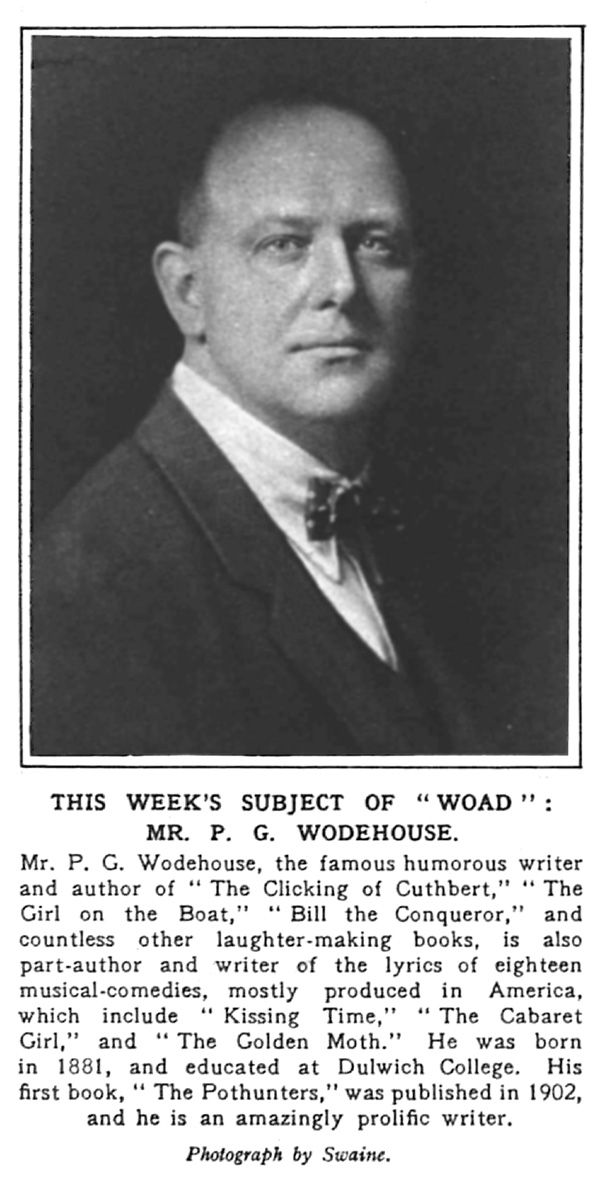

The Sketch (UK), June 16, 1926

“ THAT monkey,” said Mr. P. G. Wodehouse, in a firm and dispassionate voice, “is wearing its club colours in the wrong place.”

It was. The animal in question was a vast and obscene form of mandrill called George, which darted shamelessly in and out of its cage, snorted, turned its terrible multi-coloured back upon an outraged populace, and departed again, leaving everybody a little breathless and pale, and talking hurriedly about moving on to see the lions.

But P. G. Wodehouse did not hurry on to see the lions. Perhaps he was too fascinated by the reactions caused by George’s anatomy upon the sedate families whom fate lured towards his cage. What were these families to say? George was evidently the work of God. But he was even more evidently obscene. How to reconcile these two distressing facts, especially when the originator of the problem was flaunting its provocation in one’s face? I do not know the answer. But perhaps P. G. Wodehouse one day will, through the medium of laughter, give it to us.

And here, right at the beginning, I must warn you that this is to be no recital of Wodehouse epigrams on the subject of animals. He made none. He merely gazed mildly through his glasses at all the specimens of beasts that came his way, offering them, throughout the course of an entire afternoon, the wrong sort of food, which, to his increasing pain, they rejected. But if you insist on knowing what he said, I can write it in a few lines.

1. Concerning the turtle, he observed its resemblance to Mr. Leslie Henson.

2. Concerning the elephants, he noted that they appeared to be fully developed, both muscularly and aromatically.

3. Concerning the octopuses, he remarked that he would be pleased to see a beauty chorus of these monsters.

Apart from that, he grew increasingly sombre and preoccupied. Perhaps that was because he could not find the snakes (for which he seemed to cherish an unnatural affection). Whenever there was a pause in the conversation, he said, rather plaintively, “I suppose there are snakes?”—and the rest of us, who did not at all wish to see the snakes, remarked quickly that of course there were snakes, lots of them, but that they were a long way off, and just look at that lovely antelope. He looked, sighed, and said “Yes, it is a beautiful antelope.” But one knew that in his heart of hearts he cherished a fierce resentment against that antelope, simply because it was not a snake.

. . . . .

How dreadful it must be to have the reputation of a great humorist. I am sure that Wodehouse feels it. When I first met him, we were both lunching at the House of Commons, and I noted that whenever he opened his mouth the faces of the politicians seated round him prepared to twitch up into set smiles. They were saying to themselves, “Now he’s going to begin.” And when he did not begin, but behaved like an ordinary human being (although his conversation was more coloured and alive than that of most of us), they were quite disappointed. They looked as though they had been cheated—the brutes. I fail to see why. After all, even if he does not make jokes, he is excellent company, and he radiates charm. Best of all, he never talks about himself. If you wish to learn anything about “Plum” (as I really cannot help calling him), you must learn it from his wife. And here, jotted down at random, are some of the things that one learns. . . .

The Wodehouse Glide. This refers, not to his prowess as a dancer, but to his almost uncanny capacity for disappearances. Whenever he finds himself at a party where the ground is a little too thick with millionaires, or where too many peeresses are calling to their young, or where the wits are warbling too shrilly, he disappears. There is no other word for it. At one moment he is there. At the next moment he is gone. Many legends have been invented to account for this capacity. Some say that he slides down the banisters. Others affirm that he carries a drooping moustache in his pocket, which he affixes while blowing his nose. I have even heard it suggested that he secretes himself behind a curtain and makes a burglarious exit down the drain-pipe. Whatever his method, he disappears.

These disappearances are really the key to his character, which is dominated by a loathing for display. They enable one to understand the next mystery about him, which may be described under the heading of—

Saturday Afternoons. Every Saturday afternoon, Mr. P. G. Wodehouse disappears. For many years the reasons why he went, where he went, and what he did when he got there, were insoluble problems to his family. But they never inquired. There was a tacit understanding that they should not do so. He simply departed into space.

I am able, from a secret source, to throw light upon the problem of Mr. Wodehouse’s Saturday afternoons, and I give the information with a strict sense of my responsibility to the future literary historian. He goes to a football match. There. It is out. Please do not follow him there. He does not want you at all. He wants to pay his sixpence, or whatever fee they charge one at these functions, and to enjoy the supreme English pleasure of standing in an icy wind watching a number of young men scramble about in the mud, while hoarse men breathe down his neck. I would give my soul to be able to like that sort of thing, because I cannot imagine a cheaper pleasure, nor one which so quickly sets one in tune with the rest of mankind. But I cannot.

The next fragment may be labelled—

The Simple Life. This is best illustrated by a brief anecdote. Before Plum was married, he lived in the country, working. One day a sumptuous gentleman called upon him to indicate that for a trifling fee he would confer upon him the benefits of insurance. Plum said that he would be delighted to receive, and pay for, this benefit, and would the sumptuous gentleman accept a cigarette? He accepted a cigarette, and as he lit it, he remarked—

“I see you are just on the point of moving into this house. Where was your home before?”’

Plum gazed at him blankly. “Moving in?” he said. “What do you mean?”

The shadowy suggestion of a bum bailiff must have danced through the sumptuous one’s mind, for he answered, a little tersely: “Well, look at this room.”

Plum looked at it. He saw a table and two deck chairs. Nothing else. He suddenly realised his shortcomings. It was an empty house, a house which would have caused Mr. Drage to rub his hands and grow lyrical over the prospect of men laying “lino” (what is “lino,” by the way?) free of charge. An empty house! Oh, Plum! Perhaps it was the company of your twelve dogs that had made you forget its emptiness for three whole years? At any rate, I understand that the sumptuous one departed in a huff.

Equally simple are his clothes. For the past two years there have been reposing at a famous tailor’s shop two suits of clothes marked “Wodehouse.” One of them, in shape and colour, suggests Ascot. The other, by its rich blue and chic cut, indicates that one is meant to lounge in it. But Plum has neither strutted in the one nor lounged in the other. New clothes are a torture to him. Many men say that and do not mean it, taking a secret and unholy pleasure in preening themselves before those fascinating triple mirrors which do such funny things to one’s profile. But Plum really does mean it. Only some serious crisis will ever make him enter that tailor’s shop again.

Notes:

Beverley Nichols (1898–1983) was an English writer, critic, and playwright, noted as one of the “bright young things” of the 1920s. His early book Twenty-Five (1926) was favorably reviewed by Wodehouse, and that led to the interview reflected in the present article. Nichols expanded these biographical articles into a 1927 book titled Are They the Same at Home? (scan at Internet Archive, cued to the Wodehouse chapter). Barry Phelps in P. G. Wodehouse: Man and Myth and Robert McCrum in Wodehouse: A Life drew on this latter article to describe the relationship between Wodehouse and Nichols.

Printer’s error corrected above:

Magazine had “as he lit he, he remarked”; corrected to match book appearance.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums