Liberty, June 9, 1928

“CORKY, old horse,” said Stanley Featherstonehaugh Ukridge in a stunned voice, “this is the most amazing thing I have heard in the whole course of my existence. I’m astounded. You could knock me down with a feather.”

“I wish I had one.”

“This suit—this shabby, worn-out suit—you don’t really mean to stand there and tell me that you actually wanted this ragged, seedy, battered old suit? Why, upon my honest Sam, when I came on it while rummaging through your belongings yesterday, I thought it was just something you had discarded years ago and forgotten to give to the deserving poor.”

I spoke my mind. Any unbiased judge would have admitted that I had cause for warmth. Spring, coming to London in a burst of golden sunshine, was calling imperiously to all young men to rejoice in their youth, to put on their new herringbone-pattern lounge suits and go out and give the populace an eyeful: and this I had been prevented from doing by the fact that my new suit had mysteriously disappeared.

After a separation of twenty-four hours, I had just met it in Piccadilly with Ukridge inside it.

I continued to speak, and was beginning to achieve a certain eloquence when from a taxicab beside us there alighted a small, dapper old gentleman who might have been a duke or one of the better-class ambassadors or something of that sort. He wore a pointed white beard, a silk hat, lavender spats, an Ascot tie, and a gardenia; and if anyone had told me that such a man could have even a nodding acquaintance with S. F. Ukridge I should have laughed hollowly. Furthermore, if I had been informed that Ukridge, warmly greeted by such a man, would have ignored him and passed coldly on, I should have declined to believe it.

Nevertheless, both these miracles happened.

“Stanley!” cried the old gentleman. “Bless my soul, I haven’t seen you for years.” And he spoke, what is more, as if he regretted the fact, not as if he had had a bit of luck that made my mouth water. “Come and have some lunch, my dear boy.”

“Corky,” said Ukridge, eying him stonily for a moment and speaking in a low, strained voice, “let us be getting along.”

“But did you hear him?” I gasped as he hurried me away. “He asked you to lunch.”

“I heard him. Corky, old boy,” said Ukridge gravely, “I’ll tell you. That bloke is best avoided.”

“Who is he?”

“An uncle of mine.”

“But he seemed respectable.”

“That is to say, a stepuncle. Or would you call him step-step? He married my late stepmother’s stepsister. I’m not half sure,” said Ukridge, pondering, “that step-step-step wouldn’t be the correct description.”

These were deep waters, into which I was not prepared to plunge.

“But what did you want to cut him for?”

“It’s a long story. I’ll tell you at lunch.”

I raised a passionate hand.

“If you think that after pinching my spring suiting you’re going to get so much as a crust of bread—”

“Calm yourself, laddie. You’re lunching with me. Largely on the strength of this suit, I managed to get past the outer defenses of the Foreign Office just now and touch old George Tupper for a fiver. Joy will be unconfined.”

“CORKY,” said Ukridge, thoughtfully spreading caviar on a piece of toast in the Regent Grillroom some ten minutes later, “do you ever brood on what might have been?”

“I’m doing it now. I might have been wearing that suit.”

“There is no need to go into that again,” said Ukridge with dignity. “I have explained that little misunderstanding—explained it fully. What I mean is, do you ever brood on the inscrutable workings of Fate, and reflect how, but for this or that, you might have been—well, that or this? For instance, but for the old Stepper I would by now be the mainstay of a vast business and in all probability happily married to a charming girl and the father of half a dozen prattling children.”

“In which case, if there is anything in heredity, I should have had to keep my spring suits in a safe deposit.”

“Corky, old horse,” said Ukridge, pained, “you keep harping on this beastly suit of yours. It shows an ungracious spirit which I do not like to see. What was I saying?”

“You were babbling about Fate.”

“Ah, yes.”

FATE [said Ukridge] is odd. Rummy. You can’t say it isn’t. Lots of people have noticed it. And one of the rummiest things about it is the way it seems to take a delight in patting you on the head and lulling you into security and then suddenly steering your foot on to the banana skin. Just when things appear to be going smoothest, bang! comes the spanner into the machinery, and there you are.

Take this business I’m going to tell you about. Just before it happened I had begun to look upon myself as fortune’s favorite child. Everything was breaking right in the most astounding fashion.

My Aunt Julia, having sailed for America on one of her lecturing tours, had lent me her cottage at Market Deeping in Sussex till her return, with instructions to the local tradesmen to let me have the necessaries of life and chalk them up to her. From some source which at the moment I cannot recollect I had snaffled two pairs of white flannel trousers and a tennis racket. And, finally, after a rather painful scene in the course of which I was compelled to allude to him as a pig-headed bureaucrat, I had contrived to get a couple of quid out of old Tuppy.

My position was solid. I ought to have known that luck like that couldn’t last.

Now, in a parting conversation on the platform at Waterloo while waiting for the boat train to start, Aunt Julia had revealed the fact that her motive in sticking me down at her cottage had not been simply to insure that I have a pleasant summer.

It seemed that at Deeping Hall, the big house of the locality, there resided a certain Sir Edward Bayliss, O. B. E., a bird deeply immersed in the jute industry. To this day I have never quite got it clear what jute really is; but, anyway, this Sir Edward was the sort of O. B. E. to keep in with, for his business had ramifications everywhere and endless openings for the bright young man.

He was, moreover, a great admirer of my aunt’s novels; and she told me in a few and, in parts, tactless words that what I was going down there for was to ingratiate myself with him and land a job. Which, she said—and this was where I thought her remarks lacked taste—would give me a chance of doing something useful and ceasing to be what she called a wastrel and an idler.

Idler! Upon my Sam! As if for a single day in my life, Corky, I have ever not buzzed about, doing the work of ten men. Why, take the mere getting of that couple of quid from old Tuppy, for instance. Simple as it sounds, I doubt if Napoleon could have done it. And yet, in less than a quarter of an hour I had got a couple of quid out of him. . . .

Oh, well, women say these things.

Well, I packed a suitcase and took the next train down to Market Deeping. And the first thing for you to do, Corky, before I go on, is to visualize the general layout of the place.

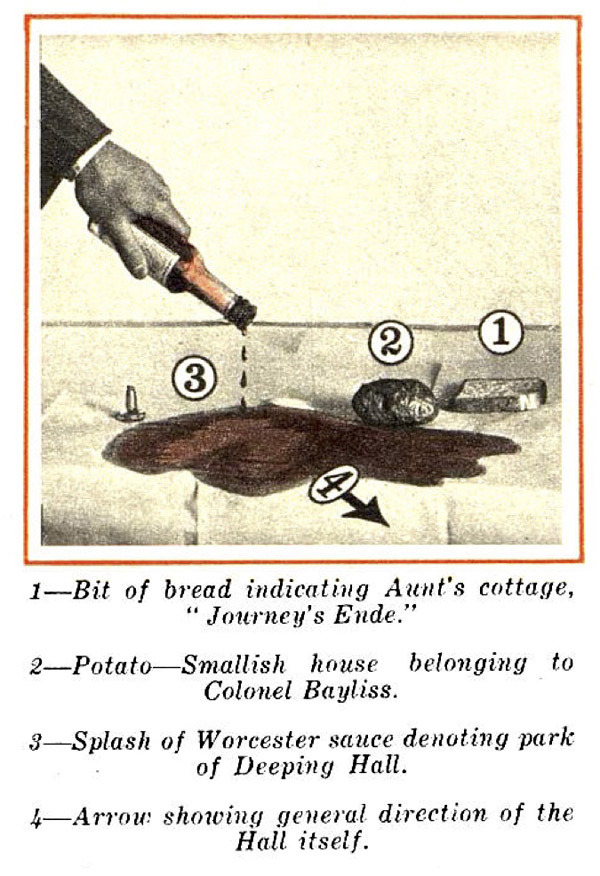

My aunt’s cottage (“Journey’s Ende”) was here where this bit of bread is. Here, next to it, where I’ve put the potato, was a smallish house (“Pondicherry”) belonging to Colonel Bayliss, the jute fancier’s brother. The gardens adjoined, but anything in the way of neighborly fraternizing was prevented for the moment by the fact that the Colonel was away—at Harrogate, I learned later, trying to teach his liver to take a joke. All this expanse here—I’ll mark it with a splash of Worcester sauce—was the park of Deeping Hall, beyond which was the Hall itself and all the gardens, messuages, pleasances, and so forth that you’d expect.

My aunt’s cottage (“Journey’s Ende”) was here where this bit of bread is. Here, next to it, where I’ve put the potato, was a smallish house (“Pondicherry”) belonging to Colonel Bayliss, the jute fancier’s brother. The gardens adjoined, but anything in the way of neighborly fraternizing was prevented for the moment by the fact that the Colonel was away—at Harrogate, I learned later, trying to teach his liver to take a joke. All this expanse here—I’ll mark it with a splash of Worcester sauce—was the park of Deeping Hall, beyond which was the Hall itself and all the gardens, messuages, pleasances, and so forth that you’d expect.

Got it now? Right.

Well, as you can see from the diagram, the park of the Hall abutted—if that’s the word I want—on the back garden of my cottage. And judge of my emotions when, as I smoked an after-breakfast pipe under the trees on the first morning after my arrival, I saw the most extraordinarily pretty girl riding there—hither and thither. She came so close once that I could have hit her with an apple. Not that I did, of course.

I don’t know if you have ever been in love at first sight, Corky? It’s a most peculiar feeling. Like some sort of an explosion. One moment I was looking idly through the hedge to see where the hoof beats came from; the next I was electrified from head to foot, and in the bushes around me a million birds had begun to toot.

I gathered at once that this must be the O. B. E.’s daughter, or something on those lines, and I found my whole attitude toward the jute business, which up till then had been what you might call lukewarm, changing in a flash. It didn’t take me more than a second to realize that a job involving a connection with this girl was practically the ideal one.

I called at the hall that afternoon, mentioning my name, and from the very start everything went like a breeze.

I don’t want to boast, Corky, and of course I’m speaking now of some years ago, before Life had furrowed my brow and given my eyes that haunted look. But I may tell you frankly that at the time when these things happened I was a rather dazzling spectacle.

I had just had my hair cut, and the flannel bags fitted me to a nicety, and altogether I was an asset—yes, old horse, a positive asset to any social circle.

The days flew by. The O. B. E. was chummy. The girl—her name was Myrtle, and I think she had found life at Market Deeping a bit on the slow side till I arrived—always seemed glad to see me. I was the petted neighbor.

And then, one afternoon, in walked the Stepper.

THERE have been occasions in my life, Corky, when, if I had seen a strange man with a white beard walking up the path to the front door of the house where I was living, I would have ducked through the back premises and remained concealed in the raspberry bushes till he had withdrawn. But it so happened that at this time my financial affairs were on a sound and solid basis and I hadn’t a single creditor in the world. So I went down and opened the door and found him beaming on the mat.

“Stanley Ukridge?” he said.

“Yes,” I said.

“I called at your aunt’s house at Wimbledon the other day, and they told me you were here. I’m your Uncle Percy from Australia, my boy. I married your late stepmother’s stepsister Alice.”

I don’t suppose anybody with a pointed white beard has ever received a heartier welcome. I don’t know if you have any pet daydream, Corky, but mine had always been the sudden appearance of the rich uncle from Australia you read so much about in novels—the old-fashioned novels, I mean, the ones where the hero isn’t a dope fiend. And here he was, looking as I had always expected him to look.

You saw his spats just now; you observed his gardenia. Well, on the afternoon of which I’m speaking, he was just as spatted, fully as gardenia-ed, and in addition wore in his tie something that looked like a miniature Koh-i-noor.

“Well, well, well!” I said.

“Well, well, well!” he said.

He patted my back. I patted his. He said he was a lonely old man who had come back to England to spend his declining years with some congenial relative. I said I was just as keen on finding uncles as he was on spotting nephews. The thing was a love feast.

“You can put me up for a week or two, Stanley?”

“Delighted.”

“Nice little place you have here.”

“Glad you like it.”

“Wants a bit of smartening up, though,” said the Stepper, looking round at the appointments and not seeming to think a lot of them. Aunt Julia had furnished the cottage fairly sparsely.

“Perhaps you’re right.”

“Some comfortable chairs, eh?”

“Fine.”

“And a sofa.”

“Splendid.”

“And perhaps a nice little summerhouse for the garden. Have you a summerhouse?”

I said no. No summerhouse.

“I’ll be looking about for one,” said the Stepper.

And everything I had read about rich uncles from Australia seemed to me to have come true. Spacious is the only word to describe his attitude. He was like some Eastern monarch giving the court architect specifications for a new palace. This, I told myself, was how these fine, breezy, empire-building fellows always were—generous, open-handed, gayly reckless of expense. I wished I had met him earlier.

“Must be cozy,” he said.

“Essential.”

“And now, my boy,” said the old Stepper, sticking out from six to eight inches of tongue and running same round his lips, “where do you keep the drinks?”

I’ve always maintained, and I always will maintain, that there’s nothing in this world to beat a real bachelor establishment. Men have a knack of making themselves comfortable which few women can ever achieve. My Aunt Julia’s idea of a chair, for instance, was something antique made to the order of the Spanish Inquisition.

The Stepper had the right conception. Men arrived in vans and unloaded things with slanting backs and cushioned seats, and whenever I wasn’t over at the Hall I wallowed in these.

The Stepper wallowed in them all the time. Occasionally he put in an hour or so in the summerhouse—for he had caused a summerhouse to appear at the bottom of the garden—but mostly you would find him indoors with all the windows shut and something to drink at his elbow. He said he had had so much fresh air in Australia that what he wanted now was something he could scoop out with a spoon.

ONCE or twice I tried to get him over to the Hall, but he would have none of it. He said from what he knew of O. B. E.s he wouldn’t be allowed to take his boots off, and ran, moreover, a grave risk of being offered barley water. Apparently he had once met a teetotal O. B. E. in Sydney and was prejudiced.

However, he was most sympathetic when I told him about Myrtle. He said that, though he wasn’t any too keen on matrimony as an institution, he was broad-minded enough to realize that there might quite possibly be women in the world unlike his late wife. Concerning whom he added that the rabbit was not, as had been generally stated, Australia’s worst pest.

However, he was most sympathetic when I told him about Myrtle. He said that, though he wasn’t any too keen on matrimony as an institution, he was broad-minded enough to realize that there might quite possibly be women in the world unlike his late wife. Concerning whom he added that the rabbit was not, as had been generally stated, Australia’s worst pest.

“Tell me of this girl, my boy,” he said. “You squeeze her a good deal in dark corners, no doubt?”

“Certainly not,” I said stiffly.

“Then things have changed very much since my young days. What do you do?”

I said I looked at her quite a lot and hung on her every word and all that sort of thing.

“Do you give her presents?”

He had touched on a subject which I had intended to bring up myself when I could find an opening. You see, Myrtle’s birthday was approaching, and, though nothing had actually been said about my little gift, I had sensed a certain expectation in the air.

He had touched on a subject which I had intended to bring up myself when I could find an opening. You see, Myrtle’s birthday was approaching, and, though nothing had actually been said about my little gift, I had sensed a certain expectation in the air.

“Even the best of girls are like that, Corky. They say how old they feel with another birthday coming along so soon, and then they look brightly at you.”

“Well, as a matter of fact, Uncle Percy,” I said, flicking a speck of dust off his sleeve, “I was rather planning something of the kind, if only I could see my way to managing it. It’s her birthday next week, Uncle Percy, and it crossed my mind that if I could stumble on somebody who could slip me a few quid, something might possibly be done about it, Uncle Percy.”

He waved his hand in an Australian sort of way.

“Leave it all to me, my boy.”

“Oh, no, really!”

“I insist.”

“Oh—if you insist.”

“My late wife was your late stepmother’s stepsister, and blood is thicker than water. Now, let me see,” mused the old Stepper, wriggling his feet a couple of inches farther on to the table and knitting the brow a bit. “What shall it be? Jewelry? No. Girls like their little bit of jewelry, but perhaps it would scarcely do. I have it. A sundial!”

“A what?” I said.

“A sundial,” said the old Stepper. “What could be a more pretty and tasteful gift? No doubt she has a little garden of her own, some sequestered nook which she tends with her own hands and where she wanders in maiden meditation on summer evenings. If so, she needs a sundial.”

“But, Uncle Percy,” I said doubtfully, “do you really think— My idea was rather that if you could possibly let me have a fiver—or say a tenner to make up the round sum—”

“She draws a sundial,” said the old Stepper firmly, “and likes it.”

I tried to reason with the man.

“But you can’t get a sundial,” I urged.

“I can get a sundial,” said the old Stepper, waving his whisky-and-soda with a good deal of asperity. “I can get anything. Sundials, summerhouses, elephants if you want them. I’m noted for it. Show me the man who says that Charles Percy Cuthbertson can’t get a sundial, and I’ll give him the lie in his teeth. That’s where I’ll give it him. In his teeth!”

And, as he seemed to be warming up a bit, we left it at that. I never dreamed that he would make good, of course. You’ll admit, I think, Corky, that I’m a pretty gifted fellow; but if anyone called upon me at practically a moment’s notice to produce a sundial, I should be nonplused.

Nevertheless, bright and early on the morning of Myrtle’s birthday, I heard a yodel under my window, and there he was, standing beside a wheelbarrow containing one of the nicest sundials I had ever seen. It all seemed to me more like magic than anything, and I began to feel like Aladdin. Apparently my job from now on was simply to rub the lamp and the Stepper would do the rest.

“There you are, my boy,” he said, dusting the thing off with a handkerchief and regarding it in a fatherly sort of way. “You give the little lady that and she’ll let you cuddle her behind the front door.”

This struck a slightly jarring note, of course. He seemed to me to be taking an entirely too earthy view of my great love, which was intensely spiritual. But it was not the moment to say so.

“That’ll make her clap her hands prettily. That’ll send her singing about the house.”

“She ought to like it,” I agreed.

“Of course she’ll like it. She’d better like it. Show me a wholesome, sweet-minded English girl who doesn’t like a sundial and I’ll paste her on the nose,” said the Stepper warmly. “Why, damn it, it’s got a motto and everything.”

And so it had. In Old English letters. Some rot about ye sunne and ye shoures. A really classy sundial.

“I’ll tell you what I was thinking of doing. Uncle Percy,” I said. “How would it be to take this thing over to the Hall this morning and ask Myrtle and her father to tea here? One ought to repay hospitality.”

“Certainly,” said the Stepper. “And I’ll make the house a bower of roses.”

“Can you get roses?”

“Can I get roses! Don’t keep asking me if I can get things. Of course I can get roses. And eggs, too.”

“We shan’t want eggs.”

“We shall want eggs,” said the Stepper, beginning to hot up again. “If eggs are good enough for me, they’re good enough for the popeyed daughter of a blighted O. B. E. Or don’t you think so?”

“Oh, quite, Uncle Percy, quite,” I said.

I would have liked to inform him that Myrtle wasn’t popeyed, but he didn’t seem in the mood.

Any doubts I may have had as to the acceptability of my birthday present vanished as soon as with infinite sweat I had wheeled it across the park in its barrow. The Stepper had had the right idea. Myrtle was all over the sundial.

I sprang the tea invitation, and for a moment it looked as if there was going to be a hitch. Her Uncle Philip, the Colonel, it seemed, was due to materialize that afternoon. He always made a point of being present for his niece’s birthday, however far he had to come to be there; and he would be terribly hurt if he arrived and found she had let him down. What to do?

“Bring him along,” I said, of course. And we arranged it on those lines.

The Colonel, on getting off the train and going to the Hall, would find a note instructing him to hoof it across the park and come and revel at Journey’s Ende.

I didn’t say it to Myrtle, for the time did not seem to me ripe; but what it amounted to, I felt, was that the Colonel would come seeking a niece and would find in addition a nephew. Than which, for a bloke getting on in years and needing all the loved ones round him that could be assembled, what could be a jollier surprise?

I disagree with you, Corky. It does not depend on the kind of nephew. Any nephew is a boon to a lonely bachelor like that.

So I wheeled the wheelbarrow back to the cottage, feeling that all was well. And at about half-past four the maid who came in from the village by the day to do our cooking and washing up announced Sir Edward and Miss Bayliss.

I’M an old campaigner now, Corky, and Fate has to take its coat off and spit on its hands a bit if it wants to fool me. Today, when Fate offers me something gilt edged, I look it over coldly. I assume, till it has been proved otherwise, that attached to it somewhere there is a string. But at the time of which I am speaking I was younger, more buoyant, more credulous; and I honestly supposed that this tea party of mine was going to be the success it seemed at the start.

The thing had got under way without a suspicion of anything in the nature of a disaster. In the first place, the maid had responded to my coaching in the most admirable manner. A simple child of the soil, her natural disposition would have been to bung the door open and bellow, “They’re here!” Instead of which, she had done the announcing with a style and polish that gave the whole proceedings a tone from the very outset.

Secondly, Sir Edward had not bumped his head against the beam on the ceiling just inside the front door.

And lastly, though the Stepper’s roses were present in wonderful profusion, he himself hadn’t shown up. And that seemed to me the biggest stroke of luck of the lot.

You see, the old Stepper wasn’t everybody’s money. To begin with, he had an apparently incurable dislike of O. B. E.s; and then, he combined with a hot-blooded and imperious nature the odd belief that eggs were a suitable food for adult human beings at 5 o’clock in the afternoon. And he was so touchy, too—so ready to resent opposition. I had had visions of him standing over Sir Edward and shoving eggs down his throat at the point of a table knife. He was better away, and I hoped he had fallen into a ditch and couldn’t get out.

FROM the moment the first drop of tea was poured everything went as smooth as oil. In recent years, Corky, affairs have so shaped themselves that you have had the opportunity of seeing me mainly in the capacity of a guest; but you can take it from me that, vouchsafed the right conditions, I can be a very sparkling host. Give me a roof over my head, plenty of buttered toast, and no creditors in sight, and I shine with the best of them.

On the present occasion I was at the top of my form. I handed cups; I slid the toast about; I prattled merrily. And I could see the old boy was impressed. These O. B. E.s are silent, reserved men, and for a while he just looked at me from time to time in a meditative way. Then, as he was dipping into his third cup of tea, out he came into the open and began to talk turkey.

“Your aunt— Have you heard from her, by the way?”

“Not yet. I suppose she’s very busy.”

“I imagine so. An energetic woman.”

“Very. All we Ukridges are energetic. We do not spare ourselves.”

“Your aunt,” resumed the old boy, swallowing some more tea, “gave me the impression, in one of the conversations we had before she left England, that you were looking out for an opening in the world of commerce.”

“Yes,” I said.

I stroked my chin thoughtfully and tried to look as much as possible like Charles M. Schwab being approached by the president of the United States Steel Corporation with a view to a merger. You’ve got to show these birds that you’ve a proper sense of your own value. Start right with them or it’s no use starting at all.

“I might accept commercial employment if the salary and prospects were undeniable.”

He cleared his throat.

“In my own business,” he was beginning, “the jute business—”

Just then the door opened and the maid appeared. She was one of those snorting girls, and she snorted something about a gentleman. I couldn’t get it.

“Who’s a gentleman?” I said.

“Outside. He says he wants to see you.”

“It must be Uncle Philip,” said Myrtle.

“Of course,” I said. “Show him in. Don’t keep him waiting, my good girl. Show him in at once.”

And a moment later in came a massive bloke with large eyebrows and a sort of look about him that made you feel he believed in infant damnation. Obviously not the Colonel, for Myrtle and the O. B. E. gave no sign of recognition. Then who? The man was a perfect stranger to me.

However, I flattered myself I could play the host.

“Good afternoon,” I said affably.

“Afternoon,” said the bloke.

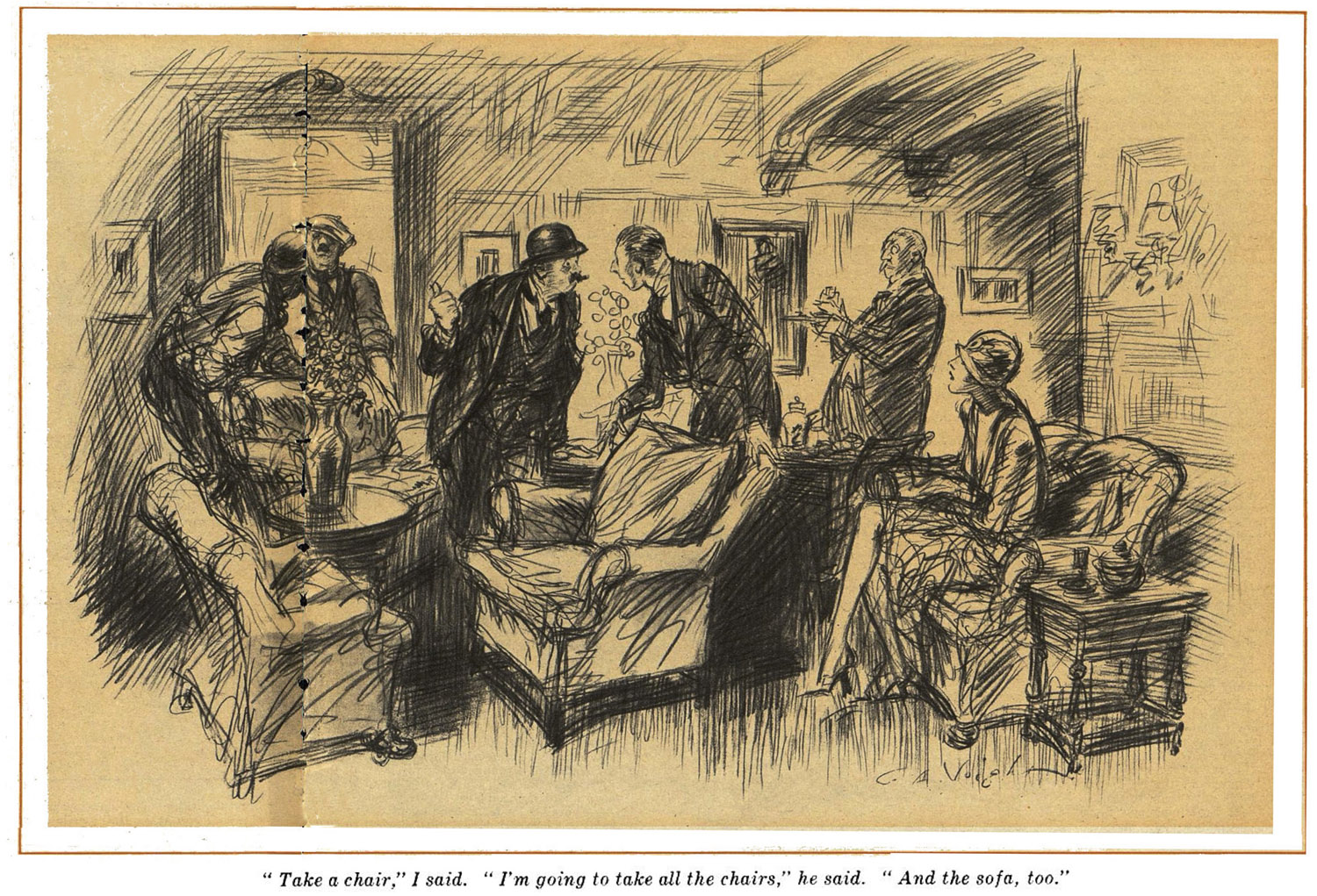

“Take a chair,” I said.

“I’m going to take all the chairs,” he said. “And the sofa, too. I’m from the Mammoth Furnishing Company, and the check for the deposit on this stuff has been returned ‘Refer to drawer.’ ”

IT is not too much to say, Corky, that I reeled. Yes, laddie, your old friend tottered and would have fallen had he not clutched at a chair. And, from the look in the bloke’s eye, it began to seem that my chances of clutching at that particular chair were likely to be very soon a thing of the past.

He had one of those brooding eyes—two probably, only there was a patch over the left one. I think someone must have hit him there. A fellow like that could scarcely go through life for long without getting punched in the eye.

“But, my dear old horse—” I began.

“It’s no use arguing. We’ve written twice and never got an answer, and I’ve instructions from the firm to take the stuff.”

“But we’re using it.”

“Not now,” said the blighter. “You’ve finished.”

I look back on that moment, Corky, old boy, as one of the worst in my career. It is always a nervous business for a fellow to entertain for the first time the girl he loves and her father. And, believe me, it doesn’t help pass things off when a couple of the proletariat in shirt sleeves surge into the room and start carrying out all the chairs. Conversation during the proceedings was, you might say, at a standstill; and even after the operations were over it wasn’t any too easy to get it going again.

“Some absurd mistake,” I said.

“No doubt,” said the O. B. E.

“I shall write those people a very stiff letter tonight.”

“No doubt.”

“That furniture was bought by my uncle, one of the wealthiest men in Australia. It’s absurd to suppose that a man of standing would—”

“No doubt. Myrtle, my dear, I think we will be going.”

Then, Corky, I spread myself. On not a few occasions in a life that has had its ups and downs I have been compelled to do some impressive talking. But now I surpassed all previous efforts.

THE thought of all that was slipping away from me spurred me to heights I have never reached before or since. And gradually, little by little, I made headway.

The old boy tried to shake me off and edge through the French windows; but it is pretty hard to shake me off when I am at my best. I grabbed him by the buttonhole and steered him back into the room. And when, in a dazed sort of way, he reached out and took a slice of cake, I knew the battle was won.

“The way I look at it is this,” I said, getting between him and the window. “A man like my uncle would no doubt have a number of accounts in different banks. The one on which he drew this check happened to have insufficient funds in it, and the bank manager, with gross discourtesy—”

“Well, yes, possibly.”

“I shall tell my uncle of what has occurred.”

At this moment somebody behind me said, “Ha!” or it may have been “Ho!”—and I spun round and there in the French window was standing another perfect stranger.

This new addition to our little party was a long, lean, Anglo-Indian-looking individual. You know the type. Beige as to general color scheme and rather like a vulture with a white mustache.

“Uncle Philip!” cried Myrtle.

The Vulture gave a kind of nod in her direction. He seemed upset about something.

“Don’t talk to me,” he said. “I haven’t time. Many happy returns of the day and so forth, but don’t talk to me now, child. There’s the man I want to talk to.”

“You know Mr. Ukridge?”

“No, I don’t. And I don’t want to. But I know he’s stolen—”

He broke off with a hideous rattle in his voice, and I saw that he was staring at the table. It belonged to my aunt and was the only thing in the room that the shirt-sleeved birds had left, so it was fairly conspicuous.

“Good God!” he said.

He switched an eye round and let it play on me like an oxyacetylene blowpipe. I don’t know what the treatment for liver is at Harrogate, but they ought to change it. It’s ineffective. It had obviously done this man no good at all.

“Good God!” he said again.

The O. B. E. came to the surface.

“What’s the matter, Philip?” he asked, annoyed. He had only just finished coughing, having swallowed a bit of cake the wrong way.

“I’LL tell you what’s the matter. I was in my garden just now, and I found it looted—looted! That man there has stripped it of every rose I possess. My roses! The place is a desert.”

“Is this true, Mr. Ukridge?” asked the O. B. E.

“Certainly not,” I said.

“Oh, it isn’t?” said the Vulture. “It isn’t, eh? Then where did those roses come from? There aren’t any rose trees in the garden of this house. Damn it, I’ve been here half a dozen times and I ought to know. Where did you get those roses? Answer me that.”

“My uncle gave them to me.”

The O. B. E., having now disposed of the cake, uttered a nasty laugh.

“Your uncle!” he said.

“What uncle?” cried the Vulture.

“Where’s this uncle? Show me this uncle. Produce him!”

“I’m afraid it would be a little difficult to do that, Philip,” said the O. B. E., and I didn’t at all like his manner. “It appears that Mr. Ukridge possesses a mysterious uncle. Nobody has ever set eyes on him, but it would seem that he buys furniture and does not pay for it, steals roses—”

“And sundials,” put in the Vulture.

“Sundials?”

“That’s what I said. After I’d had a look at my garden I went over to the Hall, and there in the middle of the lawn was my sundial. They told me this fellow here had given it to Myrtle.”

I wasn’t in any too good shape by this time, but I collected enough of the old manly spirit to come back at him.

“How do you know it was your sundial?” I said.

“Because it had my motto on it. And, as if that wasn’t enough, he’s stolen my summerhouse!”

The O. B. E. gulped.

“Your summerhouse?” he said in a low, almost reverent voice. The spaciousness of the thing seemed to have affected his vocal cords. “How could he have stolen a summerhouse?”

“I don’t know how he did it. In sections, I suppose. It’s one of those portable summerhouses. I had it sent down from the Stores last month. And there it is, standing at the bottom of his garden. I tell you, the man ought not to be at large. He’s a menace. Good God! When I was in France during the war a platoon of Australians scrounged one of my cast-iron sheds one night, but I never expected that that sort of thing happened in England in peacetime.”

Corky, a sudden bright light shone on me. I saw all. It was that word “scrounge” that did it. I remembered now having heard of Australia and its scroungers. They go about pinching things, Corky. No, I do not mean spring suits; I mean things that really matter—things of vital import, like sundials and summerhouses: not beastly spring suits, which nobody could tell you wanted, anyway, and you’ll get it back tomorrow as good as new. . . .

Well, be that as it may, I saw all.

“Sir Edward,” I said, “let me explain. My uncle—”

But it was no use, Corky. They wouldn’t listen. The O. B. E. gave me one look, the Vulture gave me another, and I rather fancy Myrtle gave me a third; and then they pushed off and I was alone.

I went over to the table and helped myself to a bit of cold buttered toast, a broken man.

About ten minutes later there was a sound of cheery whistling outside and the Stepper walked in.

“Here I am, my boy,” said the Stepper. “I’ve got the eggs.” And he began shedding them out of every pocket. It looked as if he had been looting every henroost in the neighborhood. “Where are our guests?”

“Gone.”

“Gone?”

He looked round.

“Hullo! Where’s the furniture?”

“Gone.”

“Gone?”

I explained.

“Tut, tut!” said the Stepper.

I sniffed a bit.

“Don’t make sniffing noises at me, my boy,” said the Stepper reprovingly. “The best of men have checks returned from time to time.”

“And I suppose the best of men sneak eggs and roses and sundials and summerhouses?” I said. And I spoke bitterly, Corky.

“Eh?” said the Stepper. “You don’t mean to say—”

“I certainly do.”

“Tell me all.”

I told him all.

“TOO bad!” he said. “I never have been able to shake off this habit of scrounging. Wherever Charles Percy Cuthbertson is, there he scrounges. But who would have supposed that people would make a fuss about a little thing like that? I’m disappointed in the old country. Why, nobody in Australia minds a little scrounging. What’s mine is yours and what’s yours is mine—that’s our motto out there. All this to-do about a sundial and a summerhouse! Why, bless my soul, I’ve scrounged a tennis lawn in my time. Oh, well, there’s nothing to be done about it, I suppose.”

“There’s a lot to be done about it!” I said. “The O. B. E. doesn’t believe I’ve got an uncle. He thinks I pinched all those things myself.”

“Does he?” said the Stepper thoughtfully. “Does he, indeed?”

“And the least you can do is to go up to the Hall and explain.”

“Precisely what I was about to suggest myself. I’ll walk over now and put everything right. Trust me, my boy. I’ll soon fix things up.”

And he trotted out. And that, Corky, is the last I ever saw of him till today.

It’s my belief he never went anywhere near the Hall. I am convinced that he walked straight to the station, no doubt pocketing a couple of telegraph poles and a five-barred gate or so on the way, and took the next train to London.

Certainly there was nothing in the O. B. E.’s manner, when I met him next day in the village, to suggest that everything had been put right and things fixed up. I don’t suppose a jute merchant has ever cut anybody so thoroughly.

And that’s why I wish to impress it upon you, Corky, that that snaky and conscienceless old Stepper is best avoided. No matter how glittering the prospects he may hold out, I say to you—shun him!

Looking at the thing in one way, taking the short, narrow view, I am out a lunch—possibly a good lunch. But do I regret? No. Who knows but that a man like that would have been called to the telephone at the eleventh hour, leaving me stuck with the bill?

And even supposing he really has got money now—how did he get it? That is the question.

I shall make inquiries; and if I find that someone has pinched the Albert Memorial, I shall know what to think!

THE END

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums