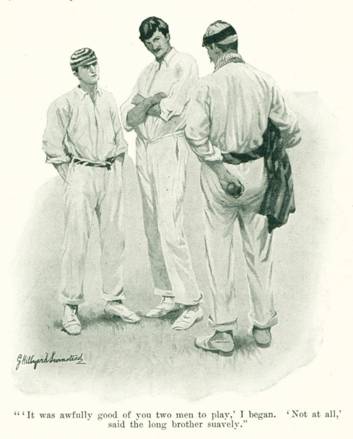

Barlow Brothers consisted of a tall, thin Barlow with a moustache, and a short, thin Barlow without one. They were quiet men, and took no part in the discussion which Gregory, our wicket-keeper, started in the dressing-room on the probability of Tomato beating Toffee-Drop in that afternoon’s race. They also omitted to contribute to a symposium respecting the merits and demerits of the Stapleton ground. Outside, on the field, after I had lost the toss—my invariable custom—I sought them out and addressed them.

“It was awfully good of you two men to play,” I began.

“Not at all,” said the long brother suavely.

“Only too glad of a game,” said the short brother with old-world courtesy.

“Nice day for the match.”

“Capital,” said the long brother.

“Top hole,” said the short brother.

“The election seems to be causing a good deal of excitement down here,” I went on. “Er—by the way, I understand that Sharples has—I mean to say, you’ve grasped the idea? Morley-Davenport, and all that, don’t you know?”

“Sharples explained,” said the clean-shaven Barlow.

“Good,” I said. “Then that’s all right. Of course, don’t overdo it. We must win the match, if possible. Still, if you give him—say twenty-five or thirty, what?”

“Just so,” said the Barlow with the moustache.

“Then will you start at the road end? We’d better be getting out into the field. Their first two men seem to be ready. That stout old chap in the Panama is your man. I asked their captain.”

The candidate took first ball. He had walked to the wickets amidst a perfect storm of cheers and hooting from the large crowd. It seemed to me that the two parties were pretty equally divided. Not being abreast of local politics, I missed a good deal of the inner meaning of such words as I caught. Thus, when a very fat man near the pavilion called out: “What about the gorgonzola?” the question, though well received by the speaker’s immediate neighbours, struck me as cryptic. Nor did I see why a reference to a kipper should elicit such applause. These things were a sealed book to me.

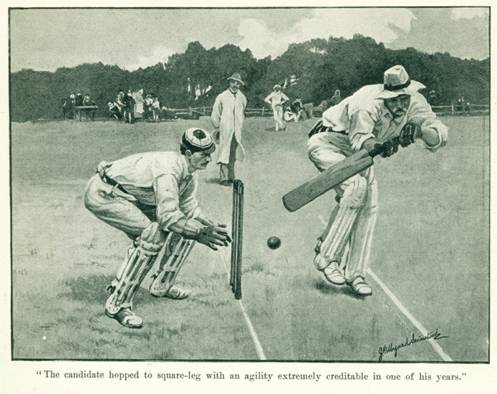

The longer Barlow opened the bowling, as requested. He proved to be a man of speed. He took a very long run, gave a jump in the middle, and hurled down a hurricane delivery wide of the off-stump. He was evidently determined not to let the part he was playing be obvious to the spectator. I was glad of this. I had been afraid that he might roll up stuff of such a kind that the crowd would assail him with yells of derision.

The candidate did not like it at all. He hopped to square-leg with an agility extremely creditable in one of his years. The crowd roared with happy laughter.

“Hide behind the umpire, guv’nor,” advised one light-hearted sportsman.

The rest of the over was a repetition of the first ball. It was a maiden.

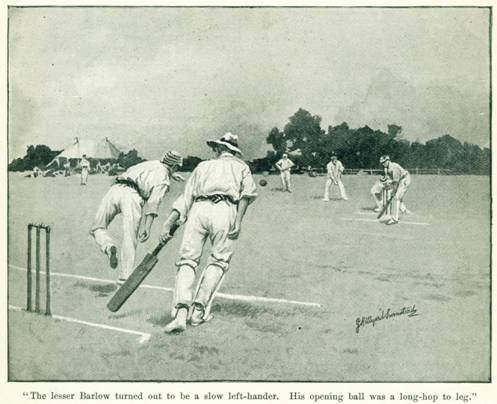

The shorter Barlow wanted two men out on the boundary, from which I deduced that he was a slower bowler than his brother. The batsman who was to receive the ball was a tall, hatchet-faced man of about the same age as Mr. Morley-Davenport. There was a sort of look of the cricketer about him, but he seemed to me rather too much the veteran to be really effective.

The lesser Barlow turned out to be a slow left-hander, and, to judge from his first over, scarcely a Rhodes. His opening ball was a long-hop to leg, and the hatchet-faced man swept it to the boundary. From the roar of applause which ensued I gathered that he was by way of being a local favourite. When he treated the second ball in precisely the same way, I began to be uneasy. If Barlow the lesser bowled like this when he was trying to get a man out, what sort of bilge, if I may be permitted the expression, would he serve up when he was doing his best to let a man make runs? I should have to take him off, in deference to popular indignation, and his successor might—probably would—dismiss our candidate with his first ball.

Fortunately the rest of the over was better. Off the last ball the batsman scored a single, to the huge relief of Mr. Morley-Davenport, who trotted up to the other end evidently delighted at not having to face the fast bowler.

Our man of pace opened with three of his best length ’uns, which the batsman prudently let alone. As I watched him running up to deliver the fourth, my heart sank, for his whole aspect said that here was a man who was going to bowl a slow head-ball. I was fielding mid-on, and I edged apprehensively towards the boundary. Short-leg also looked far from comfortable. Anything more futile than the ball when it did arrive I have seldom seen. It was a full-pitch on the off, and was despatched over point’s head to the ropes, producing fresh applause from the crowd, which was redoubled when the batsman hit a four and a two off the concluding balls.

Some fate seemed to brood over Mr. Morley-Davenport. He slashed valiantly at our slow bowler’s next over without hitting a single ball. I could not say that it was the bowler’s fault. He certainly seemed to be sending down stuff that was sufficiently easy. But the candidate could not get the measure of it, and there were distinct cat-calls from the neighbourhood of the pavilion as the fieldsmen crossed over. The fat critic once more inquired mystically after the gorgonzola.

The game now proceeded in a most unsatisfactory manner. Twenty went up on the board from a snick through the slips on the part of the hatchet-faced man. I had misjudged the beast. He might be a veteran, but he obviously knew how to lay on the wood. He hit a couple of twos off the fast Barlow and a four and a three off the slow Barlow. Thirty went up. Ten minutes later it was followed by forty. And all this while the man Morley-Davenport had not scored a run. He hit over balls and under balls and on each side of balls, and very occasionally he blundered into a ball and sent it to a fieldsman. But never a run did he gather. The situation was becoming feverish. I had not looked for this when Jervis had lured me into becoming his catspaw. Jervis, who was all this while in London, well out of the whole thing!

Matters were growing complicated. The crowd, which had by this time definitely decided to consider the thing funny, laughed heartily whenever Mr. Morley-Davenport let a ball pass him, and applauded thunderously if he happened to hit one. The telegraph-board showed the figures 50. Gloomy discontent had seized the Weary Willies. Changing across between the overs men ostentatiously practised bowling actions, hoping against hope that I would put them on. I could see them becoming misanthropes under my very eyes.

I resolved to abandon Jervis and his schemes. The longer Barlow was just beginning an over. It should be his last. If Morley-Davenport could not score except at the rate of two runs an hour (he had snicked a ball to leg just before the fifty went up, and the crowd had applauded for a solid minute), he must go, and take his chance at the polling.

I had barely framed this ultimatum in my mind when his off-stump flew out of the ground. A fast yorker had compassed his downfall.

“At last!” said mid-off, and flung himself on the ground.

The bowler came over to me.

“I’m very sorry,” he said in his quiet way, “but I thought——”

“Quite right,” I said. “Life’s too short. We should have to run this match as a serial if we wanted that man to get twenty. He wouldn’t do it before the middle of next season. Poor devil, though, it’s rather hard on him. Listen to those fellows!”

The crowd had risen as one man, and was cheering the outgoing batsman as if he had made a century. References to the gorgonzola rose above the din.

“Man in,” said Gregory.

The new batsman took guard.

The disappearance of the candidate seemed to put new life into the Weary Willies. The Barlows, now at liberty to show their true form, worked like professionals. Both were evidently something more than mere club bowlers. I learned later that the fast brother was the J. E. Barlow who had only just missed his Blue at Cambridge in the previous summer.

Three balls were enough for the first-wicket man. A beautifully disguised slow ball beat him all the way, and the last ball of the over accounted for his successor. Fifty for none had become fifty-two for three. The angry passions of the Weary Willies began to subside. A smile creased the face of mid-off, hitherto long and wan.

The slow Barlow got a man stumped in his next over, and the smile became a grin.

With the score at seventy-three for six wickets a prolonged burst of applause announced the completion of the hatchet-faced man’s fifty. All things considered, I suppose, it was a fine effort. But he had certainly had more than his share of loose balls. Every time one of the bowlers sent down a full-pitch to leg, he seemed to be there to receive it.

After the fall of the sixth wicket we struck a stratum of pure rabbits. The last four men failed to score, and the innings closed for eighty-nine. Hatchet Face, who had made sixty-two and carried his bat, received an ovation which eclipsed Mr. Morley-Davenport’s. The Weary Willies joined in the applause. It certainly had been rather a fine performance.

From this point I enjoyed the game thoroughly. I dismissed Jervis from my mind and concentrated myself on my innings. I had been in good form for some time that season, and the Stapleton bowling was poor. I was badly missed by the unhappy candidate when in the twenties, but after that could do nothing wrong. Everything came off for me. We passed their score with only two wickets down, and when stumps were drawn I was not-out a hundred and fifteen. And so home to bed, as Pepys puts it, feeling pleased with life.

I was pained on the Monday evening following the match by a strange post-card from Jervis. The post-card ran as follows: “I knew you would make a mess of it. You’ve settled our hash completely. Read the piece I have marked in the paper I am sending.” I failed to follow him. True, Mr. Morley-Davenport had not had that dazzling success which one could have wished, but nobody could say that I had not done my best for him. It was not my fault if the man could not hit one ball in thirty. I was annoyed with Jervis.

The passage which he had marked in the paper, however, threw a certain amount of light on the matter. Under the heading, “The Stapleton Election,” and the sub-heading, “An Interesting Incident,” there appeared the following paragraph:—

“An amusing by-product of the keenly fought contest at Stapleton took place on Saturday at the New Recreation Grounds, the occasion being the annual match between the town and the Weary Willies Cricket Club. Mr. Morley-Davenport’s partisans had intended to steal a clever march on their opponents by securing for their man a place in the town team—a strategic move which would undoubtedly have gone far towards deciding the result of the polling. At the eleventh hour, however, the secret leaked out, and the opposition camp speedily showed that they too could act. Through the courtesy of the popular and energetic skipper of the town eleven, Mr. Charley Summers, a place was also found in the ranks of the team for Mr. Morley-Davenport’s rival. We need not inform our readers of Mr. Muddock’s prowess on the links, but it was not so generally known that he was as able a wielder of the willow as of the niblick and brassey. His performance on Saturday electrified the large and enthusiastic crowd which had assembled to witness the match. With a true eye for the dramatic, Mr. Summers sent the two rivals in together to open the batting for their side. The comparison between the two ‘gave furiously to think.’ While Mr. Muddock hit the bowling to all corners of the field without once appearing to be in difficulties, Mr. Morley-Davenport proved that his cricket is as feeble and vacillating, as futile and ludicrous as are his politics. There was something painful . . . . For more than an hour . . . . finally dismissed for the majestic score of two runs. Mr. Muddock, on the other hand . . . . vigorous display . . . . forceful tactics . . . . In short . . . .”

A week later the papers were announcing that Mr. T. Muddock, the new M.P. for Stapleton, “yesterday took his seat for the first time in the House, being warmly cheered by the members of his party as he entered.”

A paragraph that appeared in one of the Society weeklies at about the same time had a special interest for me. “A marriage has been arranged,” said the paragraph, “and will shortly take place, between John Edwin, eldest son of George Albamont Barlow, of The Mote, Shrewsbury, and Alice Catherine Maud, only daughter of Thomas Muddock, M.P., The Manor, Stapleton. Mr. Barlow,” continued the writer, “is a keen cricketer, and narrowly missed playing for Cambridge at Lord’s last season.”

Jervis, who has declined to join the Weary Willies on their Devonshire tour, still sticks to it that the whole thing was my fault. Well—I mean—what can you do with a man like that?

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums