Liberty, August 25, 1928

Part Eleven

“I’M telling the birds, telling the bees,” sang Soapy gayly, charging into the hall, “telling the flowers, telling the trees, how I love you—”

“Sir?” said Sturgis respectfully, suddenly becoming manifest out of the infinite.

Soapy gazed at the butler blankly, his wild wood notes dying away in a guttural gurgle. Apart from the embarrassment which always comes upon a man when caught singing, he was feeling, as Sturgis himself would have put it, stottled.

A moment before the place had been completely free from butlers; and where this one could have come from was more than he could understand. Rudge Hall’s old retainer did not look the sort of man who would pop up through traps, but there seemed no other explanation of his presence.

And then, close to the cupboard door, Soapy espied another door, covered with green baize. This, evidently, was the Sturgis bolt hole.

“Nothing,” he said.

“I thought you called, sir.”

“No.”

“Lovely day, sir.”

“Beautiful,” said Soapy.

He gazed bulgily at this inconvenient, old fossil.

Once more shadows had fallen about his world, and he was brooding again on the deep gulf that is fixed between artistic conception and detail work.

The broad artistic conception of breaking open the cupboard door and getting away with the swag while Mr. Carmody, anchored out on the moat, dabbled for bream or dibbled for chub or sniggled for eels, or whatever weak-minded thing it is that fishermen do when left to themselves in the middle of a sheet of water, was magnificent. It was bold, dashing, big in every sense of the word.

Only when you came to inspect it in detail did it occur to you that it might also be a little noisy.

THAT was the fatal flaw—the noise. The more Soapy examined the scheme, the more clearly did he see that it could not be carried through in even comparative quiet. And the very first blow of the hammer or ax or chisel selected for the operation must inevitably bring Methuselah’s little brother popping through that green baize door, full of inquiries.

“Hell!” said Soapy.

“Sir?”

“Nothing,” said Soapy. “I was just thinking.”

He continued to think, and to such effect that before long he had begun to see daylight. There is no doubt that in times of stress the human mind has an odd tendency to take off its coat and roll up its sleeves and generally spread itself in a spasm of unwonted energy.

Probably if this thing had been put up to Mr. Molloy as an academic problem over the nuts and wine after dinner, he would have had to confess himself baffled. Now, however, with such vital issues at stake, it took him but a few minutes to reach the conclusion that what he required, as he could not break open a cupboard door in silence, was some plausible reason for making a noise.

He followed up this line of thought. A noise of smashing wood. In what branch of human activity may a man smash wood blamelessly? The answer was simple. When he is doing carpentering. What sort of carpentering? Why, making something. What? Oh, anything. Yes, but what? Well, say, for example, a rabbit hutch. But why a rabbit hutch? Well, a man might very easily have a daughter who, in her girlish, impulsive way, had decided to keep pet rabbits, mightn’t he? There actually were pet rabbits on the Rudge Hall estate, weren’t there? Certainly there were. Soapy had seen them down at one of the lodges.

The thing began to look good. It only remained to ascertain whether Sturgis was the right recipient for this kind of statement. The world may be divided broadly into two classes—men who will believe you when you suddenly inform them at half past 11 on a summer morning that you propose to start making rabbit hutches, and men who will not. Sturgis looked as if he belonged to the former and far more likable class.

He looked, indeed, like a man who would believe anything.

“Say!” said Soapy.

“Sir?”

“My daughter wants me to make her a rabbit hutch.”

“Indeed, sir?”

Soapy felt relieved. There had been no incredulity in the other’s gaze—on the contrary, something that looked very much like a sort of senile enthusiasm. He had the air of a butler who has heard good news from home.

“Have you got such a thing as a packing case or a sugar box or something like that? And a hatchet?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then fetch them along.”

“Very good, sir.”

The butler disappeared through his green baize door, and Soapy, to fill in the time of waiting, examined the cupboard. It appeared to be a very ordinary sort of cupboard, the kind that a resolute man can open with one well directed blow. Soapy felt complacent. Though primarily a thinker, it pleased him to feel that he could be the man of action when the occasion called.

There was a noise of bumping without. Sturgis reappeared, packing case in one hand, hatchet in the other, looking like Noah taking ship’s stores aboard the Ark.

“Here they are, sir.”

“Thanks.”

“I used to keep roberts when I was a lad, sir,” said the butler. “Oh, dear, yes. Many’s the robert I’ve made a pet of in my time. Roberts and white mice, those were what I was fondest of. And newts in a little aquarium.”

He leaned easily against the wall, beaming; and Soapy, with deep concern, became aware that the Last of the Great Victorians proposed to make this thing a social gathering. He appeared to be regarding Soapy as the nucleus of a salon.

“Don’t let me keep you,” said Soapy.

“You aren’t keeping me, sir,” the butler assured him. “Oh, no, sir, you aren’t keeping me. I’ve done my silver. It will be a pleasure to watch you, sir. Quite likely I can give you a hint or two if you’ve never made a robert hutch before. Many’s the hutch I’ve made in my time. As a lad I was very handy at that sort of thing.”

A DULL despair settled upon Soapy. It was plain to him now that he had unwittingly delivered himself over into the clutches of a bore who had probably been pining away for someone on whom to pour out his wealth of stored up conversation.

Words had begun to flutter out of this butler like bats out of a barn. He had become a sort of human Topical Talk on rabbits. He was speaking of rabbits he had known in his hot youth—their manners, customs, and the amount of lettuce they had consumed per diem.

To a man interested in rabbits, but too lazy to look the subject up in the Encyclopædia, the narrative would have been enthralling. It induced in Soapy a feverishness that touched the skirts of homicidal mania. The thought came into his mind that there are other uses to which a hatchet may be put besides the making of rabbit hutches.

England trembled on the verge of being short one butler.

Sturgis had now become involved in a long story of his early manhood; and even had Soapy been less distrait he might have found it difficult to enjoy it to the full. It was about an acquaintance of his who had kept rabbits, and it suffered in lucidity from his unfortunate habit of pronouncing rabbits “roberts,” combined with the fact that by a singular coincidence the acquaintance had been a Mr. Roberts.

Roberts, it seemed, had been deeply attached to roberts. In fact, his practice of keeping roberts in his bedroom had led to trouble with Mrs. Roberts, and in the end Mrs. Roberts had drowned the roberts in the pond, and Roberts, who thought the world of his roberts and not quite so highly of Mrs. Roberts, had never forgiven her.

Here Sturgis paused, apparently for comment.

“Is that so?” said Soapy, breathing heavily.

“Yes, sir.”

“In the pond?”

“In the pond, sir.”

Like some “Open, sesame,” the word suddenly touched a chord in Soapy’s mind.

“Say, listen,” he said. “All the while we’ve been talking I was forgetting that Mr. Carmody is out there on the pond.”

“The moat, sir?”

“Call it what you like. Anyway, he’s there, fishing, and he told me to tell you to take him out something to drink.”

Immediately Sturgis the lecturer, with a change almost startling in its abruptness, became Sturgis the butler once more. The fanatic rabbit gleam died out of his eyes.

“Very good, sir.”

“You should hurry. His tongue was hanging out when I left him.”

For an instant the butler wavered. The words had recalled to his mind a lop eared doe which he had once owned, whose habit of putting out its tongue and gasping had been the cause of some concern to him in the late ’70s. But he recovered himself.

Registering a mental resolve to seek out this new made friend of his later and put the complete facts before him, he passed through the green baize door.

Soapy, alone at last, did not delay. With all the pent up energy which had been accumulating within him during a quarter of an hour which had seemed a lifetime, he swung the hatchet and brought it down. The panel splintered. The lock snapped. The door swung open.

There was an electric switch inside the cupboard. He pressed it down and was able to see clearly.

And, having seen clearly, he drew back, his lips trembling with half spoken words of the regrettable kind which a man picks up in the course of a lifetime spent in the less refined social circles of New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago.

The cupboard contained an old raincoat, two hats, a rusty golf club, six croquet balls, a pamphlet on stock breeding, three umbrellas, a copy of the Parish Magazine for the preceding November, a shoe, a mouse, and a smell of apples—but no suitcase.

That much Soapy had been able to see in the first awful, disintegrating instant.

No bag, box, portmanteau, or suitcase of any kind or description whatsoever!

HOPE does not readily desert the human breast. After the first numbing impact of any shock, we most of us have a tendency to try to persuade ourselves that things may not be so bad as they seem.

Some explanation, we feel, will be forthcoming shortly, putting the whole matter in a different light. And so, after a few moments during which he stood petrified, muttering some of the comments which on the face of it the situation seemed to demand, Soapy cheered up a little.

He had had, he reflected, no opportunity of private speech with his host this morning. If Mr. Carmody had decided to change his plans and deposit the suitcase in some other hiding place, he might have done so in quite good faith without Soapy’s knowledge. For all he knew, in mentally labeling Mr. Carmody as a fat, popeyed, crooked, swindling, pie faced, double crossing Judas, he might be doing him an injustice. Feeling calmer, though still anxious, he left the house and started toward the moat.

Halfway down the garden he encountered Sturgis, returning with an empty tray.

“You must have misunderstood Mr. Carmody, sir,” said the butler genially, as one rabbit fancier to another. “He says he did not ask for any drink. But he came ashore and had it. If you’re looking for him, you will find him in the boathouse.”

And in the boathouse Mr. Carmody was, lolling at his ease on the cushions of the punt, sipping the contents of a long glass.

“Hullo,” said Mr. Carmody. “There you are.”

Soapy descended the steps. What he had to say was not the kind of thing a prudent man shouts at long range.

“Say!” said Soapy in a cautious undertone. “I’ve been trying to get a word with you all the morning. But that darned policeman was around all the time.”

“Something on your mind?” said Mr. Carmody affably. “I’ve caught two perch, a bream, and a grayling,” he added, finishing the contents of his glass with a good deal of relish.

SUCH was the condition of Soapy’s nervous system that he very nearly damned the perch, the bream, and the grayling, in the order named. But he checked himself in time. If ever, he felt, there was a moment when diplomacy was needed, this was it.

“Listen,” he said. “I’ve been thinking.”

“Yes?”

“I’ve been wondering if, after all, that closet you were going to put the stuff in is a safe place. Somebody might be apt to take a look in it. Maybe,” said Soapy tensely, “that occurred to you?”

“What makes you think that?”

“It just crossed my mind.”

“Oh? I thought perhaps you might have been having a look in that cupboard yourself.”

Soapy moistened his lips, which had become uncomfortably dry.

“But you locked it, surely?” he said.

“Yes, I locked it,” said Mr. Carmody. “But it struck me that, after you had got the butler out of the way by telling him to bring me a drink, you might have thought of breaking the door open.”

IN the silence which followed this devastating remark, there suddenly made itself heard an odd, gurgling noise like a leaking cistern; and Soapy, gazing at his host, was shocked to observe that he had given himself up to an apoplectic spasm of laughter. Mr. Carmody’s rotund body was quivering like a jelly. His eyes were closed, and he was rocking himself to and fro, and from his lips proceeded those hideous sounds of mirth.

The hope which until this moment had been sustaining Soapy had never been a strong, robust hope. From birth it had been an invalid. And now, as he listened to this laughter, the poor, sickly thing coughed quietly and died.

“Oh, dear!” said Mr. Carmody, recovering. “Very funny. Very funny.”

“You think it’s funny, do you?” said Soapy.

“I do,” said Mr. Carmody sincerely. “I wish I could have seen your face when you looked in that cupboard.”

Soapy had nothing to say. He was beaten, crushed, routed, and he knew it. He stared out hopelessly on a bleak world. Outside the boathouse the sun was still shining, but not for Soapy.

“I’ve seen through you all along, my man,” proceeded Mr. Carmody, with ungenerous triumph. “Not from the very beginning, perhaps, because I did suppose for a while you were what you professed to be. The first thing that made me suspicious was when I cabled to New York to make inquiries about a well known financier named Thomas G. Molloy and was informed that no such person existed.”

Soapy did not speak. The bitterness of his meditations precluded words. His eyes were fixed on the trees and flowers on the other side of the water, and he was disliking these very much. Nature had done its best for the scene, and he thought nature a washout.

“And then,” proceeded Mr. Carmody, “I listened outside the study window while you and your friends were having your little discussion. And I heard all I wanted to hear. Next time you hold one of these board meetings of yours, Mr. Molloy, I suggest that you close the window and lower your voices.”

“Yeah?” said Soapy.

It was not, he forced himself to admit, much of a retort, but it was the best he could think of. He was in the depths, and men who are in the depths seldom excel in the matter of rapierlike repartee.

“I thought the matter over, and decided that my best plan was to allow matters to proceed. I was disappointed, of course, to discover that that check of yours for a million or two, or whatever it was, would not be coming my way. But,” said Mr. Carmody philosophically, “there is always the insurance money. It should amount to a nice little sum. Not what a man like you, accustomed to big transactions with Mr. Schwab and Pierpont Morgan, would call much, of course, but quite satisfactory to me.”

“You think so?” said Soapy, goaded to speech. “You think you’re going to clean up on the insurance?”

“I do.”

“Then say, listen, let me tell you something. The insurance company is going to send a fellow down to inquire, isn’t it? Well, what’s to prevent me spilling the beans?”

“I beg your pardon?”

“What’s to keep me from telling him the burglary was a put-up job?”

Mr. Carmody smiled tranquilly.

“Your good sense, I should imagine. How could you make such a story credible without involving yourself in more unpleasantness than I should imagine you would desire? I think I shall be able to rely on you for sympathetic silence, Mr. Molloy.”

“Yeah?”

“I think so.”

And Soapy, reflecting, thought so too. For the process of beans spilling to be enjoyable, he realized, the conditions have to be right.

“I am offering a little reward,” said Mr. Carmody, gently urging the punt out into the open, “just to make everything seem more natural. One thousand pounds is the sum I am proposing to give for the recovery of this stolen property. You had better try for that.

“Well, I must not keep you here all the morning, chattering away like this. No doubt you have much to do.”

The punt floated out into the sunshine, and the roof of the boathouse hid this fat, conscienceless man from Soapy’s eyes. From somewhere out in the great open spaces beyond came the sound of a paddle, wielded with a care-free joyousness. Whatever might be his guest’s state of mind, Mr. Carmody was plainly in the pink.

Soapy climbed the steps listlessly. The interview had left him weak and shaken. He brooded dully on this revelation of the inky depths of Lester Carmody’s soul. It seemed to him that if this was what England’s upper classes (who ought to be setting an example) were like, Great Britain could not hope to continue much longer as a first-class power; and it gave him, in his anguish, a little satisfaction to remember that in years gone by his ancestors had thrown off Britain’s yoke. Beyond burning his eyebrows one Fourth of July, when a boy, he had never thought much about this affair before, but now he was conscious of a glow of patriotic fervor. If General Washington had been present at that moment, Soapy would have shaken hands with him.

II

SOAPY wandered aimlessly through the sunlit garden. He was feeling very low and in urgent need of one of those largely advertised tonics which claim to relieve Anæmia, Brain-Fag, Lassitude, Anxiety, Palpitations, Faintness, Melancholia, Exhaustion, Neurasthenia, Muscular Limpness, and Depression of Spirits. For he had got them all, especially brain-fag and melancholia; and the sudden appearance of Sturgis, fluttering toward him down the gravel path, provided nothing in the nature of a cure.

He felt that he had had all he wanted of the butler’s conversation. He would have fled, but there was nowhere to go. He remained where he was, making his expression as forbidding as possible.

But for the moment, it appeared, Sturgis had put rabbits on one side. Other matters occupied his mind.

“I beg your pardon, sir,” he said, “but have you seen Mr. John?”

“Mr. Who?”

“Mr. John, sir.”

So deep was Soapy’s preoccupation that for a moment the name conveyed nothing to him.

“Mr. Carmody’s nephew, sir. Mr. Carroll.”

“Oh? Yes, he went off in his car with my daughter.”

“Will he be gone long, do you think, sir?”

Soapy could answer that one.

“Yes,” he said. “He won’t be back for some time.”

“You see, when I took Mr. Carmody his drink, sir, he told me to tell Bolt, the chauffeur, to give me the ticket.”

“What ticket?” asked Soapy wearily.

THE butler was only too glad to reply. He had feared that this talk of theirs might be about to end all too quickly, and these explanations helped to prolong it. And now that he knew that there was no need to go on searching for John, his time was his own again.

“It was a ticket for a bag which Mr. Carmody sent Bolt to leave at the cloak room at Shrub Hill station in Worcester this morning, sir. I now ascertain from Bolt that he gave it to Mr. John to give to Mr. Carmody.”

“What!” cried Soapy.

“And Mr. John has apparently gone off without giving it to him. However, no doubt it is quite safe. Did you make satisfactory progress with the hutch, sir?”

“Eh?”

“The robert hutch, sir.”

“What?”

A look of concern came into Sturgis’ face. His companion’s manner was strange.

“Is anything the matter, sir?”

“Eh?”

“Shall I bring you something to drink, sir?”

Few men ever become so distrait that this particular question fails to penetrate. Soapy nodded feverishly. Something to drink was precisely what at this moment he felt he needed most.

Moreover, the process of fetching it would relieve him, for a time at least, of the society of a butler who seemed to combine in equal proportions the outstanding characteristics of a porous plaster and a gadfly.

“Yes,” he replied.

“Very good, sir.”

Soapy’s mind was in a whirl. He could almost feel the brains inside his head heaving and tossing like an angry ocean. So that was what that smooth old crook had done with the stuff—stored it away in a left luggage office at a railway station! If circumstances had been such as to permit of a more impartial and detached attitude of mind, Soapy would have felt for Mr. Carmody’s resource and ingenuity nothing but admiration. A left luggage office was an ideal place in which to store stolen property; as good as the innermost recesses of some safe deposit company’s deepest vault.

But, numerous as were the emotions surging in his bosom, admiration was not one of them. For a while he gave himself up almost entirely to that saddest of mental exercises, the brooding on what might have been. If only he had known that John had the ticket!

But he was a practical man. It was not his way to waste time torturing himself with thoughts of past failures. The future claimed his attention.

What to do?

All, he perceived, was not yet lost. It would be absurd to pretend that things were shaping themselves ideally, but disaster might still be retrieved. It would be embarrassing, no doubt, to meet Chimp Twist after what had occurred, but a man who would win to wealth must learn to put up with embarrassments. The only possible next move was to go over to Healthward Ho, reveal to Chimp what had occurred, and with his co-operation recover the ticket from John.

Soapy brightened. Another possibility had occurred to him. If he were to reach Healthward Ho with the minimum of delay, it might be that he would find both Chimp and John still under the influence of those admirable drops; in which case a man of his resource would surely be able to insinuate himself into John’s presence long enough to be able to remove a left luggage ticket from his person.

But if ’twere done, then ’twere well ’twere done quickly. What he needed was the Dex-Mayo. And the Dex-Mayo was standing outside the stable yard, waiting for him. He became a thing of dash and activity.

As he came panting round the back of the house the first thing he saw was the tail end of the car disappearing into the stable yard.

“HI!” shouted Soapy, using for the purpose the last remains of his breath.

The Dex-Mayo vanished. And Soapy, very nearly a spent force now, arrived at the opening of the stable yard just in time to see Bolt, the chauffeur, putting the key of the garage in his pocket after locking the door.

Bolt was a thing of beauty. He gleamed in the sunshine. He was wearing a new hat, his Sunday clothes, and a pair of yellow shoes that might have been bits chipped off the sun itself. There was a carnation in his buttonhole. He would have lent tone to a garden party at Buckingham Palace.

He regarded Soapy with interest.

“Been having a little run, sir?”

“The car!” croaked Soapy.

“I’ve just put it away, sir. Mr. Carmody has given me the day off to attend the wedding of the wife’s niece over at Upton Snodsbury.”

“I want the car.”

“I’VE just put it away, sir,” said Bolt, speaking more slowly and with the manner of one explaining something to an untutored foreigner. “Mr. Carmody has given me the day off. Mrs. Bolt’s niece is being married over at Upton Snodsbury. And she’s got a lovely day for it,” said the chauffeur, glancing at the sky with something as near approval as a chauffeur ever permits himself.

“Happy the bride that the sun shines on, they say. Not that I agree altogether with these old sayings. I know that when I and Mrs. Bolt was married it rained the whole time like cats and dogs, and we’ve been very happy. Very happy indeed we’ve been, taking it by and large. I don’t say we haven’t had our disagreements, but, taking it one way and another—”

It began to seem to Soapy that the staffs of English country houses must be selected primarily for their powers of conversation. Every domestic with whom he had come in contact at Rudge Hall so far had had at his disposal an apparently endless flow of lively small talk. The butler, if you let him, would gossip all day about rabbits, and here was the chauffeur apparently settling down to dictate his autobiography. And every moment precious!

With a violent effort he contrived to take in a stock of breath.

“I want the car, to go to Healthward Ho. I can drive it.”

The chauffeur’s manner changed. Up till now he had been the cheery clubman meeting an old friend in the smoking room and drawing him aside for a long, intimate chat; but at this shocking suggestion he froze. He gazed at Soapy with horrified incredulity.

“Drive the Dex-Mayo, sir?” he gasped.

“Over to Healthward Ho.”

The crisis passed. Bolt swallowed convulsively and was himself once more. One must be patient, he realized, with laymen. They do not understand.

When they come to a chauffeur and calmly propose that their vile hands shall touch his sacred steering wheel, they are not trying to be deliberately offensive. It is simply that they do not know.

“I’m afraid that wouldn’t quite do, sir,” he said with a faint, reproving smile.

“Do you think I can’t drive?”

“Not the Dex-Mayo you can’t, sir.” Bolt spoke a little curtly, for he had been much moved and was still shaken. “Mr. Carmody don’t like nobody handling his car but me.”

“But I must go over to Healthward Ho. It’s important. Business.”

The chauffeur reflected.

“Well, sir, there’s an old push bike of mine lying in the stables. You could take that if you liked. It’s a little rusty, not having been used for some time, but I dare say it would carry you as far as Healthward Ho.”

Soapy hesitated for a moment. The thought of a twenty mile journey on a machine which he had always supposed to have become obsolete during his knickerbocker days made him quail a little.

Then the thought of his mission lent him strength. He was a desperate man, and desperate men must do desperate things.

“Fetch it out!” he said.

BOLT fetched it out; and Soapy, looking upon it, quailed again.

“Is that it?” he said dully.

“That’s it, sir,” said the chauffeur.

There was only one adjective to describe this push bike—the adjective blackguardly. It had that leering air, shared by some parrots and the baser variety of cat, of having seen and being jauntily familiar with all the sin of the world. It looked low and furtive. Its handlebars curved up instead of down; it had gaps in its spokes; and its pedals were naked and unashamed. A sans-culotte of a bicycle. The sort of bicycle that snaps at strangers.

“H’m!” said Soapy, ruminating.

Then he remembered again how imperative was the need of reaching Healthward Ho somehow.

“All right,” he said, with a shudder.

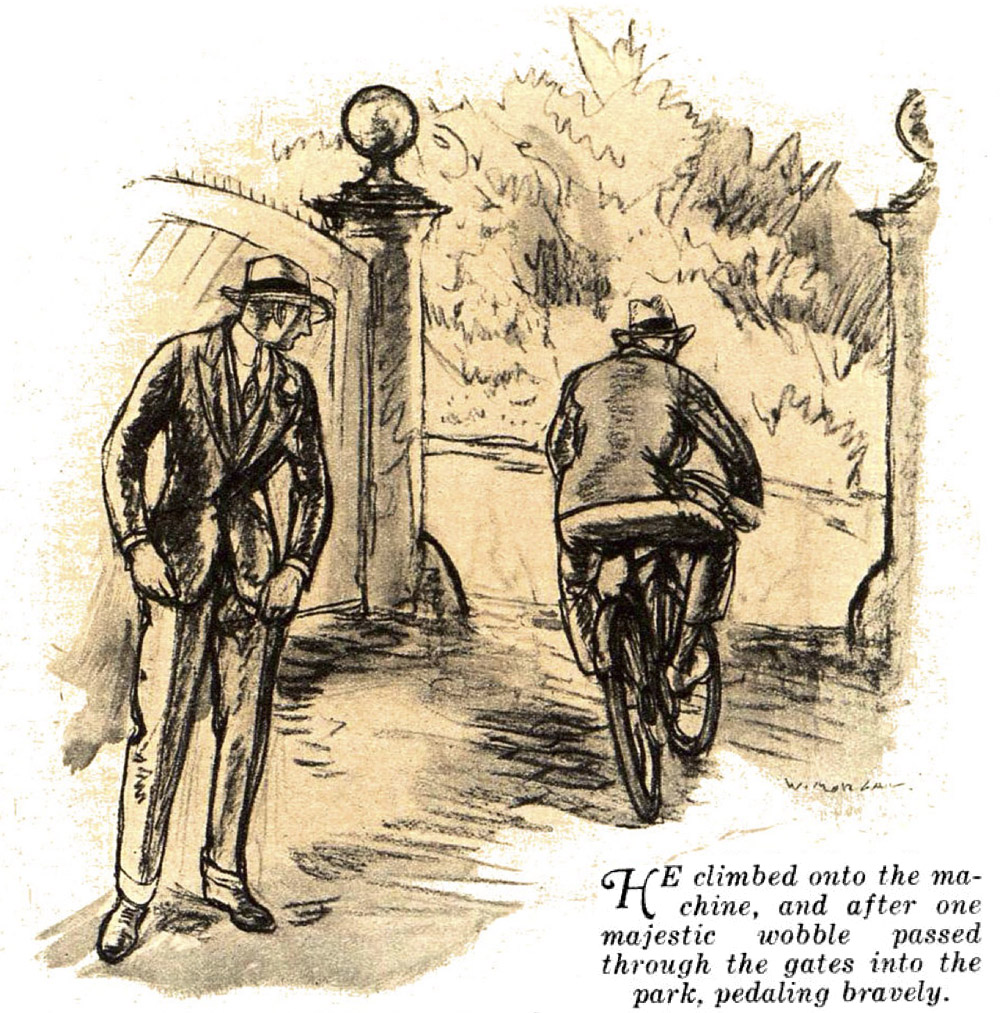

He climbed onto the machine, and after one majestic wobble passed through the gates into the park, pedaling bravely. As he disappeared from view, there floated back to Bolt, standing outside the stable yard, a single agonized “Ouch!”

Chauffeurs do not laugh, but they occasionally smile. Bolt smiled. He had been bitten by that bicycle himself.

III

IT was twenty minutes past 1 that Butler Sturgis, dozing in his pantry, was jerked from slumber by the sound of the telephone bell. He had been hoping for an uninterrupted siesta, for he had had a perplexing and trying morning.

First, on top of the most sensational night of his life, there had been all the nervous excitement of seeing policemen roaming about the place. Then the American gentleman, Mr. Molloy, had told him that Mr. Carmody wanted something to drink, and Mr. Carmody had denied having ordered it. Then Mr. Molloy had asked for a drink himself and had disappeared without waiting to get it. And, finally, there was the matter of the cupboard. Mr. Molloy, after starting to build a rabbit hutch, had apparently suspended operations in favor of smashing in the door of the cupboard at the foot of the stairs. It was all very puzzling to Sturgis; and, like most men of settled habit, he found the process of being puzzled upsetting.

He went to the telephone, and a silver voice came to him over the wire:

“Is this the Hall? I want to speak to Mr. Carroll.”

Sturgis recognized the voice.

“Miss Wyvern?”

“Yes. Is that Sturgis? I say, Sturgis, what has become of Mr. Carroll? I was expecting him here half an hour ago. Have you seen him about anywhere?”

“I have not seen him since shortly after breakfast, miss. I understand that he went off in his little car with Miss Molloy.”

“What!”

“Yes, miss. Some time ago.”

There was silence at the other end of the wire.

“With Miss Molloy?” said the silver voice flatly.

“Yes, miss.”

Silence again.

“Did he say when he would be back?”

“No, miss. But I understand that he was not proposing to return till quite late in the day.”

More silence.

“Oh?”

“Yes, miss. Any message I can give him?”

“No, thank you. . . . No. . . . No, it doesn’t matter.”

“Very good, miss.”

Sturgis returned to his pantry. Pat, hanging up the receiver, went out into her garden. Her face was set, and her lips compressed.

A snail crossed her path. She did not tread on it, for she had a kind heart, but she gave it a look. It was a look which, had it reached John, at whom it was really directed, would have scorched him.

If Pat had known what a strange predicament John was in, at the very moment she scowled at the unoffending snail, she would have been appalled. Read about his troubles in next week’s Liberty.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums