Liberty, June 23, 1928

Part Two

THEORETICALLY, no doubt, the process of exercising flaccid muscles, opening hermetically sealed pores, and stirring up a liver which had long supposed itself off the active list ought to engender in a man a jolly sprightliness.

In practice, however, this is not always so. That Lester Carmody was in no radiant mood was shown at once by the expression on his face as he turned in response to Hugo’s yodel from the rear. In spite of all that Healthward Ho had been doing to Mr. Carmody this last ten days, it was plain that he had not yet got that good-will-to-all-men feeling.

Nor, at the discovery that a nephew whom he had supposed to be twenty miles away was standing at his elbow, did anything in the nature of sudden joy help to fill him with sweetness and light.

“How the devil did you get here?” were his opening words of welcome. His scarlet face vanished for an instant into the folds of a large handkerchief, then reappeared, wearing a look of acute concern.

“You didn’t,” he quavered, “come in the Dex-Mayo?”

A thought to shake the sturdiest man. It was twenty miles from Rudge Hall to Healthward Ho, and twenty miles back again from Healthward Ho to Rudge Hall. The Dex-Mayo, that voracious car, consumed a gallon of petrol for every ten miles it covered. And for a gallon of petrol they extorted from you nowadays the hideous sum of one shilling and sixpence halfpenny.

Forty miles, accordingly, meant—not including oil, wear and tear of engines, and depreciation of tires—a loss to his purse of over six shillings: a heavy price to pay for the society of a nephew whom he had disliked since boyhood.

“No, no,” said Hugo hastily; “I borrowed John’s two-seater.”

“Oh,” said Mr. Carmody, relieved.

There was a pause, employed by Mr. Carmody in puffing; by Hugo in trying to think of something to say that would be soothing, tactful, ingratiating, and calculated to bring home the bacon. He turned over in his mind one or two conversational gambits:

“Well, uncle, you look very rosy.”

Not quite right.

“I say, uncle, what ho the schoolgirl complexion!”

Absolutely no! The wrong tone altogether.

Ah! That was more like it. “Fit.” Yes, that was the word.

“You look very fit, uncle,” said Hugo.

MR. CARMODY’S reply to this was to make a noise like a buffalo pulling its foot out of a swamp. It might have been intended to be genial, or it might not. Hugo could not tell. However, he was a reasonable young man and he quite understood that it would be foolish to expect the milk of human kindness instantly to come gushing like a geyser out of a 220-pound uncle who had just been doing bending and stretching exercises. He must be patient and suave—the Sympathetic Nephew.

“I expect it’s been pretty tough going, though,” he proceeded. “I mean to say, all these exercises and cold showers and lean chops and so forth. Terribly trying. Very upsetting. A great ordeal. I think it’s wonderful the way you’ve stuck it out. Simply wonderful. It’s character that does it. That’s what it is—character. Many men would have chucked the whole thing up in the first two days.”

“So would I,” said Mr. Carmody, “only that damned doctor made me give him a check in advance for the whole course.”

Hugo felt damped. He had had some good things to say about character, but it seemed little use producing them now.

“Well, anyway, you look fit. Very fit indeed. Frightfully fit. Remarkably fit. Extraordinarily fit.”

He paused. This was getting him nowhere. He decided to leap straight to the point at issue. To put his fortune to the test, to win or lose it all.

“I say, Uncle Lester, what I really came about this afternoon was a matter of business.”

“Indeed? I supposed you had come merely to babble. What business?”

“You know a friend of mine named Fish?”

“I do not know a friend of yours named Fish.”

“Well, he’s a friend of mine. His name’s Fish.”

“What about him?”

“He’s starting a new night club.”

“I don’t care,” said Mr. Carmody, who did not.

“It’s just off Bond Street, in the heart of London’s pleasure-seeking area. He’s calling it The Hot Spot.”

The only comment Mr. Carmody vouchsafed on this piece of information was a noise like another buffalo. His face was beginning to lose its vermilion tinge, and it seemed possible that in a few moments he might come off the boil.

“I had a letter from him this morning. He says he will give me a half share if I put up five hundred quid.”

“Then you won’t get a half share,” predicted Mr. Carmody.

“But I’ve got five hundred. I mean to say, you’re holding a lot more than that in trust for me.”

“Holding,” said Mr. Carmody, “is the right word.”

“BUT surely you’ll let me have this quite trivial sum for a really excellent business venture that simply can’t fail? Ronnie knows all about night clubs. He’s practically lived in them since he came down from Cambridge.”

“I shall not give you a penny. Have you no conception of the duties of a trustee? Trust money has to be invested in gilt-edged securities.”

“You’ll never find a gilter-edged security than a night club run by Ronnie Fish.”

“If you have finished this nonsense I will go and take my shower bath.”

“Well, look here, uncle. May I invite Ronnie to Rudge, so that you can have a talk with him?”

“You may not. I have no desire to talk with him.”

“You’d like Ronnie. He has an aunt in the looney-bin.”

“Do you consider that a recommendation?”

“No, I just mentioned it.”

“Well, I refuse to have him at Rudge.”

“But listen, uncle. The vicar will be round any day now to get me to perform at the village concert. If Ronnie were on the spot, he and I could do the Quarrel Scene from Julius Cæsar and really give the customers something for their money.”

EVEN this added inducement did not soften Mr. Carmody.

“I will not invite your friend to Rudge.”

“Right ho,” said Hugo, a game loser.

He was disappointed, but not surprised. All along he had felt that that Hot Spot business was merely a Utopian dream. There are some men who are temperamentally incapable of parting with £500, and his Uncle Lester was one of them. But in the matter of a smaller sum it might be that he would prove more pliable, and of this smaller sum Hugo had urgent need.

“Well, then, putting that aside,” he said, “there’s another thing I’d like to chat about for a moment, if you don’t mind.”

“I do,” said Mr. Carmody.

“There’s a big fight on tonight at the Albert Hall. Eustace Rodd and Cyril Warburton are going twenty rounds for the welterweight championship.

“Have you ever noticed,” said Hugo, touching on a matter to which he had given some thought, “a rather odd thing about boxers these days? A few years ago you never heard of one that wasn’t Beefy This or Porky That or Young Catsmeat or something. But now they’re all Claudes and Harolds and Cuthberts. And when you consider that the heavyweight champion of the world is actually named Eugene, it makes you think a bit.

“However, be that as it may, these two birds are going twenty rounds tonight, and there you are.”

“What,” inquired Mr. Carmody, “is all this drivel?”

He eyed his young relative balefully.

“I only meant to point out that Ronnie Fish has sent me a ticket, and I thought that, if you were to spring a tenner for the necessary incidental expenses—bed, breakfast, and so on—well, there I would be, don’t you know.”

“You mean you wish to go to London to see a boxing contest?”

“That’s it.”

“Well, you’re not going. You know I have expressly forbidden you to visit London. The last time I was weak enough to allow you to go there, what happened? You spent the night in the police station.”

“Yes; but that was boat-race night.”

“And I had to pay five pounds for your fine.”

Hugo dismissed the past with a gesture.

“The whole thing,” he said, “was an unfortunate misunderstanding; and, if you ask me, the verdict of posterity will be that the policeman was far more to blame than I was. They’re letting a bad type of man into the force nowadays. I’ve noticed it on several occasions. Besides, it won’t happen again.”

“You are right. It will not.”

“On second thoughts, then, you will spring that tenner?”

“On first, second, third, and fourth thoughts, I will do nothing of the kind!”

“But, uncle, do you realize what it would mean if you did?”

“The interpretation I would put upon it is that I was suffering from senile decay.”

“What it would mean is that I should feel you trusted me, Uncle Lester—that you had faith in me. There’s nothing so dangerous as want of trust. Ask anybody. It saps a young man’s character.”

“Let it,” said Mr. Carmody callously.

“If I went to London, I could see Ronnie Fish and explain all the circumstances about my not being able to go into that Hot Spot thing with him.”

“You can do that by letter.”

“It’s so hard to put things properly in a letter.”

“Then put them improperly,” said Mr. Carmody. “Once and for all, you are not going to London.”

HE had started to turn away as the only means possible of concluding this interview, when he stopped, spellbound. For Hugo, as was his habit when matters had become difficult and required careful thought, was pulling out of his pocket a cigarette case.

“Goosh!” said Mr. Carmody—or something that sounded like that.

He made an involuntary motion with his hand, as a starving man will make toward bread; and Hugo, with a strong rush of emotion, realized that the happy ending had been achieved and that at the eleventh hour matters could at last be put on a satisfactory business basis.

“Turkish this side, Virginian that,” he said. “You can have the lot for ten quid.”

“Say, I think you’d best be getting along and taking your shower, Mr. Carmody,” said the voice of Dr. Twist, who had come up unobserved and was standing at his elbow.

The proprietor of Healthward Ho had a rather unpleasant voice, but never had it seemed so unpleasant to Mr. Carmody as it did at that moment. Parsimonious though he was, he would have given much for the privilege of heaving a brick at Dr. Twist. For at the very instant of this interruption he had conceived the Machiavellian idea of knocking the cigarette case out of Hugo’s hand and grabbing what he could from the débris; and now this scheme must be abandoned.

With a snort which came from the very depths of an overwrought soul, Lester Carmody turned and shuffled off toward the house.

“Say, you shouldn’t have done that,” said Dr. Twist, waggling a reproachful head at Hugo. “No, sir, you shouldn’t have done that. Not right to tantalize the poor fellow.”

HUGO’S mind seldom ran on parallel lines with that of his uncle. But it was animated now by the identical thought which only a short while back Mr. Carmody had so wistfully entertained. He, too, was feeling that what Dr. Twist needed was a brick thrown at him. When he was able to speak, however, he did not mention this, but kept the conversation on a pacific and businesslike note.

“I say,” he said, “you couldn’t lend me a tenner, could you?”

“I could not,” agreed Dr. Twist.

“Well, I’ll be pushing along, then,” Hugo said moodily.

“I hope,” said Dr. Twist, as he escorted his young guest to his car, “you aren’t sore at me for calling you down about those student’s lamps. You see, maybe your uncle was hoping you would slip him one, and the disappointment will have made him kind of mad. And part of the system here is to have the patients think tranquil thoughts.”

“Think what?”

“Tranquil, beautiful thoughts. You see, if your mind’s all right your body’s all right. That’s the way I look at it.”

Hugo settled himself at the wheel.

“Let’s get this clear,” he said. “You expect my Uncle Lester to think beautiful thoughts?”

“All the time.”

“Even under a cold shower?”

“Yes, sir.”

“God bless you!” said Hugo.

He stepped on the self-starter and urged the two-seater pensively down the drive. As he turned the first corner, there popped out suddenly from a rhododendron bush a stout man with a red and streaming face. Lester Carmody had had to hurry, and he was not used to running.

“Woof!” he ejaculated, barring the fairway.

Relief flooded over Hugo. The marts of trade had not been closed, after all.

“Give me those cigarettes!” panted Mr. Carmody.

For an instant Hugo toyed with the idea of creating a rising market. But he was no profiteer. Hugo Carmody, the square dealer.

“Ten quid,” he said, “and they’re yours.”

Agony twisted Mr. Carmody’s glowing features.

“Five,” he urged.

“Ten,” said Hugo.

“Eight.”

“Ten.”

Mr. Carmody made the great decision.

“Very well. Give me them. Quick!”

“Turkish this side, Virginian that,” said Hugo.

The rhododendron bush quivered once more from the passage of a heavy body. Birds in the neighboring trees began to sing again their anthems of joy. And Hugo, in his trousers pocket two crackling five-pound notes, was bowling off along the highway.

Even Dr. Twist could have found nothing to cavil at in the beauty of the thoughts he was thinking. He caroled like a linnet in the springtime.

“Yes, sir,” he was assuring a listening world as he turned the two-seater in at the entrance of the stable yard of Rudge Hall some thirty minutes later, “that’s my baby. No, sir, don’t mean maybe. Yes, sir, that’s my baby now. And by the way, by the way—”

“Blast you,” said his cousin John, appearing from nowhere. “Get out of that car!”

“Hullo, John,” said Hugo. “So there you are, John. I say, John, I’ve just been paying a call on the head of the family over at Healthward Ho. Why they don’t run excursion trains of sight-seers there is more than I can understand. It’s worth seeing, believe me. Large, fat men doing bending and stretching exercises. Tons of humanity leaping about with skipping ropes. Never a dull moment from start to finish. And all clean, wholesome fun, mark you, without a taint of vulgarity or suggestiveness. Pack some sandwiches and bring the kiddies. And let me tell you the best thing of all, John—”

“I can’t stop to listen. You’ve made me late already.”

“Late for what?”

“I’m going to London.”

“You are?” said Hugo, with a smile at the happy coincidence. “So am I. You can give me a lift.”

“I won’t.”

“I am certainly not going to run behind.”

“You’re not going to London.”

“You bet I’m going to London!”

“Well, go by train, then.”

“And break into hard-won cash, every penny of which will be needed for the big time in the metropolis? A pretty story.”

“Well, anyway, you aren’t coming with me.”

“Why not?”

“I don’t want you.”

“JOHN,” said Hugo, “there is more in this than meets the eye. You can’t deceive me. You are going to London for a purpose. What purpose?”

“If you really want to know, I’m going to see Pat.”

“What on earth for? She’ll be here tomorrow. I looked in at Chas. Bywater’s this morning for some cigarettes—and, gosh, how lucky it was I did!—by the way he’s putting them down to you—and he told me she’s arriving by the three o’clock train.”

“I know. Well, I happen to want to see her very particularly tonight.”

Hugo eyed his cousin narrowly.

“John,” he said, “this can mean but one thing. You are driving a hundred miles in a shaky car—that left front tire wants a spot of air; I should look to it before you start, if I were you—to see a girl whom you could see tomorrow in any case by the simple process of meeting the three o’clock train. Your state of mind is such that you prefer—actually prefer—not to have my company. And, as I look at you, I note that you are blushing prettily. I see it all! You’ve at last decided to propose to Pat. Am I right or wrong?”

John drew a deep breath. He was not one of those men who derive pleasure from parading their inmost feelings and discussing with others the secrets of their hearts. Hugo, in a similar situation, would have advertised his love like the hero of a musical comedy; he would have made the round of his friends, confiding in them; and, when the supply of friends had given out, would have buttonholed the gardener.

But John was different. To hear his aspirations put into bald words like this made him feel as if he were being divested of most of his more important garments in a crowded thoroughfare.

“Well, that settles it,” said Hugo briskly. “Such being the case, of course you must take me along. I will put in a good word for you—pave the way.”

“Listen,” said John, finding speech. “If you dare to come within twenty miles of us—”

“It would be wiser. You know what you’re like. Heart of gold, but no conversation. Try to tackle this on your own and you’ll bungle it.”

“YOU keep out of this,” said John, speaking in a low, husky voice that suggested the urgent need of one of those throat lozenges purveyed by Chas. Bywater and so esteemed by the dog Emily. “You keep right out of this.”

Hugo shrugged his shoulders.

“Just as you please. Hugo Carmody is the last man,” he said, a little stiffly, “to thrust his assistance on those who do not require same. But a word from me would make all the difference, and you know it. Rightly or wrongly, Pat has always looked up to me, regarded me as a wise elder brother, and, putting it in a nutshell, hung upon my lips. I could start you off right.

“However, since you’re so blasted independent, carry on. Only, bear this in mind: when it’s all over and you are shedding scalding tears of remorse and thinking of what might have been, don’t come yowling to me for sympathy, because there won’t be any.”

John went upstairs and packed his bag. He packed well and thoroughly. This done, he charged down the stairs, and perceived with annoyance that Hugo was still inflicting the stable yard with his beastly presence.

But Hugo was not there to make jarring conversation. He was present now, it appeared, solely in the capacity of good angel.

“I’ve fixed up that tire,” said Hugo, “and filled the tank, and put in a drop of oil, and passed an eye over the machinery in general. She ought to run nicely now.”

John melted. His mood had softened, and he was in a fitter frame of mind to remember that he had always been fond of his cousin.

“Thanks. Very good of you. Well, good-by.”

“Good-by,” said Hugo. “And heaven speed your wooing, boy.”

Freed from the restrictions placed upon a light two-seater by the ruts and hillocks of country lanes, John celebrated his arrival on the broad main road that led to London by placing a large foot on the accelerator and keeping it there. He was behind time, and he intended to test a belief which he had long held, that a Widgeon Seven can, if pressed, do fifty.

To the scenery, singularly beautiful in this part of England, he paid no attention. Automatically avoiding wagons by an inch and dreamily putting thoughts of the hereafter into the startled minds of dogs and chickens, he was out of Worcestershire and into Gloucestershire almost before he had really settled in his seat.

It was only when the long wall that fringes Blenheim Park came into view that it was borne in upon him that he would be reaching Oxford in a few minutes and could stop for a well earned cup of tea. He noted with satisfaction that he was nicely ahead of the clock. He drifted past the Martyrs’ Memorial, and, picking his way through the traffic, drew up at the door of the Clarendon. He alighted stiffly, and stretched himself. And, as he did so, something caught his attention out of the corner of his eye. It was his Cousin Hugo, climbing down from the dickey.

“A very nice run,” said Hugo with satisfaction. “I should say we made pretty good time.”

HE radiated kindliness and satisfaction with all created things. That John was looking at him in rather a peculiar way and apparently trying to say something, he did not seem to notice.

“A little refreshment would be delightful,” he observed. “Dusty work, sitting in dickeys. By the way, I got on to Pat on the phone before we left, and there’s no need to hurry. She’s dining out and going to a theater tonight.”

“What?” cried John, in agony.

“It’s all right. Don’t get the wind up. She’s meeting us at eleven-fifteen at the Mustard Spoon. I’ll come on there from the fight and we’ll have a nice home evening. I’m still a member, so I’ll sign you in. And, what’s more, if all goes well at the Albert Hall and Cyril Warburton is half the man I think he is and I can get some sporting stranger to bet the other way at reasonable odds, I’ll pay the bill.”

“You’re very kind!”

“I try to be, John,” said Hugo modestly. “I try to be. I don’t think we ought to leave it all to the Boy Scouts.”

II

A MAN whose uncle jerks him away from London as if he were picking a winkle out of its shell with a pin, and keeps him for months and months immured in the heart of Worcestershire must inevitably lose touch with the swiftly changing kaleidoscope of metropolitan night life. Nothing in a big city fluctuates more rapidly than the status of its supper-dancing clubs; and Hugo, had he still been a lad about town in good standing, would have been aware that recently the Mustard Spoon had gone down a good deal in the social scale.

To John Carroll, however, as he stood waiting in the lobby, the place seemed sufficiently gay and glittering. Nearly a year had passed since his last visit to London, and the Mustard Spoon rather impressed him. An unseen orchestra was playing with extraordinary vigor, and from time to time ornate persons of both sexes drifted past him into the brightly lighted supper room. Where an established connoisseur of night clubs would have pursed his lips and shaken his head, John was conscious only of feeling decidedly uplifted and exhilarated.

But then, he was going to see Pat again, and that was enough to stimulate any man.

She arrived unexpectedly, at a moment when he had taken his eye off the door to direct it in mild astonishment at a lady in an orange dress who, doubtless with the best motives, had dyed her hair crimson and was wearing a black-rimmed monocle. So absorbed was he with this spectacle that he did not see Pat enter, and was made aware of her presence only when there spoke from behind him a clear little voice which, even when it was laughing at you, always seemed to have in it something of the song of larks on summer mornings and winds whispering across the fields in spring.

“Hullo, Johnny.”

The hair, scarlet though it was, lost its power to attract. The appeal of the monocle waned. John spun round.

“Pat!”

She was looking lovelier than ever. That was the thing that first presented itself to John’s notice. If anybody had told him that Pat could possibly be prettier than the image of her which he had been carrying about with him all these months, he would not have believed him. But so it was.

Some sort of a female with plucked eyebrows and a painted face had just come in, and she might have been put there expressly for purposes of comparison. She made Pat seem so healthy, so wholesome, such a thing of the open air and the clean sunshine, so pre-eminently fit. She looked as if she had spent her time at Le Touquet playing thirty-six holes of golf a day.

“Pat!” cried John—and something seemed to catch at his throat. There was a mist in front of his eyes. His heart was thumping madly.

She extended her hand composedly. Her demeanor was friendly, but matter-of-fact.

“Well, Johnny. How nice to see you again! You’re looking very brown and rural. Where’s Hugo?”

It takes two to hoist a conversation to an emotional peak. John choked and became calmer.

“He’ll be here soon, I expect,” he said.

Pat laughed indulgently.

“Hugo’ll be late for his own funeral—if he ever gets to it. He said eleven-fifteen and it’s twenty-five to twelve. Have you got a table?”

“Not yet.”

“Why not?”

“I’m not a member,” said John and saw in her eyes the scorn which women reserve for male friends and relations who show themselves wanting in enterprise. “You have to be a member,” he said, chafing under the look.

“I don’t,” said Pat with decision. “If you think I’m going to wait all night for old Hugo in a small lobby with six drafts whizzing through it, correct that impression. Go and find the head waiter and get a table while I leave my cloak. Back in a minute.”

The head waiter was a large, stout, smooth-faced man who would have been better for a couple of weeks at Healthward Ho, and he gave the impression of having disliked John from the start.

JOHN said it was a nice evening. The head waiter did not seem to believe him.

“Has—er—has Mr. Carmody booked a table?” asked John.

“No, monsieur.”

“I’m meeting him here tonight.”

The head waiter appeared uninterested. He began to talk to an underling in rapid French. John, feeling more than ever an intruder, took advantage of a lull in the conversation to make another attempt.

“I wonder—perhaps—can you give me a table?”

Most of the head waiter’s eyes were concealed by the upper strata of his cheeks; but there was enough of them left visible to allow him to look at John as if he were something unpleasant that had come to light in a portion of salad.

“Monsieur is a member?”

“Er—no.”

“If you will please wait in the lobby, thank you.”

“But I was wondering—”

“If you will wait in the lobby, please,” said the head waiter; and, dismissing John from the scheme of things, became gruesomely obsequious to an elderly man with diamond studs, no hair, an authoritative manner, and a lady in pink. He waddled before them into the supper room, and Pat reappeared.

“Got that table?”

“I’m afraid not. He says—”

“Oh, Johnny, you are maddening. Why are you so helpless?”

Women are unjust in these matters. When a man comes into a night club of which he is not a member and asks for a table, he feels that he is butting in and naturally is not at his best. This is not helplessness: it is fineness of soul. But women won’t see that.

“I’m awfully sorry.”

The head waiter had returned and was either doing sums or drawing caricatures on a large pad chained to a desk. He seemed so much the artist absorbed in his work that John would not have dreamed of venturing to interrupt him. Pat had no such delicacy.

“I want a table, please,” said Pat.

“Madame is a member?”

“A table, please. A nice, large one. I like plenty of room. And when Mr. Carmody arrives tell him that Miss Wyvern and Mr. Carroll are inside.”

“Very good, madame. Certainly, madame. This way, madame.”

Just as simple as that! John, making a physically impressive but spiritually negligible tail to the procession, wondered, as he crossed the polished floor, how Pat did these things.

It was not as if she were one of those massive, imperious women whom you would naturally expect to quell head waiters with a glance. She was no Cleopatra, no Catherine of Russia—just a slim, slight girl with a tiptilted nose. And yet, she had taken this formidable magnifico in her stride, kicked him lightly in the face, and passed on. John sat down, thrilled with a worshiping admiration.

Pat, as always happened after one of her little spurts of irritability, was apologetic.

“Sorry I bit your head off, Johnny,” she said. “It was a shame, after you had come all this way just to see an old friend. But it makes me so angry when you’re meek and sheepy and let people trample on you. Still, I suppose it’s not your fault.”

She smiled across at him.

“You always were a slow, good-natured old thing, weren’t you, like one of those big dogs that come and bump their head on your lap and snuffle. Poor old Johnny!”

John felt depressed. This “Poor old Johnny!” stuff struck just the note he most wanted to avoid. If one thing is certain in the relations of the sexes, it is that the poor old Johnnies of this world get nowhere. But before he could put any of these feelings into words Pat had changed the subject.

“Johnny,” she said, “what’s all this trouble between your uncle and father? I had a letter from father a couple of weeks ago, and as far as I could make out Mr. Carmody seems to have been trying to murder him. What’s it all about?”

Not so eloquently, nor with such a wealth of imagery as Colonel Wyvern had employed in sketching out the details of the affair of the dynamite outrage for the benefit of Chas. Bywater, Chemist, John answered the question.

“Good heavens!” said Pat.

“I—I hope—” said John.

“What do you hope?”

“Well, I—I hope it’s not going to make any difference—between you and me, Pat.”

“What sort of difference?”

John had his cue.

“Pat darling, in all these years we’ve known each other, haven’t you ever guessed that I’ve been falling more and more in love with you every minute? I can’t remember a time when I didn’t love you. I loved you as a kid in short skirts and a blue jersey. I loved you when you came back from that school of yours, looking like a princess. And I love you now more than I have ever loved you.

“I worship you, Pat darling. I may have been poor old Johnny in the past, but the time has come when you’ve got to forget all that. I mean business. You’re going to marry me, and the sooner you make up your mind to it the better.”

THAT was what John had intended to say. What he actually did say was something briefer and altogether less effective.

“Oh, I don’t know,” said John.

“Do you mean you’re afraid I’m going to stop being friends with you just because my father and your uncle have had a quarrel?”

“Yes,” said John. It was not quite all he had meant, but it gave the general idea.

“What a weird notion! After all these years? Good heavens, no! I’m much too fond of you, Johnny.”

Once more John had his cue. And this time he stiffened his courage. He cleared his throat. He clutched the tablecloth.

“Pat—”

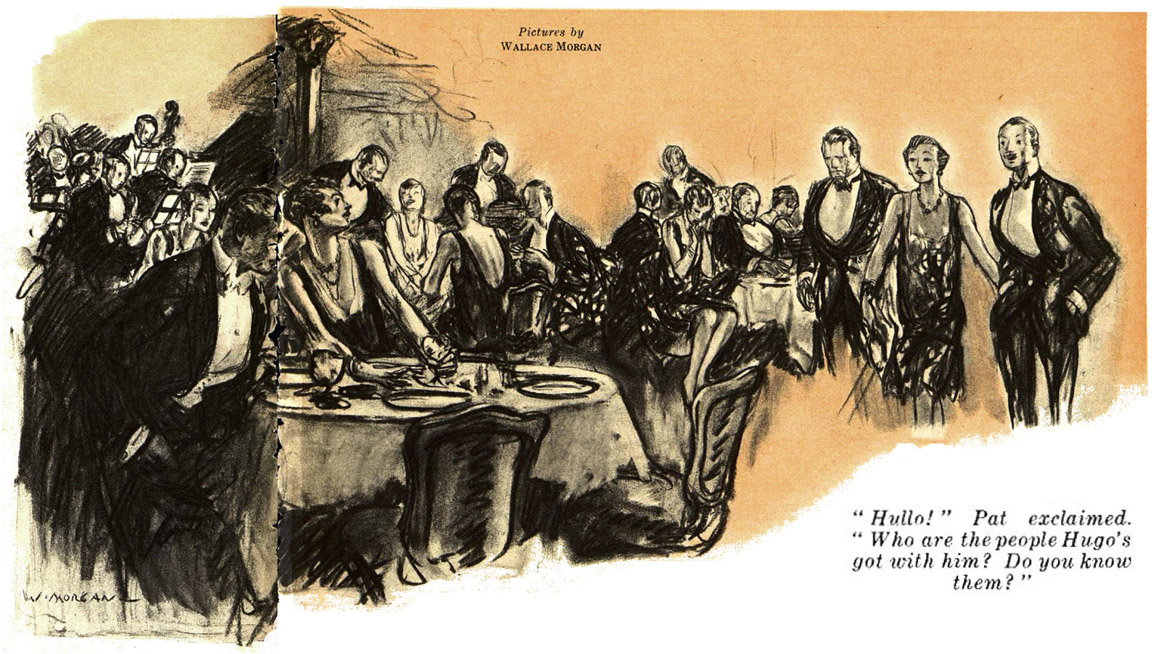

“Oh, there’s Hugo at last,” she said, looking past him. “And about time. I’m starving. Hullo! Who are the people he’s got with him? Do you know them?”

John heaved a silent sigh. Yes, he could have counted on Hugo arriving at just this moment. He turned and perceived that unnecessary young man crossing the floor. With him were a middle-aged man and a younger and extremely dashing-looking girl. They were complete strangers to John.

Complete strangers—yet John would have been amazed could he have foreseen the part they were destined to play in his life. Watch their maneuvers in next week’s installment.

The magazine typesetter omitted the first hyphen in “good-will-to-all-men” in the second paragraph; corrected here for consistency.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums