The Captain, September 1903

IV.

SHALL go, Babe,” said Charteris, on the following night.

SHALL go, Babe,” said Charteris, on the following night.

The Sixth form had a slack day before them on the morrow, there being that temporary lull in the form-work which occurred about once a week, when there was no composition of any kind to be done. The Sixth did four compositions a week, two Greek and two Latin, and except for these did not bother itself much about overnight preparation. The Latin authors which the form was doing this term were Vergil and Livy, and when either of these was on the next day’s programme, most of the Sixth considered that they were justified in taking a night off. They relied on their ability to translate either of the authors at sight and without previous acquaintance. The popular notion that Vergil is hard rarely appeals to a member of a public school. There are two ways of translating Vergil, the conscientious and the other. He chooses the other.

On this particular night, therefore, work was “off.” Merevale was over at the Great Hall, taking preparation, and the sixth form Merevalians had assembled in Welch’s study to talk about things in general. It was after a pause of some moments that had followed upon a lively discussion of the house’s prospects in the forthcoming finals that Charteris had spoken.

“I shall go,” he said.

“Go where?” asked Tony from inside a deck chair.

“Babe knows.”

The Babe turned to the company and explained.

“The lunatic says he’s going in for the Strangers’ Mile or some other equally futile race at some sports at Rutton next week. He’ll get booked for a cert. He can’t see that. I never saw such a man.”

“Rally round,” said Charteris, “and reason with me. I’ll listen. Tony, what do you think about it?”

Tony expressed his opinion tersely, and Charteris thanked him. Welch, who had been reading a book, now awoke to the fact that a discussion was in progress, and asked for details. The Babe explained once more, and Welch heartily corroborated Tony’s remarks. Charteris thanked him, too.

“You aren’t really going, are you?” asked Welch.

“Rather.”

“The Old Man won’t give you leave.”

“I shan’t worry the Old Man about it.”

“But it’s miles out of bounds. Stapleton station is out of bounds, to begin with. It’s against rules to go in a train, and Rutton is even more out of bounds than Stapleton.”

“And as there are sports there,” said Tony, “the Old Man is certain to put Rutton specially out of bounds for that day. He always bars a St. Austin’s chap going to a place when there’s anything of that sort on there.”

“Don’t care. What have I to do with the Old Man’s petty prejudices? Now, let me get at my time-table. Here we are. Now then.”

“Don’t be a fool,” said Tony.

“As if I should. Look here, there is a train that starts from Stapleton at three. I can catch that all right. Gets to Rutton at three-twenty. Sports begin at three-fifteen. At least, they are supposed to. Over before five, I should think. At any rate, my race ought to be. Though—I was forgetting—I must stop to see the Oldest Inhabitant’s nevvy win the egg and spoon canter. But that ought to come on before the Strangers’ race. Train back at a quarter past five. Arrives at a quarter to six. Lock up six fifteen. That gives me half an hour to get here from Stapleton. What more do you want? Consider the thing done. And I should think the odds against my being booked are twenty-five to one, at which price, if any gent present cares to deposit his money, I am willing to take him.”

“You won’t go,” said Welch. “I’ll bet you anything you like you won’t go.”

That settled Charteris. The visit to Rutton, hitherto looked upon as more or less of a pleasure, became now a solemn duty. One of Charteris’ mottoes for everyday use was “Let not thyself be scored off by Welch.”

“That’s all right,” he said, “of course I shall go.”

The day of the sports arrived, and the Babe, meeting Charteris at Merevale’s gate, made a last attempt to head him off from his purpose.

“How are you going to take your things?” he asked. “You can’t carry a bag. The first beak you met would ask questions.”

Charteris patted a bloated coat pocket.

Charteris patted a bloated coat pocket.

“Bags,” he said, laconically. “Vest,” he added, doing the same to the other pocket. Shoes,” he concluded, “you will observe I am carrying in a handy brown paper parcel, and if anybody wants to know what’s in it, I shall tell him it’s acid drops. Sure you won’t come, too?”

“I’m not such an ass,” quoth the Babe.

“All right. So long, then. Be good while I’m gone.”

And he passed on down the road to Stapleton.

The Rutton New Recreation Grounds presented, as the Stapleton Herald justly remarked in its next week’s issue, “a gay and animated appearance.” There was a larger crowd than Charteris had expected. He made his way through them, resisting without difficulty the entreaties of a hoarse gentleman in a check suit to have three to two on ’Enery Something for the hundred yards, and came at last to the dressing tent.

At this point it occurred to him that it would be judicious to find out when his race was to start. It was rather a chilly day, and the less of it that he spent in the undress uniform of shorts the better. He bought a correct card for twopence, and scanned it. The Strangers’ Mile was down for four-fifty. There was no need to change for an hour yet. He wished the authorities could have managed to date the event earlier. Four-fifty was running it rather fine. The race would be over, allowing for unpunctuality, by about five to five, and it was a walk of some ten minutes to the station, less if he hurried. That would give him ten minutes for recovering from the effects of the race, and changing back into his ordinary clothes again. It would be quick work. But the trains on that line were always late—it was one of the metropolitan improvements which had recently been introduced into Arcadia—and, having come so far, he was not inclined to go back without running in the race. He would never be able to hold up his head again if he did that. He left the dressing-tent, and started on a tour of the field.

The scene was quite different from anything he had ever witnessed before in the way of sports. The sports at St. Austin’s were decorous to a degree. These leaned more to the rollickingly convivial. It was like an ordinary country race-meeting, except that men were running instead of horses. Rutton was a quiet little place for the majority of the year, but on this day it woke up, and was evidently out to enjoy itself. The Rural Hooligan was a good deal in evidence, and though he was comparatively quiet just at present, the frequency with which he visited the various refreshment stalls that dotted the ground gave promise of livelier times in the future. Charteris felt that the afternoon would not be dull. The hour soon passed, and Charteris, having first seen the Oldest Inhabitant’s nevvy romp home in the egg and spoon event, took himself off to the dressing tent, and began to get into his running-clothes. The bell for the race was just ringing when he left the tent. He trotted over to the starting-place. Apparently there was not a very large “field.” Two weedy youths of Charteris’ age had put in an appearance, and a very tall, thin man, dressed in blushing pink, came up immediately afterwards. Charteris had just removed his coat, and was about to get to his place on the line, when another competitor arrived, and to judge by the applause that greeted his advent he was evidently a favourite in the locality. It was with a shock that Charteris recognised his old acquaintance, the Bargees’ secretary.

He was clad in running clothes of a bright orange and a smile of conscious superiority, and when somebody in the crowd called out “Go it, Jarge,” he accepted the tribute as his due, and waved a condescending hand in the speaker’s direction.

Some moments elapsed before he caught sight of Charteris, and the latter had time to decide on his line of action. If he attempted concealment in any way, the man would recognise that on this occasion, at any rate, he had, to use an adequate if unclassical expression, got the bulge, and then there would be trouble. By brazening things out, however, there was just a chance that he might make him imagine that there was more in the matter than met the eye, and that in some way he had actually obtained leave to visit Rutton that day. After all, the man didn’t know very much about school rules, and the recollection of the recent fiasco in which he had taken part would make him think twice about playing the amateur policeman again, especially in connection with Charteris.

So he smiled genially, and expressed a hope that the man enjoyed robust health.

The man replied by glaring in a simple and unaffected manner.

“Looked up the headmaster lately?” asked Charteris.

“What are you doing here?”

“I’m going to run. Hope you don’t mind.”

“You’re out of bounds.”

“That’s what you said before. You’d better enquire a bit before you make rash statements. Otherwise there’s no knowing what may not happen. Perhaps Mr. Dacre has given me leave.”

The man said something objurgatory under his breath, but forebore to continue the discussion. He was wondering, as Charteris had expected that he would, whether the latter had really got leave or not. It was a difficult problem. Whether such a result was due to his mental struggles or whether it was simply to be attributed to his poor running is open to question, but the fact remains that the secretary of the Old Crockfordians did not shine in the Strangers’ Mile. He came in last but one, vanquishing the pink sportsman by a foot. Charteris, after a hot finish, was beaten on the tape by one of the weedy youths, who exhibited astonishing powers of sprinting in the last hundred and fifty yards, overhauling Charteris, who had led all the time, in fine style, and scoring what the Stapleton Herald described as a “highly popular victory.”

As soon as he had recovered his normal stock of wind—which was not immediately—it was borne in upon Charteris that if he wanted to catch the five-fifteen back to Stapleton, he had better be beginning to change. He went to the dressing-tent, and on examining his watch was horrified to find that he had just ten minutes in which to do everything. And the walk to the station, he reflected, was a long five minutes. He hurled himself into his clothes, and, disregarding the Bargee, who had entered the tent and seemed to wish to continue the conversation at the point at which they had left off, shot away towards the nearest gate. He had exactly four minutes and twenty-five seconds for the journey, and he had just run a mile.

V.

ORTUNATELY

the road was mainly level. On the other hand, he

was handicapped by an overcoat. After the first hundred yards he took this off,

and carried it in an unwieldy parcel. This, he found, was an improvement and

running became easier. He had worked the stiffness out of his legs by this

time, and was going well. Three hundred yards from the station it was anybody’s

race. The exact position of the other competitor, the train, could not be

defined. It was, at any rate, not within earshot, which meant that it had still

a quarter of a mile to go. Charteris considered that he had earned a rest. He

slowed down to a walk, but after proceeding at this pace for a few yards

thought that he heard a distant whistle, and dashed on again. Suddenly a

raucous bellow of laughter greeted his ears from a spot in front of him, hidden

from his sight by a bend in the road.

ORTUNATELY

the road was mainly level. On the other hand, he

was handicapped by an overcoat. After the first hundred yards he took this off,

and carried it in an unwieldy parcel. This, he found, was an improvement and

running became easier. He had worked the stiffness out of his legs by this

time, and was going well. Three hundred yards from the station it was anybody’s

race. The exact position of the other competitor, the train, could not be

defined. It was, at any rate, not within earshot, which meant that it had still

a quarter of a mile to go. Charteris considered that he had earned a rest. He

slowed down to a walk, but after proceeding at this pace for a few yards

thought that he heard a distant whistle, and dashed on again. Suddenly a

raucous bellow of laughter greeted his ears from a spot in front of him, hidden

from his sight by a bend in the road.

“Somebody slightly tight,” thought he, rapidly diagnosing the case. “By Jove, if he comes rotting about with me, I’ll kill him and jump on his body.” Having to do anything in a desperate hurry always upset Charteris’ temper. He turned the corner at a sharp trot, and came upon two youths who seemed to be engaged in the harmless occupation of trying to ride a bicycle. They were of the type which he held in especial aversion, the Rural Hooligan type, and one at least of the two had evidently been present at a recent circulation of the festive bowl. He was wheeling the bicycle about the road in an aimless way, and looked as if he wondered what was the matter with it, in that it would not keep still for two consecutive seconds. The other youth was apparently of the “Charles-his-friend” variety, content to look on and applaud, and generally play chorus to his companion’s “lead.” He was standing at the side of the road smiling broadly in a way that argued feebleness of mind. Charteris was not sure which of the two he hated most at sight. He was inclined to call it a tie. However, there seemed to be nothing particularly lawless in what they were doing now. If they were content to let him pass without hindrance, he for his part was prepared generously to overlook the insult they offered him by existing at all, and to maintain a state of truce.

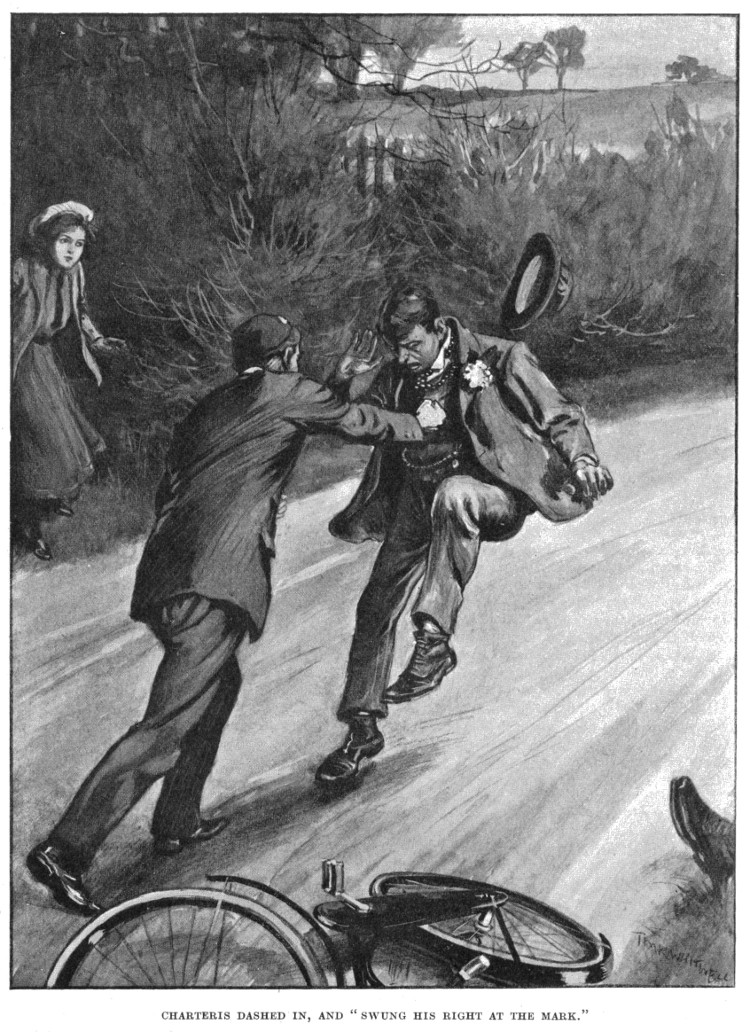

But, as he drew nearer, he saw that there was more in the business than the casual spectator might at first have supposed. A second and keener inspection of the reptiles revealed fresh phenomena. In the first place, the bicycle which Hooligan number one was playing with was a lady’s bicycle, and a small one at that. Now, up to the age of fourteen and the weight of ten stone, a beginner at cycling often finds it more convenient to learn to ride on a lady’s machine than on a gentleman’s. The former offers greater facilities for dismounting, a quality not to be despised in the earlier stages of initiation. But, though this was undoubtedly the case, and though Charteris knew that it was so, yet he felt instinctively that there was something wrong here. Hooligans of eighteen years and twelve stone do not learn to ride on small ladies’ machines. Or, if they do, it is probably without the permission and approval of the small ladies who own the same. Valuable as his time was, Charteris felt that it behoved him to devote a thoughtful minute or two to the examining of this affair. He slowed down once again to a walk, and as he did so his eye fell upon the one character in the drama whose absence had puzzled him—the owner of the bicycle. And he came to the conclusion that life would be a hollow mockery if he failed to fall upon those revellers, and slay them. She stood by the hedge on the right, a forlorn little figure in grey, and she gazed sadly and hopelessly at the manœuvres that were going on in the middle of the road. Her age Charteris estimated at a venture at twelve—a correct guess. Her state of mind he also conjectured. She was letting “I dare not” wait upon “I would,” like the late M‘Beth, the cat i’ the adage, and other celebrities. She evidently had plenty of remarks to make on the subject in hand, but refrained from motives of prudence.

Charteris had no such scruples. The feeling of fatigue that had been upon him had vanished, and his temper, which had been growing more and more villainous for some twenty minutes, now boiled over enthusiastically at the sight of something tangible to work itself off upon. Even without a cause he detested the Rural Hooligan. Now that a real, registered motive for this antipathy had been supplied, he felt capable of dealing with a whole regiment of the breed. He would have liked to have committed a murder, but assault and battery would do at a pinch.

The being with the bicycle had just let it fall with a crash to the ground, when Charteris went for him low, in the style which the Babe always insisted on seeing in members of the first fifteen on the football field, and hove him without comment into a damp ditch. “Charles-his-friend” uttered a shout of disapproval, and rushed into the fray. Charteris gave him the straight left, of the type to which the great John Jackson is said to have owed so much in the days of the old Prize Ring, and Charles, taking it between the eyes, stopped in a discontented and discouraged manner, and began to rub the place. Whereupon Charteris dashed in, and, to use an expression suitable to the deed, “swung his right at the mark.” The “mark,” it may be explained for the benefit of the non-pugilistic, is that portion of the human form divine which lies hid behind the third button of the waistcoat. It covers—in a most inadequate way—the wind, and even a gentle tap in the locality is apt to produce a fleeting sense of discomfort. A genuine flush hit on the spot, shrewdly administered by a muscular arm with the weight of the body behind it, causes the passive agent in the transaction to wish fervently, as far as he is at the moment physically capable of wishing anything, that he had never been born. Charles collapsed like an empty sack, and Charteris, getting a grip of the outlying portions of his costume, rolled him into the ditch on top of his companion, who had just recovered sufficiently to be thinking of getting out again.

Charteris picked up the bicycle, and gave it a cursory examination. The enamel was a good deal scratched, but no material damage had been done. He wheeled it across to its owner. He would have felt more like a St. George after an interview with the Dragon if he had not, in tackling Hooligan number one, contrived to cover his face with rich mud from the ditch. He could not help feeling that it detracted from the general romance of the thing.

“It isn’t much hurt,” he said, as they walked on together down the road; “bit scratched, that’s all.”

“Thanks, awfully,” said the small lady.

“Oh, not at all,” said Charteris, “I enjoyed it.” (He felt that he had said the correct thing here.) “I’m sorry those chaps frightened you.”

“They did rather. But”—triumphantly—“I didn’t cry.”

“Rather not,” said Charteris, “you were awfully plucky. I noticed at the time. But hadn’t you better ride on? Which way were you going?”

“I wanted to get to Stapleton.”

“Oh. That’s simple enough. You’ve merely got to go straight on down this road. As straight as ever you can go. But, look here, you know, you shouldn’t be out alone like this. It isn’t safe. Why did they let you?”

The lady avoided his eye. She bent down and inspected the left pedal.

“They shouldn’t have sent you out alone,” said Charteris; “why did they?”

“They didn’t. I came.”

There was a world of meaning in the phrase. Charteris was in the same case. They had not let him. He had come. Here was a kindred spirit, another revolutionary soul, scorning the fetters of convention and the so-called authority of self-constituted rulers, aha! Bureaucrats!

“Shake hands,” he said, “I’m in just the same way.”

They shook hands gravely.

“You know,” said the lady, “I’m awfully sorry I did it now. It was very naughty.”

“I’m not sorry yet,” said Charteris, “but I expect I shall be soon.”

“Will you be sent to bed?”

“I don’t think so.”

“Will you have to learn beastly poetry?”

“I hope not.”

She would probably have gone on to investigate things further, but at that moment there came the faint sound of a whistle. Then another, closer this time. Then a faint rumbling, which increased in volume steadily.

Charteris looked back. The line ran by the side of the road. He could see the smoke of a train through the trees. It was quite close now. And he was still nearly two hundred yards from the station gates.

“I say,” he said, “Great Scott, here comes my train. I must rush. Goodbye. You keep straight on.”

His legs had had time to grow stiff again. For the first few strides running was painful. But his joints soon adapted themselves to the strain, and in ten seconds he was running as fast as he had ever run off the track. When he had travelled a quarter of the distance, the small cyclist overtook him.

“Be quick,” she said. “It’s just in sight.”

Charteris quickened his stride, and, paced by the bicycle, spun along in fine style. Forty yards from the station the train passed him. He saw it roll into the station. There were still twenty yards to go, exclusive of the station steps, and he was already running as fast as he knew how. Now there were only ten. Now five. And at last, with a hurried farewell to his companion, he bounded up the steps and on to the platform. At the end of the platform the line took a sharp curve to the right. Round that curve the tail-end of the guard’s van was just disappearing.

“Missed it, sir,” said the solitary porter who managed things at Rutton, cheerfully. He spoke as if he were congratulating Charteris on having done something remarkably clever.

“What’s the next?”

“Eight-thirty,” was the porter’s appalling reply.

For a moment Charteris felt quite ill. No train till eight-thirty! Then was he, indeed, lost. But it couldn’t be true. There must be some sort of a train between now and then.

“Are you certain?” he said; “surely there’s a train before that.”

“Why, yes, sir,” said the porter, gleefully, “but they be all uxpresses. Eight-thirty be the only ’un what starps at Rooton.”

“Thanks,” said Charteris, with marked gloom, “I don’t think that will be much good to me. My aunt, what a hole I’m in.”

The porter made a sympathetic and interrogative noise at the back of his throat, as if inviting him to confess all. But Charteris felt unequal to the intellectual pressure of conversations with porters. There are moments when one wants to be alone.

He went down the stops again. When he got into the road, his small cycling friend had vanished. He envied her. She was doing the journey comfortably on a bicycle. He would have to walk it. Walk it! He didn’t believe he could. The Strangers’ Mile, followed by the Homeric combat with the two Bargees, and the ghastly sprint to wind up with, had left him unfit for further feats of pedestrianism. And it was eight miles to Stapleton, if it was a yard, and another mile from Stapleton to St. Austin’s. Charteris, having once more invoked the name of his aunt, pulled himself together with an effort and limped gallantly in the direction of Stapleton.

But Fate, so long hostile, at last relented. A rattle of wheels approached him from behind. A thrill of hope shot through him at the sound. There was a prospect of a lift. He stopped, and waited for the dog-cart—it sounded like a dog-cart—to arrive. Then he uttered a yell of triumph, and began to wave his arms like a semaphore. The man in the dog-cart was Adamson.

“Hullo, Charteris,” said the doctor, pulling up, “what are you doing here? What’s happened to your face? It’s in a shocking state.”

“Only mud,” said Charteris; “good, honest English mud, borrowed from a local ditch. It’s a long yarn. Can I get up?”

“Come along. Plenty of room.”

Charteris climbed up, and sank on to the cushioned seat with a sigh of pleasure. What glorious comfort. He had seldom enjoyed anything so much in his life.

“I’m nearly dead,” he said, as the dog-cart went on again, “This is how it all happened. You see, it was this way——”

And he began forthwith upon a brief synopsis of his adventures.

VI.

Y

special request the doctor dropped Charteris within a

hundred yards of Merevale’s door.

Y

special request the doctor dropped Charteris within a

hundred yards of Merevale’s door.

“Good-night,” he said. “I don’t suppose you value my advice at all, but you may have it for what it is worth. I recommend you to stop this sort of game. Next time something will happen.”

“By Jove, yes,” said Charteris, climbing painfully down from his seat. “I’ll take that advice. I’m a reformed character from now onwards. It isn’t good enough. Hullo, there’s the bell for lock-up. Good-night, doctor, and thanks most awfully for the lift. It was awfully kind of you.”

“Don’t mention it,” said Dr. Adamson. “It is always a privilege to be in your company. When are you coming to tea with me again?”

“Whenever you’ll have me. I shall get leave this time. It will be quite a novel experience.”

“Yes. By the way, how’s Graham? It is Graham, isn’t it? The youth who broke his collarbone.”

“Oh, he’s getting on splendidly. But I must be off. Good-night.”

“Good-night. Come next Monday, if you can.”

“Right. Thanks awfully.”

He hobbled in at Merevale’s gate, and went up to his study. The Babe was in there talking to Welch. You could generally reckon on finding the Babe talking to someone. He was of a sociable disposition.

“Hullo,” he said. “Here’s Charteris.”

“What’s left of him,” said Charteris.

“How did it go off?”

“Don’t talk about it.”

“Did you win?” asked Welch.

“No. Second. By a yard. Jove! I’m dead.”

“Hot race?”

“Rather. It wasn’t that, though. I had to sprint all the way to the station, and missed my train by a couple of seconds at the end of it all.”

“Then how did you get here?”

“That was my one stroke of luck. I started to walk back, and after I’d gone about a quarter of a mile, Adamson caught me up in his dog-cart. I suggested that it would be a Christian act on his part to give me a lift, and he did. I shall remember Adamson in my will.”

“How did you lose?” enquired the Babe.

“The other man beat me. But for that I should have won hands down. Oh, I say, guess who I met at Rutton?”

“Not a master?”

“Almost as bad. The Bargee man who paced me from Stapleton. (Have I ever told you about that affair?) Man who crocked Tony, you know.”

“Great Scott,” said the Babe, “did he recognise you?”

“Rather. We had a long and very pleasant conversation.”

“If he reports you—” began the Babe.

“Who’s that?”

Tony had entered the study.

“Hullo, Tony. Adamson told me to remember him to you.”

“So you’ve got back?”

Charteris confirmed the hasty guess.

“But what are you talking about, Babe?” said Tony. “Who’s going to be reported, and who’s going to report?”

The Babe briefly explained the situation.

“If the man,” he said, “reports Charteris, he may get run in to-morrow, and then we shall have both our halves away against Dacre’s. Charteris, you are an ass to go rotting about out of bounds like this.”

“Nay, dry the starting tear,” said Charteris, cheerfully. “In the first place I shouldn’t get kept in on a Thursday, were it ever so. I should get shoved into extra on Saturday. Also I shrewdly conveyed to the Bargee the impression that I was at Rutton by special permission.”

“He’s bound to know that can’t be true,” said Tony.

“Well, I told him to think it over. You see, he got so badly left last time he tried to drop on me—have I told you about that business, by the way?—that I shouldn’t be a bit surprised if he let me alone this trip.”

“Let’s hope so,” said the Babe with gloom.

“That’s right, Babby,” remarked Charteris encouragingly, “you buck up and keep looking on the bright side. It’ll be all right, you see if it won’t. If there’s any running in to be done, I shall do it. I shall be frightfully fit to-morrow after all this dashing about to-day. I haven’t an ounce of adipose deposit on me. Upon my word, it seems to me unpardonable vanity, and worse than that, to call one’s fat an adipose deposit. I’m a fine, strapping specimen of sturdy young English manhood. And I’m going to play a very selfish game to-morrow, Babe.”

“Oh, my dear chap, you mustn’t.” The Babe’s face wore an expression of pain and horror. The success of the house team in the final was very near to his heart. He could not understand anyone jesting on the subject. Charteris respected his anguish, and relieved it speedily.

“I was only ragging,” he said; “considering that we’ve got no chance of winning except through our three-quarters, I’m not likely to keep the ball from them, if I get a chance of getting it out. Make your mind easy, Babe.”

The final house match was always a warmish game. The rivalry between the various houses was great, and the football cup especially was fought for with immense keenness. Also, the match was the last fixture of the season, and there was a certain feeling in the teams that if they did happen to injure a man or two it would not much matter. The disabled sportsmen would not be needed for school match purposes for another six months. As a result of which philosophical reflection the tackling ruled slightly energetic, and the handing-off was done with vigour.

This year, to add a sort of finishing touch, there was just a little ill-feeling between Dacre’s and Merevale’s. The cause of it was the Babe. Until the beginning of the term he had been a day-boy. Then the news began to circulate that he was going to become a boarder, either at Dacre’s or at Merevale’s. He chose the latter, and Dacre’s felt aggrieved. Some of the less sportsmanlike members of the house had proposed that a protest should be made against his being allowed to play, but, fortunately for the credit of the house, Prescott, the captain of Dacre’s fifteen, had put his foot down with an emphatic bang at the suggestion. As he had sagely pointed out, there were some things which were bad form, and this was one of them. If the team wanted to express their disapproval, said he, let them do it on the field by tackling their very hardest. He personally was going to do his best in that direction, and he advised them to do the same.

The rumour of this bad blood had got about the school, and when Swift, Merevale’s only first fifteen forward, kicked off up hill, a large crowd was lining the ropes. It was evident from the first that it would be a good game. Dacre’s were the better side as a team. They had no really weak spot. But Merevale’s extraordinarily strong three-quarter line made up for an inferior scrum. And the fact that the Babe was in the centre was worth much.

Dacre’s pressed at first. Their pack was unusually heavy for a house-team, and they made full use of it. They took the ball down the field in short rushes till they were in Merevale’s twenty-five. Then they began to heel, and if things had been more or less exciting for the Merevalians before, they became doubly so now. The ground was dry, and so was the ball, and the game consequently waxed fast. Time after time the ball went along Dacre’s three-quarter line, only to end by finding itself hurled, with the wing who was carrying it, into touch. Occasionally the centres, instead of feeding their wings, would try to get through themselves. And that was where the Babe came in. He was admittedly the best tackler in the school, but on this occasion he excelled himself. His normally placid temper had been ruffled early in the game by his being brought down by Prescott, and this had added a finish to his methods. His man never had a chance of getting past.

At last a lofty kick into touch over the heads of the spectators gave the teams a few seconds rest.

The Babe went up to Charteris.

“Look here,” he said, “it’s risky, but I think we’ll try having the ball out a bit.”

“In our own twenty-five?”

“Wherever we are. I believe it will come off all right. Anyway, we’ll try it. Tell the forwards.”

So Charteris informed the forwards that they were to let it out, an operation which, for forwards playing against a pack much heavier than themselves, it is easier to talk about than perform. The first half-dozen times that Merevale’s scrum tried to heel, they were shoved off their feet, and it was on the enemy’s side that the ball came out. But the seventh attempt succeeded. Out it came, cleanly and speedily. Daintree, who was playing half instead of Tony, switched it across to Charteris. Charteris dodged the half who was marking him, and ran. Heeling and passing in one’s own twenty-five is like smoking—an excellent habit if indulged in in moderation. On this occasion it answered perfectly. Charteris ran to the half-way line, and handed the ball on to the Babe. The Babe was tackled from behind, and passed to Thomson. Thomson dodged his man, and passed to Welch. Welch was the fastest sprinter in the school. It was a pleasure—if you did not happen to be on the opposing side—to see him race down the touch-line. He was off like an arrow. Dacre’s back made a futile attempt to get at him. Welch could have given him twelve yards in a hundred. He ran round him in a large semicircle, and, amidst howls of rapture from the Merevalians in the audience, scored between the posts. The Babe took the kick, and converted without difficulty. Five minutes afterwards the whistle blew for half-time.

The remainder of the game was fought out on the same lines. Dacre’s pressed nearly all the time, and scored an unconverted try, but twice the ball came out on Merevale’s side and went down their line. Once it was the Babe, who scored with a run from his own goal-line, and once Charteris, who got it from halfway, dodging through the whole team. The last ten minutes of the match was marked by a slight excess of energy on both sides. Dacre’s forwards were in a murderous frame of mind, and fought like demons to get through, and Merevale’s played up to them with spirit. The Babe seemed continually to be precipitating himself at the feet of rushing forwards, and Charteris felt as if at least a dozen bones were broken in various parts of his body. The game ended on Merevale’s line, but they had won the match and the cup by two goals and a try to a try.

Charteris limped off the field, cheerful but damaged. He ached all over, and there was a large bruise on his left cheek-bone, a souvenir of a forward rush in the first half. Also he was very certain that he was not going to do a stroke of work that night.

He and the Babe were going to the house, when they were aware that the Headmaster was beckoning to them.

“Well, MacArthur, and what was the result of the match?”

“We won, sir,” beamed the Babe. “Two goals and a try to a try.”

“You have hurt your cheek, Charteris.”

“Yes, sir.”

“How did you do that?”

“I got a kick, sir, in one of the rushes.”

“Ah. I should bathe it, Charteris. Bathe it well. I hope it will not be painful. Bathe it well in warm water.”

He walked on.

“You know,” said Charteris to the Babe, as they went into the house, “the Old Man isn’t such a bad sort, after all. He has his points, don’t you think so?”

The Babe said that he did.

“I’m going to reform, you know,” said Charteris, confidentially.

“It’s about time. You can have the first bath, if you like. Only buck up.”

Charteris boiled himself for ten minutes, and then dragged his weary limbs to his study. It was while he was sitting in a deck-chair, eating mixed biscuits, that Master Crowinshaw, his fag, appeared.

“Well?” said Charteris.

“The Head told me to tell you that he wanted to see you at the School House as soon as you can go.”

“All right,” said Charteris; “thanks.”

“Now what,” he continued to himself, “does the Old Man want to see me for? Perhaps he wants to make certain that I’ve bathed my cheek in warm water. Anyhow, I suppose I must go.”

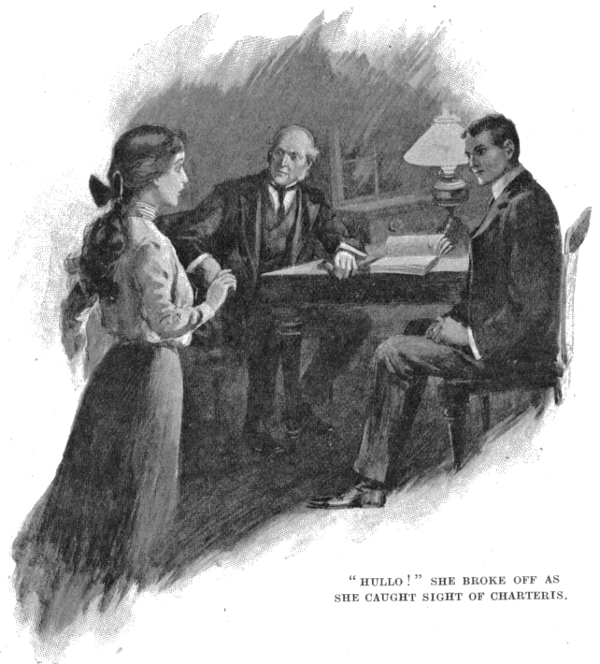

A few minutes later he presented himself at the Headmagisterial door. The sedate Parker, the Head’s butler, who always filled Charteris with a desire to dig him hard in the ribs just to see what would happen, ushered him to the study.

The Headmaster was reading by the light of a lamp when Charteris came in. He laid down his book, and motioned him to a seat. After which there was an awkward pause.

“I have just received,” began the Head at last, “a most unpleasant communication. Most unpleasant. From whom it comes I do not know. It is, in fact—er—anonymous. I am sorry that I ever read it.”

He paused. Charteris made no comment. He guessed what was coming. He, too, was sorry that the Head had ever read the letter.

“The writer says that he saw you, that he actually spoke to you at the athletic sports at Rutton, yesterday. I have called you in to tell me if that is true.”

He fastened an accusing eye on his companion.

“It is quite true, sir,” said Charteris, steadily.

“What,” said the Head, sharply, “you were at Rutton?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You were perfectly aware, I suppose, that you were breaking the school rules by going there, Charteris?”

“Yes, sir.”

There was another pause.

“This is very serious,” said the Headmaster. “I cannot overlook this. I——”

There was a slight scuffle of feet outside in the passage, and a noise as if somebody was groping for the handle. The door flew open vigorously, and a young lady entered. Charteris recognised her in an instant as his acquaintance of the previous afternoon.

“Uncle,” she said, “have you seen my book anywhere? Hullo!” she broke off as she caught sight of Charteris.

“Hullo,” said Charteris, affably, not to be outdone in the courtesies.

“Did you catch your train?”

“No. Missed it.”

“Hullo, what’s the matter with your cheek?”

“I got a kick on it.”

“Oh, does it hurt?”

“Not much, thanks.”

Here the Headmaster, feeling perhaps a little out of it, put in his oar.

“Dorothy, you must not come here now. I am busy. But how, may I ask, do you and Charteris come to be acquainted?”

“Why, he’s him,” said Dorothy lucidly.

The Head looked puzzled.

“Him, the man, you know.”

It is greatly to the credit of the Head’s intelligence that he grasped the meaning of these words. Long study of the classics had quickened his faculty of seeing sense in passages where there was none. The situation dawned upon him.

“Do you mean to tell me, Dorothy, that it was Charteris who came to your assistance yesterday?”

Dorothy nodded energetically. Charteris began to feel exactly like a side-show.

“He gave the men beans,” she said.

“Dorothy,” said her uncle, “run away to bed” (a suggestion which she treated with scorn, it wanting a clear two hours to her legal bedtime). “I must speak to your mother about your deplorable habit of using slang. Dear me, I must certainly speak to her.”

Dorothy retired in good order. The Head was silent for a few minutes after she had gone. Then he turned to Charteris again. “You must understand, Charteris, that I cannot allow myself to be influenced in any way by what I have just learned. I cannot overlook your offence. I have my duty as a headmaster to consider. You have committed a very serious breach of school rules, and I must punish you for it. You will, therefore, write me out—er—ten lines of Vergil by to-morrow evening, Charteris.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Latin and English,” continued the relentless pedagogue.

“Yes, sir.”

“And, Charteris—I am speaking now—er—unofficially: not as a headmaster, you understand—if in future you would cease to break school rules simply as a matter of principle—for that, I fancy, is what it amounts to—I—er—well, I think we should get on better together, Charteris. Which I think would be a very pleasant state of things. Good-night, Charteris.”

“Good-night, sir.”

The Head extended a hand. Charteris took it, and his departure. The Headmaster, opening his book again, turned over a new leaf.

So did Charteris.

The End.

Editor’s note:

Printer’s error corrected above:

In ch. V, magazine had “bit scratched, that’ all”; missing “s” inserted after apostrophe.

In ch. V, magazine had “waited for the dogcart—it sounded like a dog-cart—”; changed to “dog-cart” both times for consistency.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums