The Strand Magazine, December 1924

THE pleasant morning sunshine descended like an amber shower-bath on Blandings Castle, that stately home of England which so adorns the county of Shropshire, lighting up with a heartening glow its ivied walls, its rolling parks, its gardens, outhouses, and messuages, and such of its inhabitants as chanced at the moment to be taking the air. It fell on green lawns and wide terraces, on noble trees and bright flower-beds. It fell on the baggy trousers-seat of Angus McAllister, head-gardener to the Earl of Emsworth, as he bent with dour Scottish determination to pluck a coy snail from its reverie beneath the leaf of a lettuce. It fell on the white flannels of the Hon. Freddie Threepwood, Lord Emsworth’s second son, hurrying across the water-meadows. It also fell on Lord Emsworth himself, for the proprietor of this fair domain was standing on the turret above the west wing, placidly surveying his possessions through a powerful telescope.

The Earl of Emsworth was a fluffy-minded and amiable old gentleman with a fondness for new toys. Although the main interest of his life was his garden, he was always ready to try a side-line; and the latest of these side-lines was this telescope of his—the outcome of a passion for astronomy which had lasted some two weeks.

For some minutes Lord Emsworth remained gazing with a pleased eye at a cow down in the meadows. It was a fine cow as cows go, but, like so many cows, it lacked sustained dramatic interest; and his lordship, surfeited after awhile by the spectacle of it chewing the cud and staring glassily at nothing, was about to swivel the apparatus round in the hope of picking up something a trifle more sensational, when into the range of his vision there came the Hon. Freddie. White and shining, he tripped along over the turf like a Theocritan shepherd hastening to keep an appointment with a nymph; and for the first time that morning a frown came to mar the serenity of Lord Emsworth’s brow. He generally frowned when he saw Freddie, for with the passage of the years that youth had become more and more of a problem to an anxious father.

The Earl of Emsworth, like so many of Britain’s aristocracy, had but little use for the younger son. And Freddie Threepwood was a particularly trying younger son. There seemed, in the opinion of his nearest and dearest, to be no way of coping with the boy. If he was allowed to live in London, he piled up debts and got into mischief; and when hauled back home to Blandings, he moped broodingly. It was possibly the fact that his demeanour at this moment was so mysteriously jaunty, his bearing so inexplicably free from the crushed misery with which he usually mooned about the place, that induced Lord Emsworth to keep a telescopic eye on him. Some inner voice whispered to him that Freddie was up to no good and would bear watching.

The inner voice was absolutely correct. Within thirty seconds its case had been proved up to the hilt. Scarcely had his lordship had time to wish, as he invariably wished on seeing his offspring, that Freddie had been something entirely different in manners, morals, and appearance, and had been the son of somebody else living a considerable distance away, when out of a small spinney near the end of the meadow there bounded a girl. And Freddie, after a cautious glance over his shoulder, immediately proceeded to fold this female in a warm embrace.

LORD EMSWORTH had seen enough. He tottered away from the telescope, a shattered man. One of his favourite dreams was of some nice, eligible girl, belonging to a good family and possessing a bit of money of her own, coming along some day and taking Freddie off his hands; but that inner voice, more confident now than ever, told him that this was not she. Freddie would not sneak off in this furtive fashion to meet eligible girls, nor could he imagine any eligible girl, in her right senses, rushing into Freddie’s arms in that enthusiastic way. No, there was only one explanation. In the cloistral seclusion of Blandings, far from the Metropolis with all its conveniences for that sort of thing, Freddie had managed to get himself entangled. Seething with anguish and fury, Lord Emsworth hurried down the stairs and out on to the terrace. Here he prowled like an elderly leopard waiting for feeding-time, until in due season there was a flicker of white among the trees that flanked the drive and a cheerful whistling announced the culprit’s approach.

It was with a sour and hostile eye that Lord Emsworth watched his son draw near. He adjusted his pince-nez, and with their assistance was able to perceive that a fatuous smile of self-satisfaction illumined the young man’s face, giving him the appearance of a beaming sheep. In the young man’s buttonhole there shone a nosegay of simple meadow-flowers, which, as he walked, he patted from time to time with a loving hand.

“Frederick!” bellowed his lordship.

The villain of the piece halted abruptly. Sunk in a roseate trance, he had not observed his father. But such was the sunniness of his mood that even this encounter could not damp him. He gambolled happily up.

“Hullo, guv’nor!” he carolled. He searched in his mind for a pleasant topic of conversation—always a matter of some little difficulty on these occasions. “Lovely day, what?”

His lordship was not to be diverted into a discussion of the weather. He drew a step nearer, looking like the man who smothered the young princes in the Tower.

“Frederick,” he demanded, “who was that girl?”

The Hon. Freddie started convulsively. He appeared to be swallowing with difficulty something large and jagged.

“Girl?” he quavered. “Girl? Girl, guv’nor?”

“That girl I saw you kissing ten minutes ago down in the water-meadows.”

“Oh!” said the Hon. Freddie. He paused. “Oh, ah!” He paused again. “Oh, ah, yes! I’ve been meaning to tell you about that, guv’nor.”

“You have, have you?”

“All perfectly correct, you know. Oh, yes, indeed! All most absolutely correct-o! Nothing fishy, I mean to say, or anything like that. She’s my fiancée.”

A sharp howl escaped Lord Emsworth, as if one of the bees humming in the lavender-beds had taken time off to sting him in the neck.

“Who is she?” he boomed. “Who is this woman?”

“Her name’s Donaldson.”

“Who is she?”

“Aggie Donaldson. Aggie’s short for Niagara. Her people spent their honeymoon at the Falls, she tells me. She’s American and all that. Rummy names they give kids in America,” proceeded Freddie, with hollow chattiness. “I mean to say! Niagara! I ask you!”

“Who is she?”

“She’s most awfully bright, you know. Full of beans. You’ll love her.”

“Who is she?”

“And can play the saxophone.”

“Who,” demanded Lord Emsworth for the sixth time, “is she? And where did you meet her?”

Freddie coughed. The information, he perceived, could no longer be withheld, and he was keenly alive to the fact that it scarcely fell into the class of tidings of great joy.

“Well, as a matter of fact, guv’nor, she’s a sort of cousin of Angus McAllister’s. She’s come over to England for a visit, don’t you know, and is staying with the old boy. That’s how I happened to run across her.”

Lord Emsworth’s eyes bulged and he gargled faintly. He had had many unpleasant visions of his son’s future, but they had never included one of him walking down the aisle with a sort of cousin of his head-gardener.

“Oh!” he said. “Oh, indeed?”

“That’s the strength of it, guv’nor.”

Lord Emsworth threw his arms up, as if calling on Heaven to witness a good man’s persecution, and shot off along the terrace at a rapid trot. Having ranged the grounds for some minutes, he ran his quarry to earth at the entrance to the yew alley.

The head-gardener turned at the sound of his footsteps. He was a sturdy man of medium height, with eyebrows that would have fitted better a bigger forehead. These, added to a red and wiry beard, gave him a formidable and uncompromising expression. Honesty Angus McAllister’s face had in full measure, and also intelligence; but it was a bit short on sweetness and light.

“McAllister,” said his lordship, plunging without preamble into the matter of his discourse. “That girl. You must send her away.”

A look of bewilderment clouded such of Mr. McAllister’s features as were not concealed behind his beard and eyebrows.

“Gurrul?”

“That girl who is staying with you. She must go!”

“Gae where?”

Lord Emsworth was not in the mood to be finicky about details.

“Anywhere,” he said. “I won’t have her here a day longer.”

“Why?” inquired Mr. McAllister, who liked to thresh these things out.

“Never mind why. You must send her away immediately.”

Mr. McAllister mentioned an insuperable objection.

“She’s payin’ me twa poon’ a week,” he said, simply.

Lord Emsworth did not grind his teeth, for he was not given to that form of displaying emotion; but he leaped some ten inches into the air and dropped his pince-nez. And, though normally a fair-minded and reasonable man, well aware that modern earls must think twice before pulling the feudal stuff on their employés, he took on the forthright truculence of a large landowner of the early Norman period ticking off a serf.

“Listen, McAllister! Listen to me! Either you send that girl away to-day or you can go yourself. I mean it!”

A curious expression came into Angus McAllister’s face—always excepting the occupied territories. It was the look of a man who has not forgotten Bannockburn, a man conscious of belonging to the country of William Wallace and Robert the Bruce. He made Scotch noises at the back of his throat.

“Y’r lorrudsheep will accept ma notis,” he said, with formal dignity.

“I’ll pay you a month’s wages in lieu of notice and you will leave this afternoon,” retorted Lord Emsworth with spirit.

“Mphm!” said Mr. McAllister.

Lord Emsworth left the battlefield with a feeling of pure exhilaration, still in the grip of the animal fury of conflict. No twinge of remorse did he feel at the thought that Angus McAllister had served him faithfully for ten years. Nor did it cross his mind that he might miss McAllister.

But that night, as he sat smoking his after-dinner cigarette, Reason, so violently expelled, came stealing timidly back to her throne, and a cold hand seemed suddenly placed upon his heart.

With Angus McAllister gone, how would the pumpkin fare?

THE importance of this pumpkin in the Earl of Emsworth’s life requires, perhaps, a word of explanation. Every ancient family in England has some little gap in its scroll of honour, and that of Lord Emsworth was no exception. For generations back his ancestors had been doing notable deeds: they had sent out from Blandings Castle statesmen and warriors, governors and leaders of the people: but they had not—in the opinion of the present holder of the title—achieved a full hand. However splendid the family record might appear at first sight, the fact remained that no Earl of Emsworth had ever won a first prize for pumpkins at the Shrewsbury Flower and Vegetable Show. For roses, yes. For tulips, true. For spring onions, granted. But not for pumpkins; and Lord Emsworth felt it deeply.

For many a summer past he had been striving indefatigably to remove this blot on the family escutcheon, only to see his hopes go tumbling down. But this year at last victory had seemed in sight, for there had been vouchsafed to Blandings a competitor of such amazing parts that his lordship, who had watched it grow practically from a pip, could not envisage failure. Surely, he told himself as he gazed on its golden roundness, even Sir Gregory Parsloe-Parsloe, of Badgwick Hall, winner for three successive years, would never be able to produce anything to challenge this superb vegetable.

And it was this supreme pumpkin whose welfare he feared he had jeopardized by dismissing Angus McAllister. For Angus was its official trainer. He understood the pumpkin. Indeed, in his reserved Scottish way, he even seemed to love it. With Angus gone, what would the harvest be?

SUCH were the meditations of Lord Emsworth as he reviewed the position of affairs. And though, as the days went by, he tried to tell himself that Angus McAllister was not the only man in the world who understood pumpkins, and that he had every confidence, the most complete and unswerving confidence, in Robert Barker, recently Angus’s second-in-command, now promoted to the post of head-gardener and custodian of the Blandings Hope, he knew that this was but shallow bravado. When you are a pumpkin-owner with a big winner in your stable, you judge men by hard standards, and every day it became plainer that Robert Barker was only a makeshift. Within a week Lord Emsworth was pining for Angus McAllister.

It might be purely imagination, but to his excited fancy the pumpkin seemed to be pining for Angus too. It appeared to be drooping and losing weight. Lord Emsworth could not rid himself of the horrible idea that it was shrinking. And on the tenth night after McAllister’s departure he dreamed a strange dream. He had gone with King George to show his Gracious Majesty the pumpkin, promising him the treat of a lifetime; and, when they arrived, there in the corner of the frame was a shrivelled thing the size of a pea. He woke, sweating, with his sovereign’s disappointed screams ringing in his ears; and Pride gave its last quiver and collapsed. To reinstate Angus would be a surrender, but it must be done.

“Beach,” he said that morning at breakfast, “do you happen to—er—to have McAllister’s address?”

“Yes, your lordship,” replied the butler. “He is in London, residing at number eleven Buxton Crescent.”

“Buxton Crescent? Never heard of it.”

“It is, I fancy, your lordship, a boarding-house or some such establishment off the Cromwell Road. McAllister was accustomed to make it his head-quarters whenever he visited the Metropolis on account of its handiness for Kensington Gardens. He liked,” said Beach with respectful reproach, for Angus had been a friend of his for nine years, “to be near the flowers, your lordship.”

TWO telegrams, passing through it in the course of the next twelve hours, caused some gossip at the post-office of the little town of Market Blandings.

The first ran:—

McAllister,

11, Buxton Crescent,

Cromwell Road,

London.

Return immediately.—Emsworth.

The second:—

Lord Emsworth,

Blandings Castle,

Shropshire.

I will not.—McAllister.

Lord Emsworth had one of those minds capable of accommodating but one thought at a time—if that; and the possibility that Angus McAllister might decline to return had not occurred to him. It was difficult to adjust himself to this new problem, but he managed it at last. Before nightfall he had made up his mind. Robert Barker, that broken reed, could remain in charge for another day or so, and meanwhile he would go up to London and engage a real head-gardener, the finest head-gardener that money could buy.

IT was the opinion of Dr. Johnson that there is in London all that life can afford. A man, he held, who is tired of London is tired of life itself. Lord Emsworth, had he been aware of this statement, would have contested it warmly. He hated London. He loathed its crowds, its smells, its noises; its omnibuses, its taxis, and its hard pavements. And, in addition to all its other defects, the miserable town did not seem able to produce a single decent head-gardener. He went from agency to agency, interviewing candidates, and not one of them came within a mile of meeting his requirements. He disliked their faces, he distrusted their references. It was a harsh thing to say of any man, but he was dashed if the best of them was even as good as Robert Barker.

It was, therefore, in a black and soured mood that his lordship, having lunched frugally at the Senior Conservative Club on the third day of his visit, stood on the steps in the sunshine, wondering how on earth he was to get through the afternoon. He had spent the morning rejecting head-gardeners, and the next batch was not due until the morrow. And what—besides rejecting head-gardeners—was there for a man of reasonable tastes to do with his time in this hopeless town?

And then there came into his mind a remark which Beach the butler had made at the breakfast-table about flowers in Kensington Gardens. He could go to Kensington Gardens and look at the flowers.

He was about to hail a taxi-cab from the rank down the street when there suddenly emerged from the Hotel Magnificent over the way a young man. This young man proceeded to cross the road, and, as he drew near, it seemed to Lord Emsworth that there was about his appearance something oddly familiar. He stared for a long instant before he could believe his eyes, then with a wordless cry bounded down the steps just as the other started to mount them.

“Oh, hullo, guv’nor!” ejaculated the Hon. Freddie, plainly startled.

“What—what are you doing here?” demanded Lord Emsworth.

He spoke with heat, and justly so. London, as the result of several spirited escapades which still rankled in the mind of a father who had had to foot the bills, was forbidden ground to Freddie.

The young man was plainly not at his ease. He had the air of one who is being pushed towards dangerous machinery in which he is loath to become entangled. He shuffled his feet for a moment, then raised his left shoe and rubbed the back of his right calf with it.

“The fact is, guv’nor——”

“You know you are forbidden to come to London.”

“Absolutely, guv’nor, but the fact is——”

“And why anybody but an imbecile should want to come to London when he could be at Blandings——”

“I know, guv’nor, but the fact is——” Here Freddie, having replaced his wandering foot on the pavement, raised the other, and rubbed the back of his left calf. “I wanted to see you,” he said. “Yes. Particularly wanted to see you.”

This was not strictly accurate. The last thing in the world which the Hon. Freddie wanted was to see his parent. He had come to the Senior Conservative Club to leave a carefully written note. Having delivered which, it had been his intention to bolt like a rabbit. This unforeseen meeting had upset his plans.

“To see me?” said Lord Emsworth. “Why?”

“Got—er—something to tell you. Bit of news.”

“I trust it is of sufficient importance to justify your coming to London against my express wishes.”

“Oh, yes. Oh, yes, yes-yes. Oh, rather. It’s dashed important. Yes—not to put too fine a point upon it—most dashed important. I say, guv’nor, are you in fairly good form to stand a bit of a shock?”

A ghastly thought rushed into Lord Emsworth’s mind. Freddie’s mysterious arrival—his strange manner—his odd hesitation and uneasiness—could it mean——? He clutched the young man’s arm feverishly.

“Frederick! Speak! Tell me! Have the cats got at it?”

It was a fixed idea of Lord Emsworth, which no argument would have induced him to abandon, that cats had the power to work some dreadful mischief on his pumpkin and were continually lying in wait for the opportunity of doing so; and his behaviour on the occasion when one of the fast sporting set from the stables, wandering into the kitchen-garden and finding him gazing at the Blandings Hope, had rubbed itself sociably against his leg, lingered long in that animal’s memory.

Freddie stared.

“Cats? Why? Where? Which? What cats?”

“Frederick! Is anything wrong with the pumpkin?”

In a crass and materialistic world there must inevitably be a scattered few here and there in whom pumpkins touch no chord. The Hon. Freddie Threepwood was one of these. He was accustomed to speak in mockery of all pumpkins, and had even gone so far as to allude to the Hope of Blandings as “Percy.” His father’s anxiety, therefore, merely caused him to giggle.

“Not that I know of,” he said.

“Then what do you mean?” thundered Lord Emsworth, stung by the giggle. “What do you mean, sir, by coming here and alarming me—scaring me out of my wits, by Gad!—with your nonsense about giving me shocks?”

The Hon. Freddie looked carefully at his fermenting parent. His fingers, sliding into his pocket, closed on the note which nestled there. He drew it forth.

“Look here, guv’nor,” he said, nervously. “I think the best thing would be for you to read this. Meant to leave it for you with the hall-porter. It’s—well, you just cast your eyes over it. Good-bye, guv’nor. Got to see a man.”

And, thrusting the note into his father’s hand, the Hon. Freddie turned and was gone. Lord Emsworth, perplexed and annoyed, watched him skim up the road and leap into a cab. He seethed impotently. Practically any behaviour on the part of his son Frederick had the power to irritate him, but it was when he was vague and mysterious and incoherent that the young man irritated him most.

He looked at the letter in his hand, turned it over, felt it, and even smelt it. Then—for it had suddenly occurred to him that if he wished to ascertain its contents he had better read it—he tore open the envelope.

The note was brief, but full of good reading matter.

Dear Guv’nor,

Awfully sorry and all that, but couldn’t hold out any longer. I’ve popped up to London in the two-seater and Aggie and I were spliced this morning. There looked like being a bit of a hitch at one time, but Aggie’s guv’nor, who has come over from America, managed to wangle it all right by getting a special licence or something of that order. A most capable Johnny. He’s coming to see you. He wants to have a good long talk with you about the whole binge. Lush him up hospitably and all that, would you mind, because he’s a really sound egg, and you’ll like him.

Well, cheerio!

Your affectionate son,

Freddie.

P.S.—You won’t mind if I freeze on to the two-seater for the nonce, what? It may come in useful for the honeymoon.

The Senior Conservative Club is a solid and massive building, but, as Lord Emsworth raised his eyes dumbly from the perusal of this letter, it seemed to him that it was performing a kind of whirling dance. The whole of the immediate neighbourhood, indeed, appeared to be shimmying in the middle of a thick mist. He was profoundly stirred. It is not too much to say that he was shaken to the core of his being. No father enjoys being flouted and defied by his own son; nor is it reasonable to expect a man to take a cheery view of life who is faced with the prospect of supporting for the remainder of his years a younger son, a younger son’s wife, and possible younger grandchildren.

For an appreciable space of time he stood in the middle of the pavement, rooted to the spot. Passers-by bumped into him or grumblingly made détours to avoid a collision. Dogs sniffed at his ankles. Seedy-looking individuals tried to arrest his attention in order to speak of their financial affairs. Lord Emsworth heeded none of them. He remained where he was, gaping like a fish, until suddenly his faculties seemed to return to him.

An imperative need for flowers and green trees swept upon Lord Emsworth. The noise of the traffic and the heat of the sun on the stone pavement were afflicting him like a nightmare. He signalled energetically to a passing cab.

“Kensington Gardens,” he said, and sank back on the cushioned seat.

SOMETHING dimly resembling peace crept into his lordship’s soul as he paid off his cab and entered the cool shade of the gardens. Even from the road he had caught a glimpse of stimulating reds and yellows; and as he ambled up the asphalt path and plunged round the corner the flower-beds burst upon his sight in all their consoling glory.

“Ah!” breathed Lord Emsworth, rapturously, and came to a halt before a glowing carpet of tulips. A man of official aspect, wearing a peaked cap and a uniform, stopped as he heard the exclamation and looked at him with approval and even affection.

“Nice weather we’re ’avin’,” he observed.

Lord Emsworth did not reply. He had not heard. There is that about a well-set-out bed of flowers which acts on men who love their gardens like a drug, and he was in a sort of trance. Already he had completely forgotten where he was, and seemed to himself to be back in his paradise of Blandings. He drew a step nearer to the flower-bed, pointing like a setter.

The official-looking man’s approval deepened. This man with the peaked cap was the park-keeper, who held the rights of the high, the low, and the middle justice over that section of the gardens. He, too, loved these flower-beds, and he seemed to see in Lord Emsworth a kindred soul. The general public was too apt to pass by, engrossed in its own affairs, and this often wounded the park-keeper. In Lord Emsworth he thought that he recognized one of the right sort.

“Nice——” he began.

He broke off with a sharp cry. If he had not seen it with his own eyes, he would not have believed it. But, alas, there was no possibility of a mistake. With a ghastly shock he realized that he had been deceived in this attractive stranger. Decently, if untidily, dressed; clean; respectable to the outward eye; the stranger was in reality a dangerous criminal, the blackest type of evil-doer on the park-keeper’s index. He was a Kensington Gardens flower-picker.

For, even as he uttered the word “Nice,” the man had stepped lightly over the low railing, had shambled across the strip of turf, and before you could say “knife” was busy on his dark work. In the brief instant in which the park-keeper’s vocal chords refused to obey him, he was two tulips ahead of the game and reaching out to scoop in a third.

“Hi!!!” roared the park-keeper, suddenly finding speech. “ ’I there!!!”

Lord Emsworth turned with a start.

“Bless my soul!” he murmured, reproachfully.

He was in full possession of his senses now, such as they were, and understood the enormity of his conduct. He shuffled back on to the asphalt, contrite.

“My dear fellow——” he began, remorsefully.

The park-keeper began to speak rapidly and at length. From time to time Lord Emsworth moved his lips and made deprecating gestures, but he could not stem the flood. Louder and more rhetorical grew the park-keeper and denser and more interested the rapidly assembling crowd of spectators. And then through the stream of words another voice spoke.

“Wot’s all this?”

The Force had materialized in the shape of a large, solid constable.

The park-keeper seemed to understand that he had been superseded. He still spoke, but no longer like a father rebuking an erring son. His attitude now was more that of an elder brother appealing for justice against a delinquent junior. In a moving passage he stated his case.

“ ’E Says,” observed the constable, judicially, speaking slowly and in capitals, as if addressing an untutored foreigner, “ ’E Says You Was Pickin’ The Flowers.”

“I saw ’im. I was standin’ as close as I am to you.”

“ ’E Saw You,” interpreted the constable. “ ’E Was Standing At Your Side.”

Lord Emsworth was feeling weak and bewildered. Without a thought of annoying or doing harm to anybody, he seemed to have unchained the fearful passions of a French Revolution; and there came over him a sense of how unjust it was that this sort of thing should be happening to him, of all people—a man already staggering beneath the troubles of a Job.

“I’ll ’ave to ask you for your name and address,” said the constable, more briskly. A stubby pencil popped for an instant into his stern mouth and hovered, well and truly moistened, over the virgin page of his notebook—that dreadful notebook before which taxi-drivers shrink and hardened bus-conductors quail.

“I—I—why, my dear fellow—I mean, officer—I am the Earl of Emsworth.”

Much has been written of the psychology of crowds, designed to show how extraordinary and inexplicable it is, but most of such writing is exaggeration. A crowd generally behaves in a perfectly natural and intelligible fashion. When, for instance, it sees a man in a badly-fitting tweed suit and a hat he ought to be ashamed of getting put through it for pinching flowers in the Park, and the man says he is an earl, it laughs. This crowd laughed.

“Ho?” The constable did not stoop to join in the merriment of the rabble, but his lip twitched sardonically. “Have you a card, your lordship?”

Nobody intimate with Lord Emsworth would have asked such a foolish question. His card-case was the thing he always lost second when visiting London—immediately after losing his umbrella.

“I—er—I’m afraid——”

“R!” said the constable. And the crowd uttered another happy, hyena-like laugh, so intensely galling that his lordship raised his bowed head and found enough spirit to cast an indignant glance. And, as he did so, the hunted look faded from his eyes.

“McAllister!” he cried.

Two new arrivals had just joined the throng, and, being of rugged and nobbly physique, had already shoved themselves through to the ringside seats. One was a tall, handsome, smooth-faced gentleman of authoritative appearance, who, if he had not worn rimless glasses, would have looked like a Roman emperor. The other was a shorter, sturdier man with a bristly red beard.

“McAllister!” moaned his lordship, piteously. “McAllister, my dear fellow, do please tell this man who I am.”

After what had passed between himself and his late employer, a lesser man than Angus McAllister might have seen in Lord Emsworth’s predicament merely a judgment. A man of little magnanimity would have felt that here was where he got a bit of his own back.

Not so this splendid Glaswegian.

“Aye,” he said. “Yon’s Lorrud Emsworruth.”

“Who are you?” inquired the constable, searchingly.

“I used to be head-gardener at the cassel.”

“Exactly,” bleated Lord Emsworth. “Precisely. My head-gardener.”

The constable was shaken. Lord Emsworth might not look like an earl, but there was no getting away from the fact that Angus McAllister was supremely head-gardeneresque. A staunch admirer of the aristocracy, the constable perceived that zeal had caused him to make a bit of a bloomer. Yes, he had dropped a brick.

In this crisis, however, he comported himself with a masterly tact. He scowled blackly upon the interested throng.

“Pass along there, please. Pass along,” he commanded, austerely. “Ought to know better than block up a public thoroughfare like this. Pass along!”

He moved off, shepherding the crowd before him. The Roman emperor with the rimless glasses advanced upon Lord Emsworth, extending a large hand.

“Pleased to meet you at last,” he said. “My name is Donaldson, Lord Emsworth.”

For a moment the name conveyed nothing to his lordship. Then its significance hit him, and he drew himself up with hauteur.

“You’ll excuse us, Angus,” said Mr. Donaldson. “High time you and I had a little chat, Lord Emsworth.”

LORD EMSWORTH was about to speak, when he caught the other’s eye. It was a strong, keen, level grey eye, with a curious forcefulness about it that made him feel strangely inferior. There is every reason to suppose that Mr. Donaldson had subscribed for years to those personality courses advertised in the magazines which guarantee to impart to the pupil who takes ten correspondence lessons the ability to look the boss in the eye and make him wilt. Mr. Donaldson looked Lord Emsworth in the eye, and Lord Emsworth wilted.

“How do you do?” he said, weakly,

“Now listen, Lord Emsworth,” proceeded Mr. Donaldson. “No sense in having hard feelings between members of a family. I take it you’ve heard by this that your boy and my girl have gone ahead and fixed it up? Personally, I’m delighted. That boy is a fine young fellow.”

Lord Emsworth blinked.

“You are speaking of my son Frederick?” he said, incredulously.

“Of your son Frederick. Now, at the moment, no doubt, you are feeling a trifle sore. I don’t blame you. You have every right to be sorer than a gumboil. But you must remember—young blood, eh? It will, I am convinced, be a lasting grief to that splendid young man——”

“You are still speaking of my son Frederick?”

“Of Frederick, yes. It will, I say, be a lasting grief to him if he feels he has incurred your resentment. You must forgive him, Lord Emsworth. He must have your support.”

“I suppose he’ll have to have it, dash it!” said his lordship, unhappily. “Can’t let the boy starve.”

Mr. Donaldson’s hand swept round in a wide, grand gesture.

“Don’t you worry about that. I’ll look after that end of it. I am not a rich man——”

“Ah!” said his lordship, resignedly. A faint hope, inspired by the largeness of the other’s manner, had been flickering in his bosom.

“I doubt,” continued Mr. Donaldson, frankly, “if, all told, I have as much as ten million dollars in the world.”

Lord Emsworth swayed like a sapling in the breeze.

“Ten million? Ten million? Did you say you had ten million dollars?”

“Between nine and ten, I suppose. Not more. But you must bear in mind that the business is growing all the time. I am Donaldson’s Dog-Biscuits.”

“Donaldson’s Dog-Biscuits! Indeed! Really! Fancy that!”

“You have heard of them?” asked Mr. Donaldson, eagerly.

“Never,” said Lord Emsworth, cordially.

“Oh! Well, that’s who I am. And, with your approval, I intend to send Frederick over to Long Island City to start learning the business. I have no doubt that he will in time prove a most valuable asset to the firm.”

Lord Emsworth could conceive of no way in which Freddie could be of value to a dog-biscuit firm, except possibly as a taster; but he refrained from damping the other’s enthusiasm by saying so.

“He seems full of keenness. But he must feel that he has your moral support, Lord Emsworth—his father’s moral support.”

“Yes, yes, yes!” said Lord Emsworth, heartily. A feeling of positive adoration for Mr. Donaldson was thrilling him. The getting rid of Freddie, which he himself had been unable to achieve in twenty-six years, this godlike dog-biscuit manufacturer had accomplished in less than a week. “Oh, yes, yes, yes! Yes, indeed! Most decidedly!”

“They sail on Wednesday.”

“Splendid!”

“Early in the morning.”

“Capital!”

“I may give them a friendly message from you?”

“Certainly! Certainly, certainly, certainly! Inform Frederick that he has my best wishes.”

“I will.”

“Mention that I shall watch his future progress with considerable interest.”

“Exactly.”

“Say that I hope he will work hard and make a name for himself.”

“Just so.”

“And,” concluded Lord Emsworth, speaking with a fatherly earnestness well in keeping with this solemn moment, “tell him—er—not to hurry home.”

He pressed Mr. Donaldson’s hand with feelings too deep for further speech. Then he galloped swiftly to where Angus McAllister stood brooding over the tulip-bed.

“McAllister!”

The other’s beard waggled grimly. He looked at his late employer with cold eyes.

“McAllister,” faltered Lord Emsworth, humbly, “I wish—I wonder—— What I want to say is, have you accepted another situation yet?”

“I am conseederin’ twa.”

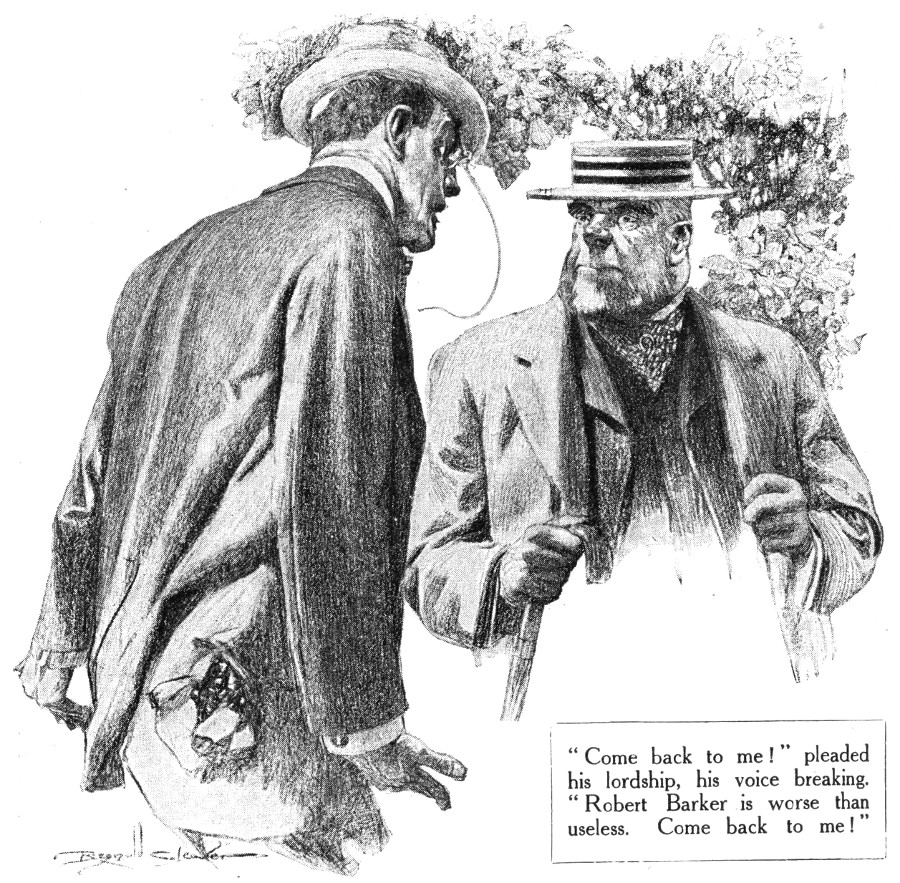

“Come back to me!” pleaded his lordship, his voice breaking. “Robert Barker is worse than useless. Come back to me!”

Angus McAllister gazed woodenly at the tulips.

“A’ weel——” he said at length.

“You will?” cried Lord Emsworth, joyfully. “Splendid! Capital! Excellent!”

“A’ didna say I wud.”

“I thought you said ‘I will,’ ” said his lordship, dashed.

“I didna say ‘A’ weel,’ I said ‘A’ weel,’ ” said Mr. McAllister, stiffly. “Meanin’ mebbe I might, mebbe not.”

Lord Emsworth laid a trembling hand upon his arm.

“McAllister, I will raise your salary.”

The beard twitched.

“Dash it, I’ll double it!”

The eyebrows flickered.

“McAllister—Angus,” said Lord Emsworth, in a low voice. “Come back! The pumpkin needs you.”

IN an age of rush and hurry like that of to-day, an age in which there are innumerable calls on the leisure-time of everyone, it is possible that here and there throughout the ranks of the public who have read this chronicle there may be one or two who for various reasons found themselves unable to attend the annual Flower and Vegetable Show at Shrewsbury. Sir Gregory Parsloe-Parsloe, of Badgwick Hall, was there, of course, but it would not have escaped the notice of a close observer that his mien lacked something of the haughty arrogance which had characterized it in other years. From time to time, as he paced the tent devoted to the exhibition of vegetables, he might have been seen to bite his lip, and his eye had something of that brooding look which Napoleon’s must have worn after Waterloo.

But there is the right stuff in Sir Gregory. He is a gentleman and a sportsman. In the Parsloe-Parsloe tradition there is nothing small or mean. Half-way down the tent he stopped, and with a quick, manly gesture thrust out his hand.

“Congratulate you, Emsworth,” he said, huskily.

Lord Emsworth looked up with a start. He had been deep in his thoughts.

“Thanks, my dear fellow. Thanks. Thanks. Thank you very much.” He hesitated. “Er—can’t both win, if you understand me.”

Sir Gregory puzzled it out.

“No,” he said. “No. See what you mean. Can’t both win.” He nodded and walked on, with who knows what vultures gnawing at his broad bosom. And Lord Emsworth—with Angus McAllister, who had been a silent witness of the scene, at his side—turned once more to stare reverently at that which lay on the strawy bottom of one of the largest packing-cases ever seen in Shrewsbury town.

Inside it something vast and golden beamed up at him.

A card had been attached to the exterior of the packing-case. It bore the simple legend:—

PUMPKINS. FIRST PRIZE.

Compare the American magazine version from the Saturday Evening Post, November 29, 1924.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums