The Strand Magazine, August 1923

NEVER in the course of a long and intimate acquaintance having been shown any evidence to the contrary, I had always looked on Stanley Featherstonehaugh Ukridge, my boyhood chum, as a man ruggedly indifferent to the appeal of the opposite sex. I had assumed that, like so many financial giants, he had no time for dalliance with women—other and deeper matters, I supposed, keeping that great brain permanently occupied. It was a surprise, therefore, when, passing down Shaftesbury Avenue one Wednesday afternoon in June at the hour when matinée audiences were leaving the theatres, I came upon him assisting a girl in a white dress to mount an omnibus.

As far as this simple ceremony could be rendered impressive, Ukridge made it so. His manner was a blend of courtliness and devotion; and if his mackintosh had been a shade less yellow and his hat a trifle less disreputable, he would have looked just like Sir Walter Raleigh.

The bus moved on, Ukridge waved, and I proceeded to make inquiries. I felt that I was an interested party. There had been a distinctly “object-matrimony” look about the back of his neck, it seemed to me; and the prospect of having to support a Mrs. Ukridge and keep a flock of little Ukridges in socks and shirts perturbed me.

“Who was that?” I asked.

“Oh, hullo, laddie!” said Ukridge, turning. “Where did you spring from? If you had come a moment earlier, I’d have introduced you to Dora.” The bus was lumbering out of sight into Piccadilly Circus, and the white figure on top turned and gave a final wave. “That was Dora Mason,” said Ukridge, having flapped a large hand in reply. “She’s my aunt’s secretary-companion. I used to see a bit of her from time to time when I was living at Wimbledon. Old Tuppy gave me a couple of seats for that show at the Apollo, so I thought it would be a kindly act to ask her along. I’m sorry for that girl. Sorry for her, old horse.”

“What’s the matter with her?”

“Hers is a grey life. She has few pleasures. It’s an act of charity to give her a little treat now and then. Think of it! Nothing to do all day but brush the Pekingese and type out my aunt’s rotten novels.”

“Does your aunt write novels?”

“The world’s worst, laddie, the world’s worst. She’s been steeped to the gills in literature ever since I can remember. They’ve just made her president of the Pen and Ink Club. As a matter of fact, it was her novels that did me in when I lived with her. She used to send me to bed with the beastly things and ask me questions about them at breakfast. Absolutely without exaggeration, laddie, at breakfast. It was a dog’s life and I’m glad it’s over. Flesh and blood couldn’t stand the strain. Well, knowing my aunt, I don’t mind telling you that my heart bleeds for poor little Dora. I know what a foul time she has, and I feel a better, finer man for having given her this passing gleam of sunshine. I wish I could have done more for her.”

“Well, you might have stood her tea after the theatre.”

“Not within the sphere of practical politics, laddie. Unless you can sneak out without paying, which is dashed difficult to do with these cashiers watching the door like weasels, tea even at an A.B.C. shop punches the pocket-book pretty hard, and at the moment I’m down to the scrapings. But I’ll tell you what, I don’t mind joining you in a cup, if you were thinking of it.”

“I wasn’t.”

“Come, come! A little more of the good old spirit of hospitality, old horse.”

“Why do you wear that beastly mackintosh in midsummer?”

“Don’t evade the point, laddie. I can see at a glance that you need tea. You’re looking pale and fagged.”

“Doctors say that tea is bad for the nerves.”

“Yes, possibly there’s something in that. Then I’ll tell you what,” said Ukridge, never too proud to yield a point, “we’ll make it a whisky-and-soda instead. Come along over to the Criterion.”

IT was a few days after this that the Derby was run, and a horse of the name of Gunga Din finished third. This did not interest the great bulk of the intelligentsia to any marked extent, the animal having started at a hundred to three, but it meant much to me, for I had drawn his name in the sweepstake at my club. After a monotonous series of blanks stretching back to the first year of my membership, this seemed to me the outstanding event of the century, and I celebrated my triumph by an informal dinner to a few friends. It was some small consolation to me later to remember that I had wanted to include Ukridge in the party, but failed to get hold of him. Dark hours were to follow, but at least Ukridge did not go through them bursting with my meat.

There is no form of spiritual exaltation so poignant as that which comes from winning even a third prize in a sweepstake. So tremendous was the moral uplift that, when eleven o’clock arrived, it seemed silly to sit talking in a club and still sillier to go to bed. I suggested spaciously that we should all go off and dress and resume the revels at my expense half an hour later at Mario’s, where, it being an extension night, there would be music and dancing till three. We scattered in cabs to our various homes.

How seldom in this life do we receive any premonition of impending disaster. I hummed a gay air as I entered the house in Ebury Street where I lodged, and not even the usually quelling sight of Bowles, my landlord, in the hall as I came in could quench my bonhomie. Generally a meeting with Bowles had the effect on me which the interior of a cathedral has on the devout, but to-night I was superior to this weakness.

“Ah, Bowles,” I cried, chummily, only just stopping myself from adding “Honest fellow!” “Hullo, Bowles! I say, Bowles, I drew Gunga Din in the club sweep.”

“Indeed, sir?”

“Yes. He came in third, you know.”

“So I see by the evening paper, sir. I congratulate you.”

“Thank you, Bowles, thank you.”

“Mr. Ukridge called earlier in the evening, sir,” said Bowles.

“Did he? Sorry I was out. I was trying to get hold of him. Did he want anything in particular?”

“Your dress-clothes, sir.”

“My dress-clothes, eh?” I laughed genially. “Extraordinary fellow! You never know——” A ghastly thought smote me like a blow. A cold wind seemed to blow through the hall. “He didn’t get them, did he?” I quavered.

“Why, yes, sir.”

“Got my dress-clothes?” I muttered, thickly, clutching for support at the hat-stand.

“He said it would be all right, sir,” said Bowles, with that sickening tolerance which he always exhibited for all that Ukridge said or did. One of the leading mysteries of my life was my landlord’s amazing attitude towards this hell-hound. He fawned on the man. A splendid fellow like myself had to go about in a state of hushed reverence towards Bowles, while a human blot like Ukridge could bellow at him over the banisters without the slightest rebuke. It was one of those things which make one laugh cynically when people talk about the equality of man.

“He got my dress-clothes?” I mumbled.

“Mr. Ukridge said that he knew you would be glad to let him have them, as you would not be requiring them to-night.”

“But I do require them, damn it!” I shouted, lost to all proper feeling. Never before had I let fall an oath in Bowles’s presence. “I’m giving half-a-dozen men supper at Mario’s in a quarter of an hour.”

Bowles clicked his tongue sympathetically.

“What am I going to do?”

“Perhaps if you would allow me to lend you mine, sir?”

“Yours?”

“I have a very nice suit. It was given to me by his lordship the late Earl of Oxted, in whose employment I was for many years. I fancy it would do very well on you, sir. His lordship was about your height, though perhaps a little slenderer. Shall I fetch it, sir? I have it in a trunk downstairs.”

The obligations of hospitality are sacred. In fifteen minutes’ time six jovial men would be assembling at Mario’s and what would they do, lacking a host? I nodded feebly.

“It’s very kind of you,” I managed to say.

“Not at all, sir. It is a pleasure.”

If he was speaking the truth, I was glad of it. It is nice to think that the affair brought pleasure to someone.

That the late Earl of Oxted had indeed been a somewhat slenderer man than myself became manifest to me from the first pulling on of the trousers. Hitherto I had always admired the slim, small-boned type of aristocrat, but it was not long before I was wishing that Bowles had been in the employment of someone who had gone in a little more heartily for starchy foods. And I regretted, moreover, that the fashion of wearing a velvet collar on an evening coat, if it had to come in at all, had not lasted a few years longer. Dim as the light in my bedroom was, it was strong enough to make me wince as I looked in the mirror.

And I was aware of a curious odour.

“Isn’t this room a trifle stuffy, Bowles?”

“No, sir. I think not.”

“Don’t you notice an odd smell?”

“No, sir. But I have a somewhat heavy cold. If you are ready, sir, I will call a cab.”

MOTH-BALLS! That was the scent I had detected. It swept upon me like a wave in the cab. It accompanied me like a fog all the way to Mario’s, and burst out in its full fragrance when I entered the place and removed my overcoat. The cloak-room waiter sniffed in a startled way as he gave me my check, one or two people standing near hastened to remove themselves from my immediate neighbourhood, and my friends, when I joined them, expressed themselves with friend-like candour. With a solid unanimity they told me frankly that it was only the fact that I was paying for the supper that enabled them to tolerate my presence.

The leper-like feeling induced by this uncharitable attitude caused me after the conclusion of the meal to withdraw to the balcony to smoke in solitude. My guests were dancing merrily, but such pleasures were not for me. Besides, my velvet collar had already excited ribald comment, and I am a sensitive man. Crouched in a lonely corner of the balcony, surrounded by the outcasts who were not allowed on the lower floor because they were not dressed, I chewed a cigar and watched the revels with a jaundiced eye. The space reserved for dancing was crowded, and couples either revolved warily or ruthlessly bumped a passage for themselves, using their partners as battering-rams. Prominent among the ruthless bumpers was a big man who was giving a realistic imitation of a steam-plough. He danced strongly and energetically, and when he struck the line, something had to give.

From the very first, something about this man had seemed familiar; but owing to his peculiar crouching manner of dancing, which he seemed to have modelled on the ring-style of Mr. James J. Jeffries, it was not immediately that I was able to see his face. But presently, as the music stopped and he straightened himself to clap his hands for an encore, his foul features were revealed to me.

It was Ukridge. Ukridge, confound him, with my dress-clothes fitting him so perfectly and with such unwrinkled smoothness that he might have stepped straight out of one of Ouida’s novels. Until that moment I had never fully realized the meaning of the expression “faultless evening dress.” With a passionate cry I leaped from my seat, and accompanied by a rich smell of camphor bounded for the stairs. Like Hamlet on a less impressive occasion, I wanted to slay this man when he was full of bread, with all his crimes broad-blown, as flush as May, at drinking, swearing, or about some act that had no relish of salvation in it.

“But, laddie,” said Ukridge, backed into a corner of the lobby apart from the throng, “be reasonable.”

I cleansed my bosom of a good deal of that perilous stuff that weighs upon the heart.

“How could I guess that you would want the things? Look at it from my position, old horse. I knew you, laddie, a good true friend who would be delighted to lend a pal his dress-clothes any time when he didn’t need them himself, and as you weren’t there when I called I couldn’t ask you, so I naturally simply borrowed them. It was all just one of those little misunderstandings which can’t be helped. And, as it luckily turns out, you had a spare suit, so everything was all right, after all.”

“You don’t think this poisonous fancy dress is mine, do you?”

“Isn’t it?” said Ukridge, astonished.

“It belongs to Bowles. He lent it to me.”

“And most extraordinarily well you look in it, laddie,” said Ukridge. “Upon my Sam, you look like a duke or something.”

“And smell like a second-hand clothes-store.”

“Nonsense, my dear old son, nonsense. A mere faint suggestion of some rather pleasant antiseptic. Nothing more. I like it. It’s invigorating. Honestly, old man, it’s really remarkable what an air that suit gives you. Distinguished. That’s the word I was searching for. You look distinguished. All the girls are saying so. When you came in just now to speak to me, I heard one of them whisper ‘Who is it?’ That shows you.”

“More likely ‘What is it?’ ”

“Ha, ha!” bellowed Ukridge, seeking to cajole me with sycophantic mirth. “Dashed good! Deuced good! Not ‘Who is it?’ but ‘What is it?’ It beats me how you think of these things. Golly, if I had a brain like yours—— But now, old son, if you don’t mind, I really must be getting back to poor little Dora. She’ll be wondering what has become of me.”

The significance of these words had the effect of making me forget my just wrath for a moment.

“Are you here with that girl you took to the theatre the other afternoon?”

“Yes. I happened to win a trifle on the Derby, so I thought it would be the decent thing to ask her out for an evening’s pleasure. Hers is a grey life.”

“It must be, seeing you so much.”

“A little personal, old horse,” said Ukridge reprovingly. “A trifle bitter. But I know you don’t mean it. Yours is a heart of gold really. If I’ve said that once, I’ve said it a hundred times. Always saying it. Rugged exterior but heart of gold. My very words. Well, good-bye for the present, laddie. I’ll look in to-morrow and return these things. I’m sorry there was any misunderstanding about them, but it makes up for everything, doesn’t it, to feel that you’ve helped brighten life for a poor little downtrodden thing who has few pleasures.”

“Just one last word,” I said. “One final remark.”

“Yes?”

“I’m sitting in that corner of the balcony over there,” I said. “I mention the fact so that you can look out for yourself. If you come dancing underneath there, I shall drop a plate on you. And if it kills you, so much the better. I’m a poor downtrodden little thing and I have few pleasures.”

OWING to a mawkish respect for the conventions, for which I reproach myself, I did not actually perform this service to humanity. With the exception of throwing a roll at him—which missed him but most fortunately hit the member of my supper-party who had sniffed with the most noticeable offensiveness at my camphorated costume—I took no punitive measures against Ukridge that night. But his demeanour, when he called at my rooms next day, could not have been more crushed if I had dropped a pound of lead on him. He strode into my sitting-room with the sombre tread of the man who in a conflict with Fate has received the loser’s end. I had been passing in my mind a number of good snappy things to say to him, but his appearance touched me to such an extent that I held them in. To abuse this man would have been like dancing on a tomb.

“For Heaven’s sake what’s the matter?” I asked. “You look like a toad under the harrow.”

He sat down creakingly, and lit one of my cigars.

“Poor little Dora!”

“What about her?”

“She’s got the push!”

“The push? From your aunt’s, do you mean?”

“Yes.”

“What for?”

Ukridge sighed heavily.

“Most unfortunate business, old horse, and largely my fault. I thought the whole thing was perfectly safe. You see, my aunt goes to bed at half-past ten every night, so it seemed to me that if Dora slipped out at eleven and left a window open behind her she could sneak back all right when we got home from Mario’s. But what happened? Some dashed officious ass,” said Ukridge, with honest wrath, “went and locked the damned window. I don’t know who it was. I suspect the butler. He has a nasty habit of going round the place late at night and shutting things. Upon my Sam, it’s a little hard! If only people would leave things alone and not go snooping about——”

“What happened?”

“Why, it was the scullery window which we’d left open, and when we got back at four o’clock this morning the infernal thing was shut as tight as an egg. Things looked pretty rocky, but Dora remembered that her bedroom window was always open, so we bucked up again for a bit. Her room’s on the second floor, but I knew where there was a ladder, so I went and got it, and she was just hopping up as merry as dammit when somebody flashed a great beastly lantern on us, and there was a policeman, wanting to know what the game was. The whole trouble with the police force of London, laddie, the thing that makes them a hissing and a byword, is that they’re snoopers to a man. Zeal, I suppose they call it. Why they can’t attend to their own affairs is more than I can understand. Dozens of murders going on all the time, probably, all over Wimbledon, and all this bloke would do was stand and wiggle his infernal lantern and ask what the game was. Wouldn’t be satisfied with a plain statement that it was all right. Insisted on rousing the house to have us identified.”

Ukridge paused, a reminiscent look of pain on his expressive face.

“And then?” I said.

“We were,” said Ukridge, briefly.

“What?”

“Identified. By my aunt. In a dressing-gown and a revolver. And the long and the short of it is, old man, that poor little Dora has got the sack.”

I could not find it in my heart to blame his aunt for what he evidently considered a high-handed and tyrannical outrage. If I were a maiden lady of regular views, I should relieve myself of the services of any secretary-companion who returned to roost only a few short hours in advance of the milk. But, as Ukridge plainly desired sympathy rather than an austere pronouncement on the relations of employer and employed, I threw him a couple of tuts, which seemed to soothe him a little. He turned to the practical side of the matter.

“What’s to be done?”

“I don’t see what you can do.”

“But I must do something. I’ve lost the poor little thing her job, and I must try to get it back. It’s a rotten sort of job, but it’s her bread and butter. Do you think George Tupper would biff round and have a chat with my aunt, if I asked him?”

“I suppose he would. He’s the best-hearted man in the world. But I doubt if he’ll be able to do much.”

“Nonsense, laddie,” said Ukridge, his unconquerable optimism rising bravely from the depths. “I have the utmost confidence in old Tuppy. A man in a million. And he’s such a dashed respectable sort of bloke that he might have her jumping through hoops and shamming dead before she knew what was happening to her. You never know. Yes, I’ll try old Tuppy. I’ll go and see him now.”

“I should.”

“Just lend me a trifle for a cab, old son, and I shall be able to get to the Foreign Office before one o’clock. I mean to say, even if nothing comes of it, I shall be able to get a lunch out of him. And I need refreshment, laddie, need it sorely. The whole business has shaken me very much.”

IT was three days after this that, stirred by a pleasant scent of bacon and coffee, I hurried my dressing and, proceeding to my sitting-room, found that Ukridge had dropped in to take breakfast with me, as was often his companionable practice. He seemed thoroughly cheerful again, and was plying knife and fork briskly like the good trencherman he was.

“Morning, old horse,” he said, agreeably.

“Good morning.”

“Devilish good bacon, this. As good as I’ve ever bitten. Bowles is cooking you some more.”

“That’s nice. I’ll have a cup of coffee, if you don’t mind me making myself at home while I’m waiting.” I started to open the letters by my plate, and became aware that my guest was eyeing me with a stare of intense penetration through his pince-nez, which were all crooked as usual. “What’s the matter?”

“Matter?”

“Why,” I said, “are you looking at me like a fish with lung-trouble?”

“Was I?” He took a sip of coffee with an overdone carelessness. “Matter of fact, old son, I was rather interested. I see you’ve had a letter from my aunt.”

“What?”

I had picked up the last envelope. It was addressed in a strong female hand, strange to me. I now tore it open. It was even as Ukridge had said. Dated the previous day and headed “Heath House, Wimbledon Common,” the letter ran as follows:—

Dear Sir,—I shall be happy to see you if you will call at this address the day after to-morrow (Friday) at four-thirty.—Yours faithfully, Julia Ukridge.

I could make nothing of this. My morning mail, whether pleasant or the reverse, whether bringing a bill from a tradesman or a cheque from an editor, had had till now the uniform quality of being plain, straightforward, and easy to understand; but this communication baffled me. How Ukridge’s aunt had become aware of my existence and why a call from me should ameliorate her lot were problems beyond my unravelling, and I brooded over it as an Egyptologist might over some newly-discovered hieroglyphic.

“What does she say?” inquired Ukridge.

“She wants me to call at half-past four to-morrow afternoon.”

“Splendid!” cried Ukridge. “I knew she would bite.”

“What on earth are you talking about?”

Ukridge reached across the table and patted me affectionately on the shoulder. The movement involved the upsetting of a full cup of coffee, but I suppose he meant well. He sank back again in his chair and adjusted his pince-nez in order to get a better view of me. I seemed to fill him with honest joy, and he suddenly burst into a spirited eulogy, rather like some minstrel of old delivering an extempore boost of his chieftain and employer.

“Laddie,” said Ukridge, “if there’s one thing about you that I’ve always admired it’s your readiness to help a pal. One of the most admirable qualities a bloke can possess, and nobody has it to a greater extent than you. You’re practically unique in that way. I’ve had men come up to me and ask me about you. ‘What sort of chap is he?’ they say. ‘One of the very best,’ I reply. ‘A fellow you can rely on. A man who would die rather than let you down. A bloke who would go through fire and water to do a pal a good turn. A bird with a heart of gold and a nature as true as steel.’ ”

“Yes, I’m a splendid fellow,” I agreed, slightly perplexed by this panegyric. “Get on.”

“I am getting on, old horse,” said Ukridge with faint reproach. “What I’m trying to say is that I knew you would be delighted to tackle this little job for me. It wasn’t necessary to ask you. I knew.”

A GRIM foreboding of an awful doom crept over me, as it had done so often before in my association with Ukridge.

“Will you kindly tell me what damned thing you’ve let me in for now?”

Ukridge deprecated my warmth with a wave of his fork. He spoke soothingly and with a winning persuasiveness. He practically cooed.

“It’s nothing, laddie. Practically nothing. Just a simple little act of kindness which you will thank me for putting in your way. It’s like this. As I ought to have foreseen from the first, that ass Tuppy proved a broken reed. In that matter of Dora, you know. Got no result whatever. He went to see my aunt the day before yesterday, and asked her to take Dora on again, and she gave him the miss-in-baulk. I’m not surprised. I never had any confidence in Tuppy. It was a mistake ever sending him. It’s no good trying frontal attack in a delicate business like this. What you need is strategy. You want to think what is the enemy’s weak side and then attack from that angle. Now, what is my aunt’s weak side, laddie? Her weak side, what is it? Now think. Reflect, old horse.”

“From the sound of her voice, the only time I ever got near her, I should say she hadn’t one.”

“That’s where you make your error, old son. Butter her up about her beastly novels, and a child could eat out of her hand. When Tuppy let me down I just lit a pipe and had a good think. And then suddenly I got it. I went to a pal of mine, a thorough sportsman—you don’t know him. I must introduce you some day—and he wrote my aunt a letter from you, asking if you could come and interview her for Woman’s Sphere. It’s a weekly paper, which I happen to know she takes in regularly. Now, listen, laddie. Don’t interrupt for a moment. I want you to get the devilish shrewdness of this. You go and interview her, and she’s all over you. Tickled to death. Of course, you’ll have to do a good deal of Young Disciple stuff, but you won’t mind that. After you’ve soft-soaped her till she’s purring like a dynamo, you get up to go. ‘Well,’ you say, ‘this has been the proudest occasion of my life, meeting one whose work I have so long admired.’ And she says, ‘The pleasure is mine, old horse.’ And you slop over each other a bit more. Then you say sort of casually, as if it had just occurred to you, ‘Oh, by the way, I believe my cousin—or sister—— No, better make it cousin—I believe my cousin, Miss Dora Mason, is your secretary, isn’t she?’ ‘She isn’t any such dam’ thing,’ replies my aunt. ‘I sacked her three days ago.’ That’s your cue, laddie. Your face falls, you register concern, you’re frightfully cut up. You start in to ask her to let Dora come back. And you’re such pals by this time that she can refuse you nothing. And there you are! My dear old son, you can take it from me that if you only keep your head and do the Young Disciple stuff properly the thing can’t fail. It’s an iron-clad scheme. There isn’t a flaw in it.”

“There is one.”

“I think you’re wrong. I’ve gone over the thing very carefully. What is it?”

“The flaw is that I’m not going anywhere near your infernal aunt. So you can trot back to your forger chum and tell him he’s wasted a good sheet of letter-paper.”

A pair of pince-nez tinkled into a plate. Two pained eyes blinked at me across the table. Stanley Featherstonehaugh Ukridge was wounded to the quick.

“You don’t mean to say you’re backing out?” he said, in a low, quivering voice.

“I never was in.”

“Laddie,” said Ukridge, weightily, resting an elbow on his last slice of bacon, “I want to ask you one question. Just one simple question. Have you ever let me down? Has there been one occasion in our long friendship when I have relied upon you and been deceived? Not one!”

“Everything’s got to have a beginning. I’m starting now.”

“But think of her. Dora! Poor little Dora. Think of poor little Dora.”

“If this business teaches her to keep away from you, it will be a blessing in the end.”

“But, laddie——”

I suppose there is some fatal weakness in my character, or else the brand of bacon which Bowles cooked possessed a peculiarly mellowing quality. All I know is that, after being adamant for a good ten minutes, I finished breakfast committed to a task from which my soul revolted. After all, as Ukridge said, it was rough on the girl. Chivalry is chivalry. We must strive to lend a helping hand as we go through this world of ours, and all that sort of thing. Four o’clock on the following afternoon found me entering a cab and giving the driver the address of Heath House, Wimbledon Common.

MY emotions on entering Heath House were such as I would have felt had I been keeping a tryst with a dentist who by some strange freak happened also to be a duke. From the moment when a butler of super-Bowles dignity opened the door and, after regarding me with ill-concealed dislike, started to conduct me down a long hall, I was in the grip of both fear and humility. Heath House is one of the stately homes of Wimbledon; how beautiful they stand, as the poet says: and after the humble drabness of Ebury Street it frankly overawed me. Its keynote was an extreme neatness which seemed to sneer at my squashy collar and reproach my baggy trouser-leg. The farther I penetrated over the polished floor, the more vividly was it brought home to me that I was one of the submerged tenth and could have done with a hair-cut. I had not been aware when I left home that my hair was unusually long, but now I seemed to be festooned by a matted and offensive growth. A patch on my left shoe which had had a rather comfortable look in Ebury Street stood out like a blot on the landscape. No, I was not at my ease; and when I reflected that in a few moments I was to meet Ukridge’s aunt, that legendary figure, face to face, a sort of wistful admiration filled me for the beauty of the nature of one who would go through all this to help a girl he had never even met. There was no doubt about it—the facts spoke for themselves—I was one of the finest fellows I had ever known. Nevertheless, there was no getting away from it, my trousers did bag at the knee.

“Mr. Corcoran,” announced the butler, opening the drawing-room door. He spoke with just that intonation of voice that seemed to disclaim all responsibility. If I had an appointment, he intimated, it was his duty, however repulsive, to show me in; but, that done, he disassociated himself entirely from the whole affair.

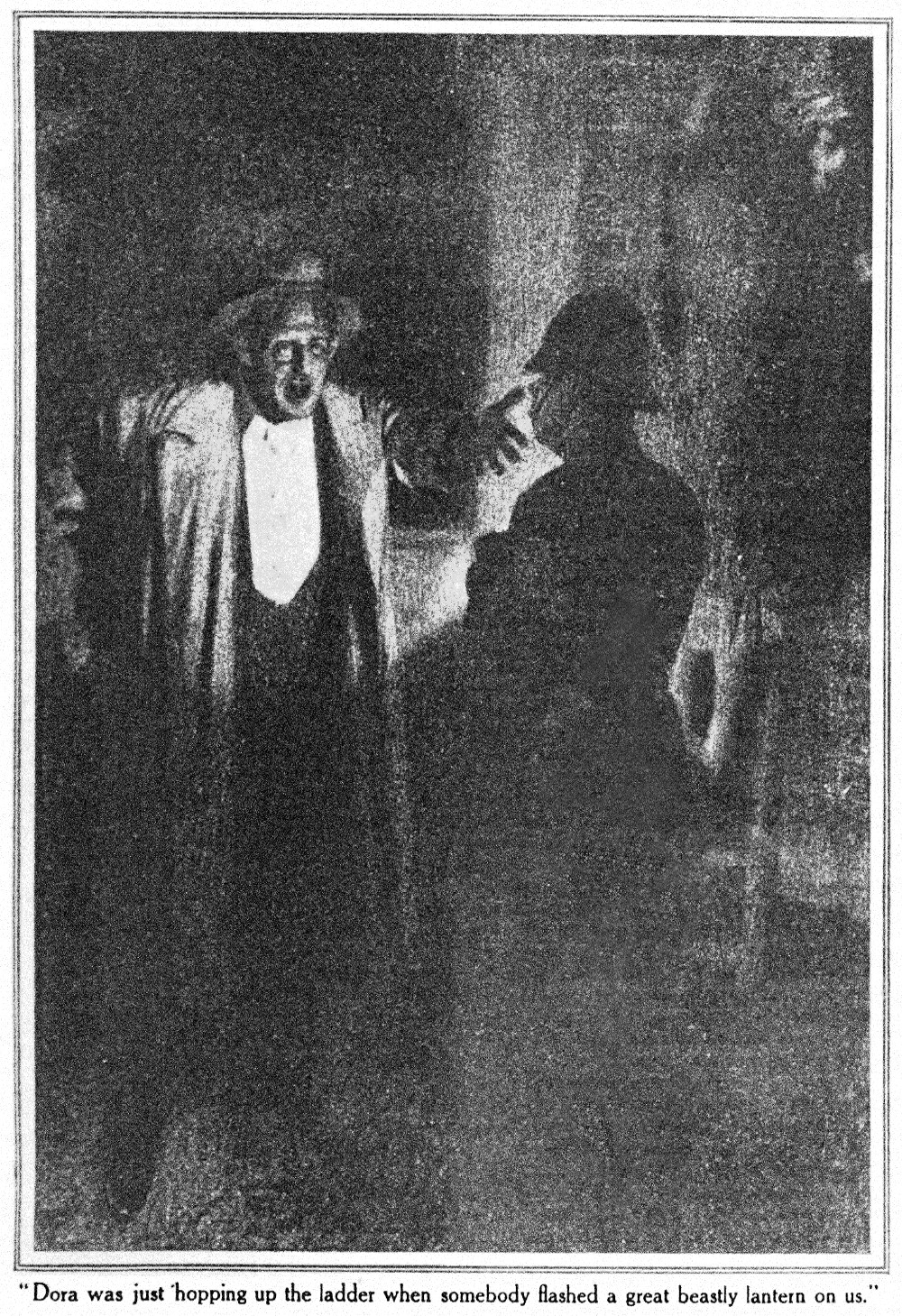

There were two women and six Pekingese dogs in the room. The Pekes I had met before, during their brief undergraduate days at Ukridge’s dog college, but they did not appear to recognize me. The occasion when they had lunched at my expense seemed to have passed from their minds. One by one they came up, sniffed, and then moved away as if my bouquet had disappointed them. They gave the impression that they saw eye to eye with the butler in his estimate of the young visitor. I was left to face the two women.

Of these—reading from right to left—one was a tall, angular, hawk-faced female with a stony eye. The other, to whom I gave but a passing glance at the moment, was small and, so it seemed to me, pleasant-looking. She had bright hair faintly powdered with grey and mild eyes of a china blue. She reminded me of the better class of cat. I took her to be some casual caller who had looked in for a cup of tea. It was the hawk on whom I riveted my attention. She was looking at me with a piercing and unpleasant stare, and I thought how exactly she resembled the picture I had formed of her in my mind from Ukridge’s conversation.

“Miss Ukridge?” I said, sliding on a rug towards her and feeling like some novice whose manager, against his personal wishes, has fixed him up with a match with the heavyweight champion.

“I am Miss Ukridge,” said the other woman. “Miss Watterson, Mr. Corcoran.”

It was a shock, but, the moment of surprise over, I began to feel something approaching mental comfort for the first time since I had entered this house of slippery rugs and supercilious butlers. Somehow I had got the impression from Ukridge that his aunt was a sort of stage aunt, all stiff satin and raised eyebrows. This half-portion with the mild blue eyes I felt that I could tackle. It passed my comprehension why Ukridge should ever have found her intimidating.

“I hope you will not mind if we have our little talk before Miss Watterson,” she said with a charming smile. “She has come to arrange the details of the Pen and Ink Club dance which we are giving shortly. She will keep quite quiet and not interrupt. You don’t mind?”

“Not at all, not at all,” I said in my attractive way. It is not exaggerating to say that at this moment I felt debonair. “Not at all, not at all. Oh, not at all.”

“Won’t you sit down?”

“Thank you, thank you.”

The hawk moved over to the window, leaving us to ourselves.

“Now we are quite cosy,” said Ukridge’s aunt.

“Yes, yes,” I agreed. Dash it, I liked this woman.

“Tell me, Mr. Corcoran,” said Ukridge’s aunt, “are you on the staff of Woman’s Sphere? It is one of my favourite papers. I read it every week.”

“The outside staff.”

“What do you mean by the outside staff?”

“Well, I don’t actually work in the office, but the editor gives me occasional jobs.”

“I see. Who is the editor now?”

I began to feel slightly less debonair. She was just making conversation, of course, to put me at my ease, but I wished she would stop asking me these questions. I searched desperately in my mind for a name—any name—but as usual on these occasions every name in the English language had passed from me.

“Of course. I remember now,” said Ukridge’s aunt, to my profound relief. “It’s Mr. Jevons, isn’t it? I met him one night at dinner.”

“Jevons,” I burbled. “That’s right. Jevons.”

“A tall man with a light moustache.”

“Well, fairly tall,” I said, judicially.

“And he sent you here to interview me?”

“Yes.”

“Well, which of my novels do you wish me to talk about?”

I relaxed with a delightful sense of relief. I felt on solid ground at last. And then it suddenly came to me that Ukridge in his woollen-headed way had omitted to mention the name of a single one of this woman’s books.

“Er—oh, all of them,” I said, hurriedly.

“I see. My general literary work.”

“Exactly,” I said. My feeling towards her now was one of positive affection.

She leaned back in her chair with her finger-tips together, a pretty look of meditation on her face.

“Do you think it would interest the readers of Woman’s Sphere to know which novel of mine is my own favourite?”

“I am sure it would.”

“Of course,” said Ukridge’s aunt, “it is not easy for an author to answer a question like that. You see, one has moods in which first one book and then another appeals to one.”

“Quite,” I replied. “Quite.”

“Which of my books do you like best, Mr. Corcoran?”

There swept over me the trapped feeling one gets in nightmares. From six baskets the six Pekingese stared at me unwinkingly.

“Er—oh, all of them,” I heard a croaking voice reply. My voice, presumably, though I did not recognize it.

“How delightful!” said Ukridge’s aunt. “Now, I really do call that delightful. One or two of the critics have said that my work was uneven. It is so nice to meet someone who doesn’t agree with them. Personally, I think my favourite is ‘The Heart of Adelaide.’ ”

I nodded my approval of this sound choice. The muscles which had humped themselves stiffly on my back began to crawl back into place again. I found it possible to breathe.

“Yes,” I said, frowning thoughtfully, “I suppose ‘The Heart of Adelaide’ is the best thing you have written. It has such human appeal,” I added, playing it safe.

“Have you read it, Mr. Corcoran?”

“Oh, yes.”

“And you really enjoyed it?”

“Tremendously.”

“You don’t think it is a fair criticism to say that it is a little broad in parts?”

“Most unfair.” I began to see my way. I do not know why, but I had been assuming that her novels must be the sort you find in seaside libraries. Evidently they belonged to the other class of female novels, the sort which libraries ban. “Of course,” I said, “it is written honestly, fearlessly, and shows life as it is. But broad? No, no!”

“That scene in the conservatory?”

“Best thing in the book,” I said, stoutly.

A pleased smile played about her mouth. Ukridge had been right. Praise her work, and a child could eat out of her hand. I found myself wishing that I had really read the thing, so that I could have gone into more detail and made her still happier.

“I’m so glad you like it,” she said. “Really, it is most encouraging.”

“Oh, no,” I murmured, modestly.

“Oh, but it is. Because I have only just started to write it, you see. I finished chapter one this morning.”

She was still smiling so engagingly that for a moment the full horror of these words did not penetrate my consciousness.

“ ‘The Heart of Adelaide’ is my next novel. The scene in the conservatory, which you like so much, comes towards the middle of it. I was not expecting to reach it till about the end of next month. How odd that you should know all about it!”

I had got it now all right, and it was like sitting down on the empty space where there should have been a chair. Somehow the fact that she was so pleasant about it all served to deepen my discomfiture. In the course of an active life I have frequently felt a fool, but never such a fool as I felt then. The fearful woman had been playing with me, leading me on, watching me entangle myself like a fly on fly-paper. And suddenly I perceived that I had erred in thinking of her eyes as mild. A hard gleam had come into them. They were like a couple of blue gimlets. She looked like a cat that had caught a mouse, and it was revealed to me in one sickening age-long instant why Ukridge went in fear of her. There was that about her which would have intimidated the Sheik.

“It seems so odd, too,” she tinkled on, “that you should have come to interview me for Woman’s Sphere. Because they published an interview with me only the week before last. I thought it so strange that I rang up my friend Miss Watterson, who is the editress, and asked her if there had not been some mistake. And she said she had never heard of you. Have you ever heard of Mr. Corcoran, Muriel?”

“Never,” said the hawk, fixing me with a revolted eye.

“How strange!” said Ukridge’s aunt. “But then the whole thing is so strange. Oh, must you go, Mr. Corcoran?”

My mind was in a slightly chaotic condition, but on that one point it was crystal-clear. Yes, I must go. Through the door if I could find it—failing that, through the window. And anybody who tried to stop me would do well to have a care.

“You will remember me to Mr. Jevons when you see him, won’t you?” said Ukridge’s aunt.

I was fumbling at the handle.

“And, Mr. Corcoran.” She was still smiling amiably, but there had come into her voice a note like that which it bad had on a certain memorable occasion when summoning Ukridge to his doom from the unseen interior of his Sheep’s Cray cottage. “Will you please tell my nephew Stanley that I should be glad if he would send no more of his friends to see me. Good afternoon.”

I suppose that at some point in the proceedings my hostess must have rung a bell, for out in the passage I found my old chum, the butler. With the uncanny telepathy of his species he appeared aware that I was leaving under what might be called a cloud, for his manner had taken on a warder-like grimness. His hand looked as if it was itching to grasp me by the shoulder, and when we reached the front door he eyed the pavement wistfully, as if thinking what a splendid spot it would be for me to hit with a thud.

“Nice day,” I said, with the feverish instinct to babble which comes to strong men in their agony.

He scorned to reply, and as I tottered down the sunlit street I was conscious of his gaze following me.

“A very vicious specimen,” I could fancy him saying. “And mainly due to my prudence and foresight that he hasn’t got away with the spoons.”

IT was a warm afternoon, but to such an extent had the recent happenings churned up my emotions that I walked the whole way back to Ebury Street with a rapidity which caused more languid pedestrians to regard me with a pitying contempt. Reaching my sitting-room in an advanced state of solubility and fatigue, I found Ukridge stretched upon the sofa.

“Hullo, laddie!” said Ukridge, reaching out a hand for the cooling drink that lay on the floor beside him. “I was wondering when you would show up. I wanted to tell you that it won’t be necessary for you to go and see my aunt after all. It appears that Dora has a hundred quid tucked away in a bank, and she’s been offered a partnership by a woman she knows who runs one of these typewriting places. I advised her to close with it. So she’s all right.”

He quaffed deeply of the bowl and breathed a contented sigh. There was a silence.

“When did you hear of this?” I asked at length.

“Yesterday afternoon,” said Ukridge. “I meant to pop round and tell you, but somehow it slipped my mind.”

(Next month: “The Return of Battling Billson.” )

Notes:

See the annotations to this story as it appeared in book form in the collection Ukridge (1924).

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums