Cosmopolitan, February 1921

THE summer morning was so brilliantly fine, the populace popped to and fro in so active and cheery a manner, and everybody appeared to be so absolutely in the pink that a casual observer of the city of New York would have said that it was one of those happy days. Yet Archie Moffam, as he turned out of the sun-bathed street into the ramshackle building on the third floor of which was the studio belonging to his artist friend, James B. Wheeler, was faintly oppressed with a sort of a kind of feeling that something was wrong. He would not have gone so far as to say that he had the pip—it was more a vague sense of discomfort. And, searching for first causes as he made his way up-stairs, he came to the conclusion that the person responsible for this nebulous depression was his wife, Lucille. It seemed to Archie that, at breakfast that morning, Lucille’s manner had been subtly rummy. Nothing you could put your finger on, still—rummy.

Musing thus, he reached the studio, and found the door open and the room empty. It had the air of a room whose owner has dashed in to fetch his golf-clubs and biffed off, after the casual fashion of the artist-temperament, without bothering to close up behind him. And such, indeed, was the case. The studio had seen the last of J. B. Wheeler for that day; but Archie, not realizing this, and feeling that a chat with Mr. Wheeler, who was a light-hearted bird, was what he needed this morning, sat down to wait. After a few moments, his gaze, straying over the room, encountered a handsomely framed picture, and he went across to take a look at it.

J. B. Wheeler was an artist who made a large annual income as an illustrator for the magazines, and it was a surprise to Archie to find that he also went in for this kind of thing. For the picture, dashingly painted in oils, represented a comfortably plump young woman who, from her rather weak-minded simper and the fact that she wore absolutely nothing except a dove on the left shoulder, was plainly intended to be the goddess Venus. Archie was not much of a nib round the picture-galleries, but he knew enough about art to recognize Venus when he saw her; though once or twice, it is true, artists had double-crossed him by ringing in some such title as “Day-Dreams” or “When The Heart Is Young.”

He inspected this picture for a while, then, returning to his seat, lighted a cigarette and began to meditate on Lucille once more. Yes; the dear girl had been rummy at breakfast. She had not exactly said anything or done anything out of the ordinary, but—well, you know how it is. We husbands—we lads of the for-better-or-for-worse brigade—we learn to pierce the mask. There had been in Lucille’s manner that curious, strained sweetness which comes to women whose husbands have failed to match the piece of silk or forgotten to post an important letter. If his conscience had not been as clear as crystal, Archie would have said that that was what must have been the matter. But when Lucille wrote letters, she just stepped out of the suite and dropped them in the mail-chute attached to the elevator. It couldn’t be that. And he couldn’t have forgotten anything else, because——

“O my sainted aunt!”

Archie’s cigarette smoldered, neglected, between his fingers. His jaw had fallen, and his eyes were staring glassily before him. He was appalled. His memory was weak, he knew; but never before had it let him down so scurvily as this. This was a record. It stood in a class by itself, printed in red ink, and marked with a star as the bloomer of a lifetime. For a man may forget many things—he may forget his name, his umbrella, his nationality, his spats, and the friends of his youth; but there is one thing which your married man, your in-sickness-and-in-health lizard must not forget, and that is the anniversary of his wedding-day.

Remorse swept over Archie like a wave. His heart bled for Lucille. No wonder the poor girl had been rummy at breakfast! What girl wouldn’t be rummy at breakfast, tied for life to a ghastly outsider like himself? He groaned hollowly and sagged forlornly in his chair, and, as he did so, the Venus caught his eye. For it was an eye-catching picture. You might like it or dislike it, but you could not ignore it.

Archie’s soul rose suddenly from the depths to which it had descended. He did not often get inspirations, but he got one now. Hope dawned with a jerk. The one way out had presented itself to him. A rich present! That was the wheeze. If he returned to her, bearing a rich present, he might, with the help of heaven and a face of brass, succeed in making her believe that he had merely pretended to forget the vital date in order to enhance the surprise.

It was a scheme. It was more—it was an egg. Archie had the whole binge neatly worked out inside a minute. He scribbled a note to Mr. Wheeler, explaining the situation, and promising reasonable payment on the instalment system; then, placing the note in a conspicuous position on the easel, he leaped to the telephone—and presently found himself connected with Lucille’s room at the Cosmopolis.

“Hullo, darling!” he cooed.

There was a slight pause at the other end of the wire.

“Oh, hullo, Archie!”

Lucille’s voice was dull and listless, and Archie’s experienced ear could detect that she had been crying.

“Many happy returns of the day, old thing!”

A muffled sob floated over the wire.

“Have you only just remembered?”

Archie, bracing himself up, cackled gleefully into the receiver.

“Did I take you in, light of my home? Do you mean to say you really thought I had forgotten? For heaven’s sake!”

“You didn’t say a word at breakfast.”

“Ah, but that was all part of the devilish cunning. I hadn’t got a present for you then. At least, I didn’t know whether it was ready.”

“Oh, Archie, you darling!” Lucille’s voice had lost its crushed melancholy. She trilled like a thrush, or a linnet, or any bird that goes in largely for trilling. “Have you really got me a present?”

“It’s here now—the dickens of a fruity picture. One of J. B. Wheeler’s things. You’ll like it.”

“Oh, I know I shall! I love his work. You are an angel. We’ll hang it over the piano.”

“I’ll be round with it in something under three ticks, star of my soul. I’ll take a taxi.”

“Yes; do hurry! I want to hug you.”

“Right-o!” said Archie. “I’ll take two taxis.”

It is not far from Washington Square to the Hotel Cosmopolis, and Archie made the journey without mishap. There was a little unpleasantness with the cabman before starting—he, on the prudish plea that he was a married man with a local reputation to keep up, declining at first to be seen in company with the masterpiece. But, on Archie giving a promise to keep the front of the picture away from the public gaze, he consented to take the job on, and, some ten minutes later, having made his way blushfully through the hotel lobby and endured the frank curiosity of the boy who worked the elevator, Archie entered his suite, the picture under his arm.

He placed it carefully against the wall in order to leave himself more scope for embracing Lucille, and when the joyful reunion—or the sacred scene, if you prefer so to call it—was concluded, he stepped forward to turn it round and exhibit it.

“Why, it’s enormous!” said Lucille. “I didn’t know Mr. Wheeler ever painted pictures that size. When you said it was one of his, I thought it must be the original of a magazine drawing or something like— Oh!”

Archie had moved back and given her an uninterrupted view of the work of art, and Lucille had started as if some unkindly disposed person had driven a brad-awl into her.

Archie had moved back and given her an uninterrupted view of the work of art, and Lucille had started as if some unkindly disposed person had driven a brad-awl into her.

“Pretty ripe—what?” said Archie enthusiastically.

“Pretty ripe—what?” said Archie enthusiastically.

Lucille did not speak for a moment. It may have been sudden joy that kept her silent. Or, on the other hand, it may not. She stood looking at the picture with wide eyes and parted lips.

“A bird, eh?” said Archie.

“Y-yes,” said Lucille.

“I knew you’d like it,” proceeded Archie, with animation. “You see, you’re by way of being a picture-hound—know all about the things and what-not—inherit it from the dear old dad, I shouldn’t wonder. Personally, I can’t tell one picture from another as a rule, but think this will add a touch of distinction to the home—yes—no? I’ll hang it up, shall I? ’Phone down to the office, light of my soul, and tell them to send up a nail, a bit of string, and the hotel hammer.”

“One moment, darling. I’m not quite sure——”

“Eh?”

“Where it ought to hang, I mean. You see——”

“Over the piano, you said. The jolly old piano.”

“Yes; but I hadn’t seen it then.”

A monstrous suspicion flitted for an instant into Archie’s mind.

“I say, you do like it, don’t you?” he said anxiously.

“Oh, Archie darling, of course I do! And it was so sweet of you to give it to me. But, what I was trying to say was that this picture is so—so striking that I feel that we ought to wait a little while and decide where it would have the best effect. The light over the piano is rather strong.”

“You think it ought to hang in a dimmish light—what?”

“Yes, yes. The dimmer the—I mean, yes, in a dim light. Suppose we leave it in the corner for the moment—over there—behind the sofa, and—I’ll think it over.”

“Right-o! Here?”

“Yes; that will do splendidly. Oh—and Archie?”

“Hullo!”

“I think perhaps— Just turn its face to the wall, will you?” Lucille gave a little gulp. “It will prevent its getting dusty.”

It perplexed Archie a little during the next few days to notice in Lucille, whom he had always looked on as preeminently a girl who knew her own mind, a curious streak of vacillation. Quite half a dozen times he suggested various spots on the wall as suitable for the Venus, but Lucille seemed unable to decide. Archie wished that she would settle on something definite, for he wanted to invite J. B. Wheeler to the suite to see the thing. He had heard nothing from the artist since the day he had removed the picture, and one morning, encountering him on Broadway, he expressed his appreciation of the very decent manner in which the other had taken the whole affair.

“Oh, that!” said J. B. Wheeler. “My dear fellow, you’re welcome.” He paused for a moment. “More than welcome,” he added. “You aren’t much of an expert on pictures, are you?”

“Well,” said Archie, “I don’t know that you’d call me an absolute nib, don’t you know, but, of course, I know enough to see that this particular exhibit is not a little fruity. Absolutely one of the best things you’ve ever done, laddie!”

A slight purple tinge manifested itself in Mr. Wheeler’s round and rosy face. His eyes bulged.

“What are you talking about, you Tishbite? You misguided son of Belial, are you under the impression that I painted that thing?”

“Didn’t you?”

Mr. Wheeler swallowed a little convulsively.

“My fiancée painted it,” he said shortly.

“Your fiancée? My dear old lad, I didn’t know you were engaged. Who is she? Do I know her?”

“Her name is Alice Wigmore. You don’t know her.”

“And she painted that picture?” Archie was perturbed. “But, I say! Won’t she be apt to wonder where the thing has got to?”

“I told her it had been stolen. She thought it a great compliment, and was tickled to death. So that’s all right.”

“And, of course, she’ll paint you another.”

“Not while I have my strength she won’t,” said J. B. Wheeler firmly. “She’s given up painting since I taught her golf, thank goodness, and my best efforts shall be employed in seeing that she doesn’t have a relapse.”

“But, laddie,” said Archie, puzzled, “you talk as though there were something wrong with the picture. I thought it dashed hot stuff.”

“God bless you!” said J. B. Wheeler.

Archie proceeded on his way, still mystified. Then he reflected that artists, as a class, were all pretty weird and rummy, and talked more or less consistently through their hats. You couldn’t ever take an artist’s opinion on a picture. He had met several of the species who absolutely raved over things which any reasonable chappie would decline to be found dead with in a ditch. His admiration for the Wigmore Venus, which had faltered for a moment during his conversation with J. B. Wheeler, returned in all its pristine vigor.

At breakfast next morning, Archie once more brought up the question of the hanging of the picture. It was absurd to let a thing like that go on wasting its sweetness behind a sofa with its face to the wall.

“Touching the jolly old masterpiece,” he said, “how about it? I think it’s time we hoisted it up somewhere.”

Lucille fiddled pensively with her coffee-spoon.

“Archie dear,” she said, “I’ve been thinking.”

“And a very good thing to do,” said Archie.

“About that picture, I mean. Did you know it was father’s birthday to-morrow?”

“Why, no, old thing. I didn’t, to be absolutely honest. Your revered parent doesn’t confide in me much.”

“Well, it is. And I think we ought to give him a present.”

“Absolutely! But how? I’m all for spreading sweetness and light and cheering up the jolly old pater’s sorrowful existence, but I haven’t a bean. And, what is more, things have come to such a pass that I scan the horizon without seeing a single soul I can touch. I suppose I could get into Reggie van Tuyl’s ribs for a bit, but—I don’t know—touching poor old Reggie always seems to me rather like potting a sitting bird.”

“Of course I don’t want you to do anything like that. I was thinking—Archie darling, would you be very hurt if I gave father the picture?”

“Oh, I say!”

“Well, I can’t think of anything else.”

“But wouldn’t you miss it most frightfully?”

“Oh, of course I should. But, you see—father’s birthday——”

Archie had always thought Lucille the dearest and most unselfish angel in the world, but never had the fact come home to him so forcibly as now. He kissed her fondly.

“By Jove!” he exclaimed. “You really are, you know! This is the biggest thing since jolly old Sir Philip What’s-his-name gave the drink of water to the poor blighter whose need was greater than his, if you recall the incident. I had to sweat it up at school, I remember. Sir Philip, poor old bean, had a most ghastly thirst on, and he was just going to have one on the house, so to speak, when—but it’s all in the history-books. This is the sort of thing boy scouts do. Well, of course, it’s up to you, queen of my soul. If you feel like making the sacrifice, right-o! Shall I bring the pater up here and show him the picture?”

“No; I wouldn’t do that. Do you think you could get into his suite to-morrow morning and hang it up somewhere? You see, if he had the chance of—what I mean is, if—yes; I think it would be best to hang it up and let him discover it there.”

“It would give him a surprise, you mean—what?”

“Yes.”

Lucille sighed inaudibly. She was a girl with a conscience, and that conscience was troubling her a little. She agreed with Archie that the discovery of the Wigmore Venus in his artistically furnished suite would give Mr. Brewster a surprise. “Surprise,” indeed, was perhaps an inadequate word. She was sorry for her father, but the instinct of self-preservation is stronger than any other emotion.

Archie whistled merrily on the following morning as, having driven a nail into his father-in-law’s wall-paper, he adjusted the cord from which the Wigmore Venus was suspended. He was a kind-hearted young man, and, though Mr. Daniel Brewster had on many occasions treated him with a good deal of austerity, his simple soul was pleased at the thought of doing him a good turn. He had just completed his work and was stepping cautiously down when a voice behind him nearly caused him to overbalance.

“What the devil?”

Archie turned beamingly.

“Hullo, old thing! Many happy returns of the day!”

Mr. Brewster was standing in a frozen attitude.

“What—what—” he gurgled.

Mr. Brewster was not in one of his sunniest moods that morning. The proprietor of a large hotel has many things to disturb him, and to-day things had been going wrong. He had come up to his suite with the idea of restoring his shaken nerve-system with a quiet cigar, and the sight of his son-in-law had, as so frequently happened, made him feel worse than ever. But, when Archie had descended from the chair and moved aside to allow him an uninterrupted view of the picture, Mr. Brewster realized that a worse thing had befallen him than a mere visit from one who always made him feel that the world was a bleak place.

He stared at the Venus dumbly. Unlike most hotel proprietors, Daniel Brewster was a connoisseur of art. Connoisseuring was, in fact, his hobby. Even the public rooms of the Cosmopolis were decorated with taste, and his own private suite was a shrine of all that was best and most artistic. His tastes were quiet and restrained, and it is not too much to say that the Wigmore Venus hit him behind the ear like a stuffed eelskin.

So great was the shock that for some moments it kept him silent, and before he could recover speech, Archie had explained.

“It’s a birthday present from Lucille, don’t you know.”

Mr. Brewster crushed down the breezy speech he had intended to utter.

“Lucille gave me—that?” he muttered.

He swallowed pathetically. He was suffering, but the iron courage of the Brewsters stood him in good stead. This man was no weakling. Presently, the rigidity of his face relaxed. He was himself again. Of all things in the world, he loved his daughter most, and if, in whatever mood of temporary insanity, she had brought herself to suppose that this beastly daub was the sort of thing he would like for a birthday present, he must accept the situation like a man. He would, on the whole, have preferred death to a life lived in the society of the Wigmore Venus, but even that torment must be endured if the alternative was the hurting of Lucille’s feelings.

“I think I’ve chosen a pretty likely spot to hang the thing—what?” said Archie cheerfully. “It looks well alongside those Japanese prints, don’t you think? Sort of stands out.”

Mr. Brewster licked his dry lips and grinned a ghastly grin.

“It does stand out,” he agreed.

Archie was not a man who readily allowed himself to become worried, especially about people who were not in his own immediate circle of friends, but, in the course of the next week, he was bound to admit that he was not altogether easy in his mind about his father-in-law’s mental condition. He had read all sorts of things in the Sunday papers and elsewhere about the constant strain to which captains of industry are subjected, a strain which, sooner or later, is only too apt to make the victim go all blooey, and it seemed to him that Mr. Brewster was beginning to find the going a trifle too tough for his stamina. Undeniably he was behaving in an odd manner, and Archie, though no physician, was aware that when the American business man—that restless, ever-active human machine—starts behaving in an odd manner, the next thing you know is that two strong men, one attached to each arm, are hurrying him into the cab bound for Bloomingdale. He did not confide his misgivings to Lucille, not wishing to cause her anxiety. He hunted up Reggie van Tuyl at the club, and sought advice from him.

“I say, Reggie old thing, present company excepted, have there been any loonies in your family?”

Reggie stirred in the slumber which always gripped him in the early afternoon.

“ ‘Loonies?’ ” he mumbled sleepily. “Rather! My uncle Edgar thought he was twins.”

“ ‘Twins,’ eh?”

“Yes. Silly idea! I mean, you’d have thought one of my uncle Edgar would have been enough for any man.”

“How did the thing start?” asked Archie.

“ ‘Start?’ Well, the first thing we noticed was when he began wanting two of everything. Had to set two places for him at dinner, and so on. Always wanted two seats at the theater. Ran into money, I can tell you.”

“He didn’t behave rummily up till then?”

“Not that I remember. Why?”

Archie’s tone became grave.

“Well, I’ll tell you, old man, though I don’t want it to go any further, that I’m a bit worried about my jolly old father-in-law. I believe he’s about to go in off the deep end. Dashed weird his behavior has been the last few days.”

“Such as?” murmured Mr. van Tuyl.

“Well, the other morning I happened to be in his suite—incidentally he wouldn’t go above ten dollars, and I wanted twenty-five—and he suddenly picked up a whacking big paper-weight and bunged it for all he was worth.”

“At you?”

“Not at me. That was the rummy part of it. At a mosquito on the wall, he said. Well, I mean to say, do chappies bung paper-weights at mosquitoes? I mean, is it done?”

“Smash anything?”

“Curiously enough, no. But he only just missed a rather decent picture which Lucille had given him for his birthday.”

“Sounds queer.”

“And, talking of that picture, I looked in on him about a couple of afternoons later, and he’d taken it down from the wall and laid it on the floor and was staring at it in a dashed marked sort of manner. That was peculiar—what?”

“ ‘On the floor?’ ”

“On the jolly old carpet. When I came in, he was goggling at it in a sort of glassy way. Absolutely rapt, don’t you know. My coming-in gave him a start—seemed to rouse him from a kind of trance, you know—and he jumped like an antelope, and, if I hadn’t happened to grab him, he would have trampled bang on the thing. It was deuced unpleasant, you know. His manner was rummy. He seemed to be brooding on something. What ought I to do about it, do you think? It’s not my affair, of course, but it seems to me that, if he goes on like this, one of these days he’ll be stabbing some one with a pickle-fork.”

To Archie’s relief, his father-in-law’s symptoms showed no signs of development. In fact, his manner reverted to the normal once more, and, a few days later, meeting Archie in the lobby of the hotel, he seemed quite cheerful. It was not often that he wasted his time talking to his son-in-law, but, on this occasion, he chatted with him for several minutes about the big picture-robbery which had formed the chief item of news on the front pages of the morning papers that day. It was Mr. Brewster’s opinion that the outrage had been the work of a gang, and that nobody was safe.

Daniel Brewster had spoken of this matter with a strange earnestness, but his words had slipped from Archie’s mind when he made his way that night to his father-in-law’s suite. Archie was in an exalted mood. In the course of dinner he had had a bit of good news which was occupying his thoughts to the exclusion of all other matters. It had left him in a comfortable, if rather dizzy condition of benevolence to all created things.

He found the door of the Brewster suite unlocked, which at any other time would have struck him as unusual, but to-night he was in no frame of mind to notice these trivialities. He went in, and, finding the room dark and no one at home, sat down, too absorbed in his thoughts to switch on the lights, and gave himself up to dreamy meditation.

There are certain moods in which one loses count of time, and Archie could not have said how long he had been sitting in the deep armchair near the window when he first became aware that he was not alone in the room. He had closed his eyes, the better to meditate, so had not seen anyone enter. Nor had he heard the door open. The first intimation he had that somebody had come in was when some hard substance knocked against some other hard object, producing a sharp sound which brought him back to earth with a jerk.

He sat up silently. The fact that the room was still in darkness made it obvious that something nefarious was afoot. He stared into the blackness, and, as his eyes grew accustomed to it, was presently able to see an indistinct form bending over something on the floor. The sound of rather stertorous breathing came to him.

Archie had many defects which prevented him being the perfect man, but lack of courage was not one of them. His somewhat rudimentary intelligence had occasionally led his superior officers during the war to thank God that Great Britain had a navy; but even these stern critics had found nothing to complain of in the manner in which he bounded over the top. Some of us are thinkers, others men of action. Archie was a man of action, and he was out of his chair and sailing in the direction of the back of the intruder’s neck before a wiser man would have completed his plan of campaign. The miscreant collapsed under him with a squashy sound, like the wind going out of a pair of bellows, and Archie, taking a firm seat on his spine, rubbed the other’s face in the carpet and awaited the progress of events.

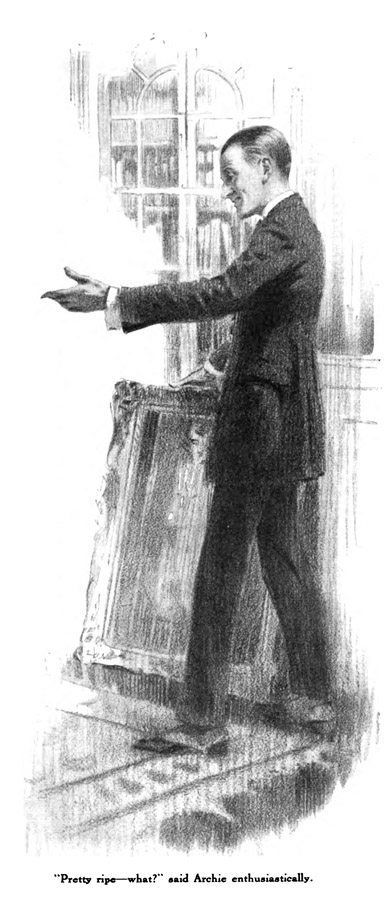

At the end of half a minute, it became apparent that there was going to be no counter-attack. The dashing swiftness of the assault had apparently had the effect of depriving the marauder of his entire stock of breath. He was gurgling to himself in a pained sort of way and making no effort to rise. Archie, feeling that it would be safe to get up and switch on the light, did so, and, turning after completing this maneuver, was greeted by the spectacle of his father-in-law seated on the floor in a breathless and disheveled condition, blinking at the sudden illumination. On the carpet beside Mr. Brewster lay a long knife, and beside the knife lay the handsomely framed masterpiece of J. B. Wheeler’s fiancée, Miss Alice Wigmore. Archie stared at this collection dumbly.

“Oh, what ho!” he observed at length, feebly.

A distinct chill manifested itself in the region of Archie’s spine. This could mean only one thing. His fears had been realized. The strain of modern life, with all its hustle and excitement, had at last proved too much for Mr. Brewster. Crushed by the thousand and one anxieties and worries of a millionaire’s existence, Daniel Brewster had gone off his onion.

Archie was nonplused. This was his first experience of this kind of thing. What, he asked himself, was the proper procedure in a situation of this sort? What was the local rule? Where, in a word, did he go from here? He was still musing in an embarrassed and baffled way, having taken the precaution of kicking the knife under the sofa, when Mr. Brewster spoke. And there was in both the words and the method of their delivery so much of his old familiar self that Archie felt quite relieved.

“So, it’s you—is it?—you wretched blight, you miserable weed!” said Mr. Brewster, having recovered enough breath to go on with. He glowered at his son-in-law despondently. “I might have expected it. If I was at the North Pole, I could count on you butting in.”

“Shall I get you a drink of water?” said Archie.

“What the devil,” demanded Mr. Brewster, “do you imagine I want with a drink of water?”

“Well”—Archie hesitated delicately—“I had a sort of idea that you had been feeling the strain a bit. I mean to say, rush of modern life and all that sort of thing——”

“What are you doing in my room?” said Mr. Brewster, changing the subject.

“Well, I came to tell you something, and I came in here and was waiting for you, and I saw some chappie biffing about in the dark, and I thought it was a burglar or something after some of your things; so, thinking it over, I got the idea that it would be a fairly juicy scheme to land on him with both feet. No idea it was you, old thing. Frightfully sorry and all that. Meant well.”

Mr. Brewster sighed deeply. He was a just man, and he could not but realize that, in the circumstances, Archie had behaved not unnaturally.

“Oh, well,” he said; “I might have known something would go wrong.”

“Awfully sorry!”

“It can’t be helped. What was it you wanted to tell me?” He eyed his son-in-law piercingly. “Not a cent over twenty dollars,” he said coldly.

Archie hastened to dispel the pardonable error.

“Oh, it wasn’t anything like that,” he said. “As a matter of fact, I think it’s a good egg. It has bucked me up to no inconsiderable degree. I was dining with Lucille just now, and, as we dallied with the foodstuffs, she told me something which—well, I’m bound to say it made me feel considerably braced. She told me to trot along and ask if you would mind——”

“I gave Lucille a hundred dollars only last Tuesday.”

Archie was pained.

“Adjust this sordid outlook, old thing,” he urged. “You simply aren’t anywhere near it. Right off the target, absolutely! What Lucille told me to ask you was if you would mind at some tolerably near date being a grandfather. Rotten thing to be, of course,” proceeded Archie commiseratingly, “for a chappie of your age, but there it is!”

Mr. Brewster gulped.

“Do you mean to say——”

“I mean, apt to make a fellow feel a bit of a patriarch. Snowy hair and what-not. And, of course, for a chappie in the prime of life like you——”

“Do you mean to tell me— Is this true?”

“Absolutely! Of course, speaking for myself, I’m all for it. I don’t know when I’ve felt more bucked. I sang as I came up here—absolutely warbled in the elevator. But you——”

A curious change had come over Mr. Brewster. He was one of those men who have the appearance of having been hewn out of the solid rock, but now, in some indescribable way, he seemed to have melted. For a moment, he gazed at Archie, then, moving quickly forward, he grasped his hand in an iron grip.

“This is the best news I’ve ever had!”

“Awfully good of you to take it like this,” said Archie cordially. “I mean, being a grandfather——”

Mr. Brewster smiled. Of a man of his appearance, one could hardly say that he smiled playfully, but there was something in his expression that remotely suggested playfulness.

“My dear old bean—” he said. Archie started. “My dear old bean,” repeated Mr. Brewster firmly, “I’m the happiest man in America!” His eyes fell on the picture which lay on the floor. He gave a slight shudder, but recovered himself immediately. “After this,” he said, “I can reconcile myself to living with that thing for the rest of my life. I feel it doesn’t matter.”

“I say!” said Archie. “How about that? Wouldn’t have brought the thing up if you hadn’t introduced the topic, but, speaking as man to man, what the dickens were you up to when I landed on your spine just now?”

“I suppose you thought I had gone off my head.”

“Well, I’m bound to say——”

Mr. Brewster cast an unfriendly glance at the picture.

“Well, I had every excuse, after living with that infernal thing for a week.”

Archie looked at him, astonished.

“I say, old thing—I don’t know if I have got your meaning exactly, but you somehow give me the impression that you don’t like that jolly old work of art.”

“Like it!” cried Mr. Brewster. “It’s nearly driven me mad. Every time it caught my eye, it gave me a pain in the neck. To-night, I felt as if I couldn’t stand it any longer. I didn’t want to hurt Lucille’s feelings by telling her, so I made up my mind I would cut the damned thing out of its frame and tell her it had been stolen.”

“What an extraordinary thing! Why, that’s exactly what old Wheeler did.”

“Who is old Wheeler?”

“Artist chappie. Pal of mine. His fiancée painted the thing, and, when I lifted it off him, he told her it had been stolen. He didn’t seem frightfully keen on it, either.”

“Your friend Wheeler has evidently good taste.”

Archie was thinking.

“Well, all this rather gets past me,” he said. “Personally, I’ve always admired the thing. Dashed ripe bit of work, I’ve always considered. Still, of course, if you feel that way——”

“You may take it from me that I do.”

“Well then, in that case—you know what a clumsy devil I am—you can tell Lucille it was all my fault——”

The Wigmore Venus smiled up at Archie, it seemed to him, with a pathetic, pleading smile. For a moment, he was conscious of a feeling of guilt; then, closing his eyes, and hardening his heart, he sprang lightly in the air and descended with both feet on the picture. There was a sound of rending canvas, and the Venus ceased to smile.

“Golly!” said Archie, regarding the wreckage remorsefully.

Mr. Brewster did not share his remorse. For the second time that night, he gripped him by the hand.

“My boy!” he quavered. He stared at Archie as if he were seeing him with new eyes. “My dear boy, you were through the war, were you not?”

“Eh? Oh, yes—right through the jolly old war!”

“What was your rank?”

“Oh, second lieutenant.”

“You ought to have been a general!” Mr. Brewster clasped his hand once more in a vigorous embrace. “I only hope,” he added, “that your son will be like you.”

There are certain compliments, or compliments coming from certain sources, before which modesty reels, stunned. Archie’s did. He swallowed convulsively. He had never thought to hear these words from Daniel Brewster.

“How would it be, old thing,” he said, almost brokenly, “if you and I trickled down to the bar and had a spot of sherbet?”

Editor’s note:

Printer’s errors corrected above:

Magazine had ‘wrought’ in “she had brought herself to suppose”

Magazine had “Shall I get you an drink of water?”; corrected to “a”

Magazine had unneeded comma after second ‘compliments’ in next-to-last paragraph.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums