Vanity Fair, October 1917

A Cloud-burst on the Rialto

Broadway Is Flooded by a Torrent of New Plays

By P. G. WODEHOUSE

THE dam has busted! As if somebody had touched a spring, the theatrical season of 1917 has broken out all over the place at the same time. It is like the Prussian Guard charging in mass formation in an Evening Telegram headline. Or a cloud-burst, or something. In previous seasons one was always allowed a little time to make one’s preparations. About the middle of August a farce would pop up, timid and solitary, like the first snowdrop, and we would look at the little fellow with a kindly interest, feeling that it was a harbinger of better things. Then a drama would sprout, and a little later, strolling down Broadway, we would see that a comedy and a couple of musical shows had blossomed in the night; and then we would say to ourselves “I do believe the new theatrical season must be nearly here.”

But this year everything has started happening all at once, and to be a dramatic critic is like being one of those Coney Island Senegambians who—doubtless from the best of motives—put their head through a hole in a sheet of canvas and have baseballs thrown at them. You can’t dodge the things. If you duck to avoid a new farce, you bump into a symbolic tragedy; if you leap nimbly aside to get out of the way of a revue, a simple, tender study in mother love catches you in the small of the back. The only thing to do is to set your teeth and face the deluge like a man.

AND, talking of deluges, the play of that name at the Hudson Theatre, adapted from the Swedish, has finally decided me to change my name to Hendrik Bjwodehouse and gather in a little easy money. You have to hand it to the Swedes, for there is no gainsaying that these squareheads get away with an awful lot. Here is the author of “The Deluge,” for instance, purely on the strength of having been born in Stockholm, getting three-column reviews in the daily papers, where our native dramatists are lucky if they are given a couple of paragraphs; and being credited with “passionate comments upon the pettiness of life and the immensity of death” and “strange Scandinavian laughter” and all sorts of succulent things like that.

And what is his play about? I’m glad you asked me that, dearie, I’m glad you asked me that, for it gives me an opportunity to tell you. The play is about a number of people gathered together in a saloon, who imagine that the flood is about to sweep them out of existence and that there is no possible escape for them. Now, statistics show that every male adult in this country has written at least one play or story in his time; and of these plays and stories a little over 73.89 have as their theme this very situation. It is usually the plot one starts one’s literary career with. It is a literary pipe-opener. When you have written it, you say to yourself, “Well, that’s that. Now I’ll begin on something worth while.”

I wrote mine about eight years ago: but, when I tried to market it, did editors say that I had “brought together into one room all the passion, the pain, the mystery, the weakness and strength, all the desire and futility of human nature”? No. They said that, owing to pressure of space, they were unable to avail themselves of the enclosed contribution, for the offer of which they were extremely obliged. And all because I had omitted to insert a note claiming that it was adapted from the Swedish. This sort of thing makes one feel like Sinned-Against Samuel in the Journal.

BEFORE the season began, there was much discussion as to how America’s entry into the war would affect the theatre, as regarded the type of play likely to be popular. It would seem that the fundamental law of the stage, that the public likes to laugh, still holds good: for the outstanding successes of August are farces. It is true that Selwyns’ drama, “Daybreak,” is advertised as selling seats ten weeks ahead; but that merely offers additional evidence that the public likes to laugh.

The two biggest hits at present recorded on the score-sheet are “The Very Idea” at the Astor and “Business before Pleasure” at the Eltinge. There is nothing sensational about the success of the latter, in which Montague Glass and Jules Eckert Goodman take Potash and Perlmutter into the movie-business: for it was one of the few plays ever submitted to a manager which a mere reading of the script showed to be cast-iron. If Montague Glass is not America’s leading humorist, he is certainly in the first two, and in “Business before Pleasure” he is at the very top of his form. There has probably never been a play at which the audience laughed so continuously. It is just a gale of mirth from the rise of the curtain. There seems no reason why, providing Barney Bernard and Alexander Carr keep their health, these Potash and Perlmutter plays should not become an annual institution like the Follies. Let us hope they will.

THE backers of “The Very Idea” must have entered the theatre on the opening night with considerably more nervousness than did Mr. A. H. Woods at the opening of “Business before Pleasure”; for nobody could have predicted that the play would make such a sensational hit. In the first place, it was written by a new author, William le Baron: in the second place it dealt with the always dangerous theme of Eugenics. Most theatrical people distrust Eugenics as much as they do yacht-scenes, which have hoo-dooed numberless productions.

But it was soon made plain that this time, owing to the author’s humor and good taste and the excellent acting of Ernest Truex, Richard Bennett, and the rest of a fine cast, Eugenics were a success. There is no one who approaches Ernest Truex in the sort of part which calls for a number thirteen collar and shoes that are number three. He is the best small husband on either side of the Atlantic. But, good as the acting is, the play is the thing. Mr. le Baron has written the best farce, not excepting “Fair and Warmer,” that has come this way in a long time.

The season opened with another farce, “Mary’s Ankle,” at the Bijou. It seems to have settled down into a good, steady success,—adequate without being startling. It suffers by comparison with its two rivals, but it is full of funny situations, notably the pawning of the landlady’s parrot by the doctor with whom the bird has been left to be treated for adenoids. Irene Fenwick is charming as the owner of the injured ankle. Barnett Parker, who was so good in “Hobson’s Choice,” is again funny, this time in the rôle of a steward.

“Friend Martha” I did not see. It just popped in and popped out again. But one’s luck never lasts, and I saw both “The Inner Man” and “Daybreak. ” “Daybreak” deals with the problem of a woman married to a drunkard, who does not wish her child to come in contact with its father, so conceals the fact of its existence and keeps it somewhere off-stage,—a situation which has been handled with great power on somewhat different lines by the author of that poignant ballad “The dog disliked the baby, so we gave the child away.”

“Daybreak” is chiefly interesting in that it shows us what surely must be the final word in drinkers. Arnold Daly quaffed a bit in “The Very Minute,” and Lord Dunsany, writing of a certain sailorman, complains that “many people think that poor old Bill is drunk just because he can’t move”: but neither of these doughty alcoholics can compete with Arthur Frome, in “Daybreak,” who not only gets very comfortably below the surface before breakfast but gathers speed during the day till, round about the edge of the afternoon, he is massacring polo ponies and newsboys.

SPEAKING of unpleasant citizens, go to “The Inner Man” and take a look at “Devil Bolger.” He is the more amazing, in that there is no evidence that he does not do it all on cocoa. This play would have been the better for a touch of that “strange Scandinavian laughter” stuff. In other words, it is killed by the lightning reformation of its villain-hero in the last act. An ironical treatment of social reform would have been more satisfying. Devil Dick should never have repented and become reconciled to his wife and child. In these days of moving-picture soul-dramas, what the public is crying out for is a play where the tough egg spurns his wife and kicks his child at the final curtain. Mr. Abraham Schomer had a great chance, but he threw it away.

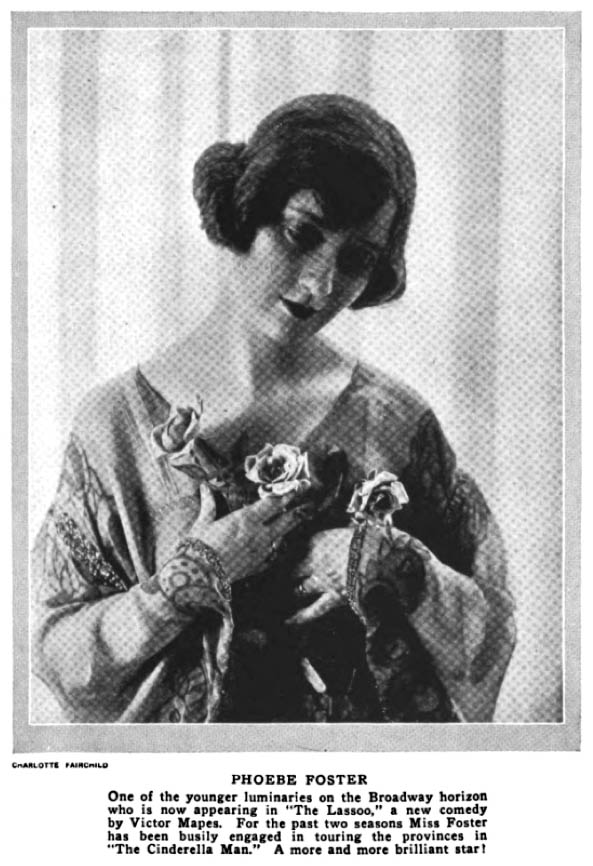

“The Boomerang,” by Winchell Smith and Victor Mapes was a good play. “The Lassoo,” by Victor Mapes, is only half a good play. Thus do we see a logic in everything. Every season the peril of writing a play without Winchell Smith as a collaborator becomes more apparent.

THE last of the first batch of this season’s plays is “The Eyes of Youth,” which brings the always wonderful Marjorie Rambeau to New York as a star. Written by Max Marcin and Charles Guernon, and dealing with the visions of the future seen by a girl who looks into a crystal brought to her by a Yogi, in which rôle Macey Harlem established herself as our leading yoger, it seemed to hand the critics something of a jolt. They sniffed at it and turned it over with their paws suspiciously. It puzzled them. The nearest one of them could come to a definition of it was by saying that it was a blend of “On Trial,” “Peter Ibbetson,” “Everywoman,” “Experience,” and “Bunker Bean”! What none of them seemed to realize was that it is a play which will draw women like a magnet, and that way success lies. Stephen Leacock in “Behind the Beyond” sums up very well what is going to happen to “The Eyes of Youth.” He describes a first-night audience discussing the new problem-play: and some say that its symbolism is too intense, and others that its intensity it too symbolical. But all the while there is a man in a circus waistcoat in the box-office checking up the seat-sale; and he smiles contentedly, for he knows the play is all right.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums