The Saturday Evening Mail: New York, November 30, 1912.

THE PRINCE AND BETTY

By Pelhan G. Wodehouse

ILLUSTRATED BY JOHN V. RANCK

CHAPTER XXII.

(CONTINUED.)

“PEACEFUL MOMENTS,” said Mr. Jarvis. “Sure, dat’s right. A guy comes to me and says he wants you put through it, but I gives him de trundown.”

“So I was informed,” said Smith. “Well, failing you, they went to a gentleman of the name of Reilly——”

“Spider Reilly?”

“Exactly. Spider Reilly, the lessee and manager of the Three Points gang.”

Mr. Jarvis frowned.

“Dose T’ree Points, dey’re to de bad. Dey’re fresh.”

“It is too true, Comrade Jarvis.”

“Say,” went on Mr. Jarvis, waxing wrathful at the recollection, “what do youse t’ink dem fresh stiffs done de odder night? Started some rough house woik in me own dance-joint.”

“Shamrock Hall?” said Smith. “I heard about it.”

“Dat’s right, Shamrock Hall. Got gay, dey did, wit’ some of the Table Hillers. Say, I got it in for dem gazebos, sure I have. Surest t’ing you know.”

Smith beamed approval.

“That,” he said, “is the right spirit. Nothing could be more admirable. We are bound together by our common desire to check the ever-growing spirit of freshness among the members of the Three Points. Add to that the fact that we are united by a sympathetic knowledge of the manners and customs of cats, and especially that Comrade Maude, England’s greatest fancier, is our mutual friend, and what more do we want? Nothing.”

“Mr. Maude’s to de good,” assented Mr. Jarvis, eying John once more in friendly fashion.

“We are all to the good,” said Smith. “Now, the thing I wished to ask you is this: The office of the paper was, until this morning, securely guarded by Comrade Brady, whose name will be familiar to you.”

“De Kid?”

“On the bull’s-eye, as usual. Kid Brady, the coming lightweight champion of the world. Well, he has unfortunately been compelled to leave us, and the way into the office is consequently clear to any sand-bag specialist who cares to wander in. So what I came to ask was, will you take Comrade Brady’s place for a few days?”

“How’s that?”

“Will you come in and sit in the office for the next day or so and help hold the fort? I may mention, that there is money attached to the job. We will pay for your services.”

Mr. Jarvis reflected but a brief moment.

“Why, sure,” he said. “Me fer dat.”

“Excellent, Comrade Jarvis. Nothing could be better. We will see you to-morrow, then. I rather fancy that the gay band of Three Pointers who will undoubtedly visit the offices of Peaceful Moments in the next few days is scheduled to run up against the surprise of their lives.”

“Sure t’ing. I’ll bring me canister.”

“Do,” said Smith. “In certain circumstances one canister is worth a flood of rhetoric. Till to-morrow, then, Comrade Jarvis. I am very much obliged to you.”

“NOT at all a bad hour’s work,” he said, complacently, as they turned out of Groome street. “A vote of thanks to you, John, for your invaluable assistance.”

“I didn’t do much,” said John, with a grin.

“Apparently, no. In reality, yes. Your manner was exactly right. Reserved, yet not haughty. Just what an eminent cat-fancier’s manner should be. I could see that you made a pronounced hit with Comrade Jarvis. By the way, as he is going to show up at the office to-morrow, perhaps it would be as well if you were to look up a few facts bearing on the feline world. There is no knowing what thirst for information a night’s rest may not give Comrade Jarvis. I do not presume to dictate, but if you were to make yourself a thorough master of the subject of catnip it might quite possibly come in useful.”

CHAPTER XXIII.

THE RETIREMENT OF SMITH.

THE first member of the staff of Peaceful Moments to arrive at the office on the following morning was Master Maloney. This sounds like the beginning of a “Plod and Punctuality,” or “How Great Fortunes Have Been Made,” story, but, as a matter of fact, Master Maloney, like Mr. Bat Jarvis, was no early bird. Larks who rose in his neighborhood rose alone. He did not get up with them. He was supposed to be at the office at nine o’clock. It was a point of honor with him, a sort of daily declaration of independence, never to put in an appearance before nine-thirty. On this particular morning he was punctual to the minute, or half an hour late, whichever way you chose to look at it.

He had only whistled a few bars of “My Little Irish Rose,” and had barely got into the first page of his story of life on the prairie, when Kid Brady appeared. The Kid had come to pay a farewell visit. He had not yet begun training, and he was making the best of the short time before such comforts should be forbidden by smoking a big black cigar. Master Maloney eyed him admiringly. The Kid, unknown to that gentleman himself, was Pugsy’s ideal. He came from the plains, and had, indeed, once actually been a cowboy; he was a coming champion; and he could smoke big black cigars. There was no trace of his official well-what-is-it-now? air about Pugsy as he laid down his book and prepared to converse.

“Say, Mr. Smith around anywhere, Pugsy?” asked the Kid.

“Naw, Mr. Brady. He ain’t came yet,” replied Master Maloney, respectfully.

“Late, ain’t he?”

“Sure! He generally blows in before I do.”

“Wonder what’s keepin’ him?”

As he spoke, John appeared. “Hello, Kid,” he said. “Come to say good-by?”

“Yep,” said the Kid. “Seen Mr. Smith around anywhere, Mr. Maude?”

“Hasn’t he come yet? I guess he’ll be here soon. Hello, who’s this?”

A small boy was standing at the door, holding a note.

“Mr. Maude?” he said. “Cop at Jefferson Market give me dis fer you.”

“What!” He took the letter, and gave the boy a dime. “Why, it’s from Smith. Great Scott!”

It was apparent that the Kid was politely endeavoring to veil his curiosity. Master Maloney had no such delicacy.

“What’s in de letter, boss?” he inquired.

“The letter,” said John, slowly, “is from Mr. Smith. And it says that he was sentenced this morning to thirty days on the island for resisting the police.”

“He’s de guy!” admitted Master Maloney, approvingly.

“What’s that?” said the Kid. “Mr. Smith been slugging cops! What’s he been doin’ that for?”

“I must go and find out at once. It beats me.”

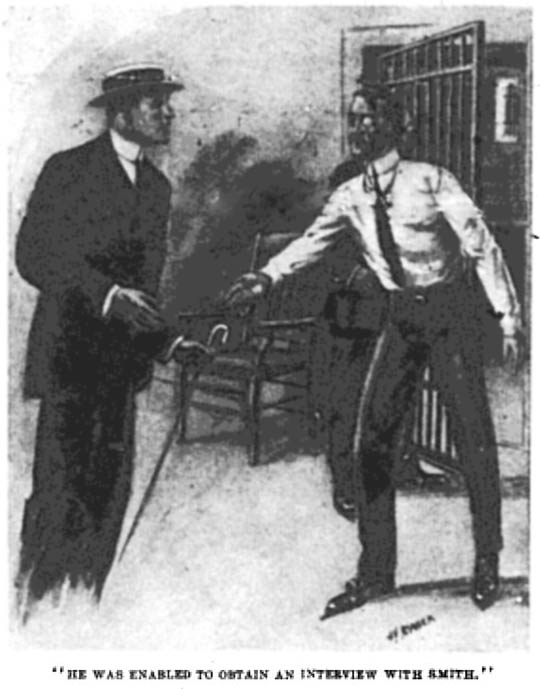

It did not take John long to reach Jefferson Market and by the judicious expenditure of a few dollars he was enabled to obtain an interview with Smith in a back room.

The editor of Peaceful Moments was seated on a bench, looking remarkably disheveled. There was a bruise on his forehead, just where the hair began. He was, however, cheerful. “Ah, John,” he said. “You got my note all right, then?” John looked at him, concerned.

“What on earth does it all mean?”

Smith heaved a regretful sigh.

“I FEAR,” he said, “I have made precisely the blamed fool of myself that Comrade Parker hoped I would.”

“Parker!”

Smith nodded.

“I may be misjudging him, but I seem to see the hand of Comrade Parker in this. We had a raid at my house last night, John. We were pulled.”

“What on earth——”

“Somebody—if it was not Comrade Parker it was some other citizen dripping with public spirit—tipped the police off that certain sports were running a poolroom in the house where I live.”

On his departure from the News, Smith, from motives of economy, had moved from his hotel in Washington square and taken a furnished room on Fourteenth street.

“There actually was a poolroom there,” he went on, “so possibly I am wronging Comrade Parker in thinking that this was a scheme of his for getting me out of the way. At any rate, somebody gave the tip, and at about three o’clock this morning I was aroused from a dreamless slumber by quite a considerable hammering at my door. There, standing on the mat, were two policemen. Very cordially the honest fellows invited me to go with them. A conveyance, it seemed, waited in the street without. I disclaimed all connection with the bad gambling persons below, but they replied that they were cleaning up the house, and, if I wished to make any remarks, I had better make them to the magistrate. This seemed reasonable. I said I would put on some clothes and come along. They demurred. They said they couldn’t wait about while I put on clothes. I pointed out that sky-blue pajamas with old-rose frogs were not the costume in which the editor of a great New York weekly paper should be seen abroad in one of the world’s greatest cities, but they assured me—more by their manner than their words—that my misgivings were groundless, so I yielded. These men, I told myself, have lived longer in New York than I. They know what is done, and what is not done. I will bow to their views. So I was starting to go with them like a lamb, when one of them gave me a shove in the ribs with his nightstick. And it was here that I fancy I may have committed a slight error of policy.”

He smiled dreamily for a moment, then went on.

“I admit that the old Berserk blood of the Smiths boiled at that juncture. I picked up a sleep-producer from the floor, as Comrade Brady would say, and handed it to the big-stick merchant. He went down like a sack of coal over the bookcase, and at that moment I rather fancy the other gentleman must have got busy with his club. At any rate, somebody suddenly loosed off some fifty thousand dollars’ worth of fireworks, and the next thing I knew was that the curtain had risen for the next act on me, discovered sitting in a prison cell, with an out-size in lumps on my forehead.”

He sighed again.

“What ‘Peaceful Moments’ really needs,” he said, “is a sitz-redacteur. A sitz-redacteur, John, is a gentleman employed by German newspapers with a taste for lese-majeste to go to prison whenever required in place of the real editor. The real editor hints in his bright and snappy editorial, for instance, that the Kaiser’s mustache gives him bad dreams. The police force swoops down in a body on the office of the journal and are met by the sitz-redacteur, who goes with them cheerfully, allowing the editor to remain and sketch out plans for his next week’s article on the Crown Prince. We need a sitz-redacteur on ‘Peaceful Moments’ almost as much as a fighting editor. Not now, of course. This has finished the thing. You’ll have to close down the paper now.”

“Close it down!” cried John. “You bet I won’t.”

“MY dear old son!” said Smith seriously, “what earthly reason have you for going on with it? You only came in to help me, and I am no more. I am gone like some beautiful flower that withers in the night. Where’s the sense of getting yourself beaten up then? Quit!”

John shook his head.

“I wouldn’t quit now if you paid me.”

“But——” A policeman appeared.

“Say, pal,” he remarked to John, “you’ll have to be fading away soon, I guess. Give you three minutes more. Say it quick.”

He retired. Smith looked at John.

“You won’t quit?” he said.

“No.” Smith smiled.

“You’re an all-wool sport, John,” he said. “I don’t suppose you know how to spell quit. Well, then, if you are determined to stand by the ship like Comrade Casabianca, I’ll tell you an idea that came to me in the watches of the night. If ever you want to get ideas, John, you spend a night in one of these cells. They flock to you. I suppose I did more profound thinking last night than I’ve ever done in my life. Well, here’s the idea. Act on it or not, as you please. I was thinking over the whole business from soup to nuts, and it struck me that the queerest part of it all is that whoever owns these Broster street tenements should care a Canadian dime whether we find out who he is or not.”

“Well, there’s the publicity,” began John.

“Tush!” said Smith. “And possibly bah! Do you suppose that the sort of man who runs Broster street is likely to care a darn about publicity? What does it matter to him if the papers soak it to him for about two days? He knows they’ll drop him and go on to something else on the third, and he knows he’s broken no law. No, there’s something more in this business than that. Don’t think that this bright boy wants to hush us up simply because he is a sensitive plant who can’t bear to think that people should be cross with him. He has got some private reason for wanting to lie low.”

“Well, but what difference——?”

“Comrade, I’ll tell you. It makes this difference: that the rents are almost certainly collected by some confidential person belonging to his own crowd, not by an ordinary collector. In other words, the collector knows the name of the man he’s collecting for. But for this little misfortune of mine, I was going to suggest that we waylay that collector, administer the third degree and ask him who his boss is.”

John uttered an exclamation.

“You’re right! I’ll do it.”

“You think you can? Alone?”

“Sure! Don’t you worry. I’ll——”

THE door opened and the policeman reappeared.

“Time’s up. Slide, sonny.”

John said good-by to Smith and went out. He had a last glimpse of his late editor, a sad smile on his face, telling the policeman what was apparently a humorous story. Complete goodwill seemed to exist between them. John consoled himself as he went away with the reflection that Smith’s was a temperament that would probably find a bright side even to a thirty-days’ visit to Blackwell’s Island.

He walked thoughtfully back to the office. There was something lonely, and yet wonderfully exhilarating, in the realization that he was now alone and in sole charge of the campaign. It braced him. For the first time in several weeks he felt positively light-hearted.

CHAPTER XXIV.

THE CAMPAIGN QUICKENS.

MR. JARVIS was as good as his word. Early in the afternoon he made his appearance at the office of “Peaceful Moments,” his forelock more than usually well oiled in honor of the occasion, and his right coat pocket bulging in a manner that betrayed to the initiated eye the presence of his trusty “canister.” With him, in addition, he brought a long, thin young man who wore under his brown tweed coat a blue-and-red striped sweater. Whether he brought him as an ally in case of need or merely as a kindred soul with whom he might commune during his vigil, did not appear.

Pugsy, startled out of his wonted calm by the arrival of this distinguished company, gazed after the pair as they passed into the inner office, with protruding eyes.

John greeted the allies warmly, and explained Smith’s absence. Mr. Jarvis listened to the story with interest and introduced his colleague.

“T’ought I’d let him chase along. Long Otto’s his monaker.”

“Sure!” said John. “The more the merrier. Take a seat. You’ll find cigars over there. You won’t mind my not talking for the moment? There’s a wad of work to clear up.”

This was an overstatement. He was comparatively free of work, press day having only just gone by; but he was keenly anxious to avoid conversation on the subject of cats, of his ignorance of which Mr. Jarvis’s appearance had suddenly reminded him. He took up an old proof sheet and began to glance through it, frowning thoughtfully.

Mr. Jarvis regarded the paraphernalia of literature on the table with interest. So did Long Otto, who, however, being a man of silent habit, made no comment. Throughout the seance and the events which followed it he confined himself to an occasional grunt. He seemed to lack other modes of expression.

“Is dis where youse writes up pieces fer de poiper?” inquired Mr. Jarvis.

“This is the spot,” said John. “On busy mornings you could hear our brains buzzing in Madison Square Garden. Oh, one moment.”

He rose and went into the outer office.

“Pugsy,” he said, “do you know Broster street?”

“Sure.”

“Could you find out for me exactly when the man comes round collecting for rents?”

“Surest t’ing you know. I know a kid what knows anodder kid what lives dere.”

“Then go and do it now. And after you’ve found out you can take the rest of the day off.”

“Me fer dat,” said Master Maloney, with enthusiasm. “I’ll take me goil to de Bronx Zoo.”

“Your girl? I didn’t know you’d got a girl, Pugsy. I always imagined you as one of those strong, stern, blood-and-iron men who despised girls. Who is she?”

“AW, she’s a kid,” said Pugsy. “Her pa runs a delicatessen shop down our street. She ain’t a bad mutt,” added the ardent swain. “I’m her steady.”

“Well, mind you send me a card for the wedding. And if two dollars would be a help——”

“Sure t’ing. T’anks, boss. You’re all right.”

It had occurred to John that the less time Pugsy spent in the outer office during the next few days, the better. The lull in the warfare could not last much longer, and at any moment a visit from Spider Reilly and his adherents might be expected. Their probable first move in such an event would be to knock Master Maloney on the head to prevent his giving warning of their approach.

Events proved that he had not been mistaken. He had not been back in the inner office for more than a quarter of an hour when there came from without the sound of stealthy movements. The handle of the door began to revolve slowly and quietly. The next moment three figures tumbled into the room.

It was evident that they had not expected to find the door unlocked, and the absence of resistance when they applied their weight had surprising effects. Two of the three did not pause in their career till they cannoned against the table. The third checked himself by holding the handle.

John got up coolly.

“Come right in,” he said. “What can we do for you?” It had been too dark on the other occasion of his meeting with the Three Pointers to take note of their faces, though he fancied that he had seen the man holding the door-handle before. The others were strangers. They were all exceedingly unprepossessing in appearance.

There was a pause. The three marauders had become aware of the presence of Mr. Jarvis and his colleague, and the meeting was causing them embarrassment, which may have been due in part to the fact that both had produced and were toying meditatively with ugly-looking pistols.

Mr. Jarvis spoke.

“Well,” he said, “what’s doin’?”

The man to whom the question was directly addressed appeared to have some difficulty in finding a reply. He shuffled his feet and looked at the floor. His two companions seemed equally at a loss.

“Goin’ to start anyt’ing?” inquired Mr. Jarvis, casually.

The humor of the situation suddenly tickled John. The embarrassment of the uninvited guests was ludicrous.

“You’ve just dropped in for a quiet chat, is that it?” he said. “Well, we’re all delighted to see you. The cigars are on the table. Draw up your chairs.”

Mr. Jarvis opposed the motion. He drew slow circles in the air with his revolver.

“Say! Youse had best beat it. See?”

Long Otto grunted sympathy with the advice.

“And youse had best go back to Spider Reilly,” continued Mr. Jarvis, “and tell him there ain’t nothin’ goin’ in the way of rough-house wit’ dis gent here. And you can tell de Spider,” went on Bat, with growing ferocity, “dat next time he gits fresh and starts in to shootin’ up my dance-joint, I’ll bite de head off’n him. See? Dat goes. If he t’inks his little two-by-four crowd can git away wit’ de Groome street, he’s got anodder guess comin’. An’ don’t fergit dis gent here and me is friends, and anyone dat starts anyt’ing wit’ dis gent is going to find trouble. Does dat go? Beat it.”

He jerked his shoulder in the direction of the door.

The delegation then withdrew.

“Thanks,” said John. “I’m much obliged to you both. You’re certainly there with the goods as fighting editors. I don’t know what I should have done without you.”

“Aw, Chee!” said Mr. Jarvis, handsomely dismissing the matter. Long Otto kicked the leg of a table and grunted.

PUGSY MALONEY’S report on the following morning was entirely satisfactory. Rents were collected in Broster street on Thursdays. Nothing could have been more convenient, for that very day happened to be Thursday.

“I rubbered around,” said Pugsy, “an’ done de sleut’ act, an’ it’s this way: Dere’s a feller blows in every T’ursday ‘bout six o’clock, an’ den it’s up to de folks to dig down inter deir jeans for de stuff, or out dey goes before supper. I got dat from my kid frien’ what knows a kid what lives dere. An’ say, he has it pretty fierce, dat kid. De kid what lives dere. He’s a wop kid, an Italian, an’ he’s in bad, ’cos his pa comes over from Italy to woik on de subway.”

“I don’t see why that puts him in bad,” said John, wonderingly. “You don’t construct your stories well, Pugsy. You start at the end, then go back to any part which happens to appeal to you at the moment, and eventually wind up at the beginning. Why is this kid in bad because his father has come to work on the subway?”

“Why, sure, because his pa got fired an’ swatted de foreman one on de coco, an’ dey gives him t’oity days. So de kid’s all alone, an’ no one to pay de rent.”

“I see,” said John. “Well, come along with me and introduce me, and I’ll look after that.”

At half-past five John closed the office for the day, and, armed with a big stick and conducted by Master Maloney, made his way to Broster street. To reach it, it was necessary to pass through a section of the enemy’s country, but the perilous passage was safely negotiated. The expedition reached its unsavory goal intact.

The wop kid inhabited a small room at the very top of a building half-way down the street. He was out when John and Pugsy arrived.

It was not an abode of luxury, the tenement; they had to feel their way up the stairs in almost pitch darkness. Most of the doors were shut, but one on the second floor was ajar. Through the opening John had a glimpse of a number of women sitting on up-turned boxes. The floor was covered with little heaps of linen. All the women were sewing. Stumbling in the darkness, John almost fell against the door.

None of the women looked up at the noise. In Broster street time was evidently money.

On the top floor Pugsy halted before the open door of an empty room. The architect in this case had apparently given rein to a passion for originality, for he had constructed the apartment without a window of any sort whatsoever. The entire stock of air used by the occupants came through a small opening over the door.

It was a warm day and John recoiled hastily.

“Is this the kid’s room?” he said. “I guess the corridor’s good enough for me to wait in. What the owner of this place wants,” he went on reflectively, “is scalping. Well, we’ll do it in the paper if we can’t in any other way. Is this your kid?”

Text variant, unresolved:

In Ch. XIV, Jarvis’s phrase “If he t’inks his little two-by-four crowd can git away wit’ de Groome street” appears this way only here. In the American book edition the wording is “git way wit’ ”; in the Captain serial and later book of Psmith, Journalist it is “put it across”. Ian Michaud wonders if this was intended to be “git gay with” as used elsewhere in this story.

Text from American book edition omitted from this serial:

In Ch. XXIII, after “A policeman appeared” the book version continues “at the door.”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums