Liberty, August 18, 1928

Part Ten

LEFT alone, John walked to the window and frowned meditatively out. His brain was now working with a rapidity and clearness which the most professional of detectives might have envied. For the first time since his cousin Hugo had come to him to have his head repaired, he began to realize that there might have been something, after all, in that young man’s rambling story. Taken in conjunction with what Sturgis had just told him, Hugo’s weird tale of finding Dr. Twist burgling the house became significant.

This Twist, now. After all, what about him? He had come from nowhere to settle down in Worcestershire, ostensibly in order to conduct a health farm. But what if that health farm were a mere blind for more dastardly work? After all, it was surely a commonplace that your scientific criminal invariably adopted some specious cover of respectability for his crimes.

Into the radius of John’s visions there came Mr. Thomas G. Molloy, walking placidly beside the moat with his dashing daughter. It seemed to John as if he had been sent at just this moment for a purpose. What he wanted above all things was a keen minded, sensible man of the world with whom to discuss these suspicions of his, and who was better qualified for this rôle than Mr. Molloy?

Long since, he had fallen under the spell of the other’s magnetic personality and had admired the breadth of his intellect. Thomas G. Molloy was, it seemed to him, the ideal confidant.

He left the room hurriedly, and ran down the stairs.

MR. MOLLOY was still strolling beside the moat when John arrived. He greeted him with his usual bluff kindliness. Soapy, like John some half hour earlier, was feeling amiably disposed toward all mankind this morning.

“Well, well, well!” said Soapy. “So you’re back? Did you have a pleasant time in London?”

“All right, thanks. I wanted to see you—”

“You’ve heard about this unfortunate business last night?”

“Yes. It was about that—”

“I have never been so upset by anything in my life,” said Mr. Molloy. “By pure bad luck Dolly, here, and myself went over to Birmingham after dinner to see a show, and in our absence the outrage must have occurred. I venture to say,” went on Mr. Molloy, a stern look creeping into his eyes, “that if only I’d been on the spot the thing could never have happened. My hearing’s good, and I’m pretty quick on a trigger, Mr. Carroll—pretty quick, let me tell you. It would have taken a right smart burglar to have gotten past me.”

“You bet it would,” said Dolly. “Gee! It’s a pity. And the man didn’t leave a single trace, did he?”

“A fingerprint—or it may have been a thumbprint—on the sill of the window, honey. That was all. And I don’t see what good that’s going to do us. You can’t round up the population of England and ask to see their thumbs.”

“And outside of that not so much as a single trace. Isn’t it too bad! From start to finish not a soul set eyes on the fellow.”

“Yes, they did,” said John. “That’s what I came to talk to you about. One of the servants heard a noise and came out and saw him going down the staircase.”

If he had failed up to this point to secure the undivided attention of his audience, he had got it now. Miss Molloy seemed suddenly to become all eyes, and so tremendous was the joy and relief of Mr. Molloy that he actually staggered.

“Saw him?” exclaimed Miss Molloy.

“Sus-saw him?” echoed her father, scarcely able to speak in his delight.

“Yes. Do you by any chance know a man named Twist?”

“Twist?” said Mr. Molloy, still speaking with difficulty. He wrinkled his forehead. “Twist? Do I know a man named Twist, honey?”

“The name seems kind of familiar,” admitted Miss Molloy.

“He runs a place called Healthward Ho about twenty miles from here. My uncle stayed there for a couple of weeks. It’s a place where people go to get into condition—a sort of health farm, I suppose you would call it.”

“Of course, yes. I have heard Mr. Carmody speak of his friend Twist. But—”

“Apparently he called here the other day—to see my uncle, I suppose—and this servant I’m speaking about saw him, and is convinced that he was the burglar.”

“Improbable, surely?” Mr. Molloy seemed still to be having a little trouble with his breath. “Surely not very probable? This man Twist, from what you tell me, is a personal friend of your uncle. Why, therefore— Besides, if he owns a prosperous business—”

John was not to be put off the trail by mere superficial argument. Doctor Watson may be slow at starting, but, once started, he is a bloodhound for tenacity.

“I’ve thought of all that. I admit it did seem curious at first. But, if you come to look into it, you can see that the very thing a burglar who wanted to operate in these parts would do is to start some business that would make people unsuspicious of him.”

Mr. Molloy shook his head.

“It sounds far-fetched to me.”

JOHN’S opinion of his sturdy good sense began to diminish.

“Well, anyhow,” he said in his solid way, “this servant is sure he recognized Twist, and one can’t do any harm by going over there and having a look at the man. I’ve got quite a good excuse for seeing him. My uncle’s having a dispute about his bill, and I can say I came over to discuss it.”

“Yes,” said Mr. Molloy in a strained voice. “But—”

“Sure you can,” said Miss Molloy, with sudden animation. “Smart of you to think of that. You need an excuse, if you don’t want to make this Twist fellow suspicious.”

“Exactly,” said John.

He looked at the girl with something resembling approval.

“And there’s another thing,” proceeded Miss Molloy, warming to her subject. “Don’t forget that this bird, if he’s the man that did the burgling last night, has a cut finger or thumb. If you find this Twist is going around with sticking plaster on him, why, then that’ll be evidence.”

John’s approval deepened.

“That’s a great idea,” he agreed. “What I was thinking was that I wanted to find out if Twist has a cold in the head.”

“A kuk-kuk-kuk . . .?” said Mr. Molloy.

“Yes. You see, the burglar had. He was sneezing all the time, my informant tells me.”

“Well, say, this begins to look like the goods,” cried Miss Molloy gleefully. “If this fellow has a cut thumb and a cold in the head, there’s nothing to it. It’s all over except tearing off the false whiskers and saying ‘I am Hawkshaw, the detective!’

“Say, listen. You get that little car of yours out, and you and I will go right over to Healthward Ho now. You see, if I come along, that’ll make him all the more unsuspicious. We’ll tell him I’m a girl with a brother that’s been whooping it up a little too hearty for some time past, and I want to make inquiries with the idea of putting him where he can’t get the stuff for a while.

“I’m sure you’re on the right track. This bird Twist is the villain of the piece, I’ll bet a million dollars. As you say, a fellow that wanted to burgle houses in these parts just naturally would settle down and pretend to be something respectable. You go and get that car out, Mr. Carroll, and we’ll be off right away.”

John reflected. Filled though he was with the enthusiasm of the chase, he could not forget that his time today was earmarked for other and higher things than the investigation of the mysterious Dr. Twist of Healthward Ho.

“I must be back here by a quarter to one,” he said.

“Why?”

“I must.”

“Well, that’s all right. We’re not going to spend the week-end with this guy. We’re simply going to take a look at him. As soon as we’ve done that, we’ll come right home and turn the thing over to the police. It’s only twenty miles. You’ll be back here again before twelve.”

“Of course,” said John. “You’re perfectly right. I’ll have the car out in a couple of minutes.”

He hurried off. His views concerning Miss Molloy now were definitely favorable. She might not be the sort of girl he could ever like; she might not be the sort of girl he wanted staying at the Hall; but it was idle to deny that she had her redeeming qualities. About her intelligence, for instance, there was, he felt, no doubt whatsoever.

AND yet, it was with regard to this intelligence that Soapy Molloy was at this very moment entertaining doubts of the gravest kind. His eyes were protruding a little, and he uttered an odd, strangled sound.

“It’s all right, you poor sap,” said Dolly, meeting his shocked gaze with a confident unconcern.

Soapy found speech.

“All right? You say it’s all right? How’s it all right? If you hadn’t pulled all that stuff—”

“Say, listen!” said Dolly urgently. “Where’s your sense? He would have gone over to see Chimp anyway, wouldn’t he? Nothing we could have done would have headed him off from that, would it? And he’d have noticed Chimp had a cut finger without my telling him, wouldn’t he? All I’ve done is to make him think I’m on the level and working in cahoots with him.”

“What’s the use of that?”

“I’ll tell you what use it is. I know what I’m doing. Listen, Soapy. You just race into the house and get those knockout drops and give them to me. And make it snappy,” said Dolly.

AS when on a day of rain and storm there appears among the clouds a tiny gleam of blue, so now, at those magic words “knockout drops” did there flicker into Mr. Molloy’s somber face a faint suggestion of hope.

“Don’t you worry, Soapy. I’ve got this thing well in hand. When we’ve gone, you jump to the phone and get Chimp on the wire and tell him this guy and I are on our way over. Tell him I’m bringing the kayo drops and I’ll slip them to him as soon as I arrive. Tell him to be sure to have something to drink handy and to see that this bird gets a taste of it.”

“I get you, pettie!”

Mr. Molloy’s manner was full of a sort of awe-struck reverence, like that of some humble adherent of Napoleon listening to his great leader outlining plans for a forthcoming campaign; nevertheless it was tinged with doubt. He had always admired his wife’s broad, spacious outlook, but she was apt sometimes, he considered, in her fresh young enthusiasm, to overlook details.

“But, pettie,” he said, “is this wise? Don’t forget you’re not in Chicago now. I mean, supposing you do put this fellow to sleep, he’s going to wake up pretty soon, isn’t he? And when he does, won’t he raise an awful holler?”

“I’ve got that all fixed. I don’t know what sort of staff Chimp keeps over at that joint of his, but he’s probably got assistants and all like that. Well, you tell him to tell them that there’s a young lady coming over with a brother that wants looking after, and this brother has got to be given a sleeping draft and locked away somewheres to keep him from getting violent and doing somebody an injury. That’ll get him out of the way long enough for us to collect the stuff and clear out.

“It’s rapid action now, Soapy. Now that Chimp has gummed the game by letting himself be seen, we’ve got to move quick. We’ve got to make our get-away today. So don’t you go off wandering about the fields picking daisies after I’ve gone. You stick around that phone, because I’ll be calling you before long. See?”

“Honey,” said Mr. Molloy devoutly, “I always said you were the brains of the firm, and I always will say it. I’d never have thought of a thing like this myself in a million years.”

II

IT was about an hour later that Sergeant Major Flannery, seated at his ease beneath a shady elm in the garden of Healthward Ho, looked up from the novelette over which he had been relaxing his conscientious mind, and became aware that he was in the presence of Youth and Beauty.

Toward him, across the lawn, was walking a girl who, his experienced eye assured him at a single glance, fell into that limited division of the sex which is embraced by the word Pippin. Her willowy figure was clothed in some clinging material of a beige color, and her bright hazel eyes, when she came close enough for them to be seen, touched in the sergeant major’s susceptible bosom a ready chord.

He rose from his seat with easy grace; and his hand, falling from the salute, came to rest on the western section of his waxed mustache.

“Nice morning, miss,” he bellowed.

It seemed to Sergeant Major Flannery that this girl was gazing upon him as on some wonderful dream of hers that had unexpectedly come true; and he was thrilled. It was unlikely, he felt, that she was about to ask him to perform some great knightly service for her; but, if she did, he would spring smartly to attention and do it in a soldierly manner while she waited. Sergeant Major Flannery was pro-Dolly from the first moment of their meeting.

“Are you one of Dr. Twist’s assistants?” asked Dolly.

“I am his only assistant, miss. Sergeant Major Flannery is the name.”

“Oh? Then you look after the patients here?”

“That’s right, miss.”

“Then it is you who will be in charge of my poor brother?” She uttered a little sigh, and there came into her hazel eyes a look of pain.

“Your brother, miss? Are you the lady—”

“Did Dr. Twist tell you about my brother?”

“Yes, miss. The fellow who’s been—”

He paused, appalled. Only by a hair’s breadth had he stopped himself from using in the presence of this divine creature the hideous expression “mopping it up a bit.”

“Yes,” said Dolly. “I see you know about it.”

“All I know about it, miss,” said Sergeant Major Flannery, “is that the doctor had me into the orderly room just now and said he was expecting a young lady to arrive with her brother, who needed attention. He said I wasn’t to be surprised if I found myself called for to lend a hand in a rough-house, because this bloke—because this patient was apt to get verlent.”

“My brother does get very violent,” sighed Dolly. “I only hope he won’t do you an injury.”

Sergeant Major Flannery twitched his bananalike fingers and inflated his powerful chest. He smiled a complacent smile.

“He won’t do me an injury, miss. I’ve had experience with”—again he stopped just in time, on the very verge of shocking his companion’s ears with the ghastly noun “souses”—“with these sort of nervous cases,” he amended. “Besides, the doctor says he’s going to give the gentleman a little sleeping draft, which’ll keep him as you might say ’armless till he wakes up and finds himself under lock and key.”

“I see. Yes, that’s a very good idea.”

“No sense in troubling trouble till trouble troubles you, as the saying is, miss,” agreed the sergeant major. “If you can do a thing in a nice, easy, tactful manner without verlence, then why use verlence? Has the gentleman been this way long, miss?”

“For years.”

“You ought to have had him in a home sooner.”

“I have put him into dozens of homes. But he always gets out. That’s why I’m so worried.”

“He won’t get out of Healthward Ho, miss.”

“He’s very clever.”

IT was on the tip of Sergeant Major Flannery’s tongue to point out that other people were clever too, but he refrained—not so much from modesty as because at this moment he swallowed some sort of insect. When he had finished coughing, he found that his companion had passed on to another aspect of the matter.

“I left him alone with Dr. Twist. I wonder if that was safe.”

“Quite safe, miss,” the sergeant major assured her. “You can see the window’s open and the room’s on the ground floor. If there’s trouble and the gentleman starts any verlence, all the doctor’s got to do is to shout for ’elp, and I’ll get to the spot at the double and climb in and lend a hand.”

His visitor regarded him with a shy admiration.

“It’s such a relief to feel that there’s someone like you here, Mr. Flannery. I’m sure you are wonderful in any kind of an emergency.”

“People have said so, miss,” replied the sergeant major, stroking his mustache and smiling another quiet smile.

“But what’s worrying me is what’s going to happen when my brother comes to after the sleeping draft and finds that he is locked up. That’s what I meant just now when I said he was so clever. The last place he was in, they promised to see that he stayed there, but he talked them into letting him out. He said he belonged to some big family in the neighborhood and had been shut up by mistake.”

“He won’t get round me that way, miss.”

“Are you sure?”

“Quite sure, miss. If there’s one thing you get used to in a place like this, it’s artfulness. You wouldn’t believe how artful some of these gentlemen can be. Only yesterday that Admiral Sir Rigby-Rudd toppled over in my presence after doing his bending and stretching exercises, and said he felt faint, and he was afraid it was his heart, and would I go and get him a drop of brandy. Anything like the way he carried on when I just poured half a bucketful of cold water down his back instead, you never heard in your life.

“I’m on the watch all the time, I can tell you, miss. I wouldn’t trust my own mother if she was in here taking the cure. They just spend their whole time thinking up ways of being artful.”

“Do they ever try to bribe you?”

“No, miss,” said Mr. Flannery, a little wistfully. “I suppose they take a look at me and think—and see that I’m not the sort of fellow that would take bribes.”

“My brother is sure to offer you money to let him go.”

“How much—how much good,” said Sergeant Major Flannery carefully, “does he think that’s going to do him?”

“You wouldn’t take it, would you?”

“Who, me, miss? Take money to betray my trust, if you understand the expression?”

“Whatever he offers you I will double. You see, it’s so very important that he is kept here, where he will be safe from temptation, Mr. Flannery,” said Dolly timidly. “I wish you would accept this.”

THE sergeant major felt a quickening of the spirit as he gazed upon the rustling piece of paper in her hand.

“No, no, miss,” he said, taking it. “It really isn’t necessary.”

“I know. But I would rather you had it. You see, I’m afraid my brother may give you a lot of trouble.”

“Trouble’s what I’m here for, miss,” said Mr. Flannery bravely. “Trouble’s what I draw my salary for. Don’t you worry, miss. We’re going to make this brother of yours a different man. We—”

“Trouble’s what I’m here for, miss,” said Mr. Flannery bravely. “Trouble’s what I draw my salary for. Don’t you worry, miss. We’re going to make this brother of yours a different man. We—”

“Oh!” cried Dolly.

A head and shoulders had shot suddenly out of the study window—the head and shoulders of Dr. Twist. The voice of Dr. Twist sounded sharply above the droning of bees and insects:

“Flannery!”

“On the spot, sir.”

“Come here, Flannery. I want you.”

“You stay here, miss,” counseled Sergeant Major Flannery paternally. “There may be verlence.”

There were, however, when Dolly made her way to the study some five minutes later, no signs of anything of an exciting and boisterous nature having occurred recently in the room. The table was unbroken, the carpet unruffled. The chairs stood in their places, and not even a picture glass had been cracked.

It was evident that the operations had proceeded according to plan.

“Everything jake?” inquired Dolly.

“Uh-hum,” said Chimp—speaking, however in a voice that quavered a little.

Mr. Twist was the only object in the room that looked in any way disturbed. He had turned an odd greenish color, and from time to time he swallowed uneasily. Although he had spent a lifetime outside the law, Chimp Twist was essentially a man of peace and accustomed to look askance at any by-product of his profession that seemed to him to come under the heading of rough stuff. This doping of respectable visitors, he considered, was distinctly so to be classified; and only Mr. Molloy’s urgency over the telephone wire had persuaded him to the task. He was nervous and apprehensive, in a condition to start at sudden noises.

“What happened?”

“Well, I did what Soapy said. After you left us, the guy and I talk back and forth for a while, and then I agree to knock a bit off the old man’s bill, and then I said, ‘How about a little drink?’ and then we have a little drink, and then I slip the stuff you gave me in while he wasn’t looking. It didn’t seem like it was going to act at first.”

“It don’t. It takes a little time. You don’t feel nothing till you jerk your head or move yourself, and then it’s like as if somebody had beaned you one with an iron girder or something. So they tell me,” said Dolly.

“I guess he must have jerked his head, then. Because all of a sudden he went down and out,” Chimp gulped. “You—you don’t think he’s— I mean, you’re sure this stuff—?”

Dolly had nothing but contempt for these masculine tremors.

“Of course. Do you suppose I go about the place croaking people? He’s all right.”

“Well, he didn’t look it. If I’d been a life insurance company I’d have paid up on him without a yip.”

“He’ll wake up with a headache in a little while, but outside of that he’ll be as well as he ever was. Where have you been all your life, that you don’t know how kayo drops act?”

“I’ve never had occasion to be connected with none of this raw work before,” said Chimp virtuously. “If you’d of seen him when he slumped down on the table, you wouldn’t be feeling so good yourself, maybe. If ever I saw a guy that looked like he was qualified to step straight into a coffin, he was him.”

“Aw, be yourself, Chimp!”

“I’m being myself all right, all right.”

“Well, then, for Pete’s sake, be somebody else. Pull yourself together, why can’t you? Have a drink.”

“Ah!” said Mr. Twist, struck with the idea.

His hand was still shaking, but he accomplished the delicate task of mixing a whisky and soda without disaster.

“What did you do with the remains?” asked Dolly, interested.

MR. TWIST, who had been raising the glass to his lips, lowered it again. He disapproved of levity of speech at such a moment.

“Would you kindly not call him ‘the remains’?” he begged. “It’s all very well for you to be so easy about it all, and to pull this stuff about him doing nothing but wake up with a headache, but what I’m asking myself is, will he wake up at all?”

“Oh, cut it out! Sure he’ll wake up.”

“But will it be in this world?”

“You drink that up, you poor dumbbell, and then fix yourself another,” advised Dolly. “And make it a bit stronger next time. You seem to need it.”

Mr. Twist did as directed, and found the treatment beneficial.

“You’ve nothing to grumble at,” Dolly proceeded, still looking on the bright side. “What with all this excitement and all, you seem to have lost that cold of yours.”

“That’s right,” said Chimp, impressed. “It does seem to have got a whole lot better.”

“Pity you couldn’t have got rid of it a little earlier. Then we wouldn’t have had all this trouble. From what I can make of it, you seem to have roused the house by sneezing your head off, and a bunch of the help come and stood looking over the banisters at you.”

Chimp tottered. “You don’t mean somebody saw me last night?”

“Sure they saw you. Didn’t Soapy tell you that over the wire?”

“I couldn’t hardly make out all Soapy was saying over the wire. Say! What are we going to do?”

“Don’t you worry. We’ve done it. The only difficult part is over. Now that we’ve fixed the remains—”

“Will you please—”

“Well, call him what you like. Now that we’ve fixed that guy, the thing’s simple. By the way, what did you do with him?”

“Flannery took him upstairs.”

“Where to?”

“There’s a room on the top floor. Must have been a nursery or something, I guess. Anyway, there’s bars to the window.”

“How’s the door?”

“Good, solid oak. You’ve got to hand it to the guys who built these old English houses. They knew their groceries. When they spit on their hands and set to work to make a door, they made one. You couldn’t push that door down, not if you was an elephant.”

“Well, that’s all right, then. Now, listen, Chimp. Here’s the lowdown. We—” She broke off. “What’s that?”

“What’s what?” asked Mr. Twist, starting violently.

“I thought I heard someone outside in the corridor. Go and look.”

WITH an infinite caution born of alarm, Mr. Twist crept across the floor, reached the door, and flung it open. The passage was empty. He looked up and down it, and Dolly, whose fingers had hovered for an instant over the glass which he had left on the table, sat back with an air of content.

“My mistake,” she said. “I thought I heard something.”

Chimp returned to the table. He was still much perturbed.

“I wish I’d never gone into this thing,” he said, with a sudden gush of self-pity. “I felt all along, what with seeing that magpie and the new moon through glass—”

“Now, listen!” said Dolly vigorously. “Considering you’ve stood Soapy and me up for practically all there is in this thing except a little small change, I’ll ask you kindly, if you don’t mind, not to stand there beefing and expecting me to hold your hand and pat you on the head and be a second mother to you. You came into this business because you wanted to. You’re getting sixty-five per cent of the gross. So what’s biting you? You’re all right so far.”

It was in Mr. Twist’s mind to inquire of his companion precisely what she meant by this expression, but more urgent matters claimed his attention. More even than the exact interpretation of the phrase “so far,” he wished to know what the next move was.

“What happens now?” he asked.

“We go back to Rudge.”

“And collect the stuff?”

“Yes. And then make our get-away.”

No program could have outlined more admirably Mr. Twist’s own desires. The mere contemplation of it heartened him. He snatched his glass from the table and drained it with a gesture almost swashbuckling.

“Soapy will have doped the old man by this time, eh?”

“That’s right.”

“But suppose he hasn’t been able to?” said Mr. Twist, with a return of his old nervousness. “Suppose he hasn’t had an opportunity?”

“You can always find an opportunity of doping people. You ought to know that.”

The implied compliment pleased Chimp.

“That’s right,” he chuckled.

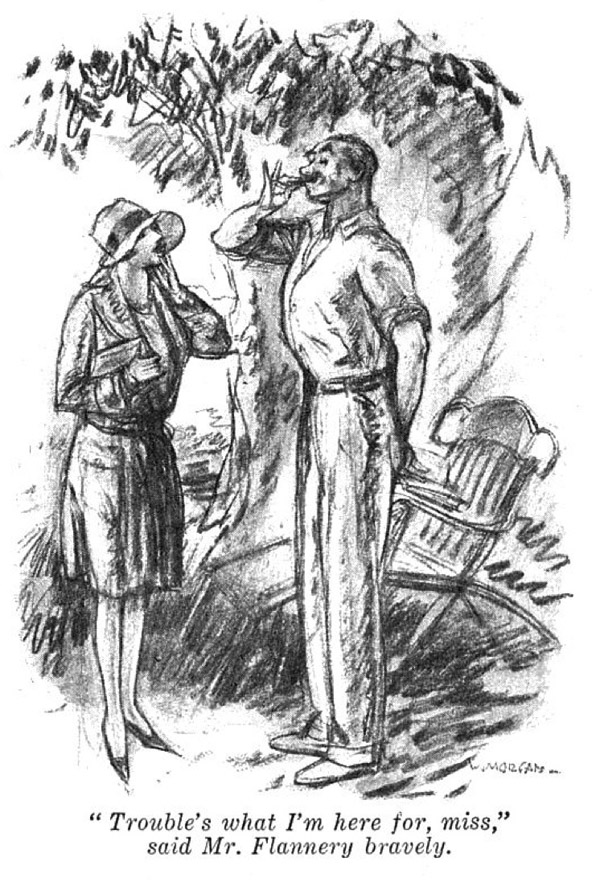

He nodded his head complacently. And immediately something—which may have been an iron girder or possibly the ceiling and the upper parts of the house—seemed to strike him on the base of the skull. He had been standing by the table; and now, crumpling at the knees, he slid gently down to the floor.

Dolly, regarding him, recognized instantly what he had meant just now when he had spoken of John’s appearing like a total loss to his life insurance company. The best you could have said of Alexander Twist at this moment was that he looked peaceful. She drew in her breath a little sharply; and then, being a woman at heart, took a cushion from the armchair and placed it beneath his head.

ONLY then did she go to the telephone and in a gentle voice ask the operator to connect her with Rudge Hall.

“Soapy?”

“Hello!”

The promptitude with which the summons of the bell had been answered brought a smile of approval to her lips. Soapy, she felt, must have been sitting with his hand on the receiver.

“Listen, sweetie.”

“I’m listening, pettie!”

“Everything’s set.”

“Have you fixed that guy?”

“Sure, precious. And Chimp, too.”

“How’s that? Chimp?”

“Sure. We don’t want Chimp around, do we, with that sixty-five thirty-five stuff of his? I just slipped a couple of drops into his highball and he’s gone off as peaceful as a lamb. Say, wait a minute,” she added, as the wire hummed with Mr. Molloy’s low voiced congratulations. “Hello!” she said, returning.

“What were you doing, honey? Did you hear somebody?”

“No. I caught sight of a bunch of lilies in a vase, and I just slipped across and put one of them in Chimp’s hand. Made it seem more sort of natural. Now, listen, Soapy. Everything’s clear for you at your end now, so go right ahead and clean up. I’m going to beat it in that guy Carroll’s runabout, and I haven’t much time, so don’t start talking about the weather or nothing. I’m going to London, to the Belvidere. You collect the stuff and meet me there. Is that all straight?”

“But, pettie!”

“Now what?”

“How am I to get the stuff away?”

“For goodness’ sake! You can drive a car, can’t you? Old Carmody’s car was outside the stable yard when I left. I guess it’s there still. Get the stuff, and then go and tell the chauffeur that old Carmody wants to see him. Then, when he’s gone, climb in and drive to Birmingham. Leave the car outside the station and take a train. That’s simple enough, isn’t it?”

There was a long pause. Admiration seemed to have deprived Mr. Molloy of speech.

“Honey,” he said at length, in a hushed voice, “when it comes to the real smooth stuff you’re there every time. Let me just tell you—”

“All right, baby,” said Dolly. “Save it till later. I’m in a hurry.”

III

SOAPY MOLLOY replaced the receiver and came out of the telephone cupboard glowing with the resolve to go right ahead and clean up as his helpmeet had directed. Like all good husbands, he felt that his wife was an example and an inspiration to him. Mopping his fine forehead—for it had been warm in the cupboard with the door shut—he stood for a while and mused, sketching out in his mind a plan of campaign.

The prudent man, before embarking on any enterprise which may at a moment’s notice necessitate his skipping away from a given spot like a scalded cat, will always begin by preparing his lines of retreat. Mr. Molloy’s first act was to go to the stable yard in order to ascertain with his own eyes that the Dex-Mayo was still there.

It was. It stood out on the gravel, simply waiting for someone to spring to its wheel and be off.

So far, so good. But how far actually was it? The really difficult part of the operations, Mr. Molloy could not but recognize, still lay before him. The knockout drops nestled in his waistcoat pocket all ready for use; but in order to bring about the happy ending it was necessary for him, like some conjuror doing a trick, to transfer them thence to the interior of Mr. Lester Carmody.

And little by little, chilling his enthusiasm, there crept upon Soapy the realization that he had not a notion how the deuce this was to be done.

The whole question of administering knockout drops to a fellow creature is a very delicate and complex one. So much depends on the co-operation of the party of the second part.

Before you can get anything in the nature of action, your victim must first be induced to start drinking something.

At Healthward Ho, Soapy had gathered from the recent telephone conversation, no obstacles had arisen. The thing had been, apparently, from the start, a sort of jolly carousal.

But at Rudge Hall, it was plain, matters were not going to be nearly so simple.

When you are a guest in a man’s house, you cannot very well go about thrusting drinks on your host at half past 11 in the morning.

Probably Mr. Carmody would not think of taking liquid refreshment till lunchtime; and then there would be a butler in and out of the room all the while.

Besides, lunch would not be for another two hours or more, and the whole essence of this enterprise was that it should be put through swiftly and at once.

Mr. Molloy groaned in spirit. He wandered forth into the garden, turning the problem over in his mind with growing desperation, and had just come to the conclusion that he was mentally unequal to it, when, reaching the low wall that bordered the moat, he saw a sight which sent the blood coursing joyously through his veins once more—a sight which made the world a place of sunshine and bird song again.

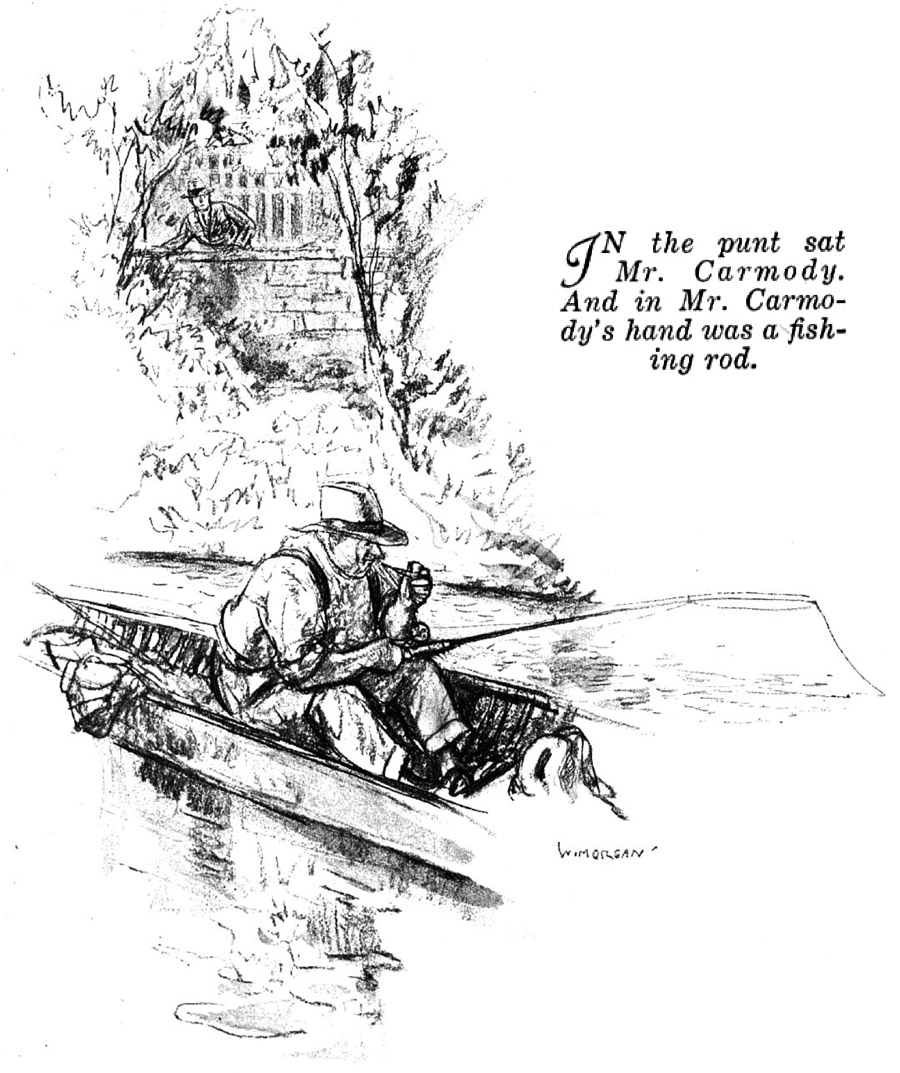

Out in the middle of the moat lay the punt. In the punt sat Mr. Carmody. And in Mr. Carmody’s hand was a fishing rod.

Aesthetically considered, wearing as he did a pink shirt and a slouch hat which should long ago have been given to the deserving poor, Mr. Carmody was not much of a spectacle; but Soapy, eying him, felt that he had never beheld anything lovelier.

HE was not a fisherman himself, but he knew all about fishermen. They became, he was aware, when engaged in their favorite pursuit, virtually monomaniacs.

Earthquakes might occur in their immediate neighborhood, dynasties fall, and pestilences ravage the land, but they would just go on fishing.

As long as the bait held out, Lester Carmody, sitting in that punt, was for all essential purposes as good as if he had been crammed to the brim with the finest knockout drops.

It was as though he were in another world.

Exhilaration filled Soapy like a tonic.

“Any luck?” he shouted.

“Wah, wah, wah,” replied Mr. Carmody inaudibly.

“Stick to it,” cried Soapy. “At-a-boy!”

With an encouraging wave of the hand, he hurried back to the house. The problem which a moment before had seemed to defy solution had now become so simple and easy that a child could have negotiated it—any child, that is to say, capable of holding a hatchet and endowed with sufficient strength to break a cupboard door with it.

A surprise is in store for Soapy. A sudden, overwhelming surprise. Be on hand when he meets it in next week’s installment.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums