Strand Magazine, February 1906

Y brother

Bob sometimes says that if he dies young or gets white hair at the age of

thirty it will be all my fault. He says that I was bad

at fifteen, worse at sixteen, while “present day,” as they put it in

the biographies of celebrities, I am simply awful. This is very ungrateful of

him, because I have always done my best to make him a credit to the family. He

is just beginning his second year at Oxford, so, naturally, he wants

repressing. Ever since I put my hair up—and that is nearly a year ago now—I

have seen that I was the only person to do this. Father doesn’t notice things.

Besides, Bob is always on his best behaviour with

father.

Y brother

Bob sometimes says that if he dies young or gets white hair at the age of

thirty it will be all my fault. He says that I was bad

at fifteen, worse at sixteen, while “present day,” as they put it in

the biographies of celebrities, I am simply awful. This is very ungrateful of

him, because I have always done my best to make him a credit to the family. He

is just beginning his second year at Oxford, so, naturally, he wants

repressing. Ever since I put my hair up—and that is nearly a year ago now—I

have seen that I was the only person to do this. Father doesn’t notice things.

Besides, Bob is always on his best behaviour with

father.

Just at present, however, there was a sort of truce. I was very grateful to Bob because, you see, if it had not been for him I should not have thought of getting Saunders to make Mr. Simpson let father hit his bowling about in the match with the Cave men, and then father wouldn’t have taken me to London for the winter, and if I had had to stay at Much Middlefold all the winter I should have pined away. So that I had a great deal to thank Bob for, and I was very kind to him till he went back to Oxford for the winter term; and I was still on the lookout for a chance of paying back one good turn with another.

We had taken a jolly house in Sloane Street from October, and I was having the most perfect time. I’m afraid father was hating it, though. He said to me at dinner one night, “One thousand five hundred and twenty-three vehicles passed the window of the club this morning, Joan.”

“How do you know?” I asked.

“I counted them.”

“Father, what a waste of time!”

“Why, what else is there to do in London?” he said.

I could have told him millions of things, but I suppose if you don’t like London it isn’t any fun looking at the sort of sights I like to see.

The morning after this, when father had gone off to his club—to count cabs again, I suppose—I got a letter from Bob.

“Dear Kid” (he wrote),—“Just a line. Hope you’re having a good time in London. I can’t come down for Aunt Edith’s ball on your birthday, as they won’t let me. I tried it on, but the Dean was all against it. Look here, I want you to do something for me. The fact is, I’ve had a lot of expenses lately, with my twenty-firster and so on, and I’ve had rather to run up a few fairly warm bills here and there, so I shall probably have to touch the governor for a trifle over and above my allowance. What I want you to do is this: keep an eye on him, and if you notice that he’s particularly bucked about anything one day, wire to me first thing. Then I’ll run down and strike while the iron’s hot. See? Don’t forget.—Yours ever, Bob.

“P.S.—There’s just a chance that it may not be necessary after all. If everything goes well I may scrape into the ’Varsity team, and if I can manage to get my Blue he will be so pleased that a rabbit could feed out of his hand.”

I wrote back that afternoon, promising to do all I could. But I said that at present father was not feeling very happy, as London never agreed with him very well, and he might not like to be worried for money for a week or two. He does not mind what he gives us as a rule, but sometimes he seems to take a gloomy view of things, and talks about extravagance, and what a bad habit it is to develop in one’s youth, when one ought to be learning the value of money.

Bob replied that he understood, and added that a friend of his, who had it from another man who had lunched with a cousin of the secretary of football, had told him that they were thinking of giving him a trial soon in the team.

It was on the evening this letter came that Aunt Edith gave her ball. She is the nicest of my aunts, and was taking me about to places. I had been looking forward to this dance for weeks.

I wore my white satin with a pink sash, and a special person came in from Truefitt’s to do my hair. He was a restless little man, and talked to himself in French all the time. When he had finished he stepped back, and threw up his hands and said, “Ah, mademoiselle, c’est magnifique!”

I said, “Yes, isn’t it?”

It was, too.

I suppose different people have their different happiest moments. I expect father’s is when he makes a good stroke at cricket or shoots particularly well. And Bob has his, probably, when he kicks a football farther than anybody else. At least, I suppose so. I love cricket, but I don’t understand football. At any rate, I know when I feel happiest. It is when I know I look nice, and when the floor is just right and I have a partner whose step suits mine.

On this particular night everything was absolutely perfect. I looked very nice. I know one isn’t supposed to be aware of this, but father and Aunt Edith both told me, as well as at least half my partners, so there was a mass of corroborative evidence, as father says. Then the floor was lovely, and everybody seemed to dance well except one young man who had come from Cambridge for the ball. He danced very badly, but he did not seem to let it weigh upon his spirit at all. He was extremely cheerful.

“Would you prefer me,” he asked, “to apologize every time I tread on your foot, or shall I let it mount up and apologize collectively at the end?”

I suggested that we might sit out. He had no objection.

“As a matter of fact,” he said, “dancing’s good enough in its way, but footer’s my game.”

I said, “Oh!”

“Yes. Best game on earth, I think. I should like to play it all the year round. Cricket? Oh, yes, cricket’s good enough in its way, too. But it’s not a patch on footer. I was playing last week——”

My attention wandered.

“So you see,” he went on, “by half time neither side had scored. We had the wind with us in the second half, so——”

I could never understand football, so I am afraid I let my attention wander again. After some minutes I heard him say, “And so we won after all. Now, you can’t get that sort of thing at cricket.”

I said, “I suppose not.”

“Best game on earth, footer. I say, see that man who just passed us with the girl in red?”

I looked round. The man he referred to was my partner for the next dance. He was tall and wiry, and waltzed beautifully. He seemed a shy man. I noticed that he appeared to find a difficulty in talking to the lady in red. He looked troubled.

“See him?” said my companion.

I said I did.

“That’s Hook.”

“Yes; I remember that was his name.”

My companion seemed to miss something in my manner—surprise or admiration.

“The Hook, you know,” he added. “Captain of footer at Oxford. You must have heard of T. B. Hook!”

I didn’t like to say I had not; so I murmured, “Oh, T. B. Hook!”

This satisfied him. He went on to describe Mr. Hook.

“Best forward Oxford’s had for seasons. See him dribble—my word! Halloa! there’s the band starting again. May I take you——”

At this moment Mr. T. B. Hook detached himself—with relief, I thought—from the lady in red, and, after looking about him, caught sight of me and made his way in my direction. I admired the way he walked. He seemed to be on springs.

He danced splendidly, but in silence. After making one remark to him—about the floor—which caused him to look scared and crimson, I gave up the idea of conversation, and began to think, in a dreamy sort of way, in time to the music. It was not till quite the end of the dance that my great idea came to me. It came in a very roundabout way. First I thought about father, then about Bob, then about Bob’s letter, then about his saying he might play for Oxford. And then, quite in a flash, I realized that it was Mr. T. B. Hook, and no other, who had the power of letting him play or keeping him out, and I saw that here was my chance of doing Bob the good turn I owed him. I have since been told—by Bob—that an idea so awful (so absolutely fiendish, was his expression) could only have occurred to a girl. Ingratitude, as I have said before, is Bob’s besetting sin.

One of my aunts is always talking about the tremendous influence of a good woman. My idea was to try it, for Bob’s benefit, on Mr. T. B. Hook.

The music stopped, and we went into the conservatory. My partner’s silence was more noticeable now that we had stopped dancing. His waltzing had disguised it.

We sat down. I could feel him trying to find something to say. The only easy remark, about the floor, I had already made.

So I began.

I said, “You are very fond of football, aren’t you?”

He brightened up.

“Oh, yes,” he said. “Yes. Yes.”

He paused for a moment, then added, as if he had had an inspiration, “Yes.”

“Yes?” I said.

“Oh, yes,” he replied, brightly. “Yes.”

Our conversation was getting quite brisk and sparkling.

“You’re captain of Oxford, aren’t you?” I said.

“Oh, yes,” he replied. “Yes.”

“I’m very fond of cricket,” I said, “but I don’t understand football. I suppose it’s a very good game?”

“Oh, yes. Yes.”

“I have a brother who’s a very good player,” I went on.

“Yes?”

“Yes. He’s at Oxford, too. At Magdalen.”

“Yes?”

“Are you at Magdalen?”

“Trinity.”

“Do you know my brother?”

I saw he hadn’t heard my name when we had been introduced, so I added, “Romney.”

“I don’t think I know any Romney. But I don’t know many Magdalen men.”

“I thought you might, because he told me you were probably going to put him into the Oxford team. I do hope you will.”

Mr. Hook, who had been getting almost at home and at his ease, I believe, suddenly looked pink and scared again. I heard him whisper, “Good Lord!”

“Please put him in,” I went on, feeling like Bob’s guardian angel. “I’m sure he’s much better than anybody else, and we should be so pleased.”

“You would be so pleased,” he repeated, mechanically.

“Awfully pleased,” I said. “I couldn’t tell you how grateful. And it would make such a lot of difference to Bob. I can’t tell you why, but it would.”

“Oh, it would?” said he.

“A tremendous lot. You won’t forget the name, will you? Romney. I’ll write it down for you on your programme. R. Romney, Magdalen College. You will put him in, won’t you? I shall be too grateful for anything. And father——”

“I think this is ours?” said a voice.

My partner for the next dance was standing before me. In the ball-room they were just beginning the Eton boating-song. I heard Mr. Hook give a great sigh. It may have been sorrow, or it may have been relief.

About a week after this father said “Halloa!” as he was reading the paper at breakfast. “They’re playing Bob at half for Oxford, Joan,” he said, “against Wolverhampton Wanderers.”

“Oh, father!” I said; “are they really?”

The influence of the good woman had begun to work already.

“Instead of Welby-Smith, apparently. I suppose they had to make some changes after their poor show against the Casuals. Well, I hope Bob will stay in now he’s got there.”

“You’d be pleased if he got his Blue, wouldn’t you, father?”

“Yes, my dear, I should.”

I thought of writing to Mr. Hook to thank him, but decided not to. It was best to let well alone.

I got a letter from Bob a fortnight later saying that he was still in the team, though he had not been playing very well. He himself, he said, had rather fancied he would have been left out after the Old Malvernians’ match, and he wouldn’t have complained, because he had played badly; but for some reason they stuck to him, and if he didn’t do anything particularly awful in the next few matches, he said, he was practically a certainty for Queen’s Club.

“What’s Queen’s Club?” I asked father.

“It’s where the ’Varsity match is played. We must go and see it if Bob gets his Blue. Or in any case.”

Bob did get his Blue. I felt quite a thrill when I thought of what Mr. Hook had suffered for my sake. Because, you see, there were lots of people who thought Bob wasn’t good enough to be in the team. Father read me a bit out of a sporting paper in which the man who wrote it compared the two teams and said that “the weak spot in the Oxford side is undoubtedly Romney,” and a lot of horrid things about his not feeding his forwards properly. I said, “I’m sure that isn’t true. Bob’s always giving dinners to people. In fact, that’s the very reason why——”

I stopped.

“Why what?” said father.

“Why he’s so hard up, father, dear. He is, you know. It’s because of his twenty-first birthday, he said.”

“I shouldn’t wonder, my dear. I remember my own twenty-first birthday celebrations, and I don’t suppose things have altered much since my time. You must tell Bob to come to me if he is in difficulties. We mustn’t be hard on a man who’s playing in the ’Varsity match, eh, my dear?”

I said, “No; I’ll tell him.”

Bob stopped with us the night before the match. He hardly ate anything for dinner, and he wanted toast instead of bread. When I met him afterwards, though, he was looking very pleased with things and very friendly.

“It’s all right about those bills,” he said. “The governor has given me a cheque. He’s awfully bucked about my Blue.”

“And it was all me, Bob,” I cried. “It was every bit me. If it hadn’t been for me you wouldn’t be playing to-morrow. Aren’t you grateful, Bob? You ought to be.”

“If you can spare a moment and aren’t too busy talking rot,” said Bob, “you might tell me what it’s all about.”

“Why, it was through me you’ve got your Blue.”

“So I understand you to say. Mind explaining? Don’t, if it would give you a headache.”

“Why, I met the Oxford captain at Aunt Edith’s dance, and I said how anxious you were to get your Blue, and I begged him to put you in the team. And the very next Saturday you were tried for the first time.”

Bob positively reeled, and would have fallen had he not clutched a chair. I didn’t know people ever did it out of novels. He looked horrible. His mouth was wide open and his face a sort of pale green. He bleated like a sheep.

“Bob, don’t!” I said. “Whatever’s the matter?”

He recovered himself and laughed feebly. “All right, Kid,” he said, “that’s one to you. You certainly drew me then. By gad! I really thought you meant it at first.”

My eyes opened wide. “But, Bob,” I said, “I did.”

His jaw fell again.

“You mean to tell me,” he said slowly, “that you actually asked—— Oh, my aunt!”

He leaned his forehead on the mantelpiece.

“I shall have to go down,” he moaned. “I can’t stay up after this. Good Lord! the story may be all over the ’Varsity! Suppose somebody did get hold of it! I couldn’t live it down.”

He raised his head. “Look here, Joan,” he said; “if a single soul gets to hear of this I’ll never speak to you again.” And he stalked out of the room.

I sat down and cried.

He would hardly speak a word to me next morning. Father insisted on his having breakfast in bed, so as not to let him get tired; so I did not see him till lunch. After lunch we all drove off to Queen’s Club in Aunt Edith’s motor. While Bob was upstairs packing his bag, father said to me, “Here’s an honour for us, Joan. Bob is bringing the Oxford captain back to dinner to-night.”

I gasped. I felt it would take all my womanly tact to see me through the interview. He wouldn’t know how offended Bob was at being put in the team, and he might refer to our conversation at the dance.

Bob was evidently still wrapped in gloomy despair when he joined us. He was so silent in the motor that father thought he must be dreadfully nervous about the match, and tried to cheer him up, which made him worse. We arrived at the ground at last, and Bob went to the pavilion to change.

We sat just behind two young men whose whole appearance literally shrieked the word “Fresher”! When I thought that Bob had been just like that a year before and that he was really quite different now, I felt so proud of my efforts to improve him that I was quite consoled for the moment. I was in a gentle reverie when father nudged me, and I woke up to find that the two young men were discussing Bob. “Yes, that’s all very well,” one of them was saying, the one in the brighter brown suit, “but my point is that he’s too selfish. He doesn’t feed his forwards enough.”

I wondered whether this young man had been reading the sporting paper.

“He’s pretty nippy, though,” said the other.

“Personally, if I had been skipper,” said the bright brown one, “I should have played Welby-Smith. Why they ever chucked him licks me.”

“Well, I don’t know,” the other was beginning, when his words were drowned in a burst of applause, as the Cambridge team came on to the field. There was another shout a moment later, and Oxford appeared, Bob looking like a dog that’s just going to be washed.

“Good,” said the bright young man; “we’ve won the toss. The Tabs’ll have to play with the sun in their eyes second half. Just when it’s setting, too.”

I was glad to hear this, because I know what a nuisance the sun in one’s eyes is at cricket, and I suppose it must be just as bad at football.

There was a lot of running about and kicking at first. A little Cambridge man with light hair got the ball after a bit, and simply tore down the touch-line till he came to Bob, and Bob got in his way, and he kicked it to another man, only before he’d got it the other man who had been standing nearest to Bob at the beginning of the game took it away from him and sent it a long way up the field.

“Well played, Bob!” said father. “That little man with the light hair is Stevens, the international. He’s the most dangerous man Cambridge have got. Bob will have his work cut out to stop him. Still, he did it that time all right.”

The ball was being kicked about quite near the Cambridge goal now, so I thought Oxford must be getting the best of it. The little man was standing about by himself looking on, as if he were too important a person to mix himself up with the others. But suddenly one of the other Cambridge men sent the ball in his direction and he was off with it like a flash, and there seemed to be nobody there to stop him except Bob, who was jumping about half-way down the field.

All the Cambridge men raced down in the direction of the Oxford goal, and Bob met the little man as he had done before and made him pass to the other man. Then Bob rushed for this man, though there was another Oxford player rushing for him too, and the Cambridge man with the ball waited till they were both quite near him and then kicked it back to the international.

“Oh, Romney, you rotter!” said one of the young men in front of me, in a voice of agony; and then there was a perfect howl of joy from half the crowd, for the international, who hadn’t anyone between him and the goal but the goalkeeper, who looked nervous, ran round and shot the ball through into the net. “Well, there’s one of their goals,” said the not quite so bright young man. “Chap writing in the Chronicle this morning said Oxford would be lucky if they only had three scored against them. What a rotter Romney was to leave Stevens like that! Why on earth can’t he stick to his man?”

Father looked quite grey and haggard.

“If Bob’s going to play the fool like that,” he said, “he’d better have stayed at home.”

“What didn’t he do?” I asked.

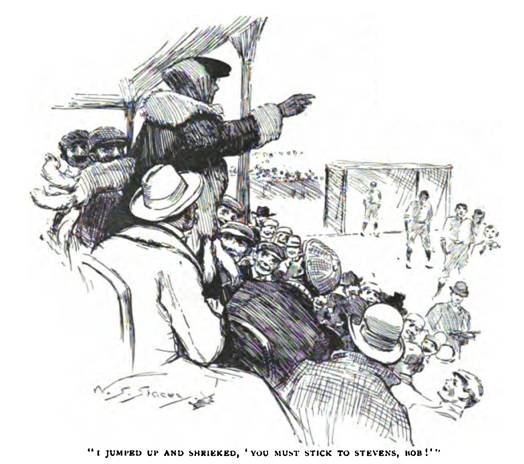

“He didn’t stick to his man. He gets up against an international forward, and the first thing he does is to leave him with a clear field. He must stick to Stevens.”

The whole air seemed full of Bob’s wrong-doing. I suppose it was a sort of wireless telegraphy or something that made me do it. At any rate, I jumped up and shrieked in front of everybody, in a dead silence, too: “You must stick to Stevens, Bob!”

Then there was a roar of laughter. I suppose it must have sounded funny, though I didn’t mean it; and everybody who wanted Oxford to win took up the cry. Only after shouting, “You must stick to Stevens, Bob!” once, they began to shout, “Buck up, Oxford!”

Bob turned scarlet—I was looking at him through father’s field-glasses—and I believe he was swearing to himself. Then the game began again.

Bob told me afterwards, in a calmer moment, that my cry was the turning-point. Up to then he had been fearfully ashamed of himself for letting the Cambridge man kick the ball away from him, but that now he felt that he must look so foolish that it was not worth while trying to realize it. He said he was like the girl in Shakespeare who smiled at grief. He had passed the limits of human feeling. The result was that he found himself suddenly icy cool, without nerves or anxiety or anything. He isn’t good at explaining his feelings, but I think I understand what he meant. I have felt it sometimes myself when, directly after I have had my best dress trodden on and torn at a dance, I have gone down to supper and found that all the meringues have been eaten. It is a sort of calm, divine despair. You know nothing else that can happen to you can be bad enough in comparison to be worth troubling about.

Anyhow, the result was that Bob began to play really splendidly. I can’t judge football at all, of course, but even I could see how good he was. He slipped about as if he were made of indiarubber. He sprang at Stevens and took the ball away from him. He kept kicking the ball back to the Cambridge goal. In fact, he thoroughly redeemed himself, and if it hadn’t been for the Cambridge goalkeeper Oxford would have scored any number of times. Just before half-time an Oxford man did score, so that made them level.

“Well, Romney’s done all right lately,” said one of the young men. “If he plays like that all the time we might win. What on earth he was doing at the start I can’t think.”

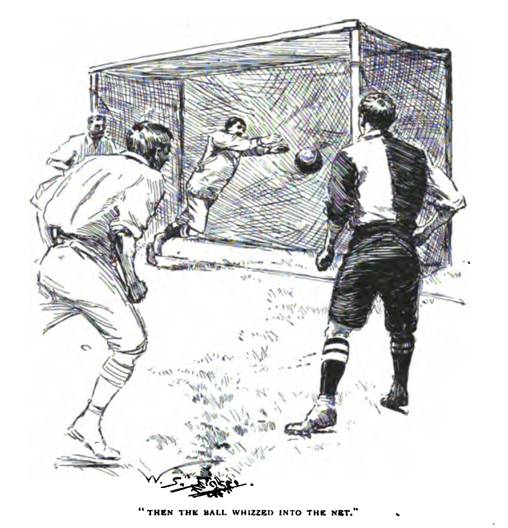

The sun was getting very low now, and Cambridge had to play facing it. It seemed to bother them a good deal, and Oxford kept on attacking, Bob coming up to help. At last, after they had been playing about twenty minutes, Stevens went off again, and Bob had to race back and stop him. He just managed to kick the ball over the touch-line. One of the Cambridge men picked it up and threw it in to another Cambridge man, but Bob suddenly darted between them, got the ball, and tore down the field. There were only two men in front of him besides the goalkeeper, and he wriggled past one of them, and father stood up and waved his hat and shouted instructions. Then the last Cambridge man bore down on him. It was thrilling. They were on the point of charging into one another when Bob kicked the ball to the left and ran to the right, and the Cambridge man shot past, and there was Bob in front of the goal just getting ready to shoot. Then the ball whizzed into the net, and all over the ground you could see hats flying into the air and sticks waving and a great roar went up from everywhere. It sounded like guns. “All the same,” said the bright brown young man, “he ought to have passed.”

Nothing more was scored, so Oxford just won.

The end was rather funny, because I know you are wondering what I said to Mr. Hook and what he said to me, and what Bob did. But it wasn’t a bit like what I had expected. When I came down to the drawing-room after dressing for dinner Bob and the captain were standing talking by the fire.

“I think you have met my sister already,” said Bob, dismally.

“I don’t think I’ve had the pleasure,” murmured the other man.

Bob turned to me.

“I thought you said you met Watson at Aunt Edith’s ball. So you were pulling my leg after all?”

“I didn’t. I wasn’t. I said I met the captain of the Oxford football team.”

“Well, that’s Watson.”

“Are you captain, really?” I asked.

“I’ve always been told so.”

“Then,” I said, “I think it’s my duty to tell you that there is a man called Hook—T. B. Hook—who goes about pretending he’s captain.”

“Hook of Oriel? Rather shy man? Doesn’t talk much?”

“Yes.”

“Oh, he’s captain of the Oxford Rugger team, you see. I’m captain of the Soccer,” said Mr. Watson.

“So it was Hook you asked?” said Bob. “Thank Heaven. You haven’t ruined my career, after all. Though I admit,” he added, kindly, “you did what you could.”

It is curious how everything seems to be all for the best. You would have thought that all my trouble had been wasted. But next day, to show his relief, Bob took me out and used some of father’s cheque in buying me the loveliest white “feathery” on earth; showing that out of evil cometh good, as our curate at home says.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums