The Captain, March 1913

CHAPTER XI

cut off

THERE was a muttered conversation. I heard Buck’s voice rumbling like a train going under a bridge. The request did not appear to find favour with him. Then came an interlude of soothing speech from Mr. Fisher. I could not distinguish the words, but I gathered that he was pointing out to him that, on this occasion only, the visit being for purposes of parley and not of attack, pistols might be looked on as non-essentials. Whatever his arguments they were successful, for, finally, humped as to the back and muttering, Buck appeared in the spotlight.

“Good evening, Mr. Macginnis,” I said. “I’m glad to see your leg is all right again. I won’t detain you a moment. Just feel in your pockets and shed a few of your guns, and then you can come in out of the rain. To prevent any misunderstanding, I may say I have a gun of my own. It is trained on you now.”

“I ain’t got no gun.”

“Come along. This is no time for airy persiflage. Out with them.”

A moment’s hesitation, and a small black pistol fell to the ground.

“No more?”

“Think I’m a regiment?”

“I don’t know what you are. Well, I’ll take your word for it. You will come in one by one with your hands up.”

I went down and opened the door, holding my pistol in readiness against the unexpected.

Sam came first. His raised hands gave him a vaguely pontifical air (Bishop blessing Pilgrims), and the kindly smile he wore heightened the illusion. Mr. Macginnis, who followed, suggested no such idea. He was muttering moodily to himself, and he eyed me askance.

I showed them into the class-room, and switched on the light. The air was full of many odours. Disuse seems to bring out the inky, chalky, appley, deal-boardy bouquet of a class-room as the night brings out the scent of flowers. During the term I had never known this class-room smell so exactly like a class-room. I made use of my free hand to secure and light a cigarette.

Sam rose to a point of order.

“Young man,” he said, “I should like to remind you that we are here, as it were, under a flag of truce. To pull a gun on us and keep us holding our hands up this way is raw work. I feel sure I speak for my friend, Mr. Macginnis.”

He cocked an eye at his friend Mr. Macginnis, who seconded the motion by expectorating into the fire-place.

“Mr. Macginnis agrees with me,” said Sam, cheerfully. “Do we take them down? Have we your permission to assume position two of these Swedish exercises? All we came for was a little friendly chat among gentlemen, and we can talk just as well—speaking for myself, better—in a less strained attitude. A little rest, Mr. Burns? A little folding of the hands? Thank you.”

He did not wait for permission; nor was it necessary. Sam and the melodrama atmosphere were as oil and water. It was impossible to blend them. I laid the pistol on the table and sat down. Buck, after one wistful glance at the weapon, did the same. Sam was already seated, and was looking so cosy and at home that I almost felt it remiss of me not to have provided sherry and cake for this pleasant gathering.

“Well,” I said; “what can I do for you?”

“Let me explain,” said Sam. “As you have no doubt gathered, Mr. Macginnis and I have gone into partnership.”

“I gathered that. Well?”

“Judicious partnerships are the soul of business. Mr. Macginnis and I have been rivals in the past, but we both saw that the moment had come for an alliance. We form a strong team. My partner’s speciality is action. I supply the strategy. Say, sonny, can’t you see you’re up against it? Why be foolish?”

“You think you’re certain to win?”

“It’s a cinch.”

“Then why trouble to come here and see me?”

I appeared to have put into words the smouldering thought which was vexing Mr. Macginnis. He burst into speech.

“Sure! What’s de use? Didn’t I tell youse? What’s de use of wastin’ time? What are we spielin’ away here for? Let’s get busy.”

Sam waved a hand towards him with the air of a lecturer making a point.

“You see! The man of action! He likes trouble. He asks for it. Now I prefer peace. Why have a fuss when you can get what you want quietly? That’s my motto. That’s why we’ve come. It’s the old proposition. We’re here to buy you out. Yes, I know you have turned the offer down before, but things have changed. Your stock has fallen. In fact, instead of letting you in on sharing terms, we only feel justified now in offering a commission. For the moment you may seem to hold a strong position. You are in the house, and you have got the boy. But there’s nothing to it really. We could get him in five minutes if we cared to risk having a fuss. But it seems to me there’s no need of any fuss. We should win dead easy all right if it came to trouble; but, on the other hand, you’ve a gun, and there’s a chance some of us might get hurt; so what’s the good when we can settle it quietly? How about it, sonny?”

Mr. Macginnis began to rumble, preparatory to making further remarks on the situation, but Sam waved him down and turned his brown eye inquiringly on me.

“Fifteen per cent is our offer,” he said.

“And to think it was once fifty-fifty!”

“Strict business!”

“Business! It’s sweating!”

“It’s our limit. And it wasn’t easy to make Buck here agree to that. He kicked like a mule.”

Buck shuffled his feet, and eyed me disagreeably. I suppose it is hard to think kindly of a man who has broken your leg. It was plain that, with Mr. Macginnis, bygones were by no means bygones.

I rose.

“Well, I’m sorry you should have had the trouble of coming here for nothing. Let me see you out. Single file, please.”

Sam looked aggrieved.

“You turn it down?”

“I do.”

“One moment. Let’s have this thing clear. Do you realise what you’re up against? Don’t think it’s only Buck and me you’ve got to tackle. All the boys are here, waiting around the corner, the same gang that came the other time. Be sensible, sonny. You don’t stand a dog’s chance. I shouldn’t like to see you get hurt. And you never know what may not happen. The boys are pretty sore at you because of what you did that night. I shouldn’t act like a bonehead, sonny—honest.”

There was a kindly ring in his voice which rather touched me. Between him and me there had sprung up an odd sort of friendship. He meant business, but he would, I knew, be genuinely sorry if I came to harm. And I could see that he was quite sincere in his belief that I was in a tight corner and that my chances against the combine were infinitesimal. I imagine that, with victory so apparently certain, he had had difficulty in persuading his allies to allow him to make his offer.

But he had overlooked one thing—the telephone. That he should have made this mistake surprised me. If it had been Buck, I could have understood it. Buck’s was a mind which lent itself to such blunders. From Sam I had expected better things, especially as the telephone had been so much in evidence of late. He had used it himself only half an hour ago.

I clung to the thought of the telephone. It gave me the quiet satisfaction of the gambler who holds the unforeseen ace. The situation was in my hands. The police, I knew, had been profoundly stirred by Mr. Macginnis’s previous raid. When I called them up, as I proposed to do directly the door had closed on the ambassadors, there would be no lack of response. It would not again be a case of Inspector Bones and Constable Johnson to the rescue. A great cloud of willing helpers would swoop to our help.

With these thoughts in my mind, I answered Sam pleasantly but firmly.

“I’m sorry I’m unpopular, but all the same——”

I indicated the door.

Emotion that could only be expressed in words and not through his usual medium welled up in Mr. Macginnis. He sprang forward with a snarl, falling back as my faithful automatic caught his eye.

“Say, you! Listen here! You’ll——”

Sam, the peaceable, plucked at his elbow.

“Nothing doing. Step lively.”

Buck wavered, then allowed himself to be drawn away. We passed out of the class-room in our order of entry.

I opened the front door, and they passed out. The automobile was still purring on the drive. Buck’s pistol had disappeared. I suppose the chauffeur had picked it up, a surmise which proved to be correct a few moments later, when, just as the car was moving off, there was a sharp crack, and a bullet struck the wall to the right of the door. It was a random shot, and I did not return it. Its effect on me was to send me into the hall with a leap that was almost a back-somersault. Somehow, though I was keyed up for violence and the shooting of pistols, I had not expected it at just that moment, and I was disagreeably surprised at the shock it had given me. I slammed the door and bolted it. I was intensely irritated to find that my fingers were trembling.

I went straight to the study, and unhooked the telephone.

There is apt to be a certain leisureliness about the methods of country telephone-operators, and the fact that a voice did not immediately ask me what number I wanted did not at first disturb me. Suspicion of the truth came to me, I think, after my third shout into the receiver had remained unanswered. I had suffered from delay before, but never such delay as this.

I must have remained there fully two minutes, shouting at intervals, before I realised the truth. Then I dropped the receiver and leaned limply against the wall. For the moment I was as stunned as if I had received a blow. I could not even think. I took up the receiver again, and gave another call. There was no reply.

They had cut the wires.

CHAPTER XII

the first round

I REVIEWED my position. Daylight would bring relief, for I did not suppose that even Buck Macginnis would care to conduct a siege which might be interrupted by the arrival of tradesmen in their carts and other visitors; but while the darkness lasted I was completely cut off from the world. With the destruction of the telephone-wire my only link with civilisation had been snapped. Even had the night been less stormy than it was, there was no chance of the noise of our warfare reaching the ears of anyone who might come to the rescue. It was as Sam had said; Buck’s energy united to his strategy formed a strong combination.

Broadly speaking, there are only two courses open to a beleaguered garrison. It can stay where it is, or it can make a sortie. I considered the second of these courses.

It was possible that Sam and his allies had departed in the automobile to get reinforcements, leaving the coast temporarily clear; in which case, by escaping from the house at once, I might be able to get Ogden away unobserved through the grounds and reach the village in safety. To support this theory there was the fact that the car, on its late visit, had contained only the chauffeur and the two ambassadors, while Sam had spoken of the remainder of Buck’s gang as being in readiness to attack in the event of my not coming to terms. That might mean that they were waiting at Buck’s headquarters, wherever those might be—at one of the cottages down the road, I imagined—and, in the interval before the attack began, it might be possible for us to make our sortie with success.

I strained my eyes at the window, but it was impossible to see anything. The rain was still falling heavily. If the drive had been full of men, they would have been invisible to me.

I decided to make the sortie. Ogden was in bed. He woke when I shook him, and sat up, yawning the aggrieved yawns of one roused from his beauty sleep.

“What’s all this?” he demanded.

“Listen,” I said. “Buck Macginnis and Smooth Sam Fisher have come after you. They are outside now. Don’t be frightened.”

He snorted derisively.

“Who’s frightened? I guess they won’t hurt me. How do you know it’s them?”

“They have just been here. The man who called himself White, the butler, was really Sam Fisher. He has been waiting his opportunity to get you all the term.”

“White! Was he Sam Fisher?” He chuckled admiringly. “Say, he’s a wonder!”

“They have gone to fetch the rest of the gang.”

“Why don’t you call the cops?”

“They have cut the wire.”

His only emotions at the news seemed to be amusement and a renewed admiration for Smooth Sam. He smiled broadly, the little brute.

“He’s a wonder!” he repeated. “I guess he’s smooth all right. He’s the limit! He’ll get me all right this trip. I bet you a nickel he wins out.”

I found his attitude trying. That he, the cause of all the trouble, should be so obviously regarding it as a sporting contest got up for his entertainment, was hard to bear. And the fact that, whatever might happen to myself, he was in no danger, comforted me not at all. If I could have felt that we were in any way companions in peril, I might have looked on the bulbous boy with quite a friendly eye. As it was, I nearly kicked him.

“Are you ready?” I said. “We have no time to waste.”

“What’s that?”

“We are going to steal out through the back way, and try to slip through to the village.”

Ogden’s comment on the scheme was brief and to the point. He did not embarrass me with fulsome praise of my strategic genius.

“Of all the fool games!” he said, simply. “In this rain? No, sir!”

This new complication was too much for me. In planning out my manœuvres I had taken his co-operation for granted. I had looked on him as so much baggage—the impediment of the retreating army. And, behold, a mutineer!

I took him by the scruff of the neck and shook him. It was a relief to my feelings and a sound move. The argument was one which he understood.

“Oh, all right,” he said. “Anything you like. Come on. But it sounds to me like darned foolishness.”

If nothing else had happened to spoil the success of that sortie, Ogden’s depressing attitude would have done so. Of all things, it seems to me, a forlorn hope should be undertaken with a certain enthusiasm and optimism if it is to have a chance of being successful. Ogden threw a gloom over the proceedings from the start. He was cross and sleepy, and he condemned the expedition unequivocally. As we moved towards the back door he kept up a running stream of abusive comment. I silenced him before cautiously unbolting the door, but he had said enough to damp my spirits. I do not know what effect it would have had on Napoleon’s tactics if his army—say, before Austerlitz—had spoken of his manœuvres as “a fool game,” and of himself as a “big chump,” but I doubt if it would have stimulated him.

The back door of Sanstead House opened on to a narrow yard, paved with flag-stones and shut in on all sides but one by walls. To the left was the outhouse where the coal was stored—a squat, barn-like building; to the right a wall that appeared to have been erected by the architect in an outburst of pure whimsicality. It just stood there. It served no purpose that I had ever been able to discover, except to act as a cats’ club-house.

To-night, however, I was thankful for this wall. It formed an important piece of cover. By keeping in its shelter it was possible to work round the angle of the coal-shed, enter the stable-yard, and, by making a detour across the football field, avoid the drive altogether. And it was the drive, in my opinion, that might be looked on as the danger zone.

Ogden’s complaints, which I had momentarily succeeded in checking, burst out afresh as the rain swept in at the opened door and lashed our faces. Certainly it was not an ideal night for a ramble. The wind was blowing through the opening at the end of the yard with a compressed violence due to the confined space. There was a suggestion in our position of the Cave of the Winds under Niagara Falls, the verisimilitude of which was increased by the stream of water that poured down from the gutter above our heads. Ogden found it unpleasant, and said so shrilly.

I pushed him out into the storm, still protesting, and we began to creep across the yard. Half-way to the first point of importance of our journey, the corner of the coal-shed, I halted the expedition. There was a sudden lull in the wind, and I took advantage of it to listen.

From somewhere beyond the wall, apparently near the house, sounded the muffled note of the automobile. The siege party had returned.

There was no time to be lost. Apparently the possibility of a sortie had not yet occurred to Sam, or he would hardly have left the back door unguarded; but a general of his astuteness was certain to remedy the mistake soon, and our freedom of action might be a thing of moments. It behoved us to reach the stable-yard as quickly as possible. Once there we should be practically through the enemy’s lines.

Administering a kick to Ogden, who showed a disposition to linger and talk about the weather, I moved on, and we reached the corner of the coal-shed in safety.

We had now arrived at the really perilous stage in our journey. Having built his wall to a point level with the end of the coal-shed, the architect had apparently wearied of the thing and given it up, for it ceased abruptly, leaving us with a matter of half a dozen yards of open ground to cross, with nothing to screen us from the watchers on the drive. The flag-stones, moreover, stopped at this point. On the open space was loose gravel. Even if the darkness allowed us to make the crossing unseen, there was the risk that we might be heard.

It was a moment for a flash of inspiration, and I was waiting for one, when that happened which took the problem out of my hands. From the interior of the shed on our left there came a sudden scrabbling of feet over loose coal, and through the square opening in the wall, designed for the peaceful purpose of taking in sacks, climbed two men. A pistol cracked. From the drive came an answering shout. We had been ambushed.

I had misjudged Sam. He had not overlooked the possibility of a sortie.

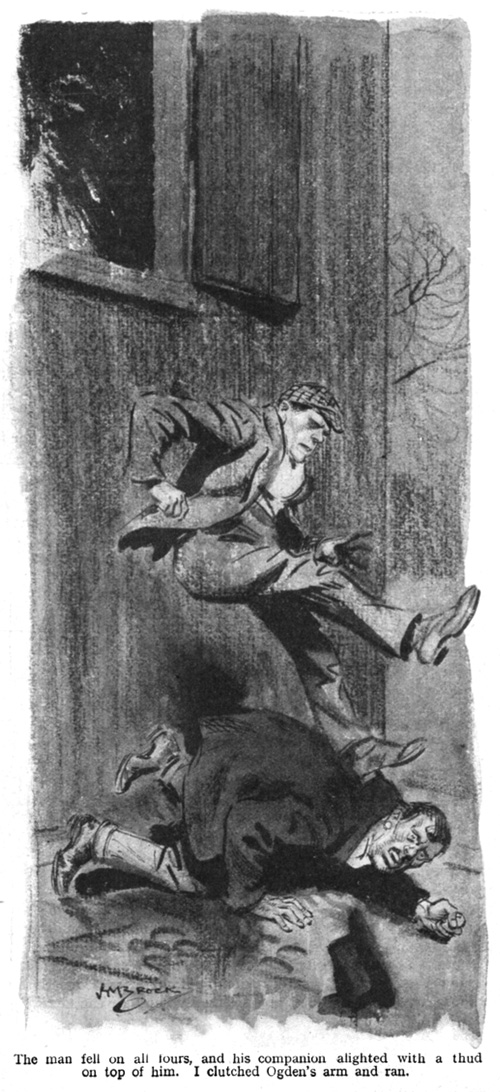

It is the accidents of

life that turn the scale in a crisis. The opening through which the men had

leaped was scarcely a couple of yards behind the spot where we were standing.

If they had leaped fairly and kept their feet they would have been on us before

we could have moved. But Fortune ordered it that, zeal outrunning discretion,

the first of the two should catch his foot in the wood-work and fall on all

fours, while the second, unable to check his spring, alighted on top of him,

and, judging from the stifled yell which followed, must have kicked him in the

face.

It is the accidents of

life that turn the scale in a crisis. The opening through which the men had

leaped was scarcely a couple of yards behind the spot where we were standing.

If they had leaped fairly and kept their feet they would have been on us before

we could have moved. But Fortune ordered it that, zeal outrunning discretion,

the first of the two should catch his foot in the wood-work and fall on all

fours, while the second, unable to check his spring, alighted on top of him,

and, judging from the stifled yell which followed, must have kicked him in the

face.

In the moment of their downfall I was able to form a plan and execute it.

I clutched Ogden, and broke into a run; and we were across the open space and in the stable-yard before the first of the men in the drive loomed up through the darkness. Half of the wooden double-gate of the yard was open, and the other half served us as a shield. They fired as they ran—at random, I think, for it was too dark for them to have seen us clearly—and two bullets slapped against the gate. A third struck the wall above our heads, and ricochetted off into the night. But before they could fire again we were in the stables, the door slammed behind us, and I had dumped Ogden on the floor, and was shooting the heavy bolts into their places. Footsteps clattered over the flagstones, and stopped outside. Some weighty body plunged against the door. Then there was silence. The first round was over.

CHAPTER XIII

round two

THE stables, as is the case in most English country houses, had been, in its palmy days, the glory of Sanstead House. In whatever other respect the British architect of that period may have fallen short, he never scamped his work on the stables. He built them strong and solid, with walls fitted to repel the assaults of the weather, and possibly those of men as well; for the Boones in their day had been mighty owners of race-horses at a time when men with money at stake did not stick at trifles, and it was prudent to see to it that the spot where the favourite was housed had something of the nature of a fortress. The walls were thick, the door solid, the windows barred with iron. We could scarcely have found a better haven of refuge.

Under Mr. Abney’s rule the stables had lost their original character. They had been divided into three compartments, each separated by a stout wall. One compartment became a gymnasium, another the carpenter’s shop, the third, in which we were, remained a stable, though in these degenerate days no horse ever set hoof inside it, its only use being to provide a place for the odd-job man to clean shoes. The mangers which had once held fodder were given over now to brushes and pots of polish. In term-time bicycles were stored in the loose-box which had once echoed to the trampling of Derby favourites.

I groped about among the pots and brushes, and found a candle-end, which I lit. I was running a risk, but it was necessary to inspect our ground. I had never troubled really to examine this stable before, and I wished to put myself in touch with its geography.

I blew out the candle, well content with what I had seen. The only two windows were small, high up, and excellently barred. Even if the enemy fired through them, there were half a dozen spots where we should be perfectly safe. Best of all, in the event of the door being carried by assault, we had a second line of defence in a loft. A ladder against the back wall led to it, by way of a trap-door. Circumstances had certainly been kind to us in driving us to this apparently impregnable shelter.

On concluding my inspection, I became aware that Ogden was still occupied with his grievances. I think the shots must have stimulated his nerve-centres, for he had abandoned the languid drawl with which, in happier moments, he was wont to comment on life’s happenings, and was dealing with the situation with a staccato brightness.

“Of all the darned fool lay-outs I ever struck this is the limit. What do those idiots think they’re doing, shooting us up that way? It went within an inch of my head. It might have killed me. Gee, and I’m all wet! I’m catching cold. It’s all through your foolishness bringing us out here. Why couldn’t we stay in the house?”

“We could not have kept them out of the house for five minutes,” I explained. “We can hold this place.”

“Who wants to hold it? I don’t. What does it matter if they do get me? I don’t care. I’ve a good mind to walk straight out through that door and let them rope me in. It would serve dad right. It would teach him not to send me away from home to any darned school again. What did he want to do it for? I was all right where I was. I——”

A loud hammering on the door cut off his eloquence. The intermission was over and the second round had begun.

It was pitch dark in the stable now that I had blown out the candle, and there is something about a combination of noise and darkness which tries the nerves. If mine had remained steady, I should have ignored the hammering. From the sound, it appeared to be made by some wooden instrument—a mallet from the carpenter’s shop, I discovered later—and the door could be relied on to hold its own without any intervention. For a novice to violence, however, to maintain a state of calm inaction is the most difficult feat of all. I was irritated and worried by the noise, and I exaggerated its importance. It seemed to me that it must be stopped at once.

A moment before I had bruised my shins against an empty packing-case, which had found its way with other lumber into the stable. I groped for this, swung it noiselessly into position beneath the window, and, standing on it, looked out. I found the catch of the window, and opened it. There was nothing be seen, but the sound of the hammering became more distinct; and, pushing an arm through the bars, I emptied my pistol at a venture.

As a practical move, the action had flaws. The shots cannot have gone anywhere near their vague target. But as a demonstration it was a wonderful success.

The yard became suddenly full of dancing bullets. They struck the flag-stones, bounded off, chipped the bricks of the far wall, ricochetted to from those, buzzed in all directions, and generally behaved in a manner calculated to unman the stoutest-hearted.

The siege-party did not stop to argue. They stampeded as one man. I could hear them clattering across the flag-stones to every point of the compass. In a few seconds silence prevailed, broken only by the swish of the rain. Round two had been brief, hardly worthy to be called a round at all, and, like round one, it had ended wholly in our favour.

I jumped down from my packing-case, swelling with pride. I had had no previous experience of this sort of thing, yet here I was handling the affair like a veteran. I considered that I had a right to feel triumphant. I lit the candle again, and beamed protectively upon Ogden.

He was sitting on the floor gaping feebly, and awed for the moment into silence.

“I didn’t hit anybody,” I announced, “but they ran like rabbits. They are all over Hampshire.”

I was pleased with myself. I laughed indulgently. I could afford an attitude of tolerant amusement towards the enemy.

“They’ll come back,” said Ogden, morosely.

“Possibly. And in that case——” I felt in my left-hand coat-pocket. “I had better be getting ready.” I felt in my right-hand coat-pocket.

A clammy coldness took possession of me.

“Ready,” I repeated blankly. My voice trailed off into nothingness. For in neither pocket was there a single one of the shells with which I had fancied that I was abundantly provided.

In moments of excitement Man is apt to make mistakes. I had made mine when starting out on the sortie. I had left all my ammunition in the house.

CHAPTER XIV

round three, and last

I SHOULD like to think that it was an unselfish desire to spare my young companion anxiety that made me keep my discovery to myself. But I am afraid that my reticence was due far more to the fact that I shrank from letting him discover my imbecile carelessness. Even in times of peril one retains one’s human weaknesses, and I felt that I could not face his comments. If he had permitted a certain note of querulousness to creep into his conversation already, the imagination recoiled from the thought of the caustic depths he would reach now, should I reveal the truth.

I tried to make things better with cheery optimism.

“They won’t come back,” I said stoutly; and tried to believe it.

Ogden, as usual, struck the jarring note.

“Well, then, let’s beat it,” he said. “I don’t want to spend the night in this wretched ice-house. I tell you I’m catching cold. My chest’s weak. If you’re so dead certain you’ve scared them away let’s quit.”

I was not prepared to go so far as this.

“They may be somewhere near, hiding.”

“Well, what if they are? I don’t mind being kidnapped. Let’s go.”

“It would be madness to go out now.”

“Oh, pshaw,” said Ogden, and from this point onwards punctuated the proceedings with a hacking cough.

I had never really believed that my demonstration had brought the siege to a definite end. I anticipated that there would be some delay before the renewal of hostilities, but I was too well acquainted with Buck Macginnis’s tenacity to imagine that he would abandon his task because a few random shots had spread momentary panic in his ranks. He had all the night before him, and sooner or later he would return.

I had judged him correctly. Many minutes dragged wearily by without a sign from the enemy. Then, listening at the window, I heard footsteps crossing the yard and voices talking in cautious undertones. The fight was on once more.

A bright light streamed through the window, flooding the opening and spreading in a wide circle on the ceiling. It was not difficult to understand what had happened. They had gone to the automobile and come back with one of the head-lamps, an astute move, in which I seemed to see the finger of Sam.

The danger-spot thus rendered harmless, they renewed their attack on the door with a reckless vigour. The mallet had been superseded by some heavier instrument—of iron this time. I think it must have been the jack from the automobile. It was a more formidable weapon altogether than the mallet, and even our good oak door quivered under it.

A splintering of wood decided me that the time had come to retreat to our second line of entrenchments. How long the door would hold it was impossible to say, but I doubted if it were more than a matter of minutes.

Relighting my candle, which I had extinguished from motives of economy, I caught Ogden’s eye, and jerked my head towards the ladder.

“Up you get,” I whispered.

He eyed the trap-door coldly, then turned to me with an air of resolution.

“If you think you’re going to get me up there, you’ve another guess coming. I’m going to wait here till they get in, and let them take me. I’m about tired of this foolishness.”

It was no time for verbal argument. I collected him, a kicking handful, bore him to the ladder, and pushed him through the opening. He uttered one of his devastating squeals. The sound seemed to encourage the workers outside, like a trumpet-blast. The blows on the door redoubled.

I climbed the ladder, and shut the trap-door behind me.

The air of the loft was close and musty, and smelt of mildewed hay. It was not the sort of spot which one would have selected of one’s own free will to sit in for any length of time. There was a rustling noise, and a rat scurried across the rickety floor, drawing a startled yelp from Ogden. Whatever merits this final refuge might have as a stronghold, it was beyond question a noisome place.

The beating on the stable-door was working up to a crescendo. Presently there came a crash that shook the floor on which we sat and sent our neighbours, the rats, scuttling to and fro in a perfect frenzy of perturbation. The light of the automobile lamp poured in through the numerous holes and chinks which the passage of time had made in the old boards. There was one large hole near the centre which produced a sort of searchlight effect, and allowed us for the first time to see what manner of place it was in which we had entrenched ourselves. The loft was high and spacious. The roof must have been some seven feet above our heads. I could stand upright without difficulty.

In the proceedings beneath us there had come a lull. The mystery of our disappearance had not baffled the enemy for long, for almost immediately the rays of the lamp had shifted and began to play on the trap-door. I heard somebody climb the ladder, and the trap-door creaked gently as a hand tested it. I had taken up a position beside it, ready, if the bolt gave way, to do what I could with the butt of my pistol, my only weapon. But the bolt, though rusty, was strong, and the man dropped to the ground again. Since then, except for occasional snatches of whispered conversation, I had heard nothing.

Suddenly Sam’s voice spoke.

“Mr. Burns.”

I saw no advantage in remaining silent.

“Well?”

“Haven’t you had enough of this? You’ve given us a mighty good run for our money, but you can see for yourself that you’re through now. I’d hate like anything for you to get hurt. Pass the kid down, and we’ll call it off.”

He paused.

“Well?” he said “Why don’t you answer?”

“I did.”

“Did you? I didn’t hear you.”

“I smiled.”

“You mean to stick it out? Don’t be foolish, sonny. The boys here are mad enough at you already. What’s the use of getting yourself in the bad for nothing? We’ve got you in a pocket. I know all about that gun of yours, young fellow. I had a suspicion what had happened, and I’ve been into the house and found the shells you forgot to take with you. So, if you were thinking of making a bluff in that direction, forget it.”

The exposure had the effect I had anticipated.

“Of all the chumps!” exclaimed Ogden, caustically. “You ought to be in a home. Well, I guess you’ll agree to end this foolishness now? Let’s go down and get it over and have some peace. I’m getting pneumonia.”

“You’re quite right, Mr. Fisher,” I said. “But don’t forget I still have the pistol, even if I haven’t the shells. The first man who tries to come up here will have a headache to-morrow.”

“I shouldn’t bank on it, sonny. Come along, kiddo! You’re done. Be good, and own it. We can’t wait much longer.”

“You’ll have to try.”

Buck’s voice broke in on the discussion, quite unintelligible except that it was obviously wrathful.

“Oh, well!” I heard Sam say, resignedly, and then there was silence again below.

I resumed my watch over the trap-door, encouraged. This parleying, I thought, was an admission of failure on the part of the besiegers. I did not credit Sam with a real concern for my welfare—thereby doing him an injustice. I can see now that he spoke perfectly sincerely. The position, though I was unaware of it, really was hopeless, for the reason that, like most positions, it had a flank as well as a front. In estimating the possibilities of attack I had figured assault as coming only from below. I had omitted from my calculations the fact that the loft had a roof.

It was a scraping on the tiles above my head that first brought the new danger-point to my notice. There followed the sound of heavy hammering, and with it came a sickening realisation of the truth of what Sam had said. We were beaten.

I was too paralysed by the unexpectedness of the attack to form any plan; and, indeed, I do not think that there was anything that I could have done. I was unarmed and helpless.

I stood there, waiting for the inevitable.

Affairs moved swiftly. Plaster rained down on to the wooden floor. I was vaguely aware that the boy was speaking, but I did not listen to him.

A gap appeared in the roof, and widened. I could hear the heavy breathing of the man as he wrenched at the tiles.

And then the climax arrived, with anticlimax following so swiftly upon it that the two were almost simultaneous. I saw the worker on the roof cautiously poise himself in the opening, hunched up like some strange ape. The next moment he had sprung.

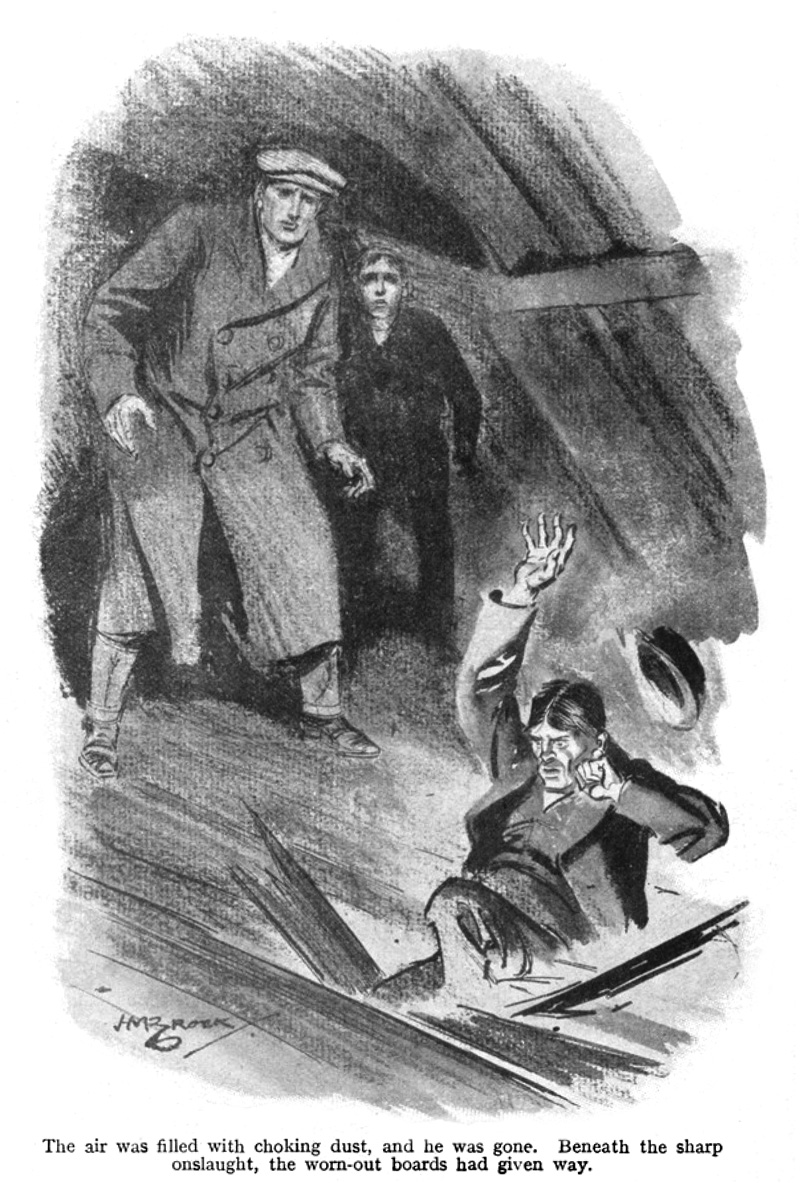

As his feet touched the

floor there came a rending, splintering crash; the air was filled with a

choking dust; and he was gone. The old worn-out boards had shaken under my tread.

They had given way in complete ruin beneath this sharp onslaught. The rays of

the lamp, which had filtered in little pencils of light through crevices, now

shone in a great lake in the centre of the floor.

As his feet touched the

floor there came a rending, splintering crash; the air was filled with a

choking dust; and he was gone. The old worn-out boards had shaken under my tread.

They had given way in complete ruin beneath this sharp onslaught. The rays of

the lamp, which had filtered in little pencils of light through crevices, now

shone in a great lake in the centre of the floor.

In the stable below all was confusion. Everybody was speaking at once. The hero of the late disaster was groaning noisily—for which he certainly had good reason. I did not know the extent of his injuries, but a man does not do that sort of thing with impunity.

The next of the strange happenings of the night now occurred.

I had not been giving Ogden a great deal of my attention for some time, other and more urgent matters occupying me. His action at this juncture, consequently, came as a complete and crushing surprise.

I was edging my way cautiously towards the jagged hole in the centre of the floor, in the hope of seeing something of what was going on below, when from close beside me his voice screamed: “It’s me, Ogden Ford. I’m coming”; and, without further warning, he ran to the hole, swung himself over, and dropped.

Manna falling from the skies in the wilderness never received a more whole-hearted welcome. Howls and cheers and ear-splitting whoops filled the air. The babel of talk broke out again. Some exuberant person found expression of his joy in emptying his pistol at the ceiling, to my acute discomfort, the spot he had selected as a target chancing to be within a foot of where I stood. Then they moved off in a body, still cheering.

CHAPTER XV

the happy ending

IN my recollections of that strange night there are wide gaps. Trivial incidents come back to me with extraordinary vividness; while there are hours of which I can remember nothing. What I did or where I went I cannot recall. It seems to me, looking back, that I walked about the school grounds without a pause till morning. I lost, I know, all count of time. I became aware of the dawn as something that had happened suddenly, as if light had succeeded darkness in a flash. It had been night. I looked about me, and it was day—a steely, cheerless day, like a December evening. And I found that I was very cold and very tired.

I sat down on the stump of a tree. I must have fallen asleep, for, when I raised my eyes again, the day was brighter. Its cheerlessness had gone. The sky was blue and birds were singing.

It must have been an hour later before the first beginnings of a plan of action came to me. It seemed to me that the only thing left to do was to go to London, find Mr. Abney, and report to him.

I turned to walk to the station. I could not guess even remotely what time it was. The sun was shining through the trees, but in the road outside the grounds there were no signs of workers beginning the day.

It was half-past five when I reached the station. A sleepy porter informed me that there would be a train to London at six.

I failed to find Mr. Abney. I inquired at his club, and was told that he had been there on the previous day, but not since then. I remained in London two days, calling at the club at intervals without success, and on the third returned to Sanstead. I could think of no other move.

It was about an hour after my return, and I was wandering about the grounds, trying to kill time, when there came the sound of automobile wheels on the gravel. A large red car was coming up the drive. It slowed down, and stopped beside me. There was only one passenger in the tonneau, a tall woman, smothered in furs. My main impression of her was of a pair of large, imperious eyes. That was all that there was of her, except furs.

I was given no leisure for wondering who she might be. Almost before the car had stopped she jumped out and clutched me by the arm, at the same time uttering this cryptic speech: “Whatever he offers I’ll double!”

She fixed me, as she spoke, with a commanding eye. She was a woman, I gathered in that instant, born to command. There seemed, at any rate, no doubt in her mind that she could command me. If I had been a black-beetle, she could not have looked at me with a more scornful superiority. Her eyes were very large and of a rich, fiery brown colour.

“Bear that in mind,” she went on. “I’ll double it if it’s a million dollars.”

“I’m afraid I don’t understand,” I said, finding speech.

She clicked her tongue impatiently.

“There’s no need to be so cautious and mysterious. I’m Mrs. Elmer Ford. I came here directly I got your letter. I think you’re the lowest sort of scoundrel that ever managed to keep out of gaol, but that needn’t make any difference just now. We’re here to talk business, Mr. Fisher, so we may as well begin.”

I was getting tired of being taken for Smooth Sam.

“My name is Burns,” I said.

“Alias Sam Fisher?”

“Not at all. Plain Burns. I am——”

Mrs. Ford interrupted me. She gave me the impression of being a woman who wanted a good deal of the conversation and who did not care how she got it. In a conversational sense, she thugged me at this point. Or, rather, she swept over me like some tidal wave, blotting me out.

“Mr. Burns?” she said, fixing her brown eyes, less scornful now, but still imperious, on mine. “I must apologise. I have made a mistake. I took you for a low villain of the name of Sam Fisher. I was to have met him at this exact spot, just about this time, by appointment; so, seeing you here, I mistook you for him.”

She stopped and raked me with her eyes, which said plainly, “If you are not Fisher, what earthly business have you here?”

“I am one of the assistant masters at the school,” I said.

“Yes?”

“Mr. Abney left me to look after your son while he was away.”

“Oh!”

She gave me a glance of unfathomable scorn.

“And you let this Fisher scoundrel steal him away from under your nose!” she said.

This was too much. I might be a worm, as her way of looking at me seemed to imply, but I felt the time had come to exercise a worm’s prerogative of turning. This was one of the most unpleasant women I had ever met, and I saw no necessity for trying to spare her feelings.

“May I describe the way in which I allowed your son to be stolen away from under my nose?” I said. And in well-chosen words I sketched the outline of what had happened. I did not omit to lay stress on the fact that Ogden’s departure with the enemy had been entirely voluntary.

She heard me out in silence.

“That was too bad of Oggie,” she said tolerantly, when I had ceased dramatically at the climax of my tale.

As a comment it seemed to me inadequate.

“Oggie was always high-spirited,” she went on. “No doubt you have noticed that?”

“A little.”

“He could be led, but never driven. With the best intention, no doubt, you refused to allow him to leave the stable that night and return to the house, and he resented the check and took the matter into his own hands.” She broke off, and looked at her watch. “Have you a watch? What time is it? Only that? I thought it must be later. I arrived too soon. I got a letter from this man Fisher, naming this spot and this hour for a meeting, when we could discuss terms. He said that he had written to Mr. Ford, appointing the same time.” She frowned. “I have no doubt he will come,” she said, coldly.

“Perhaps this is his car,” I said.

A second automobile was whirring up the drive. There was a shout as it came within sight of us, and the chauffeur put on the brake. A man sprang from the tonneau. He jerked a word to the chauffeur and the car went on up the drive.

He was a massively built man of middle age, with powerful shoulders and a face—when he had removed his motor-goggles—very like any one of half a dozen of those Roman emperors whose features have come down to us on coins and statues—square-jawed, clean-shaven, and aggressive. Like his wife (who was now standing, drawn up to her full height, staring haughtily at him), he had the airs of one born to command. The clashing of those wills must have smacked of a collision between the immovable mass and the irresistible force.

He met Mrs. Ford’s stare with one equally militant, then turned to me.

“I’ll give you double what she has offered you,” he said. He paused, and eyed me with loathing. “You scoundrel!” he added.

Custom ought to have rendered me immune to irritation, but it had not. I spoke my mind.

“One of these days, Mr. Ford,” I said, “I am going to publish a directory of the names and addresses of the people who have mistaken me for Smooth Sam Fisher. I am not Sam Fisher. Can you grasp that? My name is Burns, and I am a master at this school. And I may say that, judging from what I know of the little beast, anyone who kidnapped your son as long as two days ago will be so anxious to get rid of him that he will probably want to pay you for taking him back.”

My words almost had the effect of bringing this estranged couple together again. They made common cause against me.

“How dare you talk like that!” said Mrs. Ford. “Oggie is a sweet boy in every respect.”

“You’re perfectly right, Ruth,” said Mr. Ford. “He may want intelligent handling, but he’s a mighty fine boy.”

“I shall make inquiries, Elmer, and if this man has been ill-treating Oggie, I shall complain to Mr. Abney.”

“Quite right, Ruth.”

“I always opposed the idea of sending him away from home. If you had listened to me this would not have happened.”

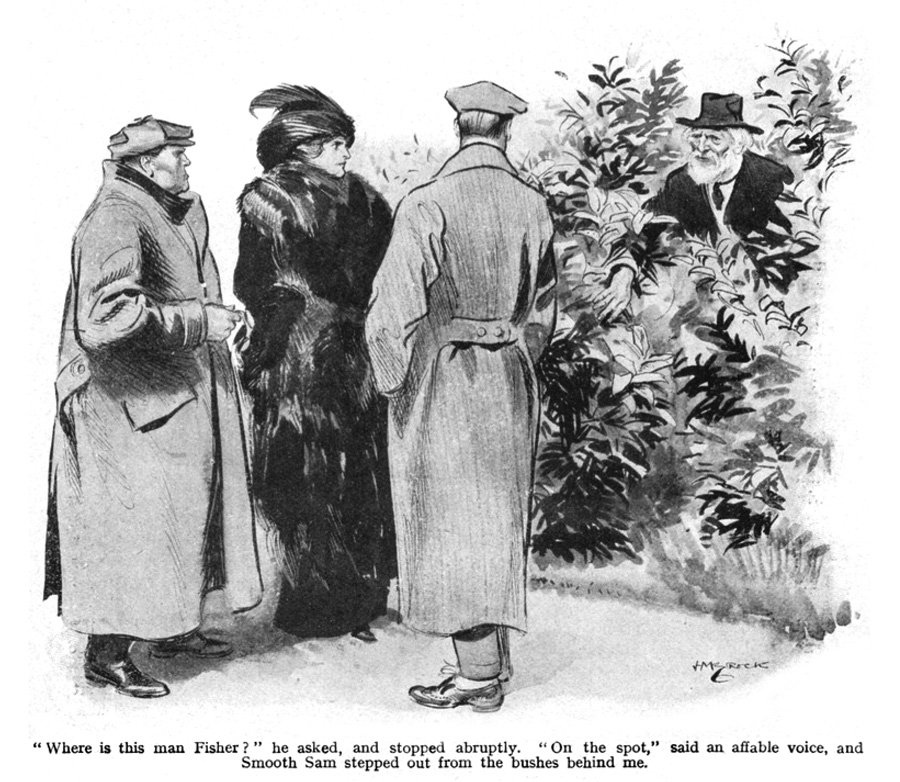

“I’m not sure you aren’t right. Where the dickens is this man Fisher?” he broke off abruptly.

“On the spot,” said an affable voice. The bushes behind me parted, and Smooth Sam stepped out on to the gravel.

I had recognised him by his voice. I certainly should not have done so by his appearance. He had taken the precaution of “making up” for this important meeting. A white wig of indescribable respectability peeped out beneath his black hat, his eyes twinkled from under two penthouses of white eyebrows. A white moustache covered his mouth. He was venerable to a degree.

He nodded to me, and bared his white head gallantly to Mrs. Ford.

“No worse for our little outing, Mr. Burns, I am glad to see. Mrs. Ford, I must apologise for my apparent unpunctuality, but I was not really behind time. I have been waiting in the bushes. I thought it just possible that you might have brought unwelcome members of the police force with you, and I have been scouting, as it were, before making my advance. I see, however, that all is well, and we can come at once to business. May I say, before we begin, that I overheard your recent conversation, and that I entirely disagree with Mr. Burns. Master Ford is a charming boy. Already I feel like an elder brother to him. I am loth to part with him.”

“How much?” snapped Mr. Ford. “You’ve got me. How much do you want?”

“I’ll give you double what he offers!” cried Mrs. Ford.

Sam held up his hand, his old pontifical manner intensified by the white wig.

“May I speak? Thank you. This is a little embarrassing. When I asked you both to meet me here, it was not for the purpose of holding an auction. I had a straightforward business proposition to make to you. It will necessitate a certain amount of plain and somewhat personal speaking. May I proceed? Thank you. I will be as brief as possible.”

His eloquence appeared to have had a soothing effect on the two Fords. They remained silent.

“You must understand,” said Sam, “that I am speaking as an expert. I have been in the kidnapping business many years, and I know what I am talking about. And I tell you that the moment you two separated, you said good-bye to all peace and quiet. Bless you”—Sam’s manner became fatherly—“I’ve seen it a hundred times. Couple separate, and, if there’s a child, what happens? They start in playing battledore-and-shuttlecock with him. Wife sneaks him from husband. Husband sneaks him back from wife. After a while, along comes a gentleman in my line of business, a professional at the game, and he puts one across on both the amateurs. He takes advantage of the confusion, slips in, and gets away with the kid. That’s what has happened here, and I’m going to show you the way to stop it another time. Now I’ll make you a proposition. What you want to do”—I have never heard anything so soothing, so suggestive of the old family friend healing an unfortunate breach, as Sam’s voice at this juncture—“what you want to do is to get together again right quick. Never mind the past. Let bygones be bygones.”

A snort from Mr. Ford checked him for a moment, but he resumed.

“I guess there were faults on both sides. Get together and talk it over. And when you’ve agreed to call the fight off and start fair again, that’s where I come in. Mr. Burns here will tell you, if you ask him, that I’m anxious to quit this business and marry and settle down. Well, see here. What you want to do is to give me a salary—we can talk figures later on—to stay by you and watch over the kid. Don’t snort—I’m talking plain sense. You’d a sight better have me with you than against you. Set a thief to catch a thief. What I don’t know about the fine points of the game isn’t worth knowing. I’ll guarantee, if you put me in charge, to see that nobody comes within a hundred miles of the kid unless he has an order-to-view. You’ll find I earn every penny of that salary. Mr. Burns and I will now take a turn up the drive while you think it over.”

He linked his arm in mine, and drew me away. As we turned the corner of the drive I caught a glimpse over my shoulder of Ogden’s parents. They were standing where we had left them, as if Sam’s eloquence had rooted them to the spot.

“Well, well, well, young man,” said Sam, eyeing me affectionately, “it’s pleasant to meet you again, under happier conditions than last time. You certainly have all the luck, sonny, or you would have been badly hurt that night. I was getting scared how the thing would end. Buck’s a plain rough-neck, and his gang are as bad as he is, and they had got mighty sore at you—mighty sore. If they had grabbed you there’s no knowing what might not have happened. However, all’s well that ends well, and this little game has surely had the happy ending. I shall get that job, sonny. Old man Ford isn’t a fool, and it won’t take him long, when he gets to thinking it over, to see that I’m right. He’ll hire me.”

“Aren’t you rather reckoning without your partner?” I said. “Where does Buck Macginnis come in on the deal?”

Sam patted my shoulder paternally.

“He doesn’t, sonny, he doesn’t. It was a shame to do it—it was like taking candy from a kid—but business is business. I was reluctantly compelled to double-cross poor old Buck. I sneaked the kid away from him next day. It’s not worth talking about; it was too easy. Buck’s all right in a rough-and-tumble, but when it comes to brains he gets left, and so he’ll go on through life, poor fellow. I hate to think of it.”

He sighed. Buck’s misfortunes seemed to move him deeply.

“I shouldn’t be surprised if he gave up the profession after this. He has had enough to discourage him. I told you about what happened to him that night, didn’t I? No? I thought I had. Why, Buck was the guy who did the high dive through the roof; and, when we picked him up, we found he’d broken his leg again! Isn’t that enough to jar a man? I guess he’ll retire from the business after that. He isn’t intended for it.”

* * * * *

We were approaching the two automobiles now; and, looking back, I saw Mr. and Mrs. Ford walking up the drive. Sam followed my gaze, and I heard him chuckle.

“It’s all right,” he said. “They’ve fixed it up. Something in the way they’re walking tells me they’ve fixed it up.”

“Jarvis,” she said to the chauffeur, “take the car home. I shan’t need it any more. I am going with Mr. Ford.”

She stretched out a hand towards the millionaire. He caught it in his, and they stood there, smiling foolishly at each other, while Sam, almost purring, brooded over them like a stout fairy queen. The two chauffeurs looked on woodenly.

Mr. Ford released his wife’s hand, and turned to Sam.

“Fisher!”

“I’ve been considering your proposition. There’s a string tied to it.”

“Oh, no, sir. I assure you!”

“There is. What guarantee have I that you won’t double-cross me?”

Sam smiled, relieved.

“You forget that I told you that I was about to be married, sir. My wife won’t let me!”

Mr. Ford waved his hand towards the automobile.

“Jump in,” he said, briefly. “And tell him where to drive to. You’re engaged!”

The End

Wodehouse expanded this story into the novel The Little Nugget, adding a love interest for Peter Burns.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums