Chapter 19

The Fight behind the Gym

“HALF a second,” said one of the group, who had not spoken before, a smallish, wiry boy with a pleasant, cheerful face, which Jimmy liked at sight.

“What’s up now, Freddy?”

“Only this. It strikes me that it’s playing it a bit low down on this chap to hound him into a fight when he comes as an ambassador from another school.”

“My deah chap,” protested Patterne, “you surely don’t call that beastly hole a school?”

Jimmy glared, but, having one fight already on his hands, he refrained from anything in the shape of an active protest. Tommy’s cousin’s sneer was, however, too much for Ram, whose devotion to Marleigh was almost a religion.

“That,” he said warmly, “is the crying injustice and beastly shame. For why, Hon’ble Patterne, is our Alma Mater the hole and no school? Do we not sit at the feet of learned masters and drink in jolly stiff lessons? Do not our fathers pay heavily, and through the nose, for us to imbibe the Pierian stream of knowledge? I bite my thumb at you, young sir.” Here Ram suited the action to the word, to the uproarious delight of the bystanders. “I am not constitutionally a bellicose, or I would give you the slap in the ear, or the nose-punch. You are an insignificant chap not worth notice.”

“Oh, I am, am I! Well, look heah——”

The boy called Freddy—Frederick Bowdon, to give him his full name—interposed.

“Chuck it, Pat,” he said. “He’s perfectly right. It was a scuggish thing to say, and you ought to apologise. I don’t know what you fellows think, but I call it a beastly shame setting on a man from another school like this. He’s under a flag of truce. I say,” he added, turning to Jimmy, “you needn’t fight unless you want to, you know. If O’Connell is spoiling for a row, I’ll take him on.”

Jimmy could not help laughing at this bright suggestion.

“It’s awfully good of you,” he said, “but don’t worry about me. I’m all right.”

“If he funks it——” began O’Connell.

“I don’t,” said Jimmy, shortly. “Shall we be going on?”

There was a general movement towards the gymnasium, a grey stone building which lay at the far end of the school grounds. Bowdon came to Jimmy, and walked with him. Other groups of boys whom they met, having inquired what was happening, and learning that it was a fight, joined themselves to the throng, until it became quite a crowd. As they neared the gymnasium, there must have been almost a hundred intending spectators.

“I’m awfully sorry this has happened,” said Bowdon to Jimmy, as they walked along. “I call it a bally disgrace to the school. An ambassador ought to be safe from this sort of thing. The fact is, the school’s in a beastly rotten state just now. O’Connell and his gang seem to think they can do just what they like. I’m about the only fellow, as a matter of fact, who can take on O’Connell, and he keeps clear of me. I’m not saying it from side, you know. I beat him in the light-weight boxing last term. He’s a jolly tough nut to crack.”

Jimmy thought he might as well get a few hints as to what sort of fighter this was whom he was going to meet.

“What’s he like? I mean as a fighter. He looks strong.”

“He is,” said Bowdon, with conviction. “He’s as strong as a horse, and as hard as a block of wood. He hasn’t got very much science, luckily. I beat him on points in the boxing. If it had been to a finish, I don’t know what might have happened. He was pretty nearly as fresh when we left off, as when we started. If I were you, I should keep away from him as much as possible, and especially dodge his right. He’s got a tremendous right. I sha’n’t forget one smash in the ribs he got me in the second round, in a hurry. I thought I was out.”

This was not very comforting; but Jimmy had formed much the same opinion of his opponent from the mere sight of him. The red-haired one was evidently plentifully endowed with muscle. A clean hit from him was not likely to be a pleasant experience. Jimmy hoped that his own quickness, which was remarkable, would be sufficient to prevent this. If it did not, it could not be helped. He would fight his best, and he would fight as long as he could stand. If he could not win, he must be content with losing gamely.

“I wish you’d let me second you,” said Bowdon. “I might be able to give you some tips about him during the fight.”

“I should be awfully glad if you would,” said Jimmy gratefully. “It’s jolly good of you.”

“Not a bit. I hope you’ll knock him out. A jolly good licking would do him all the good in the world. Chaps here have begun to look on him as a little tin god.”

“But if you licked him——”

“Oh, they’ve forgotten that. You see, he bucks about, and behaves as if the place belonged to him, while I lie fairly low. I never interfere with anybody, if they leave me alone. He sides about like a bally swashbuckler. Here we are. Hullo, here’s Williamson, that’s good. We’ll get him to referee. Then we can be sure of having fair play. He’s captain of football here, and was runner-up in the heavy-weights at Aldershot last year. He won’t stand any rot from the O’Connell gang.”

A tall, powerful-looking boy had joined the group. He was in football clothes and a blazer. He had been playing fives in one of the courts near the gymnasium.

“Hullo,” he said, “what’s all this?”

A dozen voices started to explain.

“One at a time,” he said. “What’s on, Freddy?”

“It’s a fight, Williamson,” said Bowdon, “between a Marleigh chap—by the way, what’s your name?—a Marleigh chap named Stewart——”

“What’s a Marleigh chap doing here?”

“He came to see Patterne about the second eleven match.”

“Oh, yes. The second are playing Marleigh instead of the Emeriti. But, look here, this won’t do. If fellows from other schools come here, they mustn’t be lugged into fights.”

“That’s just what I said. But Stewart wants to fight.”

“Who’s it with?”

“O’Connell.”

“Oh.”

From his voice it seemed that O’Connell’s reputation as a swashbuckler was not unknown to the football captain. He looked with interest at Jimmy.

“Do you really want to fight?”

“Yes,” said Jimmy. “He hit me. I should like to try and hit him for a change.”

“Oh, all right, then.”

“I say, Williamson,” said Bowdon, “will you referee?”

“All right, if you want me to. Give us a watch, someone. Thanks. Two minute rounds, of course, and a half a minute in between. Till one of you has had enough. Who’s seconding you, Stewart?”

“I am,” said Bowdon.

“That’s all right, then. He’s lucky as far as that goes. Are you ready?”

Two basins of water and a couple of towels had appeared mysteriously from nowhere. Jimmy and his opponent got ready. A large ring had been formed. O’Connell stepped into it. Jimmy followed him. Two chairs had been brought. Jimmy and O’Connell sat in them, waiting for the call of time.

Chapter 20

The End of the Fight—and After

JIMMY sat in his corner looking at O’Connell on the opposite side of the ring, while Bowdon spoke to Williamson.

He knew he had taken on a big thing, but he had to go through with it; even if he had desired it, there could be no backing out now. It was not that he was afraid, but he felt his heart thumping against his ribs, and wondered if he looked pale or nervous—he hoped not—before that excited crowd, a crowd that was increasing every second. They were not his friends, that was the thought at the back of everything; though they were not actively hostile, they were not his friends, but O’Connell’s. To them it was Alderton against Marleigh, and it was their man who must win. Jimmy knew this, and the knowledge did not make him feel any better.

Then he saw Ram standing beside him, and smiled. Ram, looking very woe-begone and miserable, gazed vaguely round the ring through his big spectacles as if searching for some friendly face.

Then Bowdon crossed over, and Williamson turned to the crowd.

“You fellows must keep back, understand; and no shouting during the rounds. See. Now, all ready? Wait a bit,” and he looked at his watch. “Time.”

Jimmy’s heart gave an extra big thump, a cold shiver ran down his back, and he drew in a long breath, swallowing with difficulty; but as he advanced to meet O’Connell the nervousness, the dread of the unexpected, left him, and he felt strangely calm, ready for anything.

It was action; action now. No waiting any longer: here was something solid, flesh and blood against him, and, even if he was beaten, he was going to fight for it.

He held out his hand, but O’Connell took no notice, and led at his head quickly. Jimmy sidestepped almost mechanically, and as he did so, found himself saying in his own mind, “This chap is no gentleman; this is not playing the game,” then he ducked as O’Connell swung his right again.

The Alderton boy meant to finish things quickly, a long fight was not to his taste; his game was to rush, to hit hard and often, and to trust to his strength to pull him through. This Marleigh fellow must be shown that he could not hope to stand up against his betters, and he went at Jimmy, hitting viciously with both hands.

Jimmy gave back a couple of steps and stopped a hard smash at his body, then he countered. He had not realised he had done so, until he felt a sudden unlooked-for jar on the knuckles, and saw a trickle of blood on the other’s chin; but he had to give way again, and then his foot slipped on the grass and he went over.

The spectators, forgetting all instructions, yelled, and “Get back, O’Connell,” shouted Williamson, “get back,” and to the crowd, “shut it; that’s only a slip.”

Jimmy was up again at once, smash—smash—O’Connell grunted as he bored him to the side, and then, “Time.”

Ah! that delicious half-minute’s rest, lying back in his chair, breathing deeply; while Bowdon flapped him with a towel, and another boy, with a serious brown face and grey eyes, sponged him with refreshing water. Ram, silent till now, turned to the crowd surrounding him.

“This is the strenuous, Misters. This is no mere casus belli, but hot stuff.”

“Well done,” said Bowdon all in a breath, not waiting for an answer, “keep away from him, right away, out-fighting you know, make him sweat, did that tumble shake you up? You ought to be at school here, oughtn’t he, David? Mind his right, and—hullo!”

“Time,” and Jimmy stood up once more.

O’Connell had tried to rush things the first round, he tried even harder in the second, and was on Jimmy like lightning, hitting at him savagely, hustling him all round the ring.

Jimmy, on his side, knew that if once that terrible right got fairly home he was done for; so he kept away, with his left well up, dodging the other’s leads as best he could, waiting for the opening he prayed would come. But it was beginning to tell, this fierce sledgehammer work; O’Connell was far stronger than he was, and was showing it more and more every moment. Then O’Connell dropped his guard slightly, ever so slightly, but it was enough. Jimmy dived in and shook him up with a punch on the body, then in return he went over, rushed off his feet, and time was called.

But Jimmy went to his corner knowing that his man was no boxer, just a plain, straight-forward slogger. He could fight, yes; but box, no, not a bit.

The applause at the end of the round was now more evenly divided; Jimmy felt that he was making friends. Had he but known it, the Alderton boys were beginning to feel just a little ashamed of their truculent-looking champion, and the way he had forced this stranger into a fight. Until the two opponents had stood up to each other in their shirt-sleeves, nobody had realised how much slighter Jimmy was, and his plucky stand was making him popular. It had been a joke at first, this fight; now they shuffled uneasily as they watched the Marleigh boy taking his punishment without flinching; and after all, what was the fight about? And then, again—but all the same, Alderton must win.

Jimmy’s head was singing, his mouth was bleeding, and his arms felt a bit heavy, but he was still fresh, and breathed easily; while O’Connell opposite gasped and scowled at his seconds, as they bent over him.

And once more they stood up to fight.

O’Connell, his face marked with purple blotches, his eyes glittering nastily, again led. He knew that this fight he had so eagerly entered on was going to tax his full powers; here was this kid standing up to him still; but this would be the last round, and he rushed, but without the dash of the first two rounds.

Jimmy edged a blow off his body, and then ducked as O’Connell’s right whistled past his ear; he countered and felt the crash of his fist against the other’s body, and was in again with his right, good blows both, then he found himself struggling in O’Connell’s arms.

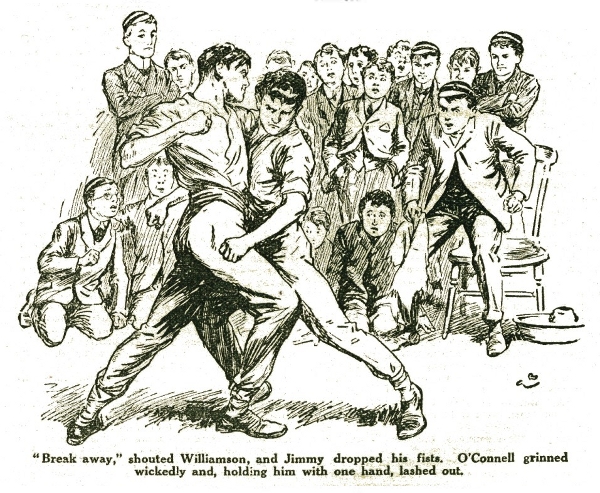

“Break away,” shouted Williamson, “break away.” O’Connell’s face was white, and he breathed heavily, those two punches were beginning to tell already. Then “break away, there,” and Jimmy dropped his fists. O’Connell grinned wickedly, and holding him with one hand, lashed out.

Whether it was a foul or not, was always a disputed point at Alderton, and if the truth be known, rather a sore subject for a long time. Williamson, who was on the wrong side to see, thought not; he hesitated to believe that an Alderton fellow could be guilty of hitting while he held an opponent. It is a thing that no one ever does, and there Williamson left it. And then—Jimmy was on his back, staring up at the sky, wondering; then he heard—“one”—Great Scott; he must get up, he mustn’t lie there—“two”—he heard Bowdon shouting at Williamson—“three”—he was on his hands and knees—“four”—on one knee—“five”—he was keeping his mind firmly fixed on the fact that he must stand up, if it killed him—“six”—and “get back, O’Connell.” Someone said “seven” —he was up at last, and O’Connell, white faced and hideous, with his mouth open, was on him.

Jimmy had been badly shaken, but the blow had not got him fairly, or he would not have been on his feet as he was; still he knew that it would try him hard to get through the rest of the round. What had he to remember? Oh! yes, that right—and he fought on in a whirl. Why did not the other finish him off? He was not hitting very hard; was he staying his hand? And then in a flash came the thought, he couldn’t, he couldn’t; he was done too, and Jimmy suddenly felt better. “Time.”

As he turned, a storm of cheers broke out, and Jimmy tottered to his corner, feeling that even if he was an alien, an outlander, somehow he, Jimmy Stewart of Marleigh School, was being cheered by a throng of Alderton fellows, and again he felt better.

Bowdon was flapping him with the towel, sending a perfect current of air into his lungs. That was better—a-ah!—much better, and he breathed deeply. When one is in perfect training as Jimmy was, one can stand a lot of knocking about, and Jimmy felt that that blow of O’Connell’s was a mere accident. Whether it was fair or not never troubled him. It would not happen again, he told himself, and his head was better already; after all it was only the sudden shock.

“That,” said a voice, his solemn-faced second’s, “was the most caddish thing I have ever come across. If he had got you fair on——”

“Yes, Williamson was on the off side, but that chap held you as he hit, I swear he did. It’s a shame, he ought to have been disqualified. But you hurt him, I think, more than he did you, all the same.”

“Are you feeling all right?”

“Yes, thank you,” said Jimmy, “my neck’s a bit stiff. Otherwise I’m quite fit.”

“Good man.”

“Time!”

O’Connell moved stiffly and with an effort. Jimmy’s two body blows in the last round were hurting him.

They circled round each other quietly. O’Connell led at Jimmy’s head, but was short, and Jimmy jumped in. O’Connell staggered. Again they moved round, and this time Jimmy led, and O’Connell in his turn got home. But his blows lacked strength. And then Jimmy, from the corner of his eye, saw Bowdon wave his hand. He jumped in again. O’Connell gave way. Jimmy made his big effort. With all the strength that was left in him he went in left and right.

Then suddenly there was nothing to hit at. In a sort of dream he saw that O’Connell was lying on the ground. He stepped back, while Williamson counted the seconds in a solemn voice. O’Connell paid no attention. He was evidently finished. “Ten,” said Williamson.

Jimmy felt himself gripped by the hand, the centre of a crowd of excited faces. He had beaten their man, but that did not matter. They were sportsmen at Alderton, and they meant to make up for the way in which they had treated this stranger from another school. Everybody was cheering, and slapping Jimmy’s back.

“Well played,” said a quiet voice. “That was ripping.” Jimmy turned and saw Bowdon.

“Thanks awfully for seconding me,” he said.

“Not a bit,” said Bowdon. “Come and have some tea.”

They made much of Jimmy and Ram in Bowdon’s study. Ram was in his element. He made speeches. He drank Jimmy’s health in tea. He drank eternal friendship to Bowdon and the others. As a wind-up, by special request, he recited “The Charge of the Light Brigade.”

“There are the stout fellows and good chaps,” he said enthusiastically to Jimmy, as they started to ride home, turning and waving a hand benevolently to the cheering group at the big gate. “We came in like lamb, and have gone out like lion and big pot. Huzza! You are the courageous, Hon’ble Stewart.”

Jimmy was feeling too tired for conversation. His head was aching from his exertions. He rode on in silence.

Half-way home he felt a sudden jarring and bumping.

“Dash it, I’ve punctured,” he said.

He got off.

“You ride on, Ram,” he said. “I’ll stop and patch up this beastly tyre.”

“Shall I not stand by friend in distress?” asked Ram.

“No, thanks. I’d rather be alone. I’m feeling a bit done. I don’t want to talk much.”

Ram rode off. Jimmy got out his repairing outfit, and was preparing to take the tyre off, when a spot of rain fell on him, then another. In another moment it was coming down in earnest. Jimmy looked about him for shelter.

A hundred yards away, separated from the road by a field, was a deserted, tumble-down cottage. It was not an inviting-looking spot, but, at any rate, it had a roof. It would at least be drier in there than out on the road. He made a dash for it, wheeling his machine.

“Inside and under shelter,” he chuckled.

“Old Ram’ll get soaked,” he said, dabbing at his clothes with his handkerchief. “Rum old place, this. Shouldn’t care to live here, but it’s all right to keep out the rain. Hullo! what’s that?”

Somebody was coming towards the cottage. At first he thought it might be Ram, returning for shelter. But a voice made itself heard, a man’s voice. Jimmy could not distinguish the words, but with a sudden start he recognised the voice. There was no mistaking those deep tones. It was Marshall who was approaching.

(To be continued next week.)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums