Public School Magazine, January 1902

“WHERE have I seen that face before?” said a voice. Tony Graham looked up from the bag in which he was rummaging.

“Hullo, Allen,” he said, “what the dickens are you up here for?”

“I was rather thinking of doing a little boxing. If you’ve no objection, of course.”

“But you ought to be on a bed of sickness, and that sort of thing. I heard you’d crocked yourself.”

“So I did. Nothing much, though. Trod on myself during a game of fives, and twisted my ankle a bit.”

“In for the middles, of course?”

“Yes.”

“So am I.”

“Yes, so I saw in the Sportsman. It says you weigh eleven-three.”

“Bit more, really, I believe. Shan’t be able to have any lunch probably, or I shall have to go in for the heavies. What are you?”

“Just eleven. Well, let’s hope we meet in the final.”

“Rather,” said Tony.

It was at Aldershot—to be more exact, in the dressing-room of the Queen’s Road Gymnasium at Aldershot—that the conversation took place. From East and West, and North and South, from Dan even unto Beersheba, the representatives of the Public Schools had assembled to box, fence, and perform gymnastic prodigies for fame and silver medals. The room was full of all sorts and sizes of them, heavy-weights looking ponderous and muscular, feather-weights diminutive but wiry, light-weights, middle-weights, fencers, and gymnasts in scores, some wearing the unmistakable air of the veteran, for whom Aldershot has no mysteries, others nervous, and wishing themselves back again at school.

Tony Graham had chosen a corner near the door. This was his first appearance at Aldershot. St. Austin’s was his School, and he was by far the best middle-weight there. But his doubts as to his ability to hold his own against all-comers were extreme, nor were they lessened by the knowledge that his cousin, Allen Thomson, was to be one of his opponents. Indeed, if he had not been a man of mettle, he might well have thought that with Allen’s advent his chances were at an end.

Allen was at Rugby. He was the son of a baronet who owned many acres in Wiltshire and held fixed opinions on the subject of the whole duty of man, who, he held, should be before anything else a sportsman. Both the Thomsons—Allen’s brother Jim was at St. Austin’s in the same House as Tony—were good at most forms of sport. Jim, however, had never taken to the art of boxing very kindly, but, by way of compensation, Allen had skill enough for two. He was a splendid boxer, quick, neat, scientific. He had been up to Aldershot three times, once as a feather-weight and twice as a light-weight, and each time he had returned with the silver medal.

As for Tony, he was more a fighter than a sparrer. When he paid a visit to his uncle’s house he boxed with Allen daily, and invariably got the worst of it. Allen was too quick for him. But he was clever with his hands. His supply of pluck was inexhaustible, and physically he was as hard as nails.

“Is your ankle all right again now?” he asked.

“Pretty well. It wasn’t much of a sprain. Interfered with my training a good bit, though. I ought by rights to be well under eleven stone. You’re all right, I suppose?”

“Not bad. Boxing takes it out of you more than footer or a race. I was in good footer training long before I started to get fit for Aldershot. But I think I ought to get along fairly well. Any idea who’s in against us?”

“Harrow, Felsted, Wellington. That’s all, I think.”

“St. Paul’s?”

“No.”

“Good. Well, I hope your first man mops you up. I’ve a conscientious objection to milling with you.”

Allen laughed. “You’d be all right,” he said, “if you weren’t so beastly slow with your guard. Why don’t you wake up? You hit like blazes.”

“I think I shall start guarding two seconds before you lead. By the way, don’t have any false delicacy about spoiling my aristocratic features. On the ground of relationship, you know.”

“Rather not. Let auld acquaintance be forgot. I’m not Thomson for the present. I’m Rugby.”

“Just so, and I’m St. Austin’s. Personally, I’m going for the knock-out. You won’t feel hurt?”

This was in the days before the Head Master’s conference had abolished the knock-out blow, and a boxer might still pay attentions to the point of his opponent’s jaw with an easy conscience.

“I probably shall if it comes off,” said Allen. “I say, it occurs to me that we shall be weighing-in in a couple of minutes, and I haven’t started to change yet. Good, I’ve not brought evening dress or somebody else’s footer clothes, as usually happens on these festive occasions.”

He was just pulling on his last boot when a Gymnasium official appeared in the doorway.

“Will all those who are entering for the boxing get ready for the weighing-in, please?” he said, and a general exodus ensued.

The weighing-in at the Public Schools’ Boxing Competition is something in the nature of a religious ceremony, but even religious ceremonies come to an end, and after a quarter of an hour or so Tony was weighed in the balance and found correct. He strolled off on a tour of inspection.

After a time he lighted upon the St. Austin’s Gym Instructor, whom he had not seen since they had parted that morning, the one on his way to the dressing-room, the other to the refreshment-bar for a modest quencher.

“Well, Mr. Graham?”

“Hullo, Dawkins. What time does this show start? Do you know when the middle-weights come on?”

“Well, you can’t say for certain. They may keep ’em back a bit or they may make a start with ’em first thing. No, the light-weights are going to start. What number did you draw, sir?”

“One.”

“Then you’ll be in the first middle-weight pair. That’ll be after these two gentlemen.”

“These two gentlemen,” the first of the light-weights, were by this time in the middle of a warmish opening round. Tony watched them with interest and envy. “How beastly nippy they are,” he said.

“Wish I could duck like that,” he added.

“Well, the ’ole thing there is you ’ave to watch the other man’s eyes. But light-weights is always quicker at the duck than what heavier men are. You get the best boxing in the light-weights, though the feathers spar quicker.”

Soon afterwards the contest finished, amidst volleys of applause. It had been a spirited battle, and an exceedingly close thing. The umpires disagreed. After a short consultation, the referee gave it as his opinion that on the whole R. Cloverdale, of Bedford, had had a shade the worse of the exchanges, and that in consequence J. Robinson, of St. Paul’s, was the victor. This was what he meant. What he said was, “Robinson wins,” in a sharp voice, as if somebody were arguing about it. The pair then shook hands and retired.

“First bout, middle-weights,” shrilled the M.C. “W. P. Ross (Wellington) and A. C. R. Graham (St. Austin’s).”

Tony and his opponent retired for a moment to the changing-room, and then made their way amidst applause on to the raised stage on which the ring was pitched. Mr. W. P. Ross proceeded to the farther corner of the ring, where he sat down and was vigorously massaged by his two seconds. Tony took the opposite corner and submitted himself to the same process. It is a very cheering thing at any time to have one’s arms and legs kneaded like bread, and it is especially pleasant if one is at all nervous. It sends a glow through the entire frame. Like somebody’s something it is both grateful and comforting.

Tony’s seconds were curious specimens of humanity. One was a gigantic soldier, very gruff and taciturn, and with decided leanings towards pessimism. The other was also a soldier. He was in every way his colleague’s opposite. He was half his size, had red hair, and was bubbling over with conversation. The other could not interfere with his hair or his size, but he could with his conversation, and whenever he attempted a remark, he was promptly silenced, much to his disgust.

“Plenty o’ moosle ’ere, Fred,” he began, as he rubbed Tony’s left arm.

“Moosle ain’t everything,” said the other, gloomily, and there was silence again.

“Are you ready? Seconds away,” said the referee.

“Time!”

The two stood up to one another.

The Wellington representative was a plucky boxer, but he was not in the same class as Tony. After a few exchanges, the latter got to work, and after that there was only one man in the ring. In the middle of the second round the referee stopped the fight, and gave it to Tony, who came away as fresh as he had started, and a great deal happier, and more confident.

“Did us proud, Fred,” began the garrulous man.

“Yes, but that ’un ain’t nothing. You wait till he meets young Thomson. I’ve seen ’im box ’ere three years, and never bin beat yet. Three bloomin’ years. Yus.”

This might have depressed anybody else, but as Tony already knew all there was to be known about Allen’s skill with the gloves, it had no effect upon him.

A sanguinary heavy-weight encounter was followed by the first bout of the feathers and the second of the light-weights, and then it was Allen’s turn to fight the Harrow representative.

It was not a very exciting bout. Allen took things very easily. He knew his training was by no means all it should have been, and it was not his game to take it out of himself with any firework business in the trial heats. He would reserve that for the final. So he sparred three gentle rounds with the Harrow sportsman, just doing sufficient to keep the lead and obtain the verdict after the last round. He finished without having turned a hair. He had only received one really hard blow, and that had done no damage. After this came a long series of fights. The heavy-weights shed their blood in gallons for name and fame. The feather-weights gave excellent exhibitions of science, and the light-weight pairs were fought off until there remained only the final to be decided, Robinson, of St. Paul’s, against a Charterhouse boxer.

In the middle-weights there were three competitors still in the running, Allen, Tony, and a Felsted man. They drew lots, and the bye fell to Tony, who put up an uninteresting three rounds with one of the soldiers, neither fatiguing himself very much. Henderson, of Felsted, proved a much tougher nut to crack than Allen’s first opponent. He was a rushing boxer, and in the first round had, if anything, the best of it. In the last two, however, Allen gradually forged ahead, gaining many points by his perfect style alone. He was declared the winner, but he felt much more tired than he had done after his first fight.

By the time he was required again, however, he had had plenty of breathing space. The final of the light-weights had been decided, and Robinson, of St. Paul’s, after the custom of Paulines, had set the crown upon his afternoon’s work by fighting the Carthusian to a standstill in the first round. There only remained now the finals of the heavies and middles.

It was decided to take the latter first.

Tony had his former seconds, and Dawkins had come to his corner to see him through the ordeal.

“The ’ole thing ’ere,” he kept repeating, “is to keep goin’ ’ard all the time and wear ’im out. He’s too quick for you to try any sparrin’ with.”

“Hope I shall be able to get through his guard,” said Tony.

“Well, the ’ole thing there is to feint with your left and ’it with your right.” This was excellent in theory, no doubt, but Tony felt that when he came to put it into practice Allen might have other schemes on hand and bring them off first.

“Are you ready? Seconds out of the ring. . . . Time!”

“Go in, sir, ’ard,” whispered the red-haired man as Tony rose from his place.

Allen came up looking pleased with matters in general. He gave Tony a cousinly grin as they shook hands. Tony did not respond. He was feeling serious, and wondering if he could bring off his knock-out before the three rounds were over. He had his doubts.

The fight opened slowly. Both were cautious, for each knew the other’s powers. Suddenly, just as Tony was thinking of leading, Allen came in like a flash. A straight left between the eyes, a right on the side of the head, and a second left on the exact tip of the nose, and he was out again, leaving Tony with a helpless feeling of impotence and disgust.

Then followed more sparring. Tony could never get in exactly the right position for a rush. Allen circled round him with an occasional feint. Then he hit out with the left. Tony ducked. Again he hit, and again Tony ducked, but this time the left stopped halfway, and his right caught Tony on the cheek just as he swayed to one side. It staggered him, and before he could recover himself, in darted Allen again with another trio of blows, ducked a belated left counter, got in two stinging hits on the ribs, and finished with a left drive which took Tony clean off his feet and deposited him on the floor beside the ropes.

“Silence, please,” said the referee, as a burst of applause greeted this feat.

Tony was up again in a moment. He began to feel savage. He had expected something like this, but that gave him no consolation. He made up his mind that he really would rush this time, but just as he was coming in, Allen came in instead. It seemed to Tony for the next half-minute that his cousin’s fists were never out of his face. He looked on the world through a brown haze of boxing-glove. Occasionally his hand met something solid which he took to be Allen, but this was seldom, and, whenever it happened, it only seemed to bring him back again like a boomerang. Just at the most exciting point, “Time” was called.

The pessimist shook his head gloomily as he sponged Tony’s face.

“You must lead if you want to ’it ’im,” said the garrulous man. “You’re too slow. Go in at ’im, sir, wiv both ’ands, an’ you’ll be all right. Won’t ’e, Fred?”

“I said ’ow it ’ud be,” was the only reply Fred would vouchsafe.

Tony was half afraid the referee would give the fight against him without another round, but to his joy “Time” was duly called. He came up to the scratch as game as ever, though his head was singing. He meant to go in for all he was worth this round.

And go in he did. Allen had managed, in performing a complicated manoeuvre, to place himself in a corner, and Tony rushed. He was sent out again with a flush hit on the face. He rushed again, and again met Allen’s left. Then he got past, and in the confined space had it all his own way. Science did not tell here. Strength was the thing that scored, hard half-arm smashes, left and right, at face and body, and the guard could look after itself.

Allen upper-cut him twice, but after that he was nowhere. Tony went in with both hands. There was a prolonged rally, and it was not until “Time” had been called that Allen was able to extricate himself. Tony’s blows had been mostly body blows, and had played havoc with Allen’s wind.

“That’s right, sir,” was the comment of the red-headed second. “Keep ’em both goin’ hard, and you’ll win yet. You ’ad ’im proper then. ’Adn’t ’e, Fred?”

And even the pessimist was obliged to admit that Tony could fight, even if he was not quick with his guard.

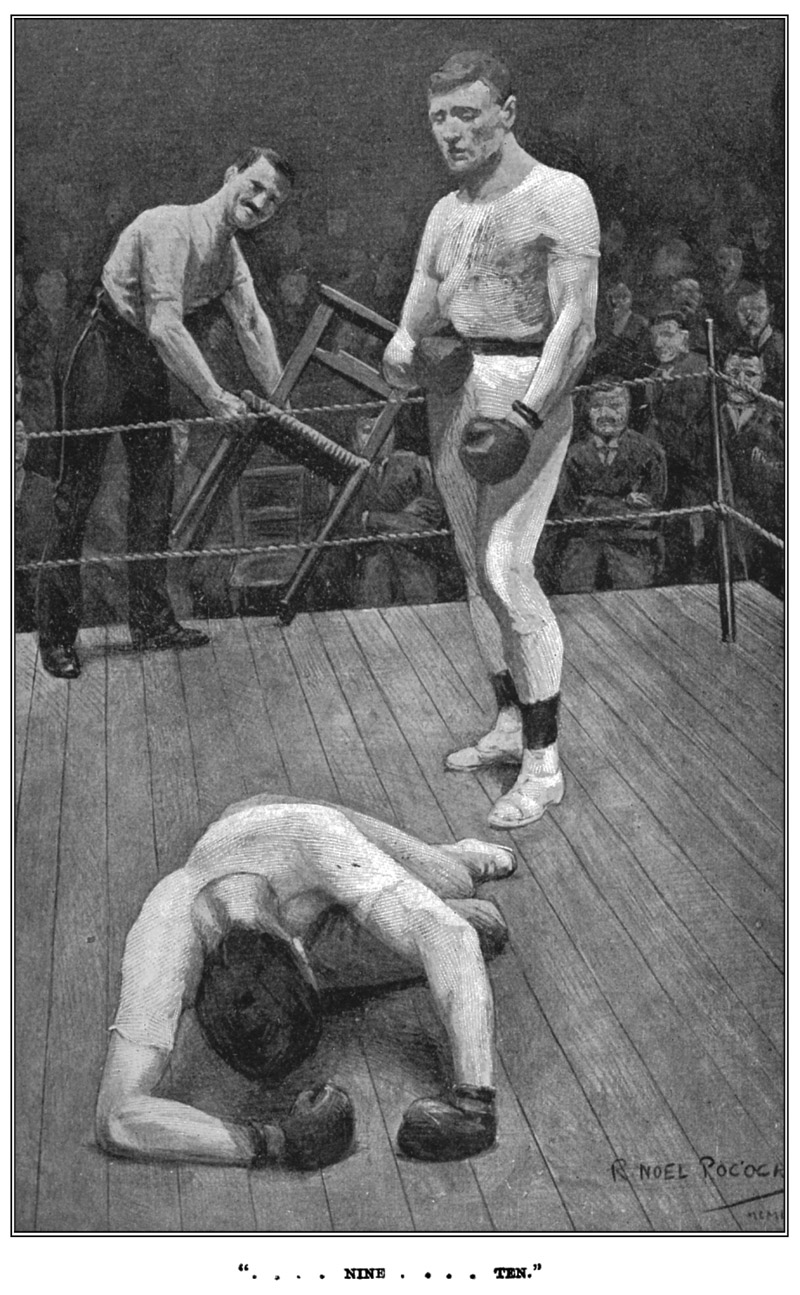

Allen took the ring slowly. His want of training had begun to tell on him, and some of Tony’s blows had landed in very tender spots. He knew that he could win if his wind held out, but he had misgivings. The gloves seemed to weigh down his hands. Tony opened the ball with a tremendous rush. Allen stopped him neatly. There was an interval while the two sparred for an opening. Then Allen feinted and dashed in. Tony did not hit him once. It was the first round over again. Left right, left right, and, finally, as had happened before, a tremendously hot shot which sent him under the ropes. He got up, and again Allen darted in. Tony met him with a straight left. A rapid exchange of blows, and the end came. Allen lashed out with his left. Tony ducked sharply, and brought his right across with every ounce of his weight behind it, fairly on to the point of the jaw. The right cross-counter is distinctly one of those things which it is more blessed to give than to receive. Allen collapsed.

“. . . . nine. . . . ten.”

The time-keeper closed his watch.

“Graham wins,” said the referee, “look after that man there.”

Chapter II.

It was always the custom for such Austinians as went up to represent the School at the annual competition to stop the night in the town. It was not, therefore, till just before breakfast on the following day that Tony arrived back at his House. The boarding-houses at St. Austin’s formed a fringe to the School grounds. The two largest were the School House and Merevale’s. Tony was at Merevale’s. He was walking up from the station with Welch, another member of Merevale’s, who had been up to Aldershot as a fencer, when, at the entrance to the School grounds, he fell in with Robinson, his fag. Robinson was supposed by many (including himself) to be a very warm man for the Junior Quarter, which was a handicap race, especially as an injudicious Sports Committee had given him ten yards’ start on Simpson, whom he would have backed himself to beat, even if the positions had been reversed. Being a wise youth, however, and knowing that the best of runners may fail through under-training, he had for the last week or so been going in for a steady course of over-training, getting up in the small hours and going for before-breakfast spins round the track on a glass of milk and a piece of bread. Master R. Robinson was nothing if not thorough in matters of this kind.

But to-day things of greater moment than the Sports occupied his mind. He had news. He had great news. He was bursting with news, and he hailed the approach of Tony and Welch with pleasure. With any other leading light of the School he might have felt less at ease, but with Tony it was different. When you have underdone a fellow’s eggs and overdone his toast and eaten the remainder for a term or two, you begin to feel that mere social distinctions and differences of age no longer form a barrier.

Besides, he had news which was absolutely fresh, news to which no one could say pityingly: “What! Have you only just heard that!”

“Hullo, Graham,” he said. “Have you come back? Jolly good you’re getting the Middles. (A telegram had, of course, preceded Tony.) I say, Graham, do you know what’s happened? There’ll be an awful row about it. Someone’s been and broken into the Pav.”

“Rot! How do you know?”

“There’s a pane taken clean out. I booked it in a second as I was going past to the track.”

“Which room?”

“First Fifteen. The window facing away from the Houses.”

“That’s rum,” said Welch. “Wonder what a burglar wanted in the first room. Isn’t even a hair-brush there generally.”

Robinson’s eyes dilated with honest pride. This was good. This was better than he had looked for. Not only were they unaware of the burglary, but they had not even an idea as to the recent event which had made the first-room so fit a hunting-ground for the burgling industry. There are few pleasures keener than the pleasure of telling somebody something he didn’t know before.

“Great Scott,” he remarked, “haven’t you heard? No, of course, you went up to Aldershot before they did it. By Jove.”

“Did what?”

“Why, they shunted all the Sports prizes from the board-room to the Pav. and shot ’em into the first-room. I don’t suppose there’s one left now. By Jove, won’t there be a row about it. I should like to see the Old Man’s face when he hears about it. Good mind to go and tell him now, only he’d have a fit. Jolly exciting, though, isn’t it?”

“Well,” said Tony, “of all the absolutely idiotic things to do! Fancy putting—there must have been at least fifty pounds’ worth of silver and things. Fancy going and leaving all that overnight in the Pav!”

“Rotten!” agreed Welch. “Wonder who’s idea it was.”

“Look here, Robinson,” said Tony, “you’d better buck up and change, or you’ll be late for brekker. Come on, Welch, we’ll go and inspect the scene of battle.”

Robinson trotted off, and Welch and Tony made their way to the Pavilion. There, sure enough, was the window, or rather the absence of window. A pane had been neatly removed, evidently in the orthodox way by means of a diamond.

“May as well climb up and see if there’s anything to be seen,” said Welch.

“All right,” said Tony, “give us a leg up. Right-ho. By Jove, I’m stiff.”

“See anything?”

“No. There’s a cloth sort of thing covering what I suppose are the prizes. I see how the chap, whoever he was, got in. You’ve only got to break the window, draw a couple of bolts, and there you are. Shall I go in and investigate?”

“Better not. It’s rather the thing, I fancy, in these sorts of cases, to leave everything just as it is.”

“Rum business,” said Tony, as he rejoined Welch on terra firma. “Wonder if they’ll catch the chap. We’d better be getting back to the House now. It struck the quarter years ago.”

When Tony, some twenty minutes later, shook off the admiring crowd who wanted a full description of yesterday’s proceedings, and reached his study, he found there James Thomson, brother to Allen Thomson, as the play-bills say. Jim was looking worried. Tony had noticed it during breakfast, and had wondered at the cause. He was soon enlightened.

“Hullo, Jim,” said he. “What’s up with you this morning? Feeling chippy?”

“No. No, I’m all right. I’m in a beastly hole though. I wanted to talk to you about it.”

“Weigh in, then. We’ve got plenty of time before school.”

“It’s about this Aldershot business. How on earth did you manage to lick Allen like that? I thought he was a cert.”

“Yes, so did I. The ’ole thing there, as Dawkins ’ud say, was, I knocked him out. It’s the sort of thing that’s always happening. I wasn’t in it at all except during the second round, when I gave him beans rather in one of the corners. My aunt, it was warm while it lasted. First round, I didn’t hit him once. He was better than I thought he’d be, and I knew from experience he was pretty good.”

“Yes, you look a bit bashed.”

“Yes. Feel it too. But what’s the row with you?”

“Just this. I had a couple of quid on Allen, and the rotter goes and gets licked.”

“Good Lord. Whom did you bet with?”

“With Allen himself.”

“Mean to say Allen was crock enough to bet against himself? He must have known he was miles better than anyone else in. He’s got three medals there already.”

“No, you see his bet with me was only a hedge. He’d got five to four or something in quids on with a chap in his House at Rugby on himself. He wanted a hedge because he wasn’t sure about his ankle being all right. You know he hurt it. So I gave him four to one in half-sovereigns. I thought he was a cert, with apologies to you.”

“Don’t mention it. So he was a cert. It was only the merest fluke I managed to out him when I did. If he’d hung on to the end, he’d have won easy. He’d been scoring points all through.”

“I know. So The Sportsman says. Just like my luck.”

“I can’t see what you want to bet at all for. You’re bound to come a mucker sooner or later. Can’t you raise the two quid?”

“I’m broke except for half a crown.”

“I’d lend it to you like a shot if I had it, of course. But you don’t find me with two quid to my name at the end of term. Won’t Allen wait?”

“He would if it was only him. But this other chap wants his oof badly for something, and he’s leaving and going abroad or something at the end of term. Anyhow, I know he’s keen on getting it. Allen told me.”

Tony pondered for a moment. “Look here,” he said at last, “can’t you ask your pater? He usually heaves his money about pretty readily, doesn’t he?”

“Well, you see, he wouldn’t send me two quid off the reel without wanting to know all about it, and why I couldn’t get on to the holidays with five bob, and I’d either have to make up a lot of lies, which I’m not going to do——”

“Of course not.”

“Or else I must tell him I’ve been betting.”

“Well, he bets himself, doesn’t he?”

“That’s just where the whole business slips up,” replied Jim, prodding the table with a pen in a misanthropic manner. “Betting’s the one thing he’s absolutely down on. He got done rather badly once a few years ago. Believe he betted on Orme that year he got poisoned. Anyhow he’s always sworn to lynch us if we made fools of ourselves that way. So if I asked him, I’d not only get beans myself, besides not getting any money out of him, but Allen would get scalped too, which he wouldn’t see at all.”

“Yes, it’s no good doing that. Haven’t you any other source of revenue?”

“Yes, there’s just one chance. If that doesn’t come off, I’m done. My pater said he’d give me a quid for every race I won at the Sports. I got the half yesterday all right when you were up at Aldershot.”

“Good man. I didn’t hear about that. What time? Anything good?”

“Nothing special. 2—7 and three-fifths.”

“That’s awfully good. You ought to pull off the mile, too, I should think.”

“Yes, with luck. Drake’s the man I’m afraid of. He’s done it in 4—48 twice during training. He was second in the half yesterday by about three yards, but you can’t tell anything from that. He sprinted too late.”

“What’s your best for the mile?”

“I have done 4—47, but only once. 4—48’s my average, so there’s nothing to choose between us on paper.”

“Well, you’ve got more to make you buck up than he has. There must be something in that.”

“Yes, by Jove. I’ll win if I expire on the tape. I shan’t spare myself with that quid on the horizon.”

“No. Hullo, there’s the bell. We must buck up. Going to Charteris’ gorge tonight?”

“Yes, but I shan’t eat anything. No risks for me.”

“Rusks are more in your line now. Come on.”

And, in the excitement of these more personal matters, Tony entirely forgot to impart the news of the Pavilion burglary to him.

(To be continued.)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums