Vanity Fair, November 1915

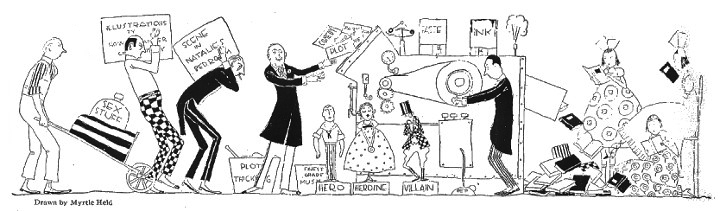

A VISIT TO THE R. W. CHAMBERS FICTION PLANT

By J. Walker Williams

“ TELL us,” we said, “how on earth you do it. Wherever we look, we seem to see nothing but your temptation stories. We have to-day reached the end of your latest serial in America’s greatest magazine, and, just as we were mopping our forehead and saying, ‘Well, that’s that!’ we caught sight of an editorial note saying that your new one would begin next month. How do you manage it?”

“System,” replied Mr. Robert W. Chambers. “Nothing but system. Perhaps you would like to stroll through the plant?”

The Chambers Fiction plant is, with the exception of Mr. Henry Ford’s eruption of automobiles, the largest single industry in the country, and is conducted on much the same principles. Everybody knows by now how a Ford car is put together. Workmen have been toiling day and night, preparing the various standardized parts, so that, when an order comes in, all they have to do is to put them together. Mike has a barn full of differential gears, George a few acres of carburetors, Ike more cylinders than he knows what to do with, Bill’s long suit is wheels, and Percy knows just where to dig up a chassis or two when required. The consequence is that, directly you come in with your order, Mike, George, Ike, Bill, and Percy pick up the nearest thing in sight, rush to Clarence who has charge of the string and mucilage, and the thing is put together while you wait.

Very much the same secret is at the root of Mr. Chambers’ great success in literature. He has learned the value of standardization. He has the modern touch. He knows the importance of speed. Competition is too keen to permit of delay. It was the necessity of putting on just that extra turn of speed which led Mr. Chambers to hit on the real secret of his method,—the standardization of parts.

There is one vast section of the factory given over entirely to the manufacture of love-scenes. Skilled workmen labor incessantly under the personal direction of the inventor, turning out detached chapters on the formula patented by him. In another part of the building expert nature-fakers are preparing descriptions of scenery and insect life. A whole wing of the works is given over to a corps of assistants whose sole duty it is to think up new names for heroines. Heroes are attended to elsewhere, and there is a small comedy room in the basement.

It was my privilege to be present when Mr. Hearst called up Mr. Chambers on the telephone for another novel, to be delivered on the following morning, and I have seldom seen such an exhibition of intense organized activity. From all corners of the building workmen came rushing, one with a chunk of dialogue, another with specimen names for the heroine, a third wheeling a carefully-sealed carboy of sex stuff to be used for flavoring. There was no blundering, no confusion. The man with the chapter in Natalie’s bedroom did not trip over the man with the scene where the erring husband drinks himself to death. The nature-fakers scuttled in and out, doing their little bit. Before one could believe it, the machine was complete, and there only remained the testing of it on the staff of resident school-girls which is one of the features of the Chambers Plant. Long before the specified time the thing was on its way to the editor’s office, complete in every detail and guaranteed similar in every respect to all previous productions bearing the firm’s name.

Mr. Chambers received my congratulations modestly.

“A mere nothing,” he said. “In this particular case the order was given in plenty of time, and there was no real hurry. You should see us one of these days when we are really pushed. There is no mystery about my process. The formula is everything. I have been fortunate enough to hit on one which is, for practical purposes, perfect, and the rest is easy. Long experience has taught me the exact degree of Howard Chandler Christyhood necessary for the composition of a heroine, and I know precisely how long and—still more important—how broad a love scene must be to make a stenographer cut down her chewing-gum expenditure in order to have the fifteen cents for reading me serially. I always use the best wood in the manufacture of my heroes.”

“Wonderful, wonderful!” I said, as I left.

Notes:

Chambers’s novel Athalie was serialized in Cosmopolitan, concluding in the August 1915 issue; the serialization of The Girl Philippa began in the September 1915 issue. The monthly cover price was indeed fifteen cents.

Howard Chandler Christy (1873–1952) was one of America’s best-known magazine artists; his idealized “Christy Girl” was almost as well known as Charles Dana Gibson’s “Gibson Girl.” Christy’s illustrations for a Jack London serial were appearing in Cosmopolitan at this period.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums