The Strand Magazine, May 1927

MISS POSTLETHWAITE, our courteous and vigilant barmaid, had whispered to us that the gentleman sitting over there in the corner was an American gentleman.

“Comes from America,” added Miss Postlethwaite, making her meaning clearer.

“From America?” echoed we.

“From America,” said Miss Postlethwaite. “He’s an American.”

Mr. Mulliner rose with an old-world grace. We do not often get Americans in the bar-parlour of the Angler’s Rest. When we do, we welcome them. We make them realize that Hands Across the Sea is no mere phrase.

“Good evening, sir,” said Mr. Mulliner. “I wonder if you would care to join my friend and myself in a little refreshment?”

“Very kind of you, sir.”

“Miss Postlethwaite, the usual. I understand you are from the other side, sir. Do you find our English countryside pleasant?”

“Delightful. Though, of course, if I may say so, scarcely to be compared with the scenery of my home State.”

“What State is that?”

“California,” replied the other, baring his head. “California, the Jewel State of the Union. With its azure sea, its noble hills, its eternal sunshine, and its fragrant flowers, California stands alone. Peopled by stalwart men and womanly women——”

“California would be all right,” said Mr. Mulliner, “if it wasn’t for the earthquakes.”

Our guest started as though some venomous snake had bitten him.

“Earthquakes are absolutely unknown in California,” he said, hoarsely.

“What about the one in 1907?”

“That was not an earthquake. It was a fire.”

“An earthquake, I always understood,” said Mr. Mulliner. “My Uncle William was out there during it, and many a time has he said to me, ‘My boy, it was the San Francisco earthquake that won me a bride.’ ”

“Couldn’t have been the earthquake. May have been the fire.”

“Well, I will tell you the story, and you shall judge for yourself.”

“I shall be glad to hear your story about the San Francisco fire,” said the Californian, courteously.

MY Uncle William (said Mr. Mulliner) was returning from the East at the time. The commercial interests of the Mulliners have always been far-flung: and he had been over in China looking into the workings of a tea-exporting business in which he held a number of shares. It was his intention to get off the boat at San Francisco and cross the continent by rail. He particularly wanted to see the Grand Canyon of Arizona. And when he found that Myrtle Banks had for years cherished the same desire, it seemed to him so plain a proof that they were twin souls that he decided to offer her his hand and heart without delay.

This Miss Banks had been a fellow-traveller on the boat all the way from Hong-Kong; and day by day William Mulliner had fallen more and more deeply in love with her. So on the last day of the voyage, as they were steaming in at the Golden Gate, he proposed.

I have never been informed of the exact words which he employed, but no doubt they were eloquent. All the Mulliners have been able speakers, and on such an occasion he would, of course, have extended himself. When at length he finished, it seemed to him that the girl’s attitude was distinctly promising. She stood gazing over the rail into the water below in a sort of rapt way. Then she turned.

“Mr. Mulliner,” she said, “I am greatly flattered and honoured by what you have just told me.” These things happened, you will remember, in the days when girls talked like that. “You have paid me the greatest compliment a man can bestow on a woman. And yet——”

William Mulliner’s heart stood still. He did not like that “And yet——”

“Is there another?” he muttered.

“Well, yes. there is. Mr. Franklyn proposed to me this morning. I told him I would think it over.”

There was a silence. William was telling himself that he had been afraid of that bounder Franklyn all along. He might have known, he felt, that Desmond Franklyn would be a menace. The man was one of those lean, keen, hawk-faced, Empire-building sort of chaps you find out East—the kind of fellow who stands on deck chewing his moustache with a far-away look in his eyes, and then, when the girl asks him what he is thinking about, draws a short, quick breath and says he is sorry to be so absent-minded, but a sunset like that always reminds him of the day when he killed the four pirates with his bare hands and saved dear old Tuppy Smithers in the nick of time.

“There is a great glamour about Mr. Franklyn,” said Myrtle Banks. “We women admire men who do things. A girl cannot help but respect a man who once killed two sharks with a Boy Scout pocket-knife.”

“So he says,” growled William.

“He showed me the pocket-knife,” said the girl, simply. “And on another occasion he brought down three lions with three successive shots.”

William Mulliner’s heart was heavy, but he struggled on.

“Very possibly he may have done these things,” he said, “but surely marriage means more than this. I yield to no man in my respect for those who can kill sharks with pocket-knives, but I hold that other qualities are needed by the perfect husband. Personally, if I were a girl, I would go rather for a certain steadiness and stability of character. To illustrate what I mean, did you happen to see me win the Egg-and-Spoon race at the ship’s sports? Now there, it seems to me, in what I might call microcosm, was an exhibition of all the qualities a married man most requires—intense coolness, iron resolution, and a quiet, unassuming courage. The man who under test conditions has carried an egg once and a half times round a deck in a small spoon is a man who can be trusted.”

She seemed to waver, but only for a moment.

“I must think,” she said. “I must think.”

“Certainly,” said William. “You will let me see something of you at the hotel, after we have landed?”

“Of course. And if—I mean to say, whatever happens, I shall always look on you as a dear, dear friend.”

“M’yes,” said William Mulliner.

FOR three days my Uncle William’s stay in San Francisco was as pleasant as could reasonably be expected, considering that Desmond Franklyn was also stopping at his and Miss Banks’s hotel. He contrived to get the girl to himself to quite a satisfactory extent; and they spent many happy hours together in the Golden Gate Park and at the Cliff House, watching the seals basking on the rocks. But on the evening of the third day the blow fell.

“Mr. Mulliner,” said Myrtle Banks. “I want to tell you something.”

“Anything,” breathed William, tenderly, “except that you are going to marry that perisher Franklyn.”

“But that is exactly what I was going to tell you, and I must not let you call him a perisher, for he is a very brave, intrepid man.”

“When did you decide on this rash act?” asked William, dully.

“Scarcely an hour ago. We were talking in the garden, and somehow or other we got on to the subject of rhinoceroses. He then told me how he had once been chased up a tree by a rhinoceros in Africa and escaped by throwing pepper in the brute’s eyes. He most fortunately chanced to be eating his lunch when the animal arrived, and he had a hard-boiled egg and the pepper-pot in his hands. When I heard this story, like Desdemona, I loved him for the dangers he had passed, and he loved me that I did pity them. The wedding is to be in June.”

William Mulliner ground his teeth in a sudden access of jealous rage.

“Personally,” he said, “I consider that the story you have just related reveals this man Franklyn in a very dubious—I might almost say sinister—light. On his own showing, the leading trait in his character appears to be cruelty to animals. The fellow seems totally incapable of meeting a lion or a rhinoceros or any other of our dumb friends without instantly going out of his way to inflict bodily injury on it. The last thing I would wish is to be indelicate, but I cannot refrain from pointing out that, if your union is blessed, your children will probably be the sort of children who kick cats and tie tin cans to dogs’ tails. If you take my advice, you will write the man a little note, saying that you are sorry but you have changed your mind.”

The girl rose in a marked manner.

“I do not require your advice, Mr. Mulliner,” she said, coldly. “And I have not changed my mind.”

Instantly William Mulliner was all contrition. There is a certain stage in the progress of a strong man’s love when he feels like curling up in a ball and making little bleating noises if the object of his affections so much as looks cross-eyed at him; and this stage my Uncle William had reached. He followed her as she paced proudly away through the hotel lobby, and stammered incoherent apologies. But Myrtle Banks was adamant.

“Leave me, Mr. Mulliner,” she said, pointing at the revolving door that led into the street. “You have maligned a better man than yourself, and I wish to have nothing more to do with you. Go!”

William went, as directed. And so great was the confusion of his mind that he got stuck in the revolving door and had gone round in it no fewer than eleven times before the hall-porter came to extricate him.

“I would have removed you from the machinery earlier, sir,” said the hall-porter deferentially, having deposited him safely in the street, “but my bet with my mate in there called for ten laps. I waited till you had completed eleven so that there should be no argument.”

William looked at him dazedly.

“Hall-porter,”he said.

“Sir?”

“Tell me, hall-porter,” said William, “suppose the only girl you had ever loved had gone and got engaged to another, what would you do?”

The hall-porter considered.

“Let me get this right,” he said. “The proposition is, if I have followed you correctly, what would I do supposing the Jane on whom I had always looked as a steady mamma had handed me the old skimmer and told me to take all the air I needed because she had gotten another sweetie?”

“Precisely.”

“Your question is easily answered,” said the hall-porter. “I would go around the corner and get me a nice stiff drink at Mike’s Place.”

“A drink?”

“Yes, sir. A nice stiff one.”

“At—where did you say?”

“Mike’s Place, sir. Just round the corner. You can’t miss it.”

William thanked him and walked away. The man’s words had started a new, and in many ways interesting, train of thought. A drink? And a nice stiff one? There might be something in it.

William Mulliner had never tasted alcohol in his life. He had promised his late mother that he would not do so until he was either twenty-one or forty-one—he could never remember which. He was at present twenty-nine; but, wishing to be on the safe side in case he had got his figures wrong, he had remained a teetotaller. But now, as he walked listlessly along the street towards the corner, it seemed to him that his mother in the special circumstances could not reasonably object if he took a slight snort. He raised his eyes to heaven, as though to ask her if a couple of quick ones might not be permitted; and he fancied that a faint, far-off voice whispered “Go to it!”

And at this moment he found himself standing outside a brightly-lighted saloon.

For an instant he hesitated. Then, as a twinge of anguish in the region of his broken heart reminded him of the necessity for immediate remedies, he pushed open the swing doors and went in.

THE principal feature of the cheerful, brightly-lit room in which he found himself was a long counter, at which were standing a number of the citizenry, each with an elbow on the woodwork and a foot upon the neat brass rail which ran below. Behind the counter appeared the upper section of one of the most benevolent and kindly-looking men that William had ever seen. He had a large, smooth face, and he wore a white coat, and he eyed William, as he advanced, with a sort of reverent joy.

“Is this Mike’s Place?” asked William.

“Yes, sir,” replied the white-coated man.

“Are you Mike?”

“No, sir. But I am his representative, and have full authority to act on his behalf. What can I have the pleasure of doing for you?”

The man’s whole attitude made him seem so like a large-hearted elder brother that William felt no diffidence about confiding in him. He placed an elbow on the counter and a foot on the rail, and spoke with a sob in his voice.

“Suppose the only girl you had ever loved had gone and got engaged to another, what in your view would best meet the case?”

The gentlemanly bar-tender pondered for some moments.

“Well,” he replied at length, “I advance it, you understand, as a purely personal opinion, and I shall not be in the least offended if you decide not to act upon it: but my suggestion—for what it is worth—is that you try a Dynamite Dew-Drop.”

One of the crowd that had gathered sympathetically round shook his head. He was a charming man with a black eye, who had shaved on the preceding Thursday.

“Much better give him a Dreamland Special.”

A second man, in a sweater and a cloth cap, had yet another theory.

“You can’t beat an Undertaker’s Joy.”

They were all so perfectly delightful and appeared to have his interests so unselfishly at heart that William could not bring himself to choose between them. He solved the problem in diplomatic fashion by playing no favourites and ordering all three of the beverages recommended.

The effect was instantaneous and gratifying. As he drained the first glass, it seemed to him that a torchlight procession, of whose existence he had hitherto not been aware, had begun to march down his throat and explore the recesses of his stomach. The second glass, though slightly too heavily charged with molten lava, was extremely palatable. It helped the torchlight procession along by adding to it a brass band of singular power and sweetness of tone. And with the third somebody began to touch off fireworks inside his head.

William felt better—not only spiritually but physically. He seemed to himself to be a bigger, finer man, and the loss of Myrtle Banks had somehow in a flash lost nearly all its importance. After all, as he said to the man with the black eye, Myrtle Banks wasn’t everybody.

“Now what do you recommend?” he asked the bar-tender, having turned the last glass upside down.

The bar-tender mused again, one forefinger thoughtfully pressed against the side of his face.

“Well, I’ll tell you,” he said. “When my brother Elmer lost his girl, he drank straight rye. Yes, sir. That’s what he drank—straight rye. ‘I’ve lost my girl,’ he said, ‘and I’m going to drink straight rye.’ That’s what he said. Yes, sir. Straight rye.”

“And was your brother Elmer,” asked William, anxiously, “a man whose example in your opinion should be followed? Was he a man you could trust?”

“He owned the biggest duck-farm in the southern half of Illinois.”

“That settles it,”said William. “What was good enough for a duck who owned half Illinois is good enough for me. Oblige me by asking these gentlemen what they will have, and start pouring.”

The bar-tender obeyed, and William, having tried a pint or two of the strange liquid just to see if he liked it, found that he did, and ordered some. He then began to move about among his new friends, patting one on the shoulder, slapping another affably on the back, and asking a third what his Christian name was.

“I want you all,” he said, climbing on to the counter so that his voice should carry better, “to come and stay with me in England. Never in my life have I met men whose faces I liked so much. More like brothers than anything is the way I regard you. So just you pack up a few things and come along and put up at my little place for as long as you can manage. You particularly, my dear old chap,” he added, beaming at the man in the sweater.

“Thanks,” said the man with the sweater.

“What did you say?” said William.

“I said, ‘Thanks.’ ”

William slowly removed his coat and rolled up his shirt-sleeves.

“I call you gentlemen to witness,” he said, quietly, “that I have been grossly insulted by this gentleman who has just grossly insulted me. I am not a quarrelsome man, but if anybody wants a row they can have it. And when it comes to being cursed and sworn at by an ugly bounder in a sweater and a cloth cap, it is time to take steps.”

And with these spirited words William Mulliner sprang from the counter, grasped the other by the throat, and bit him sharply on the right ear. There was a confused interval, during which somebody attached himself to the collar of William’s waistcoat and the seat of William’s trousers, and then a sense of swift movement and rush of cool air.

William discovered that he was seated on the pavement outside the saloon. A hand emerged from the swing door and threw his hat out. And he was alone with the night and his meditations.

These were, as you may suppose, of a singularly bitter nature. Sorrow and disillusionment racked William Mulliner like a physical pain. That his friends inside there, in spite of the fact that he had been all sweetness and light and had not done a thing to them, should have thrown him out into the hard street was the saddest thing he had ever heard of; and for some minutes he sat there, weeping silently.

Presently he heaved himself to his feet: and, placing one foot with infinite delicacy in front of the other, and then drawing the other one up and placing it with infinite delicacy in front of that, he began to walk back to his hotel.

At the corner he paused. There were some railings on his right. He clung to them and rested awhile.

The railings to which William Mulliner had attached himself belonged to a brownstone house of the kind that seems destined from the first moment of its building to receive guests, both resident and transient, at a moderate weekly rental. It was, in fact, as he would have discovered had he been clear-sighted enough to read the card over the door, Mrs. Beulah O’Brien’s Theatrical Boarding-House (“A Home From Home—No Cheques Cashed—This Means You”).

But William was not in the best of shape for reading cards. A sort of mist had obscured the world, and he was finding it difficult to keep his eyes open. And presently, his chin wedged into the railings, he fell into a dreamless sleep.

HE was awakened by light flashing in his eyes; and, opening them, saw that a window opposite where he was standing had become brightly illuminated. His slumbers had cleared his vision; and he was able to observe that the room into which he was looking was a dining-room. The long table was set for the evening meal; and to William, as he gazed, the sight of that cosy apartment, with the gaslight falling on the knives and forks and spoons, seemed the most pathetic and poignant that he had ever beheld.

A mood of the most extreme sentimentality now had him in its grip. The thought that he would never own a little home like that racked him from stem to stern with an almost unbearable torment. What, argued William, clinging to the railings and crying weakly, could compare, when you came right down to it, with a little home? A man with a little home is all right, whereas a man without a little home is just a bit of flotsam on the ocean of life. If Myrtle Banks had only consented to marry him, he would have had a little home. But she had refused to marry him, so he would never have a little home. What Myrtle Banks wanted, felt William, was a good swift clout on the side of the head.

The thought pleased him. He was feeling physically perfect again now, and seemed to have shaken off completely the slight indisposition from which he had been suffering. His legs had lost their tendency to act independently of the rest of his body. His head felt clearer, and he had a sense of overwhelming strength. If ever, in short, there was a moment when he could administer that clout on the side of the head to Myrtle Banks as it should be administered, that moment was now.

He was on the point of moving off to find her and teach her what it meant to stop a man like himself from having a little home, when someone entered the room into which he was looking, and he paused to make further inspection.

The new arrival was a coloured maid-servant. She staggered to the head of the table beneath the weight of a large tureen containing, so William suspected, hash. A moment later a stout woman with bright golden hair came in and sat down opposite the tureen.

The instinct to watch other people eat is one of the most deeply implanted in the human bosom, and William lingered, intent. There was, he told himself, no need to hurry. He knew which was Myrtle’s room in the hotel. It was just across the corridor from his own. He could pop in any time during the night and give her that clout. Meanwhile, he wanted to watch these people eat hash.

And then the door opened again, and there filed into the room a little procession. And William, clutching the railings, watched it with bulging eyes.

The procession was headed by an elderly man in a check suit with a carnation in his buttonhole. He was about three feet six in height, though the military jauntiness with which he carried himself made him seem fully three feet seven. He was followed by a younger man who wore spectacles and whose height was perhaps three feet four. And behind these two came, in single file, six others, scaling down by degrees until, bringing up the rear of the procession, there entered a rather stout man in tweeds and bedroom slippers who could not have measured more than two feet eight.

They took their places at the table. Hash was distributed to all. And the man in tweeds, having inspected his plate with obvious relish, removed his slippers and, picking up knife and fork with his toes, fell to with a keen appetite.

William Mulliner uttered a soft moan, and tottered away.

It was a black moment for mv Uncle William. Only an instant before he had been congratulating himself on having shaken off the effects of his first indulgence in alcohol after an abstinence of twenty-nine years; but now he perceived that he was still intoxicated.

Intoxicated? The word did not express it by a mile. He was oiled, boiled, fried, plastered, whiffled, sozzled, and blotto. Only by the exercise of the most consummate caution and address could he hope to get back to his hotel and reach his bedroom without causing an open scandal.

Of course, if his walk that night had taken him a few yards farther down the street than the door of Mike’s Place, he would have seen that there was a very simple explanation of the spectacle which he had just witnessed. A walk so extended would have brought him to the San Francisco Palace of Varieties, outside which large posters proclaimed the exclusive engagement for two weeks of

MURPHY’S MIDGETS.

BIGGER AND BETTER THAN EVER.

But of the existence of these posters he was not aware; and it is not too much to say that the iron entered into William Mulliner’s soul.

That his legs should have become temporarily unscrewed at the joints was a phenomenon which he had been able to bear with fortitude. That his head should be feeling as if a good many bees had decided to use it as a hive was unpleasant, but not unbearably so. But that his brain should have gone off its castors and be causing him to see visions was the end of all things.

William had always prided himself on the keenness of his mental powers. All through the long voyage on the ship, when Desmond Franklyn had related anecdotes illustrative of his prowess as a man of action, William Mulliner had always consoled himself by feeling that in the matter of brain he could give Franklyn three bisques and a beating any time he chose to start. And now, it seemed, he had lost even this advantage over his rival. For Franklyn, dull-witted clod though he might be, was not such an absolute minus quantity that he would imagine he had seen a man of two feet eight cutting up hash with his toes. That hideous depth of mental decay had been reserved for William Mulliner.

Moodily he made his way back to his hotel. In a corner of the Palm Room he saw Myrtle Banks deep in conversation with Franklyn, but all desire to give her a clout on the side of the head had now left him. With his chin sunk on his breast, he entered the elevator and was carried up to his room.

Here, as rapidly as his quivering fingers would permit, he undressed; and, climbing into the bed as it came round for the second time, lay for a space with wide-open eyes. He had been too shaken to switch his light off, and the rays of the lamp shone on the handsome ceiling which undulated above him. He gave himself up to thought once more.

No doubt, he felt, thinking it over now, his mother had had some very urgent reason for withholding him from alcoholic drink. She must have known of some family secret, sedulously guarded from his infant ears—some dark tale of a fatal Mulliner taint. “William must never learn of this!” she had probably said when they told her the old legend of how every Mulliner for centuries back had died a maniac, victim at last to the fatal fluid. And to-night, despite her gentle care, he had found out for himself.

He saw now that this derangement of his eyesight was only the first step in the gradual dissolution which was the Mulliner Curse. Soon his sense of hearing would go, then his sense of touch.

He sat up in bed. It seemed to him that, as he gazed at the ceiling, a considerable section of it had parted from the parent body and fallen with a crash to the floor.

WILLIAM MULLINER stared dumbly. He knew, of course, that it was an illusion. But what a perfect illusion! If he had not had the special knowledge which he possessed, he would have stated without fear of contradiction that there was a gap six feet wide above him and a mass of dust and plaster on the carpet below.

And even as his eyes deceived him, so did his ears. He seemed to be conscious of a babel of screams and shouts. The corridor, he could have sworn, was full of flying feet. The world appeared to be all bangs and crashes and thuds. A cold fear gripped at William’s heart. His sense of hearing was playing tricks with him already.

His whole being recoiled from making the final experiment, but he forced himself out of bed. He reached a finger towards the nearest heap of plaster and drew it back with a groan. Yes, it was as he feared, his sense of touch had gone wrong too. That heap of plaster, though purely a figment of his disordered brain, had felt solid.

So there it was. One little moderately festive evening at Mike’s Place, and the Curse of the Mulliners had got him. Within an hour of absorbing the first drink of his life, it had deprived him of his sight, his hearing, and his sense of touch. Quick service, felt William Mulliner.

As he climbed back into bed, it appeared to him that two of the walls fell out. He shut his eyes, and presently sleep, which has been well called Tired Nature’s Sweet Restorer, brought oblivion. His last waking thought was that he imagined he had heard another wall go.

WILLIAM MULLINER was a sound sleeper, and it was many hours before consciousness returned to him. When he awoke, he looked about him in astonishment. The haunting horror of the night had passed; and now, though conscious of a rather severe headache, he knew that he was seeing things as they were.

And yet it seemed odd to think that what he beheld was not the remains of some nightmare. Not only was the world slightly yellow and a bit blurred about the edges, but it had changed in its very essentials overnight. Where eight hours before there had been a wall, only an open space appeared, with bright sunlight streaming through it. The ceiling was on the floor, and almost the only thing remaining of what had been an expensive bedroom in a first-class hotel was the bed. Very strange, he thought, and very irregular.

A voice broke in upon his meditations.

“Why, Mr. Mulliner!”

William turned, and being, like all the Mulliners, the soul of modesty, dived abruptly beneath the bed-clothes. For the voice was the voice of Myrtle Banks. And she was in his room!

“Mr. Mulliner!”

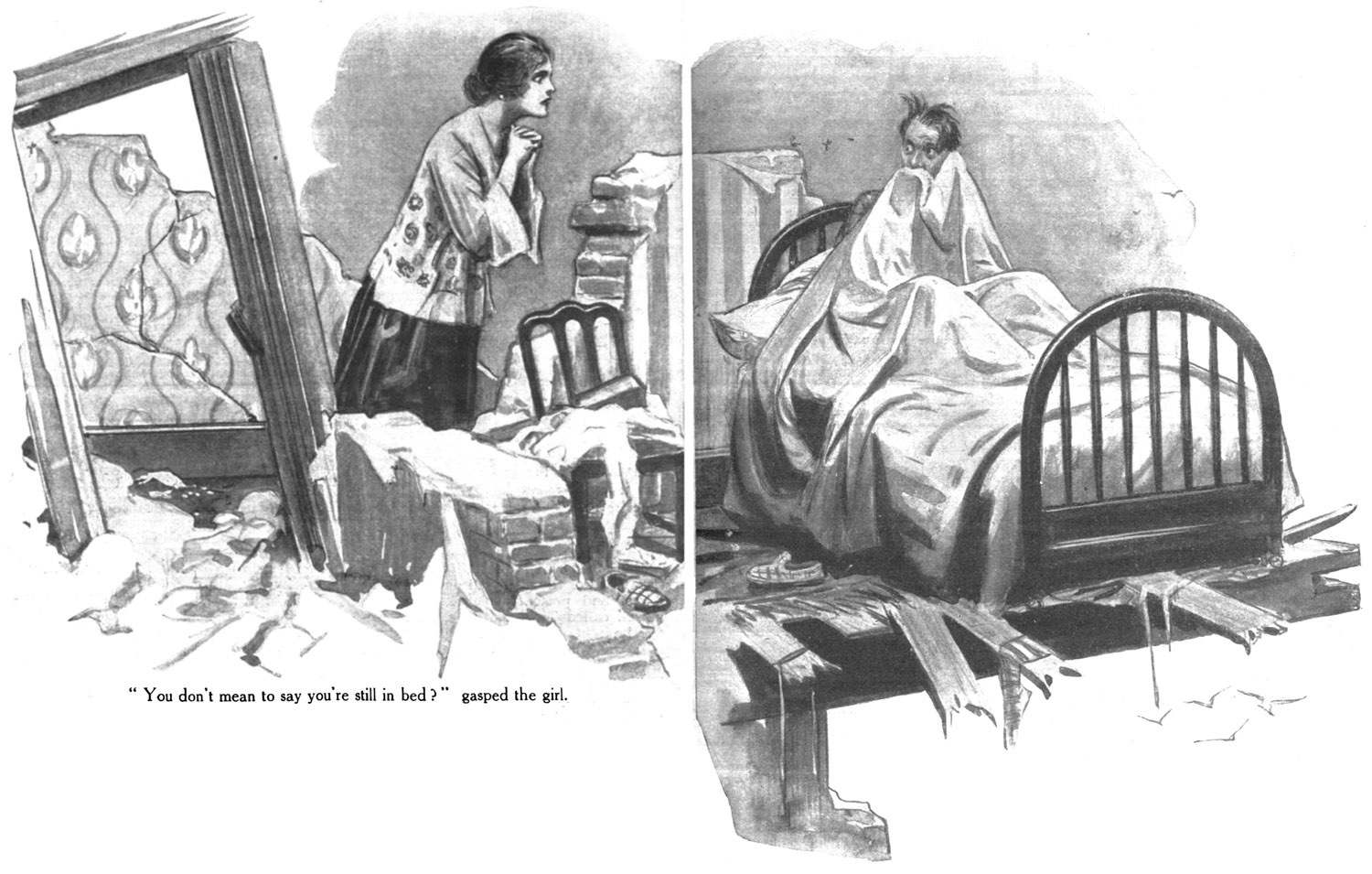

William poked his head out cautiously. And then he perceived that the proprieties had not been outraged as he had imagined. Miss Banks was not in his room, but in the corridor. The intervening wall had disappeared. Shaken, but relieved, he sat up in bed, the sheet drawn round his shoulders.

“You don’t mean to say you’re still in bed?” gasped the girl.

“Why, is it awfully late?” said William.

“Did you actually stay up here all through it?”

“Through what?”

“The earthquake.”

“What earthquake?”

“The earthquake last night.”

“Oh, that earthquake?” said William, carelessly. “I did notice some sort of an earthquake. I remember seeing the ceiling come down and saying to myself, ‘I shouldn’t wonder if that wasn’t an earthquake.’ And then the walls fell out, and I said, ‘Yes, I believe it is an earthquake.’ And then I turned over and went to sleep.”

Myrtle Banks was staring at him with eyes that reminded him partly of twin stars and partly of a snail’s.

“You must be the bravest man in the world!”

William gave a curt laugh.

“Oh, well,” he said, “I may not spend my whole life persecuting unfortunate sharks with pocket-knives, but I find I generally manage to keep my head fairly well in a crisis. We Mulliners are like that. We do not say much, but we have the right stuff in us.”

He clutched his head. A sharp spasm had reminded him how much of the right stuff he had in him at that moment.

“My hero!” breathed the girl, almost inaudibly.

“And how is your fiancé this bright, sunny morning?” asked William, nonchalantly. It was torture to refer to the man, but he must show her that a Mulliner knew how to take his medicine.

She gave a little shudder.

“I have no fiancé,” she said.

“But I thought you told me you and Franklyn——”

“I am no longer engaged to Mr. Franklyn. Last night, when the earthquake started, I cried to him to help me; and he, with a hasty ‘Some other time!’ over his shoulder, disappeared into the open like something shot out of a gun. I never saw a man run so fast. This morning I broke off the engagement.” She uttered a scornful laugh. “Sharks and pocket-knives! I don’t believe he ever killed a shark in his life.”

“And even if he did,” said William, “what of it? I mean to say, how infrequently in married life must the necessity for killing sharks with pocket-knives arise! What a husband needs is not some purely adventitious gift like that—a parlour trick, you might almost call it—but a steady character, a warm and generous disposition, and a loving heart.”

“How true!” she murmured, dreamily.

“Myrtle,” said William, “I would be a husband like that. The steady character, the warm and generous disposition, and the loving heart to which I have alluded are at your disposal. Will you accept them?”

“I will,” said Myrtle Banks.

AND that (concluded Mr. Mulliner) is the story of my Uncle William’s romance. And you will readily understand, having heard it, how his eldest son, my cousin, J. S. F. E. Mulliner, got his name.

“J. S. F. E.?” I said.

“John San Francisco Earthquake Mulliner,” explained my friend.

“There never was a San Francisco earthquake,” said the Californian. “Only a fire.”

(Next month: “Those in Peril on the Tee.”)

Compare the US magazine version of the story, “It Was Only a Fire” from Liberty magazine, April 9, 1927, which is slightly abridged, but correctly puts the San Francisco calamity in “nineteen-six” rather than 1907 as in this version.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums