Cosmopolitan, September 1928

THE conversation in the bar-parlor of the Anglers’ Rest, which always tends to get deepish towards closing time, had turned to the subject of the Modern Girl; and a Gin-and-Ginger-ale sitting in the corner by the window remarked that it was strange how types die out.

“I can remember the days,” said the Gin-and-Ginger-ale, “when every other girl you met stood about six feet two in her dancing-shoes and had as many curves as a scenic railway. Now they are all five foot nothing and you can’t see them sideways. Why is this?”

The Draft Stout shook his head. “Nobody can say. It’s the same with dogs. One moment, the world is full of pugs as far as the eye can reach; the next, not a pug in sight, only Pekes and Alsatians. Odd!”

The Small Bass and the Double-Whisky-and-Splash admitted that these things were very mysterious and supposed we never should know the reason for them. Probably we were not meant to know.

“I cannot agree with you, gentlemen,” said Mr. Mulliner. He had been sipping his hot Scotch and lemon with a rather abstracted air, but now he sat up alertly, prepared to deliver judgment. “The reason for the disappearance of the dignified, queenly type of girl is surely obvious. It is nature’s method of insuring the continuance of the species. A world full of the sort of young women that Meredith used to put into his novels and du Maurier into his pictures in Punch would be a world full of permanent spinsters. The modern young man would never be able to summon up the nerve to propose to them.”

“Something in that,” assented the Draft Stout.

“I speak with authority on the point,” said Mr. Mulliner, “because my nephew Archibald made me his confidant when he fell in love with Aurelia Cammarleigh. He worshiped that girl with a fervor which threatened to unseat his reason, such as it was; but the mere idea of asking her to be his wife gave him, he informed me, such a feeling of faintness that only by means of a very stiff brandy and soda, or some similar restorative, was he able to pull himself together on the occasions when he contemplated it.

“Had it not been for—— But perhaps you would care to hear the story from the beginning?”

People who enjoyed a merely superficial acquaintance with my nephew Archibald (said Mr. Mulliner) were accustomed to set him down as just an ordinary pin-headed young man. It wras only when they came to know him better that they discovered their mistake. Then they realized that his pin-headedness, so far from being ordinary, was exceptional.

Even at the Drones’ Club, where the average of intellect is not high, it was often said of Archibald that, had his brain been constructed of silk, he would have been hard put to it to find sufficient material to make a canary a pair of stockings. He sauntered through life with a cheerful insouciance, and up to the age of twenty-five only once had been moved by anything in the nature of a really strong emotion—on the occasion when, in the heart of Bond Street and at the height of the London season, he discovered that his man Meadows had carelessly sent him out with odd spats on.

And then he met Aurelia Cammarleigh.

And then he met Aurelia Cammarleigh.

The first encounter between these two always has seemed to me to bear an extraordinary resemblance to the famous meeting between the poet Dante and Beatrice Portinari. Dante, if you remember, exchanged no remarks with Beatrice on that occasion. Nor did Archibald with Aurelia.

Dante just goggled at the girl. So did Archibald. Like Archibald, Dante loved at first sight; and the poet’s age at the time was, we are told, nine—which was almost exactly the mental age of Archibald Mulliner when he first set eye-glass on Aurelia Cammarleigh.

Only in the actual locale of the encounter do the two cases cease to be parallel. Dante, the story relates, was walking on the Ponte Vecchio, while Archibald Mulliner was having a thoughtful cocktail in the window of the Drones’ Club looking out on Dover Street.

And he had just relaxed his lower jaw in order to examine Dover Street more comfortably when there swam into his line of vision something that looked like a Greek goddess who, contrary to the usual practise of Greek goddesses, had had time to put some clothes on. She came out of a shop opposite the club and stood on the pavement waiting for a taxi. And, as he saw her standing there, love at first sight seemed to go all over Archibald Mulliner like the nettle-rash.

It was strange that this should have been so, for she was not at all the sort of girl with whom Archibald had fallen in love at first sight in the past. I chanced, while in here the other day, to pick up a copy of one of the old yellow-back novels of fifty years ago—the property, I believe, of Miss Postlethwaite, our courteous and erudite barmaid.

It was entitled “Sir Ralph’s Secret,” and its heroine, the Lady Elaine, was described as a superbly handsome girl, divinely tall, with a noble figure, the arched Montresor nose, haughty eyes beneath delicately penciled brows, and that indefinable air of aristocratic aloofness which marks the daughter of a hundred earls.

And Aurelia Cammarleigh might have been this formidable creature’s double.

Yet Archibald, sighting her, reeled as if the cocktail he had just consumed had been his tenth, instead of his first.

“Golly!” he said.

To save himself from falling, he had clutched at a passing fellow member; and now, examining his catch, he saw that it was young Algy Wymondham-Wymondham. Just the fellow member he would have preferred to clutch at, for Algy was a man who went everywhere and knew everybody and doubtless could give him the information he desired.

“Algy, old prune,” said Archibald in a low, throaty voice, “a moment of your valuable time, if you don’t mind.”

He paused, for he had perceived the need for caution. Algy was a notorious babbler, and it would be the height of rashness to give him an inkling of the passion which blazed within his breast. With a strong effort, he donned the mask. When he spoke again, it was with a deceiving nonchalance.

“I was just wondering if you happened to know who that girl is, across the street there. Seems to me I’ve met her somewhere or something or seen her or something. Or something, if you know what I mean.”

Algy followed his pointing finger and was in time to observe Aurelia as she disappeared into the cab.

“That girl?”

“Yes,” said Archibald, yawning. “Who is she, if any?”

“Girl named Cammarleigh.”

“Ah?” said Archibald, yawning again. “Then I haven’t met her.”

“Introduce you if you like. She’s sure to be at Ascot. Look out for us there.”

Archibald yawned for the third time.

“All right,” he said, “I’ll try to remember. Tell me about her. I mean, has she any fathers or mothers or any rot of that description?”

“Only an aunt. She lives with her in Park Street. She’s potty.”

Archibald started, stung to the quick.

“Potty? That divine—I mean, that rather attractive-looking girl?”

“Not Aurelia. The aunt. She thinks Bacon wrote Shakespeare.”

“Thinks who wrote what?” asked Archibald, puzzled, for the names were strange to him.

“You must have heard of Shakespeare. He’s well-known. Fellow who used to write plays. Only Aurelia’s aunt says he didn’t. She maintains that a bloke called Bacon wrote them for him.”

“Dashed decent of him,” said Archibald approvingly. “Of course, he may have owed Shakespeare money.”

“There’s that, of course.”

“What was the name again?”

“Bacon.”

“Bacon,” said Archibald, jotting it down on his cuff. “Right.”

Algy moved on, and Archibald, his soul bubbling within him like a Welsh rabbit at the height of its fever, sank into a chair and stared sightlessly at the ceiling. Then, rising, he went off to the Burlington Arcade to buy socks.

The process of buying socks eased for a while the turmoil that ran riot in Archibald’s veins. But even socks with violet clocks can only alleviate; they do not cure. Returning to his rooms, he found the anguish rather more overwhelming than ever. For at last he had leisure to think; and thinking always hurt his head.

Algy’s careless words had confirmed his worst suspicions. A girl with an aunt who knew all about Shakespeare and Bacon must of necessity live in a mental atmosphere into which a lame-brained bird like himself scarcely could hope to soar. Even if he did meet her—even if she asked him to call—even if in due time their relations became positively cordial, what then? How could he aspire to such a goddess? What had he to offer her?

Money?

Plenty of that, yes, but what was money?

Socks?

Of these he had the finest collection in London, but socks are not everything.

A loving heart? A fat lot of use that was.

No, a girl like Aurelia Cammarleigh would, he felt, demand from the man who aspired to her hand something in the nature of gifts, of accomplishments. He would have to be a man who Did Things.

And what, Archibald asked himself, could he do? Absolutely nothing except give an imitation of a hen laying an egg.

That he could do. At imitating a hen laying an egg he was admittedly a master. His fame in that one respect had spread all over the West End of London. “Others abide our question. Thou art free,” was the verdict of London’s gilded youth on Archibald Mulliner when considered purely in the light of a man who could imitate a hen laying an egg. “Mulliner,” they said to one another, “may be a pretty total loss in many ways, but he can imitate a hen laying an egg.”

And, so far from helping him, this one accomplishment of his would, reason told him, be a positive handicap. A girl like Aurelia Cammarleigh would simply be sickened by such coarse buffoonery.

He blushed at the very thought of her ever learning that he was capable of sinking to such depths.

And so, when some weeks later he was introduced to her in the paddock at Ascot and she, gazing at him with what seemed to his sensitive mind contemptuous loathing, said:

“They tell me you give an imitation of a hen laying an egg, Mr. Mulliner.”

He replied with extraordinary vehemence:

“It is a lie—a foul and contemptible lie which I shall track to its source and nail to the counter.”

Brave words! But had they clicked? Had she believed him? He trusted so. But her haughty eyes were very penetrating. They seemed to pierce through to the depths of his soul and lay it bare for what it was—the soul of a hen-imitator.

However, she did ask him to call. With a sort of queenly, bored disdain and only after he had asked twice if he might—but she did it. And Archibald resolved that, no matter what the mental strain, he would show her that her first impression of him had been erroneous; that, trivial and vapid though he might seem, there were in his nature deeps whose existence she had not suspected.

For a young man who had been superannuated from Eton and believed everything he read in the Racing Expert’s column in the morning paper, Archibald, I am bound to admit, exhibited in this crisis a sagacity for which few of his intimates would have given him credit. It may be that love stimulates the mind, or it may be that when the moment comes Blood will tell.

Archibald, you must remember, was, after all, a Mulliner; now the old resourceful strain of the Mulliners came out in him.

“Meadows,” he said to Meadows, his man.

“Sir?” said Meadows.

“It appears,” said Archibald, “that there is—or was—a cove of the name of Shakespeare. Also a second cove of the name of Bacon. And Bacon wrote plays, it seems, and Shakespeare went and put his own name on the program and copped the credit.”

“Indeed, sir?”

“If true, not right, Meadows.”

“Far from it, sir.”

“Very well, then. I wish to go into this matter carefully. Kindly pop out and get me a book or two bearing on the business.”

He had planned his campaign with infinite cunning. He knew that, before anything could be done in the direction of winning the heart of Aurelia Cammarleigh, he must first establish himself solidly with the aunt. He must court the aunt, ingratiate himself with her—always, of course, making it clear from the start that she was not the one. And if reading about Shakespeare and Bacon could do it, he would, he told himself, have her eating out of his hand in a week.

Meadows returned with a parcel of forbidding-looking volumes, and Archibald put in a fortnight’s intensive study. Then, discarding the monocle which had up till then been his constant companion and substituting for it a pair of horn-rimmed spectacles which gave him something of the look of an earnest sheep, he set out for Park Street to pay his first call. And within five minutes of his arrival he had declined a cigaret on the plea that he was a non-smoker and had managed to say some rather caustic things about the practise, so prevalent among his contemporaries, of drinking cocktails.

Life, said Archibald, toying with his teacup, was surely given to us for some better purpose than the destruction of our brains and digestion with alcohol. Bacon, for instance, never took a cocktail in his life, and look at him.

At this, the aunt, who up till now plainly had been regarding him as just another of those unfortunate incidents, sprang to life.

“You admire Bacon, Mr. Mulliner?” she asked eagerly.

And reaching out an arm like the tentacle of an octopus, she drew him into a corner and talked about Cryptograms for forty-seven minutes by the drawing-room clock. In short, to sum the thing up, my nephew, Archibald, at his initial meeting with the only relative of the girl he loved, went like a breeze. A Mulliner is always a Mulliner. Apply the acid test, and he will meet it.

It was not long after this that he informed me that he had sown the good seed to such an extent that Aurelia’s aunt had invited him to pay a long visit to her country house, Brawstead Towers in Sussex.

He was seated at the Savoy bar when he told me this, rather feverishly putting himself outside a Scotch and soda, and I was perplexed to note that his face was drawn and his eyes were haggard.

“But you do not seem happy, my boy,” I said.

“I’m not happy.”

“But surely this should be an occasion for rejoicing. Thrown together as you will be in the pleasant surroundings of a country house, you ought easily to find an opportunity of asking this girl to marry you.”

“And a lot of good that will be,” said Archibald moodily. “Even if I do get a chance I shan’t be able to make any use of it. I wouldn’t have the nerve. You don’t seem to realize what it means being in love with a girl like Aurelia.

“When I look into those clear, soulful eyes or see that perfect profile bobbing about on the horizon, a sense of my unworthiness seems to slosh me amidships like some blunt instrument. My tongue gets entangled with my front teeth, and all I can do is stand there feeling like a piece of Gorgonzola that has been condemned by the local sanitary inspector.

“I’m going to Brawstead Towers, yes, but I don’t expect anything to come of it. I know exactly what’s going to happen to me. I shall just buzz along through life, pining dumbly, and in the end slide into the tomb a blasted, blighted bachelor. Another whisky, please, and jolly well make it a double.”

Brawstead Towers, situated as it is in the pleasant Weald of Sussex, stands some fifty miles from London; and Archibald, taking the trip easily in his car, arrived there in time to dress comfortably for dinner.

It was only when he reached the drawing-room at eight o’clock that he discovered that the younger members of the house-party had gone off in a body to dine and dance at a hospitable neighbor’s, leaving him to waste the evening tie of a lifetime, to the composition of which he had devoted no less than twenty-two minutes, on Aurelia’s aunt.

Dinner in these circumstances hardly could hope to be an unmixedly exhilarating function. Among the things which helped to differentiate it from a Babylonian orgy was the fact that, in deference to his known prejudice, no wine was served to Archibald. And lacking artificial stimulus, he found the aunt even harder to endure philosophically than ever.

Archibald long since had come to a definite decision that what this woman needed was an ounce of weed-killer, scientifically administered. With a good deal of adroitness he contrived to head her off from her favorite topic during the meal; but after the coffee had been disposed of she threw off all restraint. Scooping him up and bearing him off into the recesses of the west wing, she wedged him into a comer of a settee and began to tell him all about the remarkable discovery which had been made by applying the Plain Cipher to Milton’s well-known “Epitaph on Shakespeare.”

“The one beginning ‘What needs my Shakespeare for his honoured bones,’ ” said the aunt.

“Oh, that one?” said Archibald.

“ ‘What needs my Shakespeare for his honoured bones? The labour of an Age in pilèd stones? Or that his hallowed reliques should be hid under a starry-pointing pyramid?’ ” said the aunt.

Archibald, who was not good at riddles, said he didn’t know.

“As in the plays and sonnets,” said the aunt, “we substitute the name equivalents of the figure totals.”

“We do what?”

“Substitute the name equivalents of the figure totals!”

“The which?”

“The figure totals.”

“All right,” said Archibald. “Let it go. I dare say you know best.”

The aunt inflated her lungs.

“These figure totals,” she said, “are always taken out in the Plain Cipher, A equaling one to Z equals twenty-four. The names are counted in the same way. A capital letter with the figures indicates an occasional variation in the Name Count. For instance, A equals twenty-seven, B twenty-eight, until K equals ten is reached, when K instead of ten becomes one and T instead of nineteen is one and R or Reverse and so on, until A equals twenty-four is reached. The short or single Digit is not used here.

“Reading the Epitaph in the light of this Cipher, it becomes: ‘What need Verulam for Shakespeare? Francis Bacon England’s King be hid under a W. Shakespeare? William Shakespeare. Fame, what needst Francis Tudor, King of England? Francis. Francis. W. Shakespeare. For Francis thy William Shakespeare hath England’s King took W. Shakespeare. Then thou our W. Shakespeare Francis Tudor bereaving Francis Bacon Francis Tudor such a tomb William Shakespeare.’ ”

The speech to which he had been listening was unusually lucid and simple for a Baconian, yet Archibald, his eye catching a battle-ax that hung on the wall, could not but stifle a wistful sigh. How simple it would have been, had he not been a Mulliner and a gentleman, to remove the weapon from its hook, spit on his hands, and haul off and dot this doddering old ruin one just above the imitation pearl necklace.

Placing his twitching hands underneath him and sitting on them, he stayed where he was until, just as the clock on the mantelpiece chimed the hour of midnight, a merciful fit of hiccups on the part of his hostess enabled him to retire. As she reached the twenty-seventh “hic,” his fingers found the door-handle and a moment later he was outside, streaking up the stairs.

The room they had given Archibald was at the end of a corridor, a pleasant, airy apartment with French windows opening upon a broad balcony. At any other time he would have found it agreeable to hop out onto this balcony and revel in the scents and sounds of the summer night, thinking the while long, lingering thoughts of Aurelia. But what with all that Francis Tudor Francis Bacon such a tomb William Shakespeare count seventeen drop one knit purl and set them up in the other alley stuff, not even thoughts of Aurelia could keep him from his bed.

Moodily tearing off his clothes and donning his pajamas, Archibald Mulliner climbed in and instantaneously discovered that the bed was an apple-pie bed. When and how it had happened he did not know, but at a point during the day some loving hand had sewn up the sheets and put two hair-brushes and a branch of some prickly shrub between them.

Himself from earliest boyhood an adept at the construction of booby-traps, Archibald, had his frame of mind been sunnier, doubtless would have greeted this really extremely sound effort with a cheery laugh. As it was, weighed down with Verulams and Francis Tudors, he swore for a while with considerable fervor; then, ripping off the sheets and tossing the prickly shrub wearily into a corner, he crawled between the blankets and was soon asleep.

His last waking thought was that if the aunt hoped to catch him on the morrow, she would have to be considerably quicker on her pins than her physique indicated.

How long Archibald slept he could not have said. He woke some hours later with a vague feeling that a thunder-storm of unusual violence had broken out in his immediate neighborhood. But this, he realized as the mists of slumber cleared away, was an error. The noise which had disturbed him was not thunder but the sound of someone snoring. Snoring like the dickens. The walls seemed to be vibrating like the deck of an ocean liner.

Archibald Mulliner might have had a tough evening with the aunt, but his spirit was not so completely broken as to make him lie supinely down beneath that snoring. The sound filled him, as snoring fills every right-thinking man, with a seething resentment and a passionate yearning for justice, and he climbed out of bed with the intention of taking the proper steps through the recognized channels.

It is the custom nowadays to disparage the educational methods of the English public school and to maintain that they are not practical and of a kind to fit the growing boy for the problems of after-life. But you do learn one thing at a public school, and that is how to act when somebody starts snoring.

You jolly well grab a cake of soap and pop in and stuff it down the blighter’s throat. And this Archibald proposed to do. It was the work of a moment with him to dash to the wash-stand and arm himself. Then he moved softly out through the windows onto the balcony.

The snoring, he had ascertained, proceeded from the next room. Presumably this room also would have French windows; and presumably, as the night was warm, these would be open. It would be a simple task to oil in, insert the soap and buzz back undetected.

It was a lovely night, but Archibald paid no attention to it. Clasping his cake of soap, he crept on and was pleased to discover, on arriving outside the snorer’s room, that his surmise had been correct. The windows were open. Beyond them, screening the interior of the room, were heavy curtains. And he had just placed his hand upon these when from inside a voice spoke. At the same moment the light was turned on.

“Who’s that?” said the voice.

And it was as if Brawstead Towers with all its stabling, outhouses and messuages had fallen on Archibald’s head. A mist rose before his eyes. He gasped and tottered.

The voice was that of Aurelia Cammarleigh.

For an instant, for a single long, sickening instant, I am compelled to admit that Archibald’s love, deep as the sea though it was, definitely wabbled. It had received a grievous blow. It was not simply the discovery that the girl he adored was a snorer that unmanned him: it was the thought that she could snore like that. There was something about those snores that had seemed to sin against his whole conception of womanly purity, so eloquent were they of adenoids that should have been removed in infancy and tonsils that ought never to have been allowed to remain untended.

Then he recovered. Even though this girl’s slumber was not, as the poet Milton so beautifully puts it, “airy light” but rather reminiscent of a lumber-camp when the wood-sawing is proceeding at its briskest, he loved her still.

He had just reached this conclusion when a second voice spoke inside the room.

“I say, Aurelia.”

It was the voice of another girl. He perceived now that the question “Who’s that?” had been addressed not to him but to this newcomer fumbling at the door-handle.

“I say, Aurelia,” said the girl complainingly, “you’ve simply got to do something about that bally bulldog of yours. I can’t possibly get to sleep with him snoring like that. He’s making the plaster come down from the ceiling in my room.”

“I’m sorry,” said Aurelia. “I’ve got so used to it that I don’t notice.”

“Well, I do. Put a green-baize cloth over him or something.”

Out on the moonlit balcony Archibald Mulliner stood shaking like a blanc-mange. Although he had contrived to maintain his great love practically intact when he had supposed the snores to proceed from the girl he worshiped, it had been tough going and for an instant, as I have said, a very near thing.

The relief that swept over him at the discovery that Aurelia could still justifiably remain on her pinnacle was so profound that it made him feel filleted. He seemed for a moment in a daze. Then he was brought out of the ether by hearing his name spoken.

“Did Archie Mulliner arrive tonight?” asked Aurelia’s friend.

“I suppose so,” said Aurelia. “He wired that he was motoring down.”

“Just between us girls,” said Aurelia’s friend, “what do you think of that bird?”

To listen in on a private conversation—especially a private conversation between two modern girls when you never know what may come next—is rightly considered an action incompatible with the claim to be a gentleman. I regret to say, therefore, that Archibald, ignoring the fact that he belonged to a family whose code is as high as that of any in the land, instead of creeping away to his room edged at this point a step closer to the curtains and stood there with his ears flapping.

It might be an ignoble thing to eavesdrop, but it was apparent that Aurelia Cammarleigh was about to reveal her candid opinion of him; and the prospect of getting the true facts—straight, as it were, from the horse’s mouth—held him so fascinated that he could not move.

“Archie Mulliner?” said Aurelia meditatively.

“Yes. The betting at the Junior Lip-stick is seven to two that you’ll marry him.”

“Why on earth?”

“Well, people have noticed he’s always round at your place and they seem to think it significant. Anyway, that’s how the odds stood when I left London—seven to two.”

“Get in on the short end,” said Aurelia earnestly, “and you’ll make a packet.”

“Is that official?”

“Absolutely,” said Aurelia.

Out in the moonlight, Archibald Mulliner uttered a low bleak moan rather like the last bit of wind going out of a dying duck. True, he had always told himself that he hadn’t a chance, but however much a man may say that, he never in his heart really believes it. And now from an authoritative source he had learned that his romance was definitely blue round the edges.

It was a shattering blow. He wondered dully how the trains ran to the Rocky Mountains. A spot of grizzly-bear shooting seemed indicated.

Inside the room, the other girl appeared perplexed.

“But you told me at Ascot,” she said, “just after he had been introduced to you, that you rather thought you had at last met your ideal. When did the good thing begin to come unstuck?”

A silvery sigh came through the curtains.

“I did think so then,” said Aurelia wistfully. “There was something about him. I liked the way his ears wiggled. And I had always heard he was such a perfectly genial, cheery, merry old soul. Algy Wymondham-Wymondham told me that his imitation of a hen laying an egg was alone enough to keep any reasonable girl happy through a long married life.”

“Can he imitate a hen?”

“No. I asked him, and he stoutly denied that he had ever done such a thing in his life. He was quite stuffy about it. I felt a little uneasy then, and the moment he started calling and hanging about the house I knew that my fears had been well-founded. The man is beyond question a flat tire and a wet smack.”

“As bad as that?”

“I’m not exaggerating a bit. Where people ever got the idea that Archie Mulliner is a bonhomous old bean beats me. He is the world’s worst monkey-wrench. He doesn’t drink cocktails, he doesn’t smoke cigarets, and the thing he seems to enjoy most in the world is to sit for hours listening to the conversation of my aunt, who, as you know, is pure goof from the soles of the feet to the tortoise-shell comb and should long ago have been renting a padded cell in Earlswood. Believe me, Muriel, if you really can get seven to two, you are onto the best thing since Buttercup won the Lincolnshire.”

“You don’t say!”

“I do say. Apart from anything else, he’s got a beastly habit of looking at me reverently. And if you knew how sick I am of being looked at reverently! They will do it, these lads. I suppose it’s because I’m rather an out-size and modeled on the lines of Cleopatra.”

“Tough!”

“You bet it’s tough. A girl can’t help her appearance. I may look as if my ideal man was the hero of a Viennese operetta, but I don’t feel that way. What I want is some good sprightly sportsman who sets a neat booby-trap and who’ll rush up and grab me in his arms and say to me ‘Aurelia, old girl, you’re the bee’s roller-skates!’ ”

And Aurelia emitted another sigh.

“Talking of booby-traps,” said the other girl, “if Archie Mulliner has arrived he’s in the next room, isn’t he?”

“I suppose so. That’s where he was to be. Why?”

“Because I made him an apple-pie bed.”

“It was the right spirit,” said Aurelia warmly. “I wish I’d thought of it myself.”

“Too late now.”

“Yes,” said Aurelia. “But I’ll tell you what I can and will do. You say you object to Lysander’s snoring. Well, I’ll go and pop him in at Archie Mulliner’s window. That’ll give him pause for thought.”

“Splendid,” agreed the girl Muriel. “Well, good night.”

“Good night,” said Aurelia.

There followed the sound of a door closing.

There was, as I have indicated, not much of my nephew Archibald’s mind, but what there was of it was now in a whirl. He was stunned. Large though his ears were, he could hardly believe them. Like every man who is abruptly called upon to revise his entire scheme of values, he felt as if he had been standing on top of the Eiffel Tower and some practical joker had suddenly drawn it away from under him.

Tottering back to his room, he replaced the cake of soap in its dish and sat down on the bed to grapple with this amazing development.

Aurelia Cammarleigh had compared herself to Cleopatra. It is not too much to say that my nephew Archibald’s emotions at this juncture were very similar to what Mark Antony’s would have been had Egypt’s queen risen from her throne at his entry and without a word of warning started to dance the Black Bottom.

He was roused from his thoughts by the sound of a light footstep on the balcony outside. At the same moment, he heard a low woofly gruffle, the unmistakable note of a bulldog of regular habits who has been jerked out of his basket in the small hours and forced to take the night air.

“She is coming, my own, my sweet;

Were it ever so airy a tread,

My heart would hear her and beat,

Were it earth in an earthy bed,”

whispered Archibald’s soul, or words to that effect. He rose from his seat and paused for an instant, irresolute. Then inspiration descended on him. He knew what to do, and he did it.

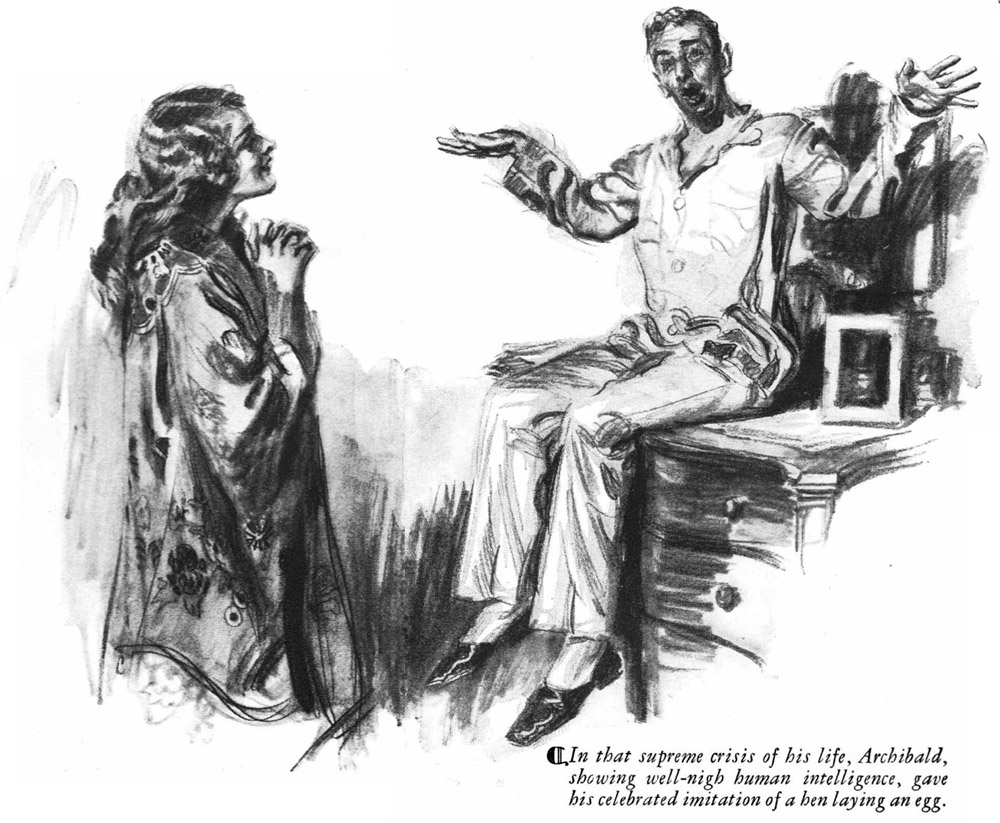

Yes, gentlemen, in that supreme crisis of his life, with his whole fate hanging, as you might say, in the balance, Archibald Mulliner, showing for almost the first time in his career a well-nigh human intelligence, began to give his celebrated imitation of a hen laying an egg.

Archibald’s imitation of a hen laying an egg was conceived on broad and sympathetic lines. Less violent than Salvini’s “Othello,” it had in it something of the poignant wistfulness of Mrs. Siddons in the sleep-walking scene of “Macbeth.” The rendition started quietly, almost inaudibly, with a sort of soft, liquid crooning—the joyful yet half-incredulous murmur of a mother who scarcely can believe as yet that her union really has been blessed and that it is indeed she who is responsible for that oval mixture of chalk and albumen which she sees lying beside her in the straw.

Then, gradually, conviction comes.

“It looks like an egg,” one seems to hear her say. “It feels like an egg. It’s shaped like an egg. Damme, it is an egg!”

And at that, all doubting resolved, the crooning changes; takes on a firmer note; soars into the upper register; and finally swells into a maternal pæan of joy—a “Charawk-chawk-chawk-chawk” of such a caliber that few had ever been able to listen to it dry-eyed. Following which, it was Archibald’s custom to run round the room, flapping the sides of his coat, and then, leaping onto a sofa or some convenient chair, to stand there with his arms at right angles, crowing himself purple in the face.

All these things he had done many a time for the idle entertainment of fellow members in the smoking-room of the Drones, but never with the gusto, the brio, with which he performed them now. Essentially a modest man, like all the Mulliners, he was compelled to recognize that tonight he was surpassing himself.

Every artist knows when the authentic divine fire is within him, and an inner voice told Archibald Mulliner that he was at the top of his form and giving the performance of a lifetime. Love thrilled through every “Brt-t’t-t’t” that he uttered, animated each flap of his arms. Indeed, so deeply did Love drive in its spur that he tells me that, instead of the customary once, he actually made the circle of the room three times before coming to rest on top of the chest of drawers.

When at length he did so he glanced towards the window and saw that through the curtains the loveliest face in the world was peering. And in Aurelia Cammarleigh’s glorious eyes there was a look he never had seen before, the sort of look Kreisler or somebody like that beholds in the eyes of the front row as he lowers his violin. A look of worship.

There was a long silence. Then she spoke.

“Do it again!” she said.

And Archibald did it again. He did it four times and could, he tells me, if he had pleased, have taken a fifth encore or at any rate a couple of bows. And then, leaping lightly to the floor, he advanced towards her. He felt conquering, dominant. It was his hour. He reached out and clasped her in his arms.

“Aurelia, old girl,” said Archibald in a clear, firm voice, “you are the bee’s roller-skates.”

And at that, she seemed to melt into his embrace. Her lovely face was raised to his.

“Archibald!” she whispered.

There was another throbbing silence, broken only by the beating of two hearts and the wheezing of the bulldog, who seemed to suffer a good deal in his bronchial tubes. Then Archibald released her.

“Well, that’s that,” he said. “Glad everything’s all settled and hotsy-totsy. Gosh, I wish I had a cigaret. This is the sort of moment a bloke needs one.”

She looked at him surprised. “But I thought you didn’t smoke.”

“Oh yes, I do.”

“And do you drink as well?”

“Quite as well,” said Archibald. “In fact, rather better. Oh, by the way.”

“Yes?”

“There’s just one other thing. Suppose that aunt of yours wants to come and visit us when we are settled down in our little nest, what, dearest, would be your reaction to the scheme of soaking her on the base of the skull with a stuffed eelskin?”

“I should like it,” said Aurelia warmly, “above all things.”

“Twin souls!” cried Archibald. “That’s what we are, when you come right down to it. I suspected it all along, and now I know. Two jolly old twin souls.” He embraced her ardently. “And now,” he said, “let us pop downstairs and put this bulldog in the butler’s pantry, where he will come upon him unexpectedly in the morning and doubtless get a shock which will do him as much good as a week at the seaside. Are you on?”

“I am,” whispered Aurelia. “Oh, I am!”

And hand in hand they wandered out together onto the broad staircase.

Printer’s errors corrected above:

p. 46b: Magazine omitted “ before “And a lot of good”

p. 47a: Magazine had extra ’ after “honoured bones?”; the quotation concludes after “pyramid?”

Annotations to this story as it appeared in book form are in the notes to Mr. Mulliner Speaking on this site.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums