Liberty, June 16, 1928

THE picturesque village of Rudge-in-the-Vale dozed in the summer sunshine. Along its narrow High Street the only signs of life visible were a cat stropping its backbone against the Jubilee Watering Trough, some flies doing deep-breathing exercises on the hot windowsills, and a little group of serious thinkers who, propped up against the wall of the Carmody Arms, were waiting for that establishment to open.

At no time is there ever much doing in Rudge’s main thoroughfare, but the hour at which a stranger entering it is least likely to suffer the illusion that he has strayed into Broadway, Piccadilly, or the Rue de Rivoli is at 2 o’clock on a warm afternoon in July.

You will find Rudge-in-the-Vale, if you search carefully, in that pleasant section of rural England where the gray stone of Gloucestershire gives place to Worcestershire’s old red brick.

Quiet—in fact, almost unconscious—it nestles beside the tiny river Skirme and lets the world go by, somnolently content with its Norman church, its eleven public houses, its pop.—to quote the Automobile Guide—of 3,541, and its only effort in the direction of modern progress, the emporium of Chas. Bywater, Chemist.

Chas. Bywater is a live wire. He takes no afternoon siesta, but works while others sleep. Rudge as a whole is inclined, after luncheon, to go into the back room, put a handkerchief over its face, and take things easy for a bit. But not Chas. Bywater.

At the moment when this story begins, he was all bustle and activity and had just finished selling to Colonel Meredith Wyvern a bottle of Brophy’s Paramount Elixir (said to be good for gnat bites).

Having concluded his purchase, Colonel Wyvern would have preferred to leave. But Mr. Bywater was a man who liked to sweeten trade with pleasant conversation. Moreover, this was the first time the Colonel had been inside his shop since that sensational affair up at the Hall two weeks ago; and Chas. Bywater, who held the unofficial position of chief gossip monger to the village, was aching to get to the bottom of that.

With the bare outline of the story he was, of course, familiar. Rudge Hall, seat of the Carmody family for so many generations, contained in its fine old park a number of trees which had been planted somewhere about the reign of Queen Elizabeth. This meant that every now and then one of them would be found to have become a wabbly menace to the passer-by, so that experts had to be sent for to reduce it, with a charge of dynamite, to a harmless stump.

Well, two weeks before, it seemed, they had blown up one of the Hall’s Elizabethan oaks, and as near as a toucher, Rudge learned, had blown up Colonel Wyvern and Mr. Carmody with it. The two friends had come walking by just as the experts set fire to the train, and had had a very narrow escape.

Thus far the story was common property in the village, and had been discussed nightly in the eleven taprooms of its eleven public houses. But Chas. Bywater, with his trained nose for news and that sixth sense which had so often enabled him to ferret out the story behind the story when things happened in the upper world of the nobility and gentry, could not help feeling that there was more in it than this. He decided to give his customer the opportunity of confiding in him.

“Warm day, Colonel,” he observed.

“Ur,” grunted Colonel Wyvern.

“Glass going up, I see.”

“Ur.”

“May be in for a spell of fine weather at last.”

“Ur.”

“Glad to see you looking so well, Colonel, after your little accident,” said Chas. Bywater, coming out into the open.

It had been Colonel Wyvern’s intention, for he was a man of testy habit, to inquire of Mr. Bywater why the devil he couldn’t wrap a bottle of Brophy’s Elixir in brown paper and put a bit of string round it without taking the whole afternoon over the task. But at these words he abandoned this project.

Turning a bright mauve and allowing his luxuriant eyebrows to meet across the top of his nose, he subjected the other to a fearful glare.

Turning a bright mauve and allowing his luxuriant eyebrows to meet across the top of his nose, he subjected the other to a fearful glare.

“Little accident?” he said. “Little accident?”

“I was alluding—”

“Little accident!”

“I merely—”

“If by ‘little accident,’ ” said Colonel Wyvern in a thick, throaty voice, “you mean my miraculous escape from death when that fat thug up at the Hall did his very best to murder me, I should be obliged if you would choose your expressions more carefully. Little accident! Good God!”

FEW things in this world are more painful than the realization that an estrangement has occurred between two old friends who for years have jogged amiably along together through life, sharing each other’s joys and sorrows and holding the same views on religion, politics, cigars, wine, and the decadence of the younger generation; and Mr. Bywater’s reaction, on hearing Colonel Wyvern describe Mr. Lester Carmody of Rudge Hall, until two short weeks ago his closest crony, as a fat thug, should have been one of sober sadness.

Such, however, was not the case. Rather was he filled with an unholy exultation. All along he had maintained that there was more in that Hall business than had become officially known, and he stood there with his ears flapping, waiting for details.

These followed immediately and in great profusion; and Mr. Bywater, as he drank them in, began to realize that his companion had certain solid grounds for feeling a little annoyed.

For when, as Colonel Wyvern very sensibly argued, you have been a man’s friend for twenty years, and are walking with him in his park and hear warning shouts and look up and realize that a charge of dynamite is shortly about to go off in your immediate neighborhood, you expect a man who is a man to be a man.

You do not expect him to grab you round the waist and thrust you swiftly in between himself and the point of danger, so that, when the explosion takes place, you get the full force of it and he escapes without so much as a singed eyebrow.

“Quite,” said Mr. Bywater, hitching up his ears another inch.

Colonel Wyvern continued. Whether, if in a condition to give the matter careful thought, he would have selected Chas. Bywater as a confidant, one cannot say. But he was not in such a condition. The stoppered bottle does not care whose is the hand that removes its cork—all it wants is the chance to fizz; and Colonel Wyvern resembled such a bottle.

Owing to the absence from home of his daughter Patricia, he had had no one handy to act as audience for his grievances; and for two weeks he had been suffering torments. He told Chas. Bywater all.

It was a very vivid picture that he conjured up. Mr. Bywater could see the whole thing as clearly as if he had been present in person—from the blasting gang’s first horrified realization that human beings had wandered into the danger zone, to the almost tenser moment when, running up to sort out the tangled heap on the ground, they had observed Colonel Wyvern rise from his seat on Mr. Carmody’s face and had heard him start to tell that gentleman precisely what he thought of him.

Privately, Mr. Bywater considered that Mr. Carmody had acted with extraordinary presence of mind and had given the lie to the theory, held by certain critics, that the landed gentry of England are deficient in intelligence. But his sympathies were, of course, with the injured man.

He felt that Colonel Wyvern had been hardly treated and was quite right to be indignant about it. As to whether the other was justified in alluding to his former friend as a jelly-bellied hell hound, that was a matter for his own conscience to decide.

“I’m suing him,” concluded Colonel Wyvern, regarding an advertisement of Pringle’s Pink Pills with a smoldering eye.

“Quite.”

“The only thing in the world that superfatted old Black Hander cares for is money, and I’ll have his last penny out of him if I have to take the case to the House of Lords.”

“Quite,” said Mr. Bywater.

“I might have been killed. It was a miracle I wasn’t. Five thousand pounds is the lowest figure any conscientious jury could put the damages at. And, if there were any justice in England, they’d ship the scoundrel off to pick oakum in a prison cell.”

Mr. Bywater made noncommittal noises. Both parties to this unfortunate affair were steady customers of his, and he did not wish to alienate either by taking sides. He hoped the Colonel was not going to ask him for his opinion of the rights of the case.

Colonel Wyvern did not. Having relieved himself with some six minutes of continuous speech, he seemed to have become aware that he had bestowed his confidences a little injudiciously. He coughed and changed the subject.

“Where’s that stuff?” he said. “Good God! Isn’t it ready yet? Why does it take you fellows three hours to tie a knot in a piece of string?”

“Quite ready, Colonel,” said Chas. Bywater hastily. “Here it is. I have put a little loop for the finger, to facilitate carrying.”

“Is this stuff really any good?”

“Said to be excellent, Colonel. Thank you, Colonel. Much obliged, Colonel. Good day, Colonel.”

Still fermenting at the recollection of his wrongs, Colonel Wyvern strode to the door and, pushing it open with extreme violence, left the shop.

The next moment the peace of the drowsy summer afternoon was shattered by a hideous uproar. Much of this consisted of a high, passionate barking, the remainder being contributed by the voice of a retired military man raised in anger.

Chas. Bywater blenched, and, reaching out a hand toward an upper shelf, brought down, in the order named, a bundle of lint, a bottle of arnica, and one of the half-crown (or large) size pots of Sooth-o, the recognized specific for cuts, burns, scratches, nettle stings, and dog bites. He believed in preparedness.

II

WHILE Colonel Wyvern had been pouring his troubles into the twitching ear of Chas. Bywater, there had entered the High Street a young man in golf clothes and an Old Rugbeian tie. This was John Carroll, nephew of Mr. Carmody of the Hall. He had walked down to the village, accompanied by his dog Emily, to buy tobacco: and his objective, therefore, was the same many-sided establishment which was supplying the Colonel with Brophy’s Elixir.

For do not be deceived by that “Chemist” after Mr. Bywater’s name. It is mere modesty. Some whim leads this great man to describe himself as a chemist, but in reality he goes much deeper than that. Chas. is the Marshall Field of Rudge, and deals in everything, from crystal sets to mousetraps.

There are several places in the village where you can get stuff they call tobacco, but it cannot be considered in the light of pipe joy for the discriminating smoker. To obtain something that will leave a little skin on the roof of the mouth you must go to Mr. Bywater.

John came up the High Street with slow, meditative strides—a large and muscular young man whose pleasant features betrayed at the moment an inward gloom. What with being hopelessly in love, and one thing and another, his soul was in rather a bruised condition these days; and he found himself deriving from the afternoon placidity of Rudge-in-the-Vale a certain balm and consolation. He had sunk into a dreamy trance, when he was abruptly aroused by the horrible noise which had so shaken Chas. Bywater.

The causes which had brought about this disturbance were simple and are easily explained. It was the custom of the dog Emily, on the occasions when John brought her to Rudge to help him buy tobacco, to yield to an uncontrollable eagerness and gallop on ahead to Mr. Bywater’s shop—where, with her nose wedged against the door, she would stand, sniffing emotionally, till somebody came and opened it.

She had a morbid passion for cough drops, and experience had taught her that by sitting and ogling Mr. Bywater with her liquid amber eyes she could generally secure two or three.

Today, hurrying on as usual, she had just reached the door and begun to sniff when it suddenly opened and hit her sharply on the nose; and, as she shot back with a yelp of agony, out came Colonel Wyvern carrying his bottle of Brophy.

There is an etiquette in these matters on which all right-minded dogs insist. When people trod on Emily, she expected them immediately to fuss over her; and the same procedure seemed to her to be in order when they hit her on the nose with doors.

Waiting expectantly, therefore, for Colonel Wyvern to do the square thing, she was stunned to find that he apparently had no intention of even apologizing. He was brushing past without a word, and all the woman in Emily rose in revolt against such boorishness.

“Just a minute!” she said dangerously. “Just one minute, if you please. Not so fast, my good man. A word with you, if I may trespass upon your valuable time.”

The Colonel, chafing beneath the weight of his wrongs, perceived that they had been added to by a beast of a hairy dog that stood and yapped at him.

“Get out!” he bellowed.

Emily became hysterical.

“Indeed?” she said shrilly. “And who do you think you are, you poor clumsy robot? You come hitting ladies on the nose as if you were the King of England, and, as if that wasn’t enough—”

“Go away, sir!”

“Who the devil are you calling ‘sir’?” Emily had the twentieth century girl’s freedom of speech and breadth of vocabulary. “It’s people like you that cause all this modern unrest and industrial strife. I know your sort well. Robbers and oppressors! And let me tell you another thing—”

At this point the Colonel very injudiciously aimed a kick at Emily.

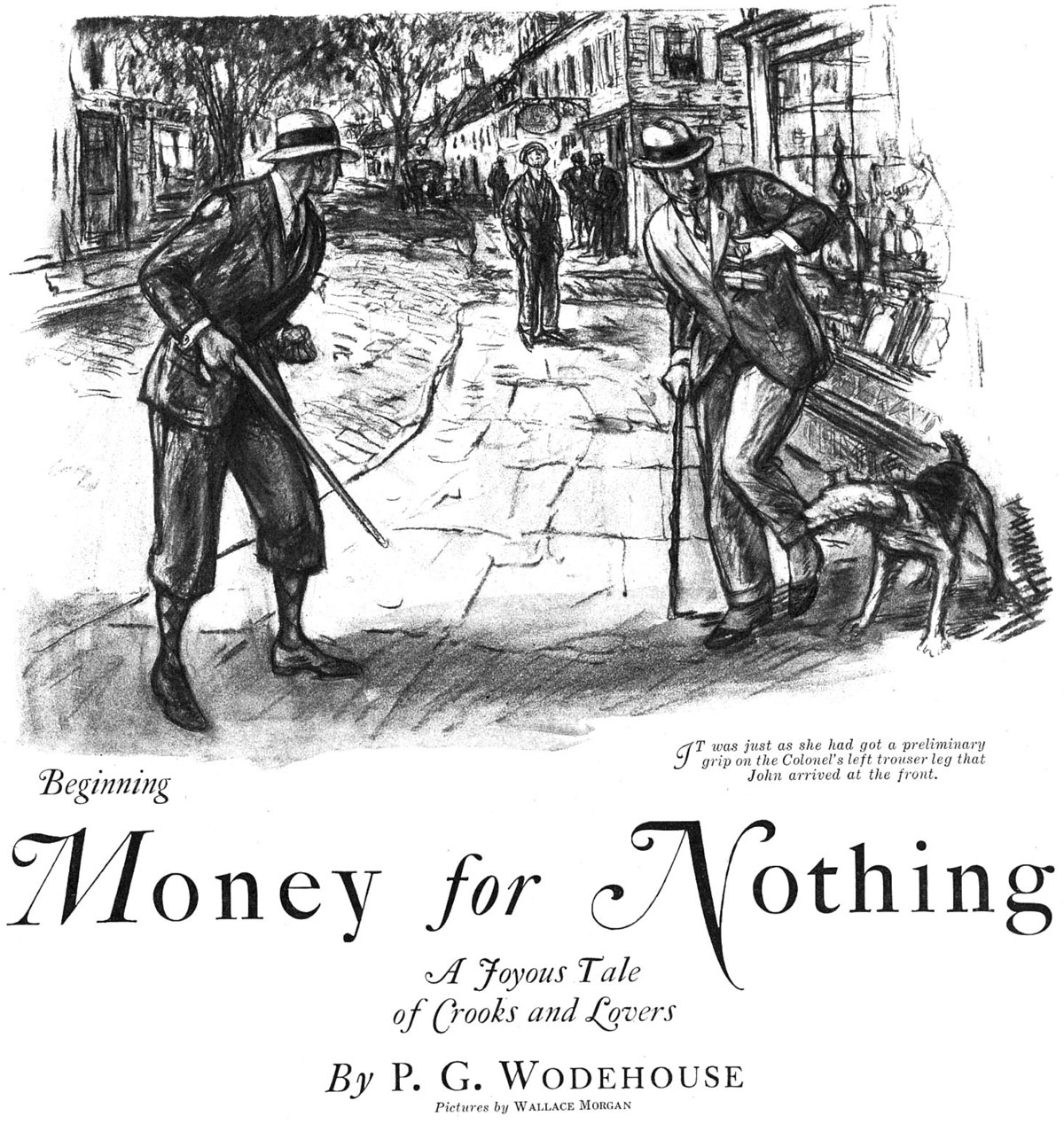

IT was not much of a kick, and it came nowhere near her, but it sufficed. Realizing the futility of words, Emily decided on action. And it was just as she had got a preliminary grip on the Colonel’s left trouser leg that John arrived at the front.

“Emily!” roared John, shocked to the core of his being.

He had excellent lungs, and he used them to the last ounce of their power. A young man who sees the father of the girl he loves being swallowed alive by a Welsh terrier does not spare his voice. The word came out of him like the note of the last trump. And Colonel Wyvern, leaping spasmodically, dropped his bottle of Brophy.

It fell on the pavement and exploded. And Emily, who could do her bit in a rough-and-tumble, but barred bombs, tucked her tail between her legs and vanished. A faint, sleepy cheering from outside the Carmody Arms announced that she had passed that “home from home” and was going well.

John continued to be agitated. You would not have supposed, to look at Colonel Wyvern, that he could have had an attractive daughter; but such was the case, and John’s manner was as concerned and ingratiating as that of most young men in the presence of the fathers of attractive daughters.

“I’m so sorry, Colonel! I do hope you’re not hurt, Colonel.”

The injured man, maintaining an icy silence, raked him with an eye before which sergeant majors had once drooped like withered roses, and walked into the shop. The anxious face of Chas. Bywater loomed up over the counter. John hovered in the background.

“I want another bottle of that stuff,” said the Colonel shortly.

“I’m awfully sorry,” said John.

“I dropped the other outside. I was attacked by a savage dog.”

“I’m frightfully sorry.”

“People ought not to have these pests running loose and not under proper control.”

“I’m fearfully sorry.”

“A menace to the community and a nuisance to everybody,” said Colonel Wyvern.

“Quite,” said Mr. Bywater.

CONVERSATION languished. Chas. Bywater, realizing that this was no moment for lingering lovingly over brown paper and toying dreamily with string, lowered the record for wrapping a bottle of Brophy’s Paramount Elixir.

Colonel Wyvern snatched it and stalked out. And John, who had opened the door for him and had not been thanked, tottered back to the counter and in a low voice expressed a wish for two ounces of the Special Mixture.

“Quite,” said Mr. Bywater. “In one moment, Mr. John.”

With the passing of Colonel Wyvern a cloud seemed to have rolled away from the chemist’s world. He was his old, charmingly chatty self again. He gave John his tobacco, and, detaining him by the simple means of not handing over his change, surrendered himself to the joys of conversation.

“The Colonel appears a little upset, sir.”

“Have you got my change?” said John.

“It seems to me he hasn’t been the same man since that unfortunate episode up at the Hall. Not at all the same sunny gentleman.”

“Have you got my change?”

“A very unfortunate episode, that,” sighed Mr. Bywater.

“My change?”

“I could see, the moment he walked in here, that he was not himself. Shaken. Something in the way he looked at one. I said to myself, ’The Colonel’s shaken!’ ”

John, who had had such recent experience of the way Colonel Wyvern looked at one, agreed. He then asked if he might have his change.

“No doubt he misses Miss Wyvern,” said Chas. Bywater, ignoring the request with an indulgent smile. “When a man’s had a shock like the Colonel’s had—when he’s shaken, if you understand what I mean—he likes to have his loved ones around him. Stands to reason,” said Mr. Bywater.

John had been anxious to leave, but he was so constituted that he could not tear himself away from anyone who had touched on the subject of Patricia Wyvern. He edged a little nearer the counter.

“Well, she’ll be home again soon,” said Chas. Bywater. “Tomorrow, I understand.”

A powerful current of electricity seemed to pass through John’s body. Pat Wyvern had been away so long that he had fallen into a sort of dull apathy in which he wondered sometimes if he would ever see her again.

“What?”

“Yes, sir. She returned from France yesterday. She had a good crossing. She is at the Lincoln Hotel, Curzon Street, London. She thinks of taking the three o’clock train tomorrow. She is in excellent health.”

It did not occur to John to question the accuracy of the other’s information, nor to be surprised at its minuteness of detail. Mr. Bywater, he was aware, had a daughter in the post office.

“Tomorrow!” he gasped.

“Yes, sir. Tomorrow.”

“Give me my change,” said John.

He yearned to be off. He wanted air and space in which he could ponder over this wonderful news.

“No doubt,” said Mr. Bywater, “she—”

“Give me my change!” said John.

Chas. Bywater, happening to catch his eye, did so.

III

TO reach Rudge Hall from the door of Chas. Bywater’s shop, you go up the High Street, turn sharp to the left down River Lane, cross the stone bridge that spans the slow flowing Skirme as it potters past on its way to join the Severn, carry on along the road till you come to the gates of Colonel Wyvern’s nice little house, and then climb a stile and take to the fields. And presently you are in the park and can see through the trees the tall chimneys and red walls of the ancient home of the Carmodys. The scene, when they are not touching off dynamite there under the noses of retired military officers, is one of quiet peace. For John it had always held a peculiar magic.

In the fourteen years which had passed since the Wyverns had first come to settle in Rudge, Pat had contrived, so far as he was concerned, to impress her personality ineffaceably on the landscape. Almost every inch of it was in some way associated with her. Stumps on which she had sat and swung her brown-stockinged legs; trees beneath which she had taken shelter with him from summer storms; gates on which she had climbed, fields across which she had raced, and thorny bushes which she had urged him to penetrate in search of birds’ eggs—they met his eye on every side. The very air seemed to be alive with her laughter. And not even the recollection that that laughter had generally been directed at himself was able to diminish, for John, the glamour of this mile of fairyland.

Halfway across the park, Emily rejoined him with a defensive where-on-earth-did-you-disappear-to manner, and they moved on in company till they rounded the corner of the house and came to the stable yard.

John had a couple of rooms over the stables, and thither he made his way, leaving Emily to fuss round Bolt, the chauffeur, who was washing the Dex-Mayo.

Arrived in his sitting room, he sank into a deck chair and filled his pipe with Mr. Bywater’s Special Mixture. Then, putting his feet up on the table, he stared hard and earnestly at the photograph of Pat which stood on the mantelpiece.

It was a pretty face that he was looking at—one whose charm not even a fashionable modern photographer, of the type that prefers to depict his sitters in a gray fog with most of their features hidden from view, could altogether obscure. In the eyes, a little slanting, there was a Pucklike look, and the curving lips hinted demurely at amusing secrets. The nose had that appealing yet provocative air which slight tiptiltedness gives. It seemed to challenge and at the same time to withdraw.

This was the latest of the Pat photographs, and she had given it to him three months ago, just before she left to go and stay with friends at Le Touquet. And now she was coming home.

John Carroll was one of these solid persons who do not waver in their loyalties. He had always been in love with Pat, and he always would be, though he would have had to admit that she gave him very little encouragement.

There had been a period when, he being fifteen and she ten, Pat had lavished on him all the worship of a small girl for a big boy who can wiggle his ears and is not afraid of cows. But since then her attitude had changed. Her manner toward him nowadays alternated between that of a nurse toward a child who is not quite right in the head and that of the owner of a clumsy but rather likable dog.

Nevertheless, he loved her. And she was coming home!

John sat up suddenly. He was a slow thinker, and only now did it occur to him that with this infernal feud going on between his Uncle Lester and the old Colonel, she would probably look on him as in the enemy’s camp and refuse to see or speak to him.

The thought chilled him to the marrow. Something, he felt, must be done—and swiftly.

He must go up to London this afternoon, tell her the facts, and throw himself on her clemency. If he could convince her that he was wholeheartedly pro-Colonel and regarded his Uncle Lester as the logical successor to Dr. Crippen and the brides-in-the-bath murderer, things might straighten themselves.

Once the brain gets working, there is no knowing where it will stop. The very next instant there had come to John Carroll a thought so new and breath taking that he uttered an audible gasp.

Why shouldn’t he ask Pat to marry him?

JOHN sat tingling from head to foot. The scales seemed to have fallen from his eyes, and he saw clearly where he might quite conceivably have been making a grave blunder all these years. Deeply as he had always loved Pat, he had never—now he came to think of it—told her so. And in this sort of situation the spoken word is quite apt to make all the difference.

Perhaps that was why she laughed at him so frequently—because she was entertained by the spectacle of a man obviously in love with her refraining year after year from making any verbal comment on the state of his emotions.

Resolution poured over John in a strengthening flood. He looked at his watch. It was nearly 3. If he got the two-seater and started at once, he could be in London by 7, in nice time to take her to dinner somewhere. He hurried down the stairs and out into the stable yard.

“Shove that car out of the way, Bolt,” said John, eluding Emily, who, wet to the last hair, was endeavoring to climb up him. “I want to get the two-seater.”

“Two-seater, sir?”

“Yes. I’m going to London.”

“It’s not there, Mr. John,” said the chauffeur, with the gloomy satisfaction which he usually reserved for telling his employer that the battery had run down.

“Not there? What do you mean?”

“Mr. Hugo took it, sir, an hour ago. He told me he was going over to see Mr. Carmody at Healthward Ho. Said he had important business and knew you wouldn’t object.”

The stable yard reeled before John. Not for the first time in his life, he cursed his light-hearted cousin. “Knew you wouldn’t object”! It was just the fat-headed sort of thing Hugo would have said.

IV

THERE is something about those repellent words, Healthward Ho, that has a familiar ring. You feel that you have heard them before. And then you remember. They have figured in letters to the daily papers from time to time:

The Strain of Modern Life

To the Editor, The Times.

Sir:

In connection with the recent correspondence in your columns on the strain of modern life, I wonder if any of your readers are aware that there exists in the county of Worcestershire an establishment expressly designed to correct this strain.

At Healthward Ho (formerly Graveney Court), under the auspices of the well known American physician and physical culture expert, Dr. Alexander Twist, it is possible for those who have allowed the demands of modern life to tax their physique too greatly to recuperate in ideal surroundings, and by means of early hours, wholesome exercise, and Spartan fare to build up once more their debilitated tissues.

It is the boast of Dr. Twist that he makes new men for old.

I am, sir,

Yrs. etc.,

Mens Sana in Corpore Sano.

Do We Eat Too Much?

To the Editor, Daily Mail.

Sir:

The correspondence in your columns on the above subject calls to mind a remark made to me not long ago by Dr. Alexander Twist, the well known American physician and physical culture expert.

“Overeating,” said Dr. Twist emphatically, “is the curse of the age.”

At Healthward Ho (formerly Graveney Court), his physical culture establishment in Worcestershire, wholesome exercise and Spartan fare are the order of the day, and Dr. Twist has, I understand, worked miracles with the most apparently hopeless cases.

It is the boast of Dr. Twist that he makes new men for old.

I am, sir,

Yrs. etc.,

Moderation in All Things.

Should the Chaperon Be Restored?

To the Editor, Daily Express.

Sir:

A far more crying need than that of the chaperon in these modern days is for a supervisor of the middle-aged man who has allowed himself to get “out of shape.”

At Healthward Ho (formerly Graveney Court), in Worcestershire, where Dr. Alexander Twist, the well known American physician and physical culture expert, ministers to such cases, wonders have been achieved by means of simple fare and mild, but regular, exercise.

It is the boast of Dr. Twist that he makes new men for old.

I am, sir,

Yrs. etc.,

Vigilant.

THESE letters and many others, though bearing a pleasing variety of signatures, proceeded in fact from a single gifted pen—that of Dr. Twist himself; and among that class of the public which consistently does itself too well when the gong goes, and yet is never wholly free from wistful aspirations toward a better liver, they had created a scattered but quite satisfactory interest in Healthward Ho.

Now, on this summer afternoon, he was enabled to look down from his study window at a group of no fewer than eleven clients, skipping with skipping ropes under the eye of his able and conscientious assistant, ex-Sergeant Major Flannery.

Sherlock Holmes—and even, on one of his bright days, Doctor Watson—could have told at a glance which of those muffled figures was Mr. Flannery. He was the only one who went in instead of out at the waistline. All the others were well up in the class of man whom Julius Cæsar once expressed a desire to have about him. And pre-eminent among them in stoutness, dampness, and general misery was Mr. Lester Carmody of Rudge Hall.

His distress, unlike that of his fellow sufferers, was mental as well as physical. He was allowing his mind, for the hundredth time, to dwell on the paralyzing cost of these hygienic proceedings.

Thirty guineas a week, thought Mr. Carmody as he bounded up and down. Four pound ten a day. Three shillings and ninepence an hour. Three solid farthings a minute. To meditate on these figures was like turning a sword in his heart. For Lester Carmody loved money as he loved nothing else in this world except a good dinner.

Dr. Twist turned from the window. A maid had appeared, bearing a card on a salver.

“Show him in,” said Dr. Twist, having examined this. And presently there entered a lissom young man in a gray flannel suit.

“Dr. Twist?”

“Yes, sir.”

The newcomer seemed a little surprised. It was as if he had been expecting something rather more impressive, and was wondering why, if the proprietor of Healthward Ho had the ability which he claimed to make new men for old, he had not taken the opportunity of effecting some alterations in himself. For Dr. Twist was a small man, and weedy. He had a snub nose and an expression of furtive slyness. And he wore a waxed mustache.

However, all this was not the visitor’s business. If a man wishes to wax his mustache, it is a matter between himself and his God.

“My name’s Carmody,” he said. “Hugo Carmody.”

“Yes. I got your card.”

“Could I have a word with my uncle?”

“Sure, if you don’t mind waiting a minute. Right now,” explained Dr. Twist, with a gesture toward the window, “he’s occupied.”

Hugo moved to the window, looked out, and started violently.

“Great Scott!” he exclaimed.

HE gaped down at the group below. Mr. Carmody and colleagues had now discarded the skipping ropes and were performing some unpleasant-looking bending and stretching exercises, holding their hands above their heads and swinging painfully from what one may loosely term their waists. It was a spectacle well calculated to astonish any nephew.

“How long has he got to go on like that?” asked Hugo, awed.

Dr. Twist looked at his watch.

“They’ll be quitting soon now. Then a cold shower and rubdown, and they’ll be through till lunch.”

“Cold shower?”

“Yes.”

“You mean to say you make my Uncle Lester take cold shower baths?”

“That’s right.”

“Good God!”

A look of respect came into Hugo’s face as he gazed upon this master of men. Anybody who, in addition to making him tie himself in knots under a blazing sun, could lure Uncle Lester within ten yards of a cold shower bath was entitled to credit.

“I suppose, after all this,” he said, “they do themselves pretty well at lunch?”

“They have a lean mutton chop apiece, with green vegetables and dry toast.”

“Is that all?”

“That’s all.”

“And to drink?”

“Just water.”

“Followed, of course, by a spot of port?”

“Certainly not.”

“You mean—literally—no port?”

“Not a drop. If your old man had gone easier on the port, he’d not have needed to come to Healthward Ho.”

“I say,” said Hugo, “did you invent that name?”

“Sure. Why?”

“Oh, I don’t know. I just thought I’d ask.”

“Say, while I think of it,” said Dr. Twist, “have you any cigarettes?”

“Oh, rather.” Hugo produced a bulging case. “Turkish this side, Virginian that.”

“Not for me. I was only going to say that, when you meet your uncle, just bear in mind he isn’t allowed tobacco.”

“Not allowed— You mean to say you tie Uncle Lester into a lover’s knot, shoot him under a cold shower, push a lean chop into him accompanied by water, and then don’t even let the poor old devil get his lips round a single gasper?”

“That’s right.”

“Well, all I can say is,” said Hugo, “it’s no life for a refined Nordic.”

Dazed by the information he had received, he began to potter aimlessly about the room. He was not particularly fond of his uncle: Mr. Carmody Senior’s practice of giving him no allowance and keeping him imprisoned all the year round at Rudge would alone have been enough to check anything in the nature of tenderness. But he did not think he deserved quite all that seemed to be coming to him at Healthward Ho.

He mused upon his uncle. A complex character. A man with Lester Carmody’s loathing for expenditure ought by rights to have been a simple liver, existing off hot milk and triturated sawdust, like an American millionaire. That Fate should have given him, together with his prudence in money matters, a recklessness as regarded the pleasures of the table seemed ironic.

“I see they’ve quit,” said Dr. Twist, with a glance out of the window. “If you want to have a word with your uncle, you could do it now. No bad news, I hope?”

“If there is, I’m the one that’s going to get it. Between you and me,” said Hugo, who had no secrets from his fellow men, “I’ve come to try to touch him for a bit of money.”

“Is that so?” said Dr. Twist, interested.

Anything to do with money always interested the well known American physician and physical culture expert.

“Yes,” said Hugo. “Five hundred quid, to be exact.”

He spoke a little despondently; for, having arrived at the window again, he was in a position now to take a good look at his uncle. And so forbidding had bodily toil and mental disturbance rendered the latter’s expression that he found the fresh young hopes with which he had started out on this expedition rapidly ebbing away.

IF Mr. Carmody were to burst—and he looked as if he might do so at any moment—he, Hugo, being his nearest of kin, would inherit; but, failing that, there seemed to be no cash in sight whatever.

“Though when I say ‘touch,’ ” he went on, “I don’t mean quite that. The stuff is really mine. My father left me a few thousand, you see, but most injudiciously made Uncle Lester my trustee; and I’m not allowed to get at the capital without the old blighter’s consent. And now a pal of mine in London has written, offering me a half share in a new night club which he’s starting if I will put up five hundred pounds.”

“I see.”

“And what I ask myself,” said Hugo, “is, will Uncle Lester part? That’s what I ask myself. I can’t say I’m betting on it.”

“Well, I wish you luck,” said Dr. Twist. “But don’t you try to bribe him with cigarettes.”

“Do what?”

“Bribe him with cigarettes. After they have been taking the treatment for a while, most of these birds would give their soul for a coffin nail.”

Hugo started. He had not thought of this; but, now that it had been called to his attention, he saw that it was most certainly an idea.

“And don’t keep him standing around longer than you can help. He ought to get under that shower as soon as possible.”

Hugo had an idea.

“I suppose I couldn’t tell him that, owing to my pleading and persuasion, you’ve consented to let him off a cold shower today?”

“No, sir.”

“It would help,” urged Hugo. “It might just sway the issue, as it were.”

“Sorry. He must have his shower. When a man’s been exercising and has got himself into a perfect lather of sweat—”

“Keep it clean,” said Hugo coldly. “There is no need to stress the physical side. Oh, very well, then; I suppose I shall have to trust to tact and charm of manner. But I wish to goodness I hadn’t got to spring business matters on him on top of what seems to have been a slightly hectic morning.”

He shot his cuffs, pulled down his waistcoat, and walked with a resolute step out of the room. He was about to try to get into the ribs of a man who for a lifetime had been saving up to be a miser, and who, even apart from this trait in his character, held the subversive view that the less money young men had, the better for them.

Hugo was a gay optimist, cheerful of soul and a mighty singer in the bathtub; but he could not feel very sanguine. However, the Carmodys were a bulldog breed. He decided to have a pop at it.

The result of Hugo’s efforts to dig money out of his uncle started him on a whimsical venture. Follow him in next week’s Liberty.

This site also has annotations to Money for Nothing as it appeared in book form.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums