The Captain, February 1913

CHAPTER VI

the disappearance of ogden

THE armchair critic, reviewing a situation calmly and at his ease, is apt to make too small allowance for the effect of hurry and excitement on the human mind. I had lost my head, and had ceased for the moment to be a reasoning creature. In the end, indeed, it was no presence of mind but pure good luck which saved me. Just as the door, which had held out gallantly, gave way beneath the attack from outside, my fingers, slipping, struck against the catch of the window, and I understood why I had failed to raise it.

I snapped the catch back, and flung up the sash. An icy wind swept into the room, bearing particles of snow. I scrambled on to the window-sill, and a crash from behind me told of the falling of the door.

The packed snow on the sill was drenching my knees as I worked my way out and prepared to drop. There was a deafening explosion inside the room, and simultaneously something seared my shoulders like a hot iron. I cried out with the pain of it, and, losing my balance, fell from the sill.

There was, fortunately for me, a laurel-bush immediately below the window. I fell into it, all arms and legs. I was on my feet in an instant. The idea of flight, which had obsessed me a moment before to the exclusion of all other mundane affairs, had vanished absolutely. I was full of fight—I might say overflowing with it. I remember standing there with the snow trickling in chilly rivulets down my face and neck, and shaking my fist at the window. Two of my pursuers were leaning out of it, while a third dodged about behind them, like a small man on the outskirts of a crowd. So far from being thankful for my escape, I was conscious only of a feeling of regret that there was no immediate way of getting at them.

From the direction of the front door came the sound of one running. A sudden diminution of the noise of his feet told me that he had left the gravel and was on the turf. I drew back a pace or two and waited.

It was pitch dark, and I had no fear that I should be seen. I was standing well outside the light from the window.

The man stopped just in front of me. A short parley followed.

“Can’tja see him?”

The voice was not Buck’s. It was Buck who answered. And when I realised that this man in front of me, within easy reach, on whose back I was shortly about to spring, and whose neck I proposed, under Providence, to twist into the shape of a corkscrew, was no mere underling but Mr. Macginnis himself, I was filled with a joy which I found it hard to contain in silence.

Looking back, I am a little sorry for Mr. Macginnis. He was not a good man. His mode of speech was not pleasant, and his manners were worse than his speech. But, though he undoubtedly deserved all that was coming to him, it was nevertheless bad luck for him to be standing there at just that moment.

He had got as far, in his reply, as “Naw, I can’t——” when I sprang. I connected with Mr. Macginnis in the region of the waist, and we crashed to the ground together.

Our pleasures are never perfect. There is always something. In the programme which I had hastily mapped out, the upsetting of Mr. Macginnis was but a small item, a mere preliminary.

There were a number of things which I had wished to do to him, once upset. But it was not to be. A compact form was already wriggling out on the window-sill, as I had done, and I heard the grating of his shoes on the wall as he lowered himself for the drop.

There is a moment when the pleasantest functions must come to an end. I was loth to part from Mr. Macginnis just when I was beginning, as it were, to do myself justice; but it was unavoidable.

I disengaged myself—Mr. Macginnis strangely quiescent during the process—and was on my feet in the safety of the darkness just as the reinforcement touched earth. This time I did not wait. My hunger for fight had been appeased to some extent by my brush with Buck, and I was satisfied to have achieved safety with honour.

Making a wide detour, I crossed the drive and worked my way through the bushes to within a few yards of where the automobile stood, filling the night with the soft purring of its engines.

I had not been watching long before a little group advanced into the light of the automobile’s lamps. There were four of them. Three were walking; the fourth was lying on their arms, of which they made something resembling a stretcher.

The driver of the car, who had been sitting woodenly in his seat, turned at the sound.

“Ja get him?” he inquired.

“Get nothing!” replied one of the three moodily. “De kid ain’t dere, an’ we was chasin’ Sam to fix him, an’ he laid for us, an’ what he did to Buck was plenty.”

They placed their burden in the tonneau, where he lay repeating himself, and two of them climbed in after him. The third seated himself beside the driver.

“Buck’s leg’s broke,” he announced.

No young actor, receiving his first round of applause, could have felt a keener thrill of gratification than I did at these words. Life may have nobler triumphs than the breaking of a kidnapper’s leg, but I did not think so then. It was with an effort that I stopped myself from cheering.

The car turned and began to move with increasing speed down the drive. Its drone grew fainter and ceased. I brushed the snow from my coat, and walked to the front door.

My first act, on entering the house, was to release White. He was still lying where I had seen him last. He appeared to have made no headway with the cords on his wrists and ankles. I came to his help with a rather blunt pocket-knife, and he rose stiffly and began to chafe the injured arms in silence.

“They’ve gone,” I said.

He nodded.

“I broke Buck’s leg,” I said, with modest pride.

He looked up incredulously. The gloom was swept from his face by a joyful smile. Buck’s injury may have given its recipient pain, but it was certainly the cause of pleasure to others.

I had been vaguely conscious during this conversation of an intermittent noise like distant thunder. I now perceived that it came from Glossop’s class-room, and was caused by the beating of hands on the door-panels. I remembered that the red-moustached man had locked Glossop and his young charges in. I unlocked the door and the class-room, its occupants, headed by my colleague, disgorged in a turbulent stream. At the same moment my own class-room began to empty itself. The hall was packed with boys, and the din became deafening. Everyone had something to say, and they all said it at once.

Glossop’s eyes gleamed agitatedly. Macbeth’s deportment, when confronted with Banquo’s ghost, was stolid by comparison. There was no doubt that Buck’s visit had upset the smooth peace of our happy little community to quite a considerable extent.

Small boys are always prone to make a noise, even without provocation. When they get a genuine excuse like the incursion of men in white masks, who prod assistant masters in the small of the back with Browning pistols, they tend to eclipse themselves. I doubt whether we should ever have quieted them, had it not been that the hour of Buck’s visit had chanced to fall within a short time of that set apart for the boys’ tea, and that the kitchen had lain outside the sphere of our visitors’ operations. As in many English country houses, the kitchen at Sanstead House was at the end of a long corridor, shut off by doors through which even pistol-shots penetrated but faintly. The cook had, moreover, the misfortune to be somewhat deaf, with the result that, throughout all the storm and stress in our part of the house, she, like the lady in Goethe’s poem, had gone on cutting bread and butter; till now, when it seemed that nothing could quell the uproar, there rose above it the ringing of the bell.

If there is anything exciting enough to keep the Englishman or the English boy from his tea, it has yet to be discovered. The shouting ceased on the instant. The general feeling seemed to be that inquiries could be postponed till a more suitable occasion, but not tea. There was a general movement in the direction of the dining-room.

I left Glossop to preside at the meal, and went upstairs to see Mr. Abney. It seemed to me that something in the nature of an official report ought to be made to him. It was his school that Mr. Macginnis and his friends had been kicking to pieces.

My tap upon his door produced an agitated “Who’s that?” I reassured him, and there came from within the sound of moving furniture. His one brief interview with Buck had evidently caused my employer to ensure against a second by barricading himself in with everything he could lay his hands on.

“Cub id,” said a voice at last. Mr. Abney was sitting up in bed, the blankets wrapped tightly about him. His appearance was still disordered. The furniture of the room was in great confusion, and a poker on the floor by the dressing-table showed that he had been prepared to sell his life dearly.

“Bister Burds,” he said, “what is the explanation of this extraordinary affair?”

“It was a gang of American kidnappers. They were after Ogden Ford. White tells me they have been after him for some time.”

“White?” said Mr. Abney, puzzled.

It struck me that the time had come to reveal White’s secret. Certainly the motive for concealing it—the fear of making Mr. Abney nervous—was removed. An inrush of Red Indians with tomahawks could hardly have added greatly to Mr. Abney’s nervousness just at present.

“White is a detective,” I said.

It took some time to make the matter thoroughly clear to Mr. Abney, but I had just done so when Glossop whirled into the room.

“Mr. Abney, Ogden Ford is nowhere to be found!”

Mr. Abney greeted the information with a prodigious sneeze.

“What do you bead?” he demanded, when the paroxysm was over. He turned to me. “Bister Burds, I understood you to—ah—say that the scou’drels took their departure without him?”

“They certainly did. I watched them go.”

“I have searched the house thoroughly,” said Glossop, “and there are no signs of him. And not only that—the boy Beckford cannot be found.”

Mr. Abney clasped his head in his hands. Poor man, he was in no condition to bear up with easy fortitude against this succession of shocks. He was like one who, having survived an earthquake, is hit by an automobile. He had partly adjusted his mind to the quiet contemplation of Mr. Macginnis and friends, when he was called upon to face this fresh disaster. And he had a cold in the head, which unmans the stoutest. Napoleon would have won Waterloo if Wellington had had a cold in his head.

“The boy Beckford caddot be fou’d!” he echoed, feebly.

“They must have run away together,” said Glossop.

Mr. Abney sat up, galvanised.

“Such a thi’g has dever happ’n’d id the school before!” he cried. “I caddot seriously credit the fact that Augustus Beckford, one of the bost charbi’g boys it has ever beed my good fortude to have id by charge, has deliberately rud away.”

“He must have been persuaded by that boy Ford,” said Glossop.

“Subthi’g bust be done at once,” Mr. Abney exclaimed. “It is ibperative that we take ibbediate steps. They bust have gone to London.” An idea struck him. “Bister Burds, tell White I wish to speak to him. Bister Glossop, I think you had better go back to the boys now. Please find White at once, Bister Burds.”

I found White in the hall, and explained matters to him.

“Mr. Abney wants to see you,” I said. “Ogden Ford has run away to London, and I think he wants you to go after him. I have told him who you are and why you are here. I hope you don’t mind?”

“Not at all. I should have told him myself in any case, now that the necessity has arisen.”

We went upstairs. Mr. Abney was sitting up in bed, waiting for us.

“Cub id, White,” he said. “Bister Burds has just bade an—ah—extraordinary cobbudication to me. It seebs you are a—id fact—a detective.”

“Yes, sir,” said White.

“Sent here by Bister Ford?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Exactly. Ah—precisely.” He sneezed. “I do not cobbedt on the good taste or wisdob of Bister Ford’s actiod id keeping the matter a secret and not i’forbing me. All that is beside the point. Ogden Ford and Augustus Beckford have rud away to Londod. I wish you, White, to follow them. I should be glad if you would accompady White, Bister Burds!”

“I don’t think it necessary to trouble Mr. Burns,” said White. “I am sure I can manage by myself.”

“Two heads are better than wud.”

“Too many cooks spoil the broth, sir.”

“Dodseds,” said Mr. Abney irritably, ending this interchange of proverbial wisdom with a sneeze. “Bister Burds will accompady you, as I say.”

“Very well, sir.”

And we left the room, to look out a train.

CHAPTER VII

smooth sam fisher

AS my first essay in detective work, I could have wished that the tracking down of Ogden Ford and his friend Augustus had been more of a feat, but I am bound to admit that it was a singularly soft job. Dr. Watson could have done it on his head. Even what little credit there was attached to the performance was not mine. It was White who made the suggestion that led to our success—namely, that we should find out the address of young Beckford’s parents, and make inquiries there. We could not apply to Mr. Elmer Ford, he, White informed me, having returned to America.

I did not know the Beckfords’ address, and it was too late to telegraph for it that night. I did so the next morning, and received the answer towards the middle of the afternoon. Augustus’s mother lived in Eaton Square.

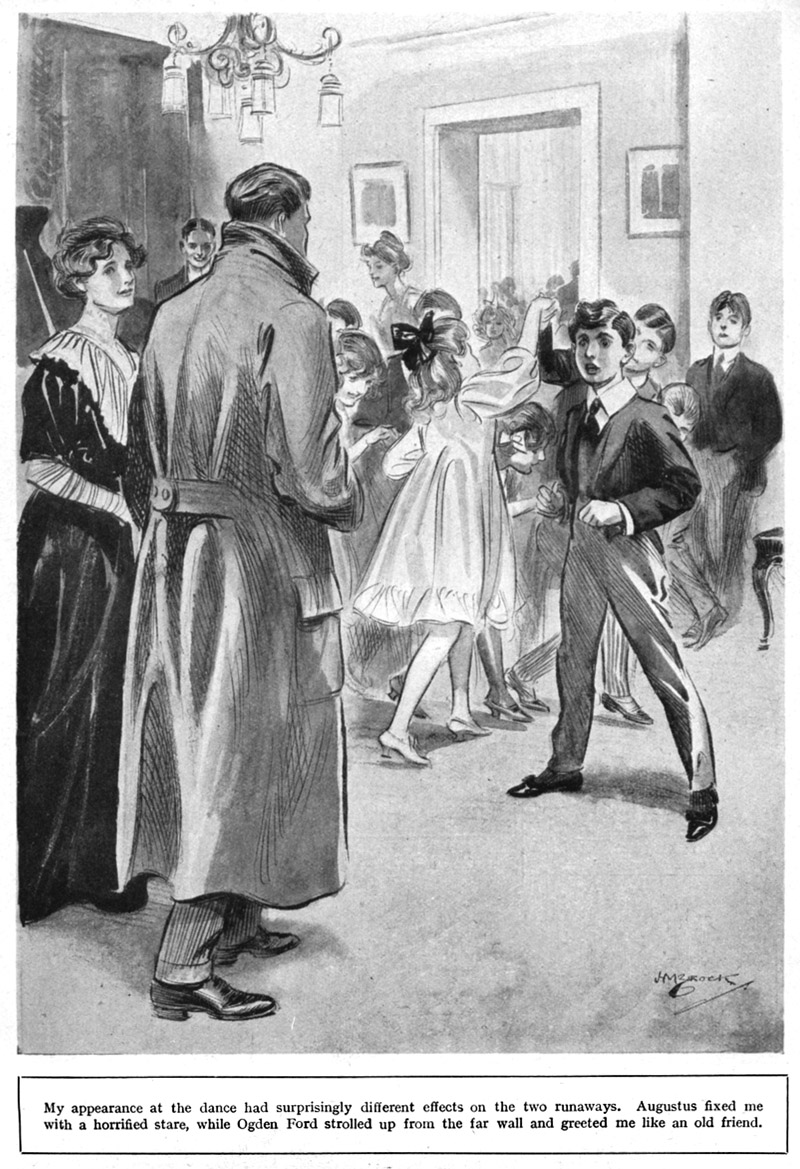

When we arrived there, shortly after four, the mystery of Augustus’s departure from the spot which it had been Mr. Abney’s constant endeavour to make him regard as a happy home was explained. Sounds of revelry from within greeted us on the doorstep. There was a children’s party going on.

Mrs. Beckford received me warmly. I had explained, when giving my name to the butler, that I was from the school. White preferred to wait in the square during the interview.

“It was so kind of Mr. Abney to let Augustus come up for his sister’s birthday and bring his friend with him,” she said. “I did not like to ask him, but Augustus seems to have managed it all on his own account.”

I respected Augustus’s secret. It did not seem to me that there was anything to be gained by exposing him in the home circle. So long as I took him back, I had done my part.

“I happened to be coming to London to-day,” I said, “so Mr. Abney asked me to bring Augustus and Ogden Ford back with me. I thought of catching the seven o’clock train. May I see Augustus for a moment?”

Mrs. Beckford led me to the drawing-room. Some sort of dance was going on. There was Augustus, his face shining with honest joy, leading the revels, while against the far wall, wearing the blasé air of one for whom custom has staled the more obvious pleasures of life, leaned Ogden Ford.

The effect of my appearance on them was illustrative of their respective characters. Augustus turned bright purple, and fixed me with a horrified stare. Ogden winked.

The dance came to an end. Augustus stood goggling at me and shuffling his feet. Ogden strolled up and accosted me like an old friend.

“Hello!” he said. “I was wondering if you or the hot-air merchant would blow in. Come to fetch us back?”

He looked kindly over his shoulder at Augustus.

“Better let him enjoy himself while he’s here. There’s no hurry, I guess, now you’ve found us; and he likes this sort of thing. As a matter of fact, we were coming back to-night in any case. I shan’t be sorry. I wanted to see what this sort of thing was like over here in England, but I’m sorry I came now—I’m bored pallid. Couldn’t we slip away somewhere? Got a cigarette?”

The airy way in which this demon boy handled what should have been—to him—an embarrassing situation irritated me. For all the effect my presence had on him, I might have been the potted palm against which he was leaning.

“I have not got a cigarette,” I said.

He regarded me tolerantly.

“Got a grouch this evening, haven’t you? You seem all worked up about something.” His face lighted up. He produced from his pocket a crumpled, battered-looking cigarette. “Thought I hadn’t one left,” he said, happily. “I’d forgotten this. Well, see you later.”

He disappeared, leaving me to find my way out and report to White.

White was walking up and down the pavement.

“It’s all right,” I said. “They’re in there.”

“Both of them?”

“Yes.”

White expelled what seemed to be a breath of relief. I began to notice something strange in his manner—a suppressed excitement foreign to his usual stolid calm.

“Mr. Burns,” he said, “let’s get where we can talk. I’ve got something I want to say to you. I’ve got a proposition to make.”

I looked at him in surprise. Could this be White, of the rich voice and the measured speech? It was a stranger speaking—a brisk, purposeful stranger, with a marked American intonation.

“See here,” he said; “we must get together over this business.”

Perhaps it was the recollection of the same words in the mouth of Buck Macginnis that startled me. His eyes were gleaming with excitement, and he gripped my arm.

“Say, it’s the chance of a lifetime,” he went on. “Here’s the kid up in London, and nobody knows where except you and me. If ever there was a case of fifty-fifty, this is it. I can’t get away with him without your help, and it’s the same with you. The only thing is to sit in at the game together and share out. Does it go? Think quick!” he said. “I guess this comes as a kind of surprise to you, but hustle your brain and get a hold on it. Maybe you never thought of anything like this before, but surely to goodness you can see now what a gilt-edged chance it is.”

He met my bewildered gaze, and calmed down. He chuckled.

“I ought to have started by explaining,” he said. “I guess this seems funny talk to you from a detective. I’m not a detective, sonny. You caught me with a gun in the school grounds, so I had to put up some tale. I’m no sleuth, though—take it from me. Do you remember my telling you of a fellow named Smooth Sam Fisher? I’m Sam.”

CHAPTER VIII

i decline a business offer

“SMOOTH SAM FISHER!” I gaped at him. He nodded.

“It’s always been a habit of mine in these little matters,” he went on, “to let other folks do the rough work, and chip in myself when they’ve cleared the way. It saves trouble and expense. I don’t travel with a gang, like that bone-head Buck. What’s the use of a gang? They only get tumbling over each other and spoiling everything. Look at Buck! Where is he? Down and out. While I——”

He smiled complacently. His manner annoyed me. I had adjusted my mind to the fact of his identity now, and I objected to his bland assumption that I was his accomplice.

“While you—what?” I said.

He looked at me in mild surprise.

“Why, I come in with you, sonny, and take my share like a gentleman.”

“Do you!”

“Well, don’t I?”

He looked at me in the half reproachful, half affectionate manner of the kind old uncle who reasons with a headstrong nephew.

“Young man,” he said, “you surely aren’t thinking you can put one over on me in this business? Tell me, you don’t take me for that sort of ivory-skulled boob! Do you imagine for one instant, sonny, that I’m not next to every move in this game? Let’s hear what’s troubling you. You seem to have gotten some foolish ideas in your head. Let’s talk it over quietly.”

“If you have no objection—no,” I said. “I don’t want to talk to you, Mr. Fisher.”

He looked at me shrewdly. Apparently I had not offended him, only made him cautious.

“The present arrangement of equal division,” he said, “holds good, of course, only in the event of your doing the square thing by me. Let me put it plainly. We are either partners or competitors. I have given you the idea of taking this chance of kidnapping the Ford kid, and you may think you can do it without any help. Don’t try it! Young man, I am nearly twice your age, and I have, at a modest estimate, about ten times as much worldly wisdom. And I say to you, don’t miss this chance. You will be sorry if you do, believe me! Later on, when I am a rich man and my automobile splashes you with mud in Piccadilly, you will taste the full bitterness of remorse.”

I looked at him as he stood, plump and rosy and complacent, puffing at his cigarette, and my heart warmed to the old ruffian. It was impossible to be angry with him. I might hate him as a representative—and a leading representative—of one of the most contemptible trades on earth, but there was a sunny charm about the man himself which made it hard to feel hostile to him as an individual.

I burst out laughing.

“You’re a wonder!” I said.

He beamed.

“Then you think, on consideration——?” he said. “Excellent! We are partners! We will work this together. All I ask is that you rely on my wider experience of this sort of game to get the kid safely away and open negotiations with papa.”

“I suppose your experience has been wide?” I said.

“Quite tolerably. Quite tolerably.”

“Doesn’t it ever worry you, the anxiety and misery you cause?”

“Purely temporary, both. And then look at it in another way. In a sense you might call me a human benefactor. I teach parents to appreciate their children. You know what parents are. Father loses a block of money in the City. When he reaches home, what does he do? He eases his mind by snapping at little Willie. Mother’s new dress doesn’t fit. What happens? Mother takes it out of William. And then one afternoon he disappears. The agony! The remorse! ‘How could I ever have told our lost angel to stop his darned noise!’ moans father. ‘I struck him!’ sobs mother. ‘With this jewelled hand I spanked our vanished darling!’ ‘We were not worthy to have him!’ they wail together. ‘But oh, if we could but get him back!’ Well, they do. They get him back as soon as ever they care to come across in unmarked hundred-dollar bills. And after that they think twice before working off their grouches on the poor kid. So I bring universal happiness into the home. I don’t say father doesn’t get a twinge every now and then when he catches sight of the hole in his bank balance, but, hang it, what’s money for if it’s not to spend?”

He snorted with altruistic fervour.

“What makes you so set on kidnapping Ogden Ford?” I asked. “I know he is valuable, but you must have made your pile by this time. I gather that you have been practising your particular brand of philanthropy for a good many years. Why don’t you retire?”

He sighed.

“It is the dream of my life to retire, young man. You may not believe me, but my instincts are thoroughly domestic. When I have the leisure to weave day-dreams, they centre around a cosy little home with a nice porch and stationary wash-tubs.”

He regarded me closely, as if to decide whether I was worthy of these confidences. There was something wistful in his brown eyes. I suppose the inspection must have been favourable, as he was in a mood when a man must unbosom himself to someone, for he proceeded to open his heart to me. A man in his particular line of business, I imagine, finds few confidants, and the strain probably becomes intolerable at times.

“Have you ever experienced the love of a good woman, sonny? It’s a wonderful thing.” He brooded sentimentally for a moment, then continued, and—to my mind—somewhat spoiled the impressiveness of his opening words. “The love of a good woman,” he said, “is about the darnedest wonderful lay-out that ever came down the pike. I know. I’ve had some.”

A spark from his cigarette fell on his hand. He swore a startled oath.

“We came from the same old town,” he resumed, having recovered from this interlude. “Used to be kids at the same school. Walk to school together. Me carrying her luncheon-basket, and helping her over the fences. Ah! Just the same when we grew up. Still pals. And that was twenty years ago. The arrangement was that I should go out and make the money to buy the home, and then come back and marry her.”

“Then why in the world haven’t you done it?” I said, severely.

He shook his head.

“If you know anything about crooks, young man,” he said, “you’ll know that outside of their own line they are the easiest marks that ever happened. They fall for anything. At least, it’s always been that way with me. No sooner did I get together a sort of pile and start out for the old town, when some smooth stranger would come along and steer me up against some skin-game, and back I’d have to go to work. That happened a few times, and when I did manage at last to get home with the dough, I found she had married another guy. It’s hard on women, you see,” he explained, chivalrously. “They get lonesome, and Roving Rupert doesn’t show up, so they have to marry Stay-at-home Henry just to keep from getting the horrors.”

“So she’s Mrs. Stay-at-home Henry now?” I said, sympathetically.

“She was till a year ago. She’s a widow now. I saw her just before I left to come here. She’s as fond of me as ever. It’s all settled, if only I can get the money. And she don’t want much either. Just enough to keep the home together.”

“I wish you happiness,” I said. “What does she say to your way of making money?”

“She don’t know. And she ain’t going to know. I don’t see why a man has got to tell his wife every little thing in his past. She thinks I’m a commercial traveller, travelling in England for a dry-goods firm. She’s very particular—always was. That’s why I’m going to quit after I’ve won out over this business. And now that you are standing in——”

I shook my head.

“You won’t?”

“I’m sorry to spoil a romance, but I can’t. You must look around for some other home into which to bring happiness. The Fords’ is barred.”

“You are very obstinate, young man,” he said sadly, but without any apparent ill-feeling. “I can’t persuade you?”

“No.”

“Ah, well! So we are to be rivals, not allies. You will regret this, sonny. I may say you will regret it very bitterly. When you see me in my automo——”

“You mentioned your automobile before.”

“Ah! So I did.”

He drew at his cigarette thoughtfully.

“I don’t understand you, young man. I don’t know how much salary you get at the school, but I guess it’s not particularly much. And there’s no knowing what old man Ford wouldn’t cough up, if you’d only stand in with me and leave me to work the negotiations. Yet you won’t come in with me on this thing. Why?—that’s what beats me. Why?”

“Call it conscience. If you know what that means.”

“And you are really going to take him back to the school?”

“I am.”

“Well, well,” he sighed. “I hoped I had seen the last of the place. The English countryside may be delightful in the summer, but for winter give me London. However”—he sighed again resignedly—“shall we travel down together? What train did you think of taking?”

“Do you mean to say,” I demanded, “that you have the cheek, the nerve, to come back to the school after what you have told me about yourself?”

“Did you think of exposing me to Mr. Abney? Forget it, young man. He would not believe you.”

“It won’t be hard to prove. All he will have to do will be to ask Mr. Ford if he did send a detective to Sanstead.”

“Mr. Ford is in America.”

“There is the cable.”

“Don’t try it. You would only waste your money. Mr. Ford’s answer would be that he did send a detective. He was a man of the name of Dennis. A very intelligent man. It cost me a great deal of money—most of it, I admit, in promises—to induce him to throw up the job and stand in with me. How’s Mr. Ford to know that I am not the man he sent? No, I think you will see, sonny, that you will not gain much by informing Mr. Abney. So to-morrow, after our little jaunt to London, we shall all resume the quiet rural life once more.”

He beamed expansively upon me.

“However, even the quiet, rural life has its interests. I guess we shan’t be dull.”

I believed him.

CHAPTER IX

coffee, and an announcement

CONSIDERING the various handicaps under which he laboured—notably a cold in the head and a fear of Ogden—Mr. Abney’s handling of the situation, when the runaways returned to the school, bordered on the masterly. Having conscientious objections to corporal punishment, he fell back on oratory, and he did this to such effect that, when he had finished, Augustus Beckford wept openly, and was so subdued that he hardly spoke for days.

One result of the adventure was that Ogden’s bed was moved to a sort of cubby-hole adjoining my room. In the house as originally planned, this had evidently been a dressing-room. Under Mr. Abney’s rule it had come to be used as a general repository for lumber. My boxes were there, and a portmanteau of Glossop’s. It was an excellent place in which to bestow a boy in quest of whom kidnappers might break in by night. The window was too small to allow a man to pass through, and the only means of entrance was by way of my room. By night, at any rate, Ogden’s safety seemed to be assured.

The curiosity of the small boy, fortunately, is not lasting. His active mind lives mainly in the present. It was not many days, therefore, before the excitement caused by Buck’s raid and Ogden’s disappearance began to subside. Within a week both episodes had been shelved as subjects of conversation, and the school had settled down to its normal humdrum life.

In the days which followed, the behaviour of Smooth Sam Fisher puzzled me. I do not know just what I expected him to do, but I certainly did not expect him to do nothing. Yet time went on, and still he made no move. It was only by reminding myself constantly that he was a man who believed in waiting his opportunity that I kept myself from relaxing my vigilance.

He was a fine actor. He knew that I was watching him, and he knew that I was aware of this; yet never once, by so much as a look, did he abandon the rôle he had set himself to play. He was the very model of a butler. When he spoke to me, the grave respect which he put into his voice at times almost set me off my guard. I think that if I had had the information that he was a kidnapper from any other lips than his own, I should have been unable to believe it. But our dealings with one another in London had left me vigilant, and his pose did not disarm me. His inaction sprang from patience: it was not due to any weakening of purpose or despair of success. Sooner or later, I knew, he would act swiftly and suddenly, with a plan perfected in every detail.

I was right. But when he made his attack, it was the very simplicity of his methods that tricked me; and, but for a lucky chance, which no strategist could have foreseen and guarded against, I should have been defeated.

I have said that it was the custom of the staff of masters at Sanstead House School—in other words, of every male adult in the house except Mr. Fisher himself—to assemble in Mr. Abney’s study after dinner of an evening to drink coffee. It was a ceremony—like most of the ceremonies at an establishment such as a school, where things are run on a schedule—which knew of no variation. Sometimes Mr. Abney would leave us immediately after the ceremony, but he never omitted to take his part in it first.

On this particular evening, for the first time since the beginning of the term, I was seized with a prejudice against coffee. I had been sleeping badly for several nights, and, searching for a remedy, I decided that abstention from coffee might help me.

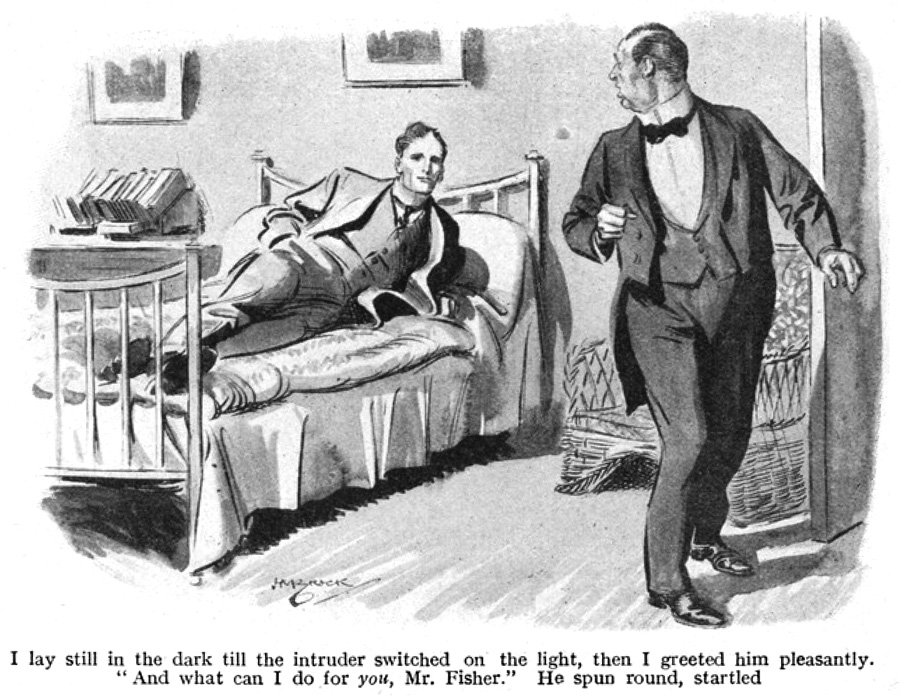

I waited, for form’s sake, till Glossop and Mr. Abney had filled their cups, then went to my room, where I lay down in the dark. From the room beyond came faintly the snores of the sleeping Ogden.

At this moment Smooth Sam Fisher had no place in my meditations. My mind was not occupied with him at all. When, therefore, the door, which had been ajar, began to open slowly, I did not become instantly on the alert, I attributed the movement to natural causes, and wondered if it were worth while getting up to shut it.

The opening widened.

Perhaps it was some sound, barely audible, that aroused me from my torpor and set my blood tingling with anticipation. Perhaps it was the way the door was opening. An honest draught does not move a door furtively in jerks.

I sat up noiselessly, tense and alert. And then, very quietly, somebody entered the room.

There was only one man in Sanstead House who would enter a room like that. I was amused. The impudence of the thing tickled me. It seemed so foreign to Mr. Fisher’s usual cautious methods. This strolling in and helping oneself was certainly kidnapping de luxe. In the small hours I could have understood it; but at nine o’clock at night, with Glossop, Mr. Abney, and myself awake and liable to be met at any moment on the stairs, it was absurd. I marvelled at Smooth Sam’s effrontery.

I lay still. I imagined that, being in, he would switch on the electric light. He did, and I greeted him pleasantly.

“And what can I do for you, Mr. Fisher?”

For a man who had learned to control himself in difficult situations he took the shock badly. He uttered a startled exclamation, and spun round, open-mouthed.

“I—I,” he stammered, “I didn’t know you were here.”

“Quite a pleasant surprise. Do you want anything?”

I could not help admiring the quickness with which he recovered himself. Almost immediately he was the suave, chatty Sam Fisher who had unbosomed his theories and dreams to me in the train to London.

“I quit,” he said, pleasantly. “The episode is closed. I would not dream of competing with you, sonny, in a physical struggle. And I take it that you would not keep on lying quietly on that bed while I went into the other room and abstracted our young friend? Or maybe you have changed your mind again? Would a fifty-fifty offer tempt you?”

“Not an inch.”

“No, no. So I suspected. I merely asked.”

“And how about Mr. Abney, in any case? Suppose we met him on the stairs?”

“We should not meet him on the stairs,” said Sam, confidently. “You did not take coffee to-night, I gather?”

“I didn’t—no. Why?”

He jerked his head resignedly.

“Can you beat it! I ask you, young man, could I have foreseen that, after drinking coffee every night regularly for two months, you would pass it by to-night of all nights?”

His words had brought light to me.

“Did you drug the coffee?”

“Did I! I fixed it so that one sip would have an insomnia patient in dreamland before he had time to say ‘Good night.’ That stuff Rip Van Winkle drank had nothing on my coffee. And all wasted! Well, well!”

He turned towards the door.

“Shall I leave the light on, or would you prefer it off?”

“On, please. I might fall asleep in the dark.”

“Not you! And if you did, you would dream that I was there, and wake up. There are moments, young man, when you bring me pretty near to quitting and taking to honest work.”

“Why don’t you?”

“But not altogether. I have still a shot or two in my locker. We shall see what we shall see. I am not dead yet. Wait!”

“I will. And some day, when I am walking along Piccadilly, a passing automobile will splash me with mud. A heavily furred plutocrat will stare haughtily at me from the tonneau, and with a start of surprise I shall recognise——”

“Stranger things have happened. Be fresh while you can, sonny. You win so far, but this hoodoo of mine can’t last for ever.”

He passed from the room with a certain sad dignity. A moment later he reappeared.

“A thought strikes me,” he said. “The fifty-fifty proposition does not impress you. Would it make things easier if I were to offer my co-operation for a mere quarter of the profits?”

“Not in the least.”

“It’s a handsome offer.”

“It is. But I am not dealing on any terms.”

He left the room only to return once more.

His head appeared, staring at me round the door in a disembodied way, like the Cheshire cat.

“You won’t say later on I didn’t give you your chance?”

He vanished again, permanently this time. I heard his steps passing down the stairs.

We had now arrived at the last week of term—at the last days of the last week. The vacation spirit was abroad in the school. Among the boys it took the form of increased disorderliness. Boys who had merely spilt ink now broke windows. Ogden Ford abandoned cigarettes in favour of an old clay pipe which he had found in the stables.

Complete quiescence marked the deportment of Mr. Fisher during these days. He did not attempt to repeat his last effort. The coffee came to the study unmixed with alien drugs. Sam, like lightning, did not strike twice in the same place. He had the artist soul, and disliked patching up bungled work.

If he made another move, it would, I knew, be on entirely fresh lines.

Ignoring the fact that I had had all the luck, I was inclined to be self-satisfied when I thought of Sam. I had pitted my wits against his, and I had won. It was a praiseworthy performance for a man who had done hitherto nothing particular in his life.

If all the copy-book maxims which had been drilled into me in my childhood had not been sufficient, I ought to have been warned by Sam’s advice not to take victory for granted till the fight was over. As Sam had said, his misfortunes could not last for ever. The luck would turn sooner or later.

One realises these truths in theory, but the practical application of them seldom fails to come as a shock. I received mine on the last morning but one of the term.

Shortly after breakfast a message was brought to me that Mr. Abney would like to see me in his study. I went without any sense of disaster to come. Most of the business of the school was discussed in the study after breakfast, and I imagined that the matter had to do with some detail of the morrow’s exodus.

I found Mr. Abney pacing the room, a look of annoyance on his face.

There was a touch of embarrassment in Mr. Abney’s manner, for which I could not at first account. He coughed once or twice before proceeding to the business of the moment.

“Ah, Mr. Burns,” he said at length, “might I ask if your plans for the holidays—the—ah—earlier part of the holidays—are settled?”

“No,” I said; “I shall go to London for a day or two, I think.”

He produced a letter from the heap of papers on the desk.

“Ah—excellent. That simplifies matters considerably. I have no right to ask what I am about to—ah—in fact, ask. I have no claim on your time in the holidays. But in the circumstances perhaps you may see your way to doing me a considerable service. I have received a letter from Mr. Elmer Ford, who landed in England yesterday morning, which puts me in a position of some difficulty. It is not my wish to disoblige the parents of the boys who are entrusted to my care, and I should like, if possible, to do what Mr. Ford asks. It appears that certain business matters call him to the North of England for a few days, thus rendering it impossible for him to receive little Ogden. I must say that a little longer notice would have been a—in fact, a convenience. But Mr. Ford, like so many of his countrymen, is what I believe is called a hustler. ‘He does it now,’ as the expression is. In short, he wishes to leave little Ogden at the school for the first few days of the holidays, and I should be extremely obliged, Mr. Burns, if you could find it possible to stay here and—ah—look after him.”

Mr. Abney coughed again, and resumed.

“I would stay myself, but the fact is I am called to London on very urgent business.”

He pressed the bell.

“In the event of your observing any suspicious characters in the neighbourhood, you have the telephone, and can instantly communicate with the police. And you will have the assistance of——”

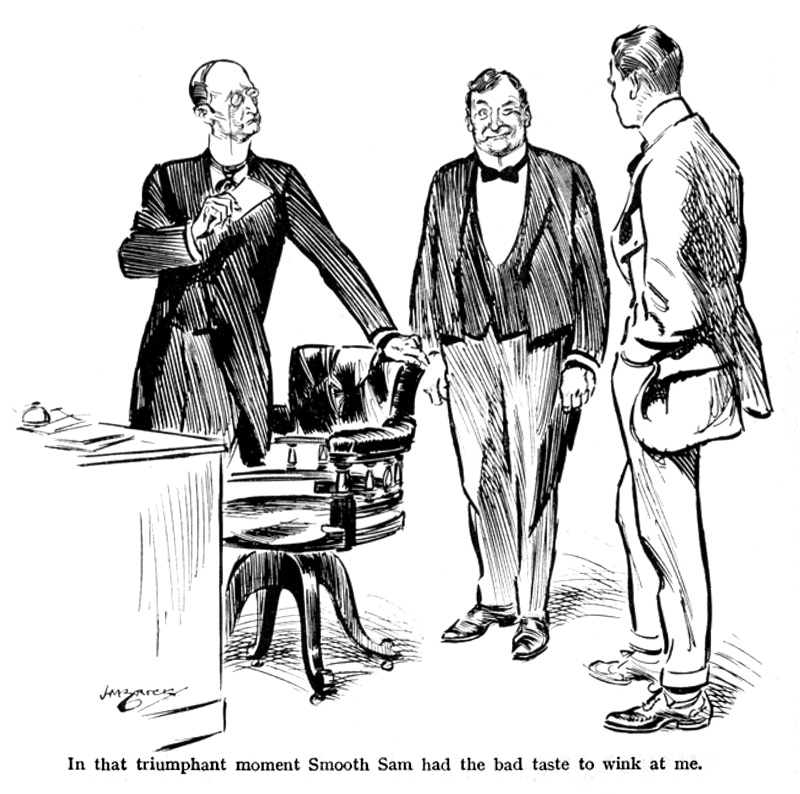

The door opened, and Smooth Sam Fisher entered.

“You rang, sir?”

“Ah! Come in, White, and close the door. I have something to say to you. I have just been informing Mr. Burns that Mr. Ford has written asking me to allow his son to stay on at the school for the first few days of the vacation. The whole arrangement is excessively unusual, and I may say—ah—disturbing. However, you have your duty to fulfil to your employer, White, and you will, of course, remain here with the boy.”

“Yes, sir.”

I found myself looking into a bright brown eye that gleamed with genial triumph. The other was closed. In the exuberance of the moment, Smooth Sam had had the bad taste to wink at me.

“You will have Mr. Burns to help you, White. He has kindly consented to postpone his departure during the short period in which I shall be compelled to be absent.”

I had no recollection of having given any kind consent, but I was very willing to have it assumed. That wink had roused my fighting spirit.

I was glad to see that Mr. Fisher, though Mr. Abney did not observe it, was visibly taken aback by this piece of information. But he made one of his swift recoveries.

“It is very kind of Mr. Burns,” he said, in his fruitiest voice, “but I hardly think it will be necessary to put him to the inconvenience of altering his plans. I am sure that Mr. Ford would prefer the entire charge of the affair to be in my hands.”

He had not chosen a happy moment for the introduction of the millionaire’s name. Mr. Abney was a man of method, who hated any dislocation of the fixed routine of life; and Mr. Ford’s letter had upset him. The Ford family, father and son, were just then extremely unpopular with him.

He crushed Sam.

“What Mr. Ford would or would not prefer is, in this particular matter, beside the point. The responsibility for the boy, while he remains on the school premises, is—ah—mine, and I shall take such precautions as seem fit and adequate to—h’m—myself, irrespective of those which, in your opinion, might suggest themselves to Mr. Ford. As I cannot be here myself, owing to—ah—urgent business in London, I shall certainly take advantage of Mr. Burns’s kind offer to remain as my deputy.”

“Very well, sir,” said Sam meekly.

I spent the rest of the day in London, returning to Sanstead by the last train. Mr. Abney gave me leave reluctantly, for the request was certainly unusual. He asked me if it was absolutely essential that I should go to London. I said that it was. I thought so too. My object in making the journey was to buy a Browning pistol. I was taking no risks with Smooth Sam Fisher.

CHAPTER X

exit and re-enter sam

A SCHOOL during the holidays is a lonesome spot. There was a weirdly deserted air about the whole place when the last cab had rolled off on its way to the station. I roamed restlessly through the grounds with Ogden. A stillness brooded over everything, as if the place had been laid under a spell. Never before had I been so impressed with the isolation of Sanstead House. Anything might happen in this lonely spot, and the world would go on its way in ignorance.

It was not long before the inconveniences of my watch-dog life began to be borne in upon me. Shortly after lunch I became aware that I needed tobacco, and that speedily, or the night would find me destitute. The nearest tobacconist’s shop was two miles away, next door to the “Feathers.” I had to have it, and yet I could not leave Ogden. I was obliged to take him with me, and a less congenial companion for a country walk I have never met. He loathed exercise, and said so in a number of ways until we reached the shop.

As we were coming out, a man emerged from the “Feathers.” He growled unintelligibly, for I had nearly collided with him; then suddenly uttered an exclamation, and stared at Ogden.

There was no need for introductions. It was my much enduring acquaintance, Mr. Buck Macginnis.

The next moment he had moved off down the street. He walked quickly. His leg appeared to be restored to its old perfection.

I stood looking after him. The vultures were gathered together with a vengeance. Sam within, Buck without—it was quite like old times.

“We’ll have a cab back to the house,” I said to Ogden, who received the information with sombre pleasure.

It had occurred to me that Mr. Macginnis might have formed some idea of ambushing our little expedition on the way home.

My mind was active in the cab. It was not hard to account for Buck’s reappearance. He would, of course, have made it his business to get early information of Mr. Ford’s movements. It would be easy for him to discover that the millionaire had been called away to the North, and that Ogden was still an inmate of Sanstead House. And here he was, preparing for the grand attack.

I had been premature in removing Buck’s name from the list of active combatants. Broken legs mend. I ought to have remembered that.

His presence on the scene made, I perceived, a vast difference to my plan of campaign. It was at this point that my purchase of the Browning pistol really appeared in the light of an acute strategic move. With Buck, that disciple of the frontal attack, in the field, there might be need for it.

Long before the cab drew up at the door of Sanstead House, I had made up my mind on the point of my next move. I proposed to eject Sam without delay. I had shrunk from this high-handed move till now, but the reappearance of Buck left me no choice.

I settled Ogden in the study, and went in search of him. He would, I imagined, be in the housekeeper’s room—a cosy little apartment off the passage leading to the kitchen. I decided to draw that first, and was rewarded, on pushing open the half-closed door, by the sight of a pair of black-trousered legs stretched out before me from the depths of a wicker-work armchair. His portly middle section, rising beyond like a small hill, heaved rhythmically. His face was covered with a silk handkerchief, from beneath which came, in even succession, faint and comfortable snores. It was a peaceful picture—the good man taking his rest.

Pleasing as Sam was as a study in still life, pressure of business compelled me to stir him into activity. I prodded him gently in the centre of the rising territory beyond the black trousers. He grunted discontentedly, and sat up. The handkerchief fell from his face. He blinked at me—at first with the dazed glassiness of the newly awakened, then with a “Soul’s Awakening” expression, which spread over his face until it melted into a friendly smile.

“Hello, young man!”

“Good afternoon. You seem tired.”

He yawned cavernously.

“Forty winks. It clears the brain.”

“Had all you want?”

His face split in another mammoth yawn. He threw his heart into it, as if life held no other tasks for him. Only in alligators have I ever seen its equal.

“I guess I’m through,” he said.

“Then out you get, Mr. Fisher.”

“Eh?”

“Take your last glimpse of the old home, Sam, and out into the hard world.”

He looked at me inquiringly. “You seem to be talking, young man. Words appear to be fluttering from you. But your meaning, if any, escapes me.”

“My meaning is that I am about to turn you out. There is not room for both of us here. So, if you do not see your way to going quietly, I shall take you by the back of the neck and run you out. Do I make myself fairly clear now?”

He permitted himself a rich chuckle.

“You have gall, young man. Well, I hate to seem unfriendly. I like you, sonny. You amuse me—but there are moments when one wants to be alone. Trot along, kiddo, and quit disturbing uncle. Tie a string to yourself and disappear. Bye-bye.”

The wicker-work creaked as he settled his stout body. He picked up a newspaper.

“Mr. Fisher,” I said, “I have no wish to propel your grey hairs at a rapid run down the drive, so I will explain further. I mean to turn you out. How can you prevent it? Mr. Abney is away. You can’t appeal to him. The police are at the end of the telephone, but you can’t appeal to them. As you said yourself, you can’t compete with me in a physical struggle. So what can you do except go? Do you get me now?”

He regarded the situation in thoughtful silence. He allowed no emotion to find expression in his face, but I knew that the significance of my remarks had sunk in. I could almost follow his mind, as he tested my position point by point, and found it impregnable.

When he spoke it was to accept defeat jauntily.

“Very well, young man. Just as you say. You’re really set on my going? Say no more. I’ll go. After all it’s quiet at the inn, and what more does a man want?”

The day dragged on. I spent the greater part of it walking about the grounds. Towards night the weather broke suddenly after the fashion of spring in England. Showers of rain drove me to the study.

It must have been nearly ten o’clock when the telephone rang.

It was Sam.

“Hello, is that you, Mr. Burns?”

“It is. Do you want anything?”

“I want a talk with you. Business. Can I come up? I’m at ‘The Feathers.’ ”

“If you wish it.”

“I’ll start right away.”

It was some fifteen minutes later that I heard in the distance the engines of an automobile. The head-lights gleamed through the trees, and presently the car swept round the bend of the drive and drew up at the front door. A portly figure got down and rang the bell. I observed these things from a window on the first floor overlooking the front steps, and it was from this window that I spoke.

“Is that you, Mr. Fisher?”

He backed away from the door.

“Where are you?”

“Is that your car?”

“It belongs to a friend of mine.”

“I didn’t know you meant to bring a party.”

“There’s only three of us. Me, the chauffeur, and my friend—Macginnis.”

The possibility, indeed the probability, of Sam seeking out Buck and forming an alliance had occurred to me, and I was prepared for it. I shifted my grip on the automatic pistol in my hand.

“Mr. Fisher.”

“Hello?”

“Ask your friend Macginnis to be good enough to step into the light of that lamp, and drop his pistol.”

(To be concluded)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums