Note: Thanks to Neil Midkiff for providing the transcription and images for this story. See his comments at the end of the story as well.

Cosmopolitan, February 1910

NY

man under thirty years of age who tells you he is not afraid

of an English butler lies. Carpers may cavil at this statement. Possibly

cavilers may carp. I seem to hear them at it. All around me, I repeat,

I seem to hear the angry murmur of carpers caviling and cavilers carping.

Nevertheless, it is true. He may not show his fear. Outwardly he may be

brave, aggressive even, perhaps to the extent of calling the great man

“Say!” But in his heart, when he meets that cold, blue, introspective

eye, he quakes.

NY

man under thirty years of age who tells you he is not afraid

of an English butler lies. Carpers may cavil at this statement. Possibly

cavilers may carp. I seem to hear them at it. All around me, I repeat,

I seem to hear the angry murmur of carpers caviling and cavilers carping.

Nevertheless, it is true. He may not show his fear. Outwardly he may be

brave, aggressive even, perhaps to the extent of calling the great man

“Say!” But in his heart, when he meets that cold, blue, introspective

eye, he quakes.

The effect that Keggs, the butler at the Keiths’, had on Marvin Rossiter was to make him feel as if he had been caught laughing in a cathedral. He fought against the feeling. He asked himself who Keggs was, anyway; and replied defiantly that Keggs was a menial, and an overfed menial. But all the while he knew that logic was useless.

When the Keiths invited him to their country house he had been delighted. They were among his oldest friends. He liked Mr. Keith. He liked Mrs. Keith. He loved Elsa Keith, and had from boyhood up. If ever there was a visit that had promised well, this visit was that visit.

But things had gone wrong. As he leaned out of his bedroom window, at the end of the first week, preparatory to dressing for dinner, he was more than half inclined to make some excuse and get right out of the place next day. The house was full of English servants. The footmen he could have endured, but the bland dignity of Keggs had taken all the heart out of him. Marvin was accustomed to think himself as good as the next man, but under Keggs’s eye his self-respect left him and his back-bone became a mere streak of jelly. But it was not Keggs alone who had driven his thoughts toward flight. Keggs was merely a passive evil, like toothache or a rainy day. What had begun actively to make the place impossible was a perfectly pestilential young man of the name of Barstowe.

The house-party at the Keiths’ had originally been, from Marvin’s point of view, almost ideal. The rest of the men were of the speechless, mustache-tugging breed. They had come to shoot, and they shot. They did no wooing on the side. When they were not shooting they congregated in the billiard-room and devoted their powerful intellects exclusively to snooker-pool, leaving Marvin free to talk undisturbed to Elsa. He had been doing this for five days, with great contentment, when Aubrey Barstowe arrived. Mrs. Keith had of late developed leanings toward culture. In her town house on a Thursday afternoon a charge of small shot, fired in any direction, could not have failed to bring down a poet, a novelist, or a painter. Aubrey Barstowe, author of “The Soul’s Eclipse” and other poems, was a constant member of the Thursday bread-line. A youth of insinuating manners, he had appealed to Mrs. Keith from the start, and unfortunately the virus had extended to Elsa. Many a pleasant, sunshiny Thursday afternoon had been poisoned for Marvin by the sight of Aubrey and Elsa together on a distant settee, matching temperaments. And here he was again, just as things were beginning to go well, as large as life and twice as temperamental.

The rest is too painful. It was a rout. The poet did not shoot, so that, when Marvin returned of an evening, his rival was about five hours of soul-to-soul talk up and only two to play. And those two, the after-dinner hours, which had once been the hours for which Marvin had lived, were pure torture. When it’s a choice between playing snooker-pool and being treated as a piece of furniture by the girl you love, what’s the use?

So engrossed was he with his thoughts that the first intimation he had that he was not alone in the room was a genteel cough. Behind him, holding a small can, was Keggs.

“Your ’ot water, sir,” said the butler austerely, but not unkindly.

Keggs was a man—one must use that word, though it seems grossly inadequate—of medium height, pigeontoed at the base, bulgy halfway up, and bald at the apex. He had a restrained dignity, and his voice was soft and grave. But it was his eye that quelled Marvin—that cold, blue, dukes-have-treated-me-as-an-elder-brother eye.

He fixed it upon Marvin now, as he added, placing the can on the floor, “It is Frederick’s duty, but to-night I hundertook it.”

Marvin had no answer. He was dazed. Keggs had spoken with the proud humility of an emperor compelled by misfortune to shine shoes.

“Might I ’ave a word with you, sir?”

“Ye-e-ss,” stammered Marvin. “Won’t you take a—I mean, yes, certainly.”

“It is perhaps a liberty——” began Keggs. He paused, and raked Marvin with the eye that had rested on dining dukes.

“Not at all,” said Marvin hurriedly.

“I should like,” went on Keggs, bowing, “to speak to you on a somewhat hintimate subject—Miss Elsa.”

Marvin’s eyes and mouth opened slowly.

“You are going the wrong way to work, if you will allow me to say so, sir.”

Marvin’s jaw dropped another inch. “Wha-a-?”

“Women, sir,” proceeded Keggs “—young ladies—are peculiar. I ’ave ’ad, if I may say so, certain hopportunities of observing their ways. Miss Elsa reminds me in some respects of Lady Angelica Fendall, whom I ’ad the honor of knowing when I was butler to ’er father, Lord Stockleigh. ’Er ladyship was hinclined to be romantic. She was fond of poetry, like Miss Elsa. She would sit by the hour, sir, listening to young Mr. Knox reading Tennyson, which was no part of ’is duties, ’e being employed by ’is lordship to teach Lord Bertie Latin and Greek and what not. You may ’ave noticed, sir, that young ladies is often took by Tennyson, hespecially in the summer time. Mr. Barstowe was reading Tennyson to Miss Elsa in the ’all when I passed through just now; ‘The Princess,’ if I’m not mistaken.”

“I don’t know what the thing was,” groaned Marvin. “It made a hit with her.”

“Lady Angelica was greatly haddicted to ‘The Princess.’ Young Mr. Knox was reading portions of that poem to ’er when ’is lordship come upon them. Most rashly ’is lordship made a public hexposé and packed Mr. Knox off next day. It was not my place to volunteer hadvice, but I could ’ave told ’im what would ’appen. Two days later ’er ladyship slips away to London early in the morning, and they’re married at a registry office. That is why I say that you are going the wrong way to work with Miss Elsa, sir. With certain types of ’igh-spirited young ladies hopposition is useless. Now when Mr. Barstowe was reading to Miss Elsa on the hoccasion to which I ’ave halluded, you were sitting by, trying to engage her hattention. It’s not the way, sir. You should leave them alone together. Let ’er see so much of ’im, and nobody else but ’im, that she will grow tired of ’im. Fondness for poetry, sir, is very much like the whiskey ’abit. You can’t cure a man what ’as got that by hopposition. When I was butler to Lord Emsworth, sir, ’is heir, the Honorable Claude Havant, most unfortunately became haddicted to the ’abit. The doctors didn’t stop ’is whiskey. They orders ’im more. ’E ’ad it in ’is tea of a morning, and in ’is shaving-mug, sir, and ’e took ’is bath in whiskey and water, and there was whiskey in ’is deviled kidney at breakfast, and on ’is pocket-’andkerchiefs, and everywhere, sir. And about a month later there was a ’orrible scandal at the Bachelors’ Club through Mr. John pretty near killing a waiter; it transpired that the hinjured man had brought Mr. John a whiskey and soda hinstead of the barley-water what ’e ’ad ordered. Now, if you will permit me to offer a word of hadvice, sir, I say let Miss Elsa ’ave all the poetry she wants. Don’t let her ’ave no rest.”

Marvin was conscious of but one coherent feeling at the conclusion of this address, and that was one of amazed gratitude. A lesser man who had entered his room and begun to discuss his private affairs would have had reason to retire with some speed; but that Keggs should descend from his pedestal and interest himself in such lowly matters was a different thing altogether.

“I’m very much obliged——” he was stammering, when the butler raised a deprecatory hand.

“My interest in the matter,” he said smoothly, “is not entirely haltruistic. For some years back, in fact since Miss Elsa was a débutante, we ’ave ’ad a matrimonial sweepstakes in the servants’ ’all at each ’ouse-party. The names of the gentlemen in the party are placed in an ’at and drawn in due course. Should Miss Elsa become engaged to any member of the party, the pool goes to the drawer of ’is name. Should no engagement hoccur the money remains in my charge until the following year, when it is hadded to the new pool. Of course, Miss Elsa might haccept some gentleman in town, whose name is not on the list of starters. In that case the money would be returned to the depositors. It is merely a little sporting flutter to relieve the hintense monotony of country life. ’Itherto I ’ave ’ad the misfortune to draw nothing but married gentlemen, but on this hoccasion I ’ave secured you, sir. And I may tell you, sir,” he added with stately courtesy, “that in the hopinion of the servants’ ’all your chances are ’ighly fancied, very ’ighly. The pool ’as now reached considerable proportions, and, ’aving ’ad certain losses on the turf very recent, I am hextremely anxious to win it. So I thought, if I might take the liberty, sir, I would place my knowledge of the sex at your disposal. You will find it sound in hevery respect. That is all. Thank you, sir.”

Marvin’s feelings had undergone a complete revulsion. In the last few minutes the butler had shed his wings and grown horns, cloven feet, and a forked tail. His rage deprived him of words. He could only gurgle.

“Don’t thank me, sir,” said the butler indulgently. “I ask no thanks. We are working together for a common hobject, and any little ’elp I can provide is given freely.”

“You old scoundrel!” shouted Marvin, his wrath prevailing even against that blue eye. “You have the gall to come to me and——” He stopped. The thought of these hounds, these demons, coolly gossiping and speculating below stairs about Elsa, making her the subject of “little sporting flutters to relieve the monotony of country life,” choked him.

“I shall tell Mr. Keith,” he said.

The butler shook his bald head gravely. “I shouldn’t, sir. It is a ’ighly fantastic story, and I don’t think he would believe it.”

“Then I’ll—oh, get out!” He dropped into a chair and wiped his forehead.

Keggs bowed deferentially. “If you wish it, sir,” he said, “I will withdraw. If I may make the suggestion, sir, I think you should commence to dress. Dinner will be served in a few minutes. Thank you, sir.”

He passed softly out of the room.

It was more as a demonstration of defiance against Keggs than because he really hoped that anything would come of it that Marvin approached Elsa next morning after breakfast. Elsa was strolling with the bard on the terrace in front of the house, but Marvin broke in on the conference with the dogged determination of a wedge of footballers.

“Coming out with the guns to-day, Elsa?” he said.

She raised her eyes. There was an absent look in them.

“The guns?” she said. “Oh, no. I hate watching men shoot.”

She raised her eyes. There was an absent look in them.

“The guns?” she said. “Oh, no. I hate watching men shoot.”

“You used to like it.”

“I used to like dolls,” she said impatiently.

Mr. Barstowe gave tongue. He was a slim, tall, sickeningly beautiful young man, with large dark eyes full of expression. “We develop,” he said. “The years go by and we develop. Our souls expand—timidly, at first, like little, half-fledged birds, stealing out from the——”

“I don’t know that I’m so set on shooting to-day, myself,” said Marvin. “Will you come round the links?”

“I’m going out in the automobile with Mr. Barstowe,” said Elsa.

“The automobile!” cried Mr. Barstowe. “Ah, Marvin, that is the very poetry of motion. I never ride in an automobile without those words of Shakespeare’s ringing in my mind, ‘I’ll put a girdle round about the earth in forty minutes.’ ”

“I shouldn’t give way to that sort of thing if I were you,” said Marvin. “The police are pretty sore on joy-riding in these parts.”

“Mr. Barstowe was speaking figuratively,” said Elsa, with disdain.

“Was he?” grunted Marvin, whose sorrows were tending to make him every day more like a sulky schoolboy. “I’m afraid I haven’t the poetic soul.”

“I’m afraid you haven’t,” said Elsa.

There was a brief silence. A bird made itself heard in a neighboring tree.

“ ‘The moan of doves in immemorial elms,’ ” quoted Mr. Barstowe softly.

“Only it happens to be a rain-crow in a sycamore,” said Marvin, as the bird flew out.

Elsa’s chin tilted itself in scorn. Marvin turned on his heel and walked back to the house.

“It’s the wrong way, sir, it’s the wrong way,” said a voice. “I was hobserving you from a window, sir. It’s Lady Angelica over again. Hopposition is useless, believe me, sir.”

Marvin faced round, flushed and wrathful. The butler went on, unmoved.

“Miss Elsa is going for a ride in the hautomobile to-day, sir.”

“I know that.”

“Uncommonly tricky things, these hautomobiles. I was saying so to Roberts, the chauffeur, just as soon as I ’eard Miss Elsa was going out with Mr. Barstowe. I said: ‘Roberts, these hautomobiles is tricky. Break down when you’re twenty miles from hanywhere as soon as look at you. Roberts,’ I said, slipping him a ten-dollar bill, ‘ ’ow awful it would be if the car should break down twenty miles from hanywhere to-day!’ ”

Marvin stared. “You bribed Roberts to——”

“Sir! I gave Roberts the ten dollars because I’m sorry for him. He is a poor man, and ’as a wife and family to support.”

“Very well,” said Marvin sternly, “I shall go and warn Miss Keith.”

“Warn ’er, sir!”

“I shall tell her that you have bribed Roberts to make the car break down so that——”

Keggs shook his head. “I fear she would ’ardly credit the statement, sir. She might even think that you were trying to keep ’er from going for your own personal ends. Young ladies,” continued Keggs, with sorrow, “are frequently like that. They mean no ’arm, but they are prone to place herroneous constructions on haltruistic hacts. I should let well alone, sir, I reelly should.”

“I believe you’re the devil,” said Marvin.

“I ’ope you will come to look on me, sir,” said Keggs unctuously, “as your good hangel.”

Marvin shot abominably that day, and, coming home in the evening gloomy and savage, went straight to his room and did not reappear till dinner-time. Elsa had been taken in by one of the mustache-tuggers. Marvin found himself seated at her other side. It was so pleasant to be near her and to feel that the bard was away at the other end of the table that, for the moment, his spirits revived. There had been a certain amount of coldness, it was true, about their parting that morning, but he would make that all right. He would be bright and cheery. He would show by his manner that all was forgotten and forgiven.

“Well, how did you like the joy-ride?” he asked with a smile. “Did you put that girdle round the world?”

She looked at him—once. The next moment he had an uninterrupted view of her shoulder, and heard the sound of her voice as she prattled gaily to the man on her other side. His heart gave a sudden bound. He understood now. That demon butler had had his wicked way. Good heavens, she had thought he was taunting her! He must explain at once. He—

“Hock or sherry, sir?”

He looked up into Keggs’s expressionless eyes. The butler was wearing his on-duty mask. There was no sign of triumph in his face.

“What?” said Marvin dizzily.

“Hock or sherry, sir?”

“Oh, sherry. I mean hock. No, sherry. Neither.”

This was awful. He must put it right.

“Elsa,” he said.

She was engrossed in her conversation with her neighbor.

From down the table, in a sudden lull in the talk, came the voice of Mr. Barstowe. He seemed to be in the middle of a narrative. “Fortunately,” he was saying, “I had with me a volume of Shelley and one of my own little efforts. I had read Miss Keith the whole of the latter and much of the former before the chauffeur announced that it was once more possible——”

“Elsa,” said the wretched man, “I had no idea— You don’t think——”

She turned to him. “I beg your pardon?” she said very sweetly.

“I swear I didn’t know— I mean, I’d forgotten— I mean——”

She wrinkled her forehead. “I’m really afraid I don’t understand.”

“I mean, about the automobile breaking down.”

“The automobile? Oh, yes. Yes, it broke down. We were delayed quite a little while. Mr. Barstowe read me some of his poems. It was perfectly lovely. I was quite sorry when Roberts told us we could go on again. But do you really mean to tell me, Mr. Lambert, that you——” And once more the world became all shoulder.

When the men trailed into the presence of the ladies for that brief séance on which etiquette insisted before permitting the stampede to the billiard-room, Elsa was not to be seen.

“Elsa?” said Mrs. Keith, in answer to Marvin’s question. “She has gone to bed. The poor child has a headache. I’m afraid she had a tiring day.”

There was an early start for the guns next morning, and, as Elsa did not appear at breakfast, Marvin had to leave without seeing her. His shooting was even worse than it had been on the previous day.

It was not till late in the evening that the party returned to the house. Marvin, on his way to his room, met Mrs. Keith on the stairs. She appeared somewhat agitated.

“Oh, Marvin,” she said, “I’m so glad you’re back. Have you seen anything of Elsa?”

“Elsa?”

“Wasn’t she with the guns?”

“With the guns?” said Marvin, puzzled. “No.”

“I have seen nothing of her all day. I’m getting worried. I can’t think what can have happened to her. Are you sure she wasn’t with the guns?”

“Absolutely certain. Didn’t she come in to lunch?”

“No. Tom,” she said, as Mr. Keith came up, “I’m so worried about Elsa. I haven’t seen her all day. I thought she must be out with the guns.”

Mr. Keith was a man who had built up a large fortune in Wall Street mainly by consistently refusing to allow anything to agitate him. He carried this policy into private life. “Wasn’t she in at lunch?” he asked placidly.

“I tell you I haven’t seen her all day. She breakfasted in her room.”

“Late?”

“Yes. She was tired, poor girl.”

“If she breakfasted late,” said Mr. Keith, “she wouldn’t need any lunch. She’s gone for a stroll somewhere, and forgotten the time.”

“Would you put back dinner, do you think?” inquired Mrs. Keith anxiously.

“I am not good at riddles,” said Mr. Keith comfortably, “but I can answer that one. I would not put back dinner. I would not put back dinner for the president. We can find a better use for it than that, eh, Marvin?”

“I think you’re heartless,” said Mrs. Keith.

“If I have no heart, that leaves all the greater vacuum to be filled. If Elsa doesn’t come back for dinner she’s no daughter of mine.”

Elsa did not come back for dinner. Nor was hers the only vacant place. Mr. Barstowe had also vanished. Even Mr. Keith’s calm was momentarily ruffled by this discovery. The poet was not a favorite of his, and it was only reluctantly that he had consented to his being invited at all; and, the presumption being that when two members of a house-party disappear simultaneously they are likely to be spending the time in each other’s company, he was annoyed. Elsa was not the girl to make a fool of herself, of course, but— He was unwontedly silent at dinner.

Mrs. Keith’s anxiety displayed itself differently. She was frankly worried, and mentioned it. By the time the fish had been reached, conversation at the table had fixed itself definitely on the one topic.

“It isn’t the automobile this time, at any rate,” said Mr. Keith. “It hasn’t been out to-day.”

One of the mustache-tuggers got the first inspiration he had had in thirty-seven years. “They couldn’t have gone far without it,” he said brilliantly, and subsided once more into obscurity.

“Why, that’s true,” said Mr. Keith. “I never thought of that.”

“It suddenly came to me,” said the inspired one, modestly crumbling bread.

“Why, they must be somewhere quite near.”

“They might have gone for a long walk,” suggested another of the mustache-tuggers, anxious to break into the gray-matter class in the other’s wake. His claims to inclusion were rejected by the experts.

“Barstowe couldn’t do a long walk,” said Mr. Keith, shaking his head.

The upstart accepted his exposure meekly, and made no further attempt to soar.

“I can’t understand it,” said Mrs. Keith for the twentieth time. And that was the farthest point reached in the investigation of the mystery.

By the time dinner was over, a spirit of unrest was abroad. The company sat about in uneasy groups. Snooker-pool was, if not forgotten, at any rate shelved. Somebody suggested search-parties, and one or two mustache-pullers wandered rather aimlessly out into the darkness.

Marvin was standing in the porch with Mr. Keith when Keggs approached. As his eyes lit on the butler Marvin was conscious of a sudden solidifying of the vague suspicion which had been forming in his mind. And yet that suspicion seemed so wild. How could Keggs, with the worst intentions, have had anything to do with this? He could not forcibly have abducted the missing pair and kept them under lock and key. He could not have stunned them and left them in a ditch. Nevertheless, looking at him standing there in his attitude of deferential dignity, with the light from the open door shining on his bald head, Marvin felt perfectly certain that he had in some mysterious fashion engineered the whole thing.

“Might I ’ave a word, sir, if you are at leisure?”

“Well, Keggs?” responded Mr. Keith.

“Miss Elsa, sir?”

“Yes?”

Keggs’s voice took on a sympathetic softness. “It was not my place, sir, to make any remark while in the dining-room, but I could not ’elp but hover’ear the conversation. I gathered from remarks that was passed that you was somewhat at a loss to account for Miss Elsa’s nonhappearance to-night, sir.”

Mr. Keith laughed shortly. “You gathered that, eh? Sherlock Holmes has nothing on you at the deduction business.”

Keggs bowed. “I think, sir, that possibly I may be hable to throw light on the matter.”

“What!” cried Mr. Keith. “Great Scott, man, then why didn’t you say so at the time? Where is she?”

“It was not my place, sir, to henter into the conversation of the dinner-table,” said the butler, with a touch of reproof. “If I might speak now, sir?”

Mr. Keith clutched at his forehead. “Heavens above! Do you want a signed permit to tell me where my daughter is? Get on, man, get on!”

“I think it ’ighly possible, sir, that Miss Elsa and Mr. Barstowe may be on the hisland in the lake, sir.”

About half a mile from the house was a picturesque strip of water, fifteen hundred yards in length and a little less in width, in the center of which stood a small and densely wooded island. It was a favorite haunt of visitors at the house when there was nothing else to engage their attention, but during the past week, with shooting to fill up the days, it had been neglected.

“On the island?” said Mr. Keith. “What put that idea into your head?”

“I ’appened to be rowing on the lake this morning, sir,” replied Keggs simply.

“Rowing on the lake!” Mr. Keith could hardly have displayed more surprise if the butler had said he had been turning somersaults.

“I frequently row of a morning, sir, when there are no duties to detain me in the ’ouse. I find the’ hexercise hadmirable for the ’ealth. I walk briskly to the boat-’ouse, and——”

“Yes, yes. I don’t want a schedule of your daily exercises. Cut out the reminiscences of the training-camp and come to the point.”

“As I was rowing on the lake this morning, sir, I ’appened to see a boat ’itched up to a tree on the hisland. I think that possibly Miss Elsa and Mr. Barstowe might ’ave taken a row out there. Mr. Barstowe would wish to see the hisland, sir—bein’ romantic.”

“But you say you saw the boat there this morning?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, it doesn’t take all day to explore a picayune island. What’s kept them all this time?”

“It is possible, sir, that the rope might not ’ave ’eld. Mr. Barstowe, if I might say so, sir, is one of these himpetuous literary pussons, and possibly ’e homitted to see that the knot was hadequately tied. Or,” his eyes, grave and inscrutable, rested for a moment on Marvin’s, “some party might ’ave come along and huntied it a-puppus.”

“Untied it on purpose?” said Mr. Keith. “What on earth for?”

Keggs shook his head deprecatingly, as one who, realizing his limitations, declines to attempt to probe the hidden sources of human actions. “I thought it right, sir, to let you know,” he said.

“Right? I should say so. If Elsa has been kept starving all day on that island by that long-haired— Here, come along, Marvin.” Mr. Keith turned and dashed off excitedly into the night.

Marvin remained for a moment, gazing fixedly at the butler.

“I ’ope, sir,” said Keggs cordially, “that my hinformation will prove of genuine hassistance to you.”

“Do you know what I would like to do to you?” said Marvin slowly.

“I think I ’ear Mr. Keith calling you, sir.”

“I would like to take you by the scruff of your neck, and——”

“There, sir! Didn’t you ’ear ’im then? Quite distinct it was.”

Marvin gave up the struggle with a sense of blank futility. What could you do with a man like this? It was like quarreling with Niagara Falls.

“I should ’urry, sir,” suggested Keggs respectfully. “ ‘I think Mr. Keith must ’ave met with some haccident. ’E will be needing you.”

His surmise proved correct. When Marvin came up, he found his host seated on the ground in evident pain.

“Twisted my ankle in a hole,” Mr. Keith explained briefly. “Give me an arm to the house, there’s a good fellow, and then run on down to the lake, and see if what that pompous ass said is true.”

Marvin did as requested—as far, that is to say, as the first half of the commission was concerned. As regarded the second, he took it upon himself to make certain changes. Having seen Mr. Keith to his room, he put the fitting-out of the relief-ship into the hands of a group of his fellow guests. Elsa’s feeling toward her rescuer might be one of unmixed gratitude. But it might, on the other hand, be one of resentment. He did not wish her to connect him in her mind with the episode in any way whatsoever. Marvin had once released a dog from a trap, and the dog had bitten him. He had been on an errand of mercy, but the dog had connected him with his sufferings, and acted accordingly. It occurred to Marvin that Elsa’s frame of mind would be uncommonly like that dog’s.

The rescue-party set off. Marvin lit a cigarette, and waited in the porch. It seemed a very long time before anything happened, but at last, as he was lighting his fifth cigarette, there came from the darkness the sound of voices. They drew nearer. Some one shouted:

“It’s all right. We’ve found them.”

Marvin threw away his cigarette and went indoors.

Elsa Keith sat up as her mother came into the room. Two nights and a day had passed since she had taken to her bed.

“How are you feeling to-day, dear?”

“Has he gone, mother?”

“Who?”

“Mr. Barstowe.”

“Yes, dear. He left this morning. He said he had business in New York.”

“Then I can get up,” said Elsa thankfully.

“I think you’re a little hard on poor Mr. Barstowe, Elsa. It was just an accident, you know. It was not his fault that the boat slipped away.”

“It was, it was, it was!” cried Elsa, thumping the pillow malignantly. “I believe he did it on purpose, so that he could read me his horrid poetry without my having a chance to escape. I believe that’s the only way he can get people to listen to it.”

“But you used to like it, darling. You said he had such a musical voice.”

“Musical

voice!” The pillow became a shapeless heap. “Mother, it was

like a nightmare! If I had seen him again, I should have had hysterics.

It was awful. If he had been even the least bit upset himself I

think I could have borne up. But he enjoyed it! He reveled

in it! He said it was like Omar Khayyam in the wilderness and Shelley’s

‘Epipsychidion’—whatever that is—and he prattled

on and on and read and read and read till my head began to split. Mother”—her

voice sank to a whisper—“I hit him!”

“Musical

voice!” The pillow became a shapeless heap. “Mother, it was

like a nightmare! If I had seen him again, I should have had hysterics.

It was awful. If he had been even the least bit upset himself I

think I could have borne up. But he enjoyed it! He reveled

in it! He said it was like Omar Khayyam in the wilderness and Shelley’s

‘Epipsychidion’—whatever that is—and he prattled

on and on and read and read and read till my head began to split. Mother”—her

voice sank to a whisper—“I hit him!”

“Elsa!”

“I did!” she went on defiantly. “I hit him as hard as I could, and he—he”—she broke off into a little gurgle of laughter—“he tripped over a bush, and fell right down. And I wasn’t a bit ashamed. I didn’t think it unladylike, or anything. I was just as proud as I could be. And it stopped him talking!”

“But, Elsa dear! Why?”

“The sun had just gone down, and it was a lovely sunset, and the sky looked like a great beautiful slice of rare beef, and I said so to him, and he said—sniffily—that he was afraid he didn’t see the resemblance. And I asked him if he wasn’t starving. And he said no, because as a rule all that he needed was a little ripe fruit. And that was when I hit him.”

“Elsa!”

“Oh, I know it was awfully wrong, but I just had to. And now I’ll get up. It looks lovely out.”

Marvin had not gone out with the guns that day. Mrs. Keith had assured him that there was nothing wrong with Elsa, that she was only tired; but he was anxious, and remained at home where bulletins could reach him. As he was returning from a stroll in the grounds he heard his name called, and saw Elsa lying in the hammock under the trees near the terrace.

“Why, Marvin, why aren’t you out with the guns?” she said.

“I wanted to be on the spot so that I could hear how you were.”

“How nice of you! Why don’t you sit down?”

“May I?”

Elsa fluttered the pages of her magazine. “You know, you’re a very restful person, Marvin. You’re so big and outdoory. How would you like to read to me for a while? I feel so lazy.”

Marvin took the magazine. “What shall I read? Here’s a poem by——”

Elsa shuddered. “Oh, please, no!” she cried. “I couldn’t bear it. I’ll tell you what I should love—the advertisements. There’s one about baked beans. I started it, and it seemed splendid. It’s at the back somewhere.”

“Is this it—Langley and Fielding’s Baked Beans?”

“That’s it.”

Marvin began to read. “ ‘Our beans are the best. We buy Michigan beans because they are the best. The choicest part of the crop is picked by hand, to give us only the whitest, the plumpest, the fullest grown. One must bake beans as we bake them, else they are not mealy, not digestible. They must be baked in live steam, else the top beans scorch before the others are even half baked.’ ”

Elsa was sitting with eyes closed and a soft smile of pleasure curving her mouth.

“Go on,” she said dreamily.

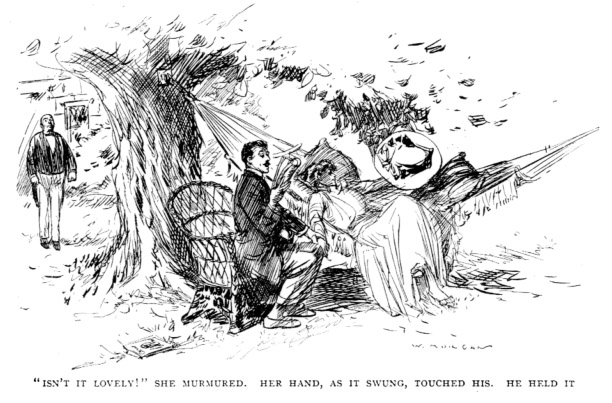

“ ‘Beans,’ ” resumed Marvin, with an added touch of eloquence as the theme began to develop, “ ‘must be baked without breaking, else they are not nutty. They must be baked with tomato sauce. Our tomatoes are ripened on the vines. The juce fairly sparkles. That is why Langley and Fielding’s Baked Beans have that superlative zest, that flavor, that blend.’ ”

“Isn’t it lovely!” she murmured. Her hand, as it swung, touched his. He held it. She opened her eyes. “Don’t stop reading,” she said. “I never heard anything so soothing.”

“Elsa!”

He bent toward her. She smiled at him. Her eyes were dancing.

“Elsa, I——”

“Mr. Keith,” said a quiet voice, “desired me to say——”

Marvin started away. He glared up furiously. Gazing down upon them stood Keggs. The butler’s face was shining with a gentle benevolence.

“Mr. Keith desired me to say that ’e would be glad if Miss Elsa would come and sit with ’im for a while.”

“I’ll come at once,” said Elsa, stepping from the hammock.

The butler bowed respectfully and turned away. They stood watching him as he moved across the terrace.

“What a saintly old man Keggs looks,” said Elsa. “Don’t you think so? He looks as if he had never even thought of doing anything he shouldn’t. I wonder if he ever has?”

“I wonder!” said Marvin.

“He looks like a stout angel. What were you saying, Marvin, when he came up?”

———————

Neil Midkiff comments:

While the Strand magazine version of this story,

“The Good Angel”,

is easily available in The Man Upstairs, this longer

version has not been collected in hardcovers. It has several points of interest:

1) Unlike “The Good Angel”, it takes place in America: there are references to

“president”, “Wall Street”, “New York”.

2) While other character names are the same in both versions, Rossiter’s first

name is “Marvin” in this story instead of “Martin” in “The Good Angel.”

3) It is Wodehouse’s first known use of the name “Lord Emsworth”, as one of

Keggs’s previous employers. This was not the ninth Earl of the Blandings Castle

stories but one of his predecessors; see the appendix to volume 8 of The

Millennium Wodehouse Concordance for a discussion.

4) Havant, one of the names of the whiskey-loving heir to Lord Emsworth,

is the name of a town in Hampshire just a couple of miles from the village

of Emsworth, just as Bosham is a town three or four miles in the other direction.

5) The Bachelors’ Club is mentioned; see Chapter 21 of N. T. P. Murphy’s A

Wodehouse Handbook for more details on this real-life club, often cited by

Wodehouse before he invented the Drones Club.

6) The use of “gray matter” referring to problem-solving skills is interesting

this early in fiction. Not for another ten years would Agatha Christie’s

Hercule Poirot popularize his “little grey cells”.

7) This American story has Marvin reading a soothing advertisement for Langley

and Fielding’s baked beans to Elsa in the last scene. In “The Good Angel” the

product advertised is Langley and Fielding’s sardines.

Comments about both versions of the story:

Wodehouse reused the plot element of the matrimonial sweepstakes

in A Damsel in Distress, and would also reuse the idea of a sunset

looking like a slice of rare (or underdone) beef many times, notably in Bertie’s

comment about Bingo Little’s attitude toward sunsets in The Code of the

Woosters, Percy Gorringe’s “Caliban at Sunset” in Jeeves and the Feudal

Spirit and Gussie Fink-Nottle’s comment in Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums