London Magazine, May 1927

I AM writing these few words in my hotel bed-room at that delightful French seashore resort, Le Touquet. The hour is two of a fine summer morning, and for the last thirty minutes the man in the room above has been hammering patiently on the floor. The noise of my typewriter apparently keeps him awake. Serve him right. If he were half a sport, he would be down at the Casino, losing his money like an officer and a gentleman, the same as the rest of us boys. What right has he to waste in hoggish slumber the hours that might be devoted to disciplining his soul and forming his character in the Salle de Baccarat?

For there is no doubt about it, this game of baccarat acts on the soul like catnip on a cat. Whether you win or lose, it just takes the soul and makes it jump through hoops. It gives a new meaning to life.

Take my case for example. I have just tottered home after two hours’ feverish fluctuation of fortune, a loser to the extent of some ten pounds; and upon me there has descended a great solemnity—not exactly a divine despair, but rather a consciousness that life is stern and earnest. I have given up the game, of course, for ever, just as I gave up golf this afternoon after missing that eighteen-inch putt at the final hole; but I am a better, finer man for having played it. I feel now that I have definitely put my careless youth behind me, and to-morrow I start shaping out a new life and trying to make a mark in the world. I have done with frivolities. To-morrow I begin reading the five-foot shelf of Classics and doing good to others.

THAT is how losing at baccarat inevitably takes the man of sensibility, and that is why, if I had a son, I would say to him, “James (or Rollo), you are a young man starting life. The Casino is half a mile down the road, to the right as you leave the hotel. Grab all the loose change you can lay hands on, call a taxi, and have a pop at it. And keep on popping till you are down to your last five-franc counter. Then, if you cannot persuade the management to cash a cheque, and there is no one around who looks good for a touch, come home, my boy, and may a father’s blessing help you to shape that new career which will automatically open out before you.”

If I had my way, there should not be a youth in our fair country who had not been skinned to the bone at this game of games.

It is a moot point, however, whether the soul does not expand even more gloriously under the stimulus of winning at baccarat. There is an almost holy satisfaction in changing your counters and coming away laden down with wealth for which you have not had to work.

Moralists may talk of the joys of receiving an honest wage for honest labour, but these cannot be compared with those which come from repeatedly “standing pat” on a five, and seeing the banker floundering miserably with three wretched court cards.

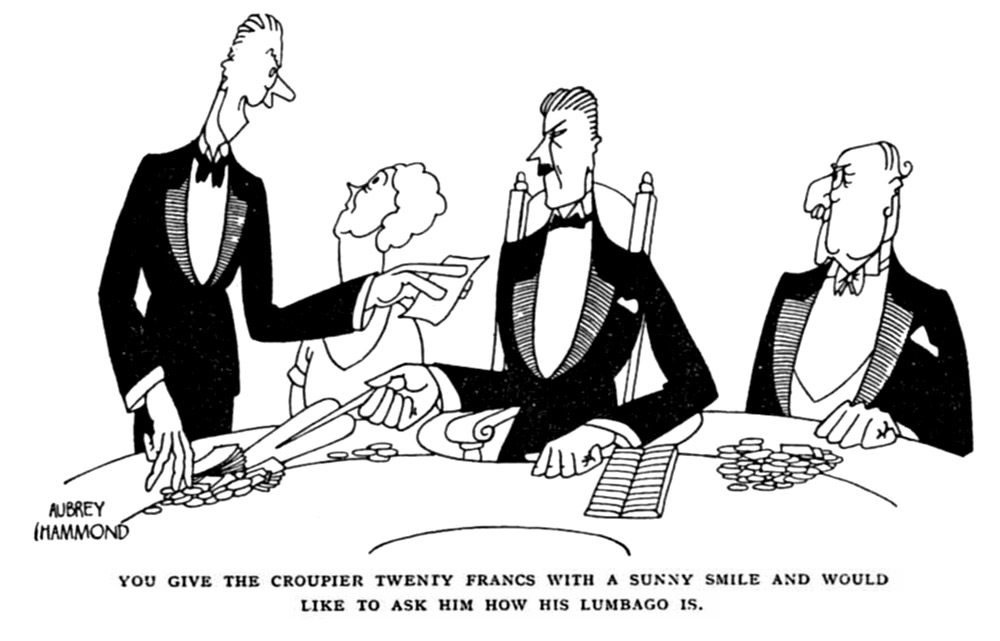

A general winning a great battle may feel a faint shadow of this emotion, and a sort of suggestion of it possibly came to Milton when he wrote “Finis” at the end of “Paradise Lost”; but in few other ways can it be achieved. You feel not only clever but curiously good, as if you had done some great work for humanity and were about to receive the thanks of a grateful nation. You thrill with a universal benevolence. You give the croupier twenty francs with a sunny smile and would like to ask him if they are all well at home and how his lumbago is.

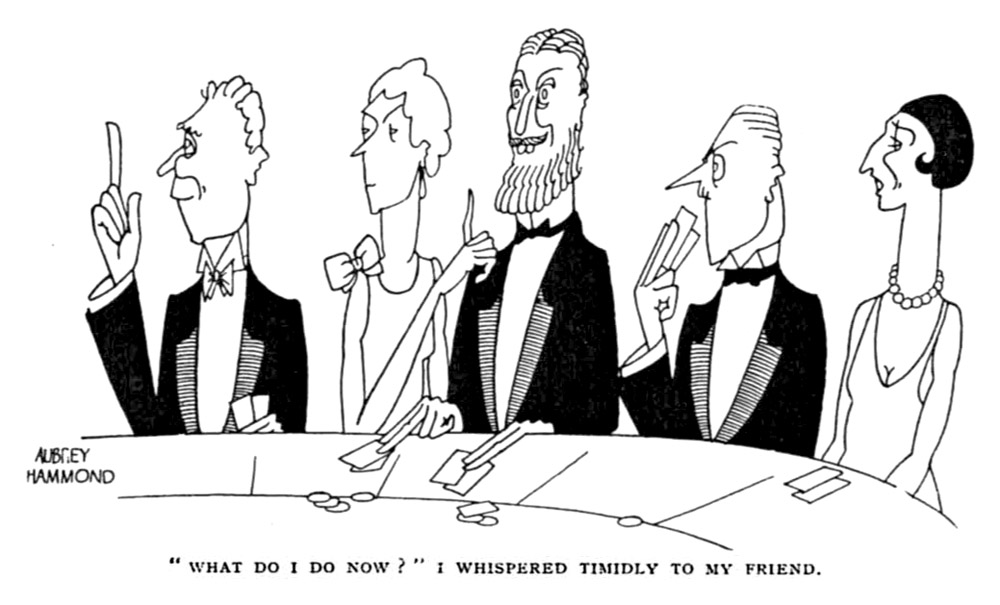

Unfortunately, by a curious law of fortune, the drawback is that you only win the first time you try your hand at the game, knowing nothing about it. How well I remember my initiation into the pastime, the evening when a kindly friend led me to the table and I sat blushfully at his side, wondering what it was all about. The ritual seemed meaningless to me. All round the board clustered Frenchmen (and French women) of varying degrees of homeliness, some with spade-shaped beards, all goggling with the tensity of city-visiting rustics watching their first traffic accident. A stern-faced gentleman of military aspect in the centre pushed a large shoe-shaped arrangement to the man on the left.

“What do I do now?” I whispered timidly to my friend.

“He gives you two cards,” he replied.

I received the two cards.

“What do I do next?” I queried.

“You ask for another,” said my friend, having examined them.

This pleased me. I like to get all that is coming to me. The two cards I had received were a king and a queen, which seemed to me a darned fine start for a beginner. The shoe-man pushed me another. It was a nine. Not so good, I thought.

“What do I do now?” I said.

“You win,” replied my counsellor, and, sure enough, the military person snatched up a large, flat sword and a shower of pink counters shot off the blade in my direction. What I had done to deserve this I could not understand, but it seemed all right as far as the company were concerned, so I decided to let the thing go on, with the result that in twenty minutes I was practically snowed under with counters of all colours.

“What do I do now?” I asked.

“You go home,” said my friend.

Which I did.

How different it is to-day. I know all about it now. I am the man you see on the croupier’s left, watching the board with eyes like gimlets, waving aside some upstart farther down the table with a curt, “Banco prime,” and snapping a chilly, “Carte!” out of the corner of my mouth. When the bank has swelled to vast proportions and all the other faint-hearts are running to cover with bad attacks of cold feet, whose is that manly voice shouting “Banco!”? Mine.

AND yet—why, I cannot say—nothing ever goes right with me now. I have tried smoking while playing; I have tried sitting with a dead cigar in my mouth, petulantly refusing offers of a light; I have tried wearing my new evening shoes and my old evening shoes; I have tried brushing my hair, such as it is, from left to right instead of from right to left; but nothing seems to work. All round me are poor dumb-bells whispering to friends, “What do I do now?” and scooping in the wealth, but I, the expert, get cleaned out every time. It is one of those things you cannot explain. You just have to accept it.

And yet, as I endeavoured to make plain at the beginning of this treatise, I am not grumbling. After all, money is not everything. There are things money cannot buy, and one of them is that wonderful sensation of having passed through the furnace which comes from losing a few pounds at baccarat. How futile and contemptible they seem as you rise from the table a busted man—all these callow fools grinning over their petty gains. You do not know which you despise the most: the fellow with a face like a fish, who has just put up a miserable three louis for his bank, or the blighter with the walrus moustache who tries vainly to conceal his delight, poor simp, at having done him down by a pip. You feel purified and apart, dignified and above all this silliness.

I SHOULD imagine Job must have felt much the same, or St. Simeon Stylites. Clear vision descends upon you. You get a true sense of values. These wretched people with their pitiful winnings! What does it all amount to? At the most a few pounds, which will go in tips to hotel waiters. That is what they will get out of their evening. Whereas you . . . Well, you have got it all mapped out what you are going to do.

You are going to start in to-morrow bright and early studying that Efficiency Course you saw advertised in the magazine. You are going so to train yourself that you will be able to look the boss in the eye and make him wilt. A year from now people will be asking your opinion, as an established authority, of the works of Artbashiekeff. Most probably you will become Prime Minister, and that grinning chump who has just let his bank run on six times and scooped in four thousand francs will be hanging round Downing Street wanting to shake your hand.

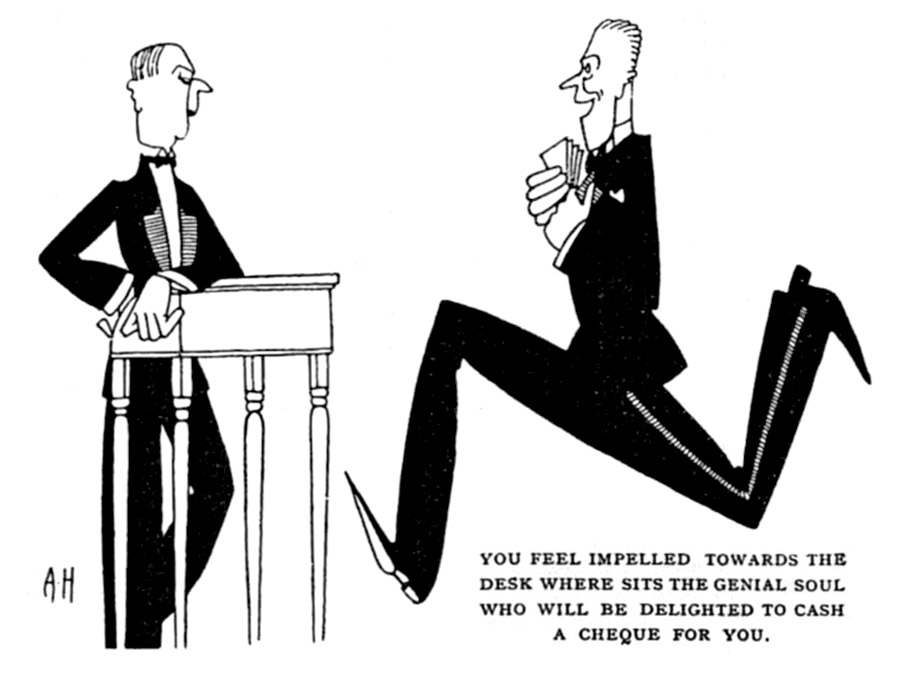

AT this point in your meditations you suddenly find yourself drifting, as if impelled by some mysterious power, towards the desk in the corner where sits the genial soul who will be delighted to cash a cheque for you. . . .

Ah well! No sense in leaving as early as this. You can become Prime Minister just as easily if you get your hooks on another thousand francs and strike a winning streak. A moment later you are striding back to the tables like a leopard stalking its prey. “Donnez moi douze plaques, s’il vous plaît,” you say in your musical patois to the changer. . . .

Now, then! Come along! How much in the bank? Fifty louis, and everyone running for shelter? It would take more than that to scare you. “Banco!”

You can’t keep a good man down.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums