Vanity Fair, February 1917

AN APPRECIATION OF VAUDEVILLE

A Kind Word for Nora Bayes, and for the Two-a-Day

By P. G. Wodehouse

IT is a remarkable proof of my sagacity and good judgment that, while I have never experienced the slightest desire to go on the legitimate stage, it was my earliest ambition to become a vaudeville artist.

Even at the tender age of twelve, vaudeville appealed to me, and, though still a child, I could perceive that to succeed in vaudeville called for many of the nobler qualities which any thinking man would be glad to possess. I gave up my boyhood dreams reluctantly, but my admiration remained, and I have never since been able to dismiss the vaudevillian with a contemptuous gesture, as many people do, on the ground that he is a member of an ignoble profession and not fit to be classed with the World’s Uplifters.

I disagree absolutely with this theory. When I hear that some eminent two-a-day performer receives a salary greater than that of President Wilson, my only feeling is that he probably deserves it. For, to succeed in vaudeville, one has to have special gifts. You cannot achieve success by pull or by mere amiability of disposition. You cannot go into vaudeville, as you can on the legitimate stage, to amuse yourself or to tide over the lean period in which the old dad is deciding whether or not to resume your allowance. In no other walk of life is it so exclusively up to the individual.

TAKE any other profession, and compare it with the two-a-day. Finance, shall we say? In comparison with our best vaudeville artists, financiers have a disgracefully soft time of it. All John D. Rockefeller has to do when he wants another million is to stop at a nickel-in-the-slot ’phone on his way to the links and tell the boys down in Wall Street to make it for him. Then he hangs up the receiver, feels in the machine to see if by any miracle the telephone company has returned his nickel, and strolls off to the first tee humming a gay melody.

Or the Army? What does a General do? He sits in a cosy room and orders the army to get a move on itself. After that he lights a cigar and gets out the solitaire deck.

Or Statesmanship? What have statesmen to do? Nothing. They do not even have to vote for themselves. No, there is no doubt about it. The supreme test of man or woman is whether he or she can succeed in vaudeville. It was not because I considered authorship a grander pursuit than singing on the Orpheum circuit that I abandoned my boyhood’s dreams. It was because I knew that any chump can make a living as an author—and, if you don’t believe it, just look at some of our authors,—whereas, to be a vaudeville star, you require vim, pep, espieglerie, a good singing voice, and a species of indefinable je-ne-sais-quoi,—none of which qualities I seem to possess.

IT is the lonesomeness of the job that makes vaudeville so hard. You have no supports. You remember how you used to feel when they dragged you down to the drawing-room as a child and made you recite that little thing about the Hesperus? Well, that is how vaudeville performers feel all the time. The heroine of a musical comedy has the support and approval in whatever she does of a chorus of seventy-five. They follow her about. They bound in the background during her songs. They open parasols, and wear Lucile dresses. They make her feel that they, at least, are strong for her.

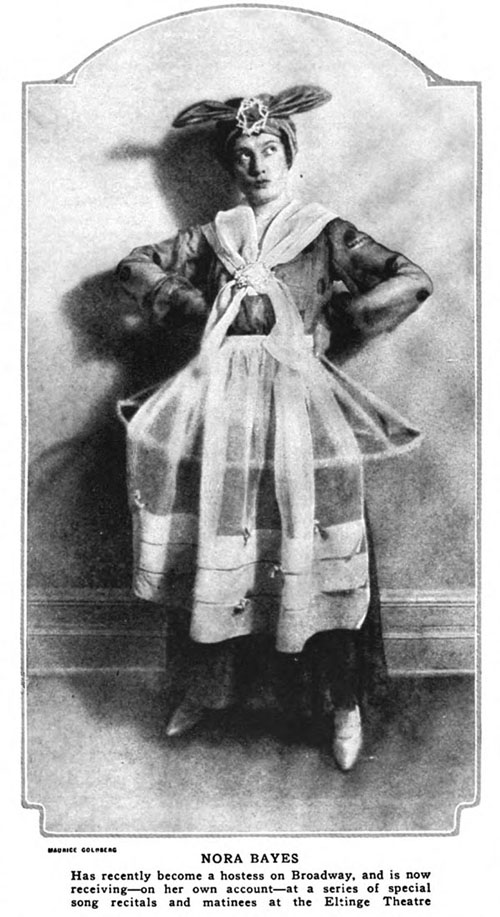

How very different is the case of Miss Nora Bayes, who has just become her own vaudeville manager, and captured the multitudes on Broadway. She starts her act on an empty stage, all alone in a hard world. If she is to receive any friendly support, it must come from the audience, and to get it from the audience—that aggregation of sullen, glowering, frozen-faced, set-jawed individuals—she has got to show them something which will galvanize them into life with a jerk: for a vaudeville artist finds that her allotted time on the stage is short, and if she is going to get an effect she must get it at once, without planning or scheming for it.

It is a mystery to me why so many people overlook this fact. People who feel sorry for David when he sang before Saul and found him such a poor audience, will tell you that they think vaudeville artists earn their money easily.

Lonesomeness is only one of the drawbacks to the vaudevillian’s life. The fierceness of the competition is another. There is something miraculous in the ability of the denizens of the vaudeville world to imitate each other. Let us suppose that, after much tense thought and studious practise, you have perfected some unusual act. Let us say that you burst on an astonished world as Dare-Devil Desmond, the only man who can ride a motor-bicycle head-downwards across the ceiling. Do not imagine for an instant that you will be allowed to enjoy the fruits of your enterprise unchallenged. In about two weeks rivals, doing the same act just as well, will appear simultaneously in every state of the Union, and by the end of the season your act will be stale, and in order to get bookings you will have to invent something with a little more pep in it.

THIS brings about another result which helps to add to the toughness of life for the vaudeville artist. There are no limits to the amount which the public demands for its money. As regards the legitimate stage, this is not the case. If John Drew wears a decent suit of clothes and goes through his lines satisfactorily, his audience is satisfied. His public does not expect him to fill out with a bit of trick juggling or a ballroom specialty dance. But if he were on the vaudeville stage, it would be quite another matter. Take, for example, the case of the vaudeville juggler. To the ordinary man who cannot carry a tea-cup across a room without spilling the contents and nearly dropping it twice, it would seem that any one who can balance a chair, two vases, three billiard-balls, a cue, and a female assistant on the tip of his nose is doing enough to earn his salary and should not be called upon to elaborate his performance. But in vaudeville a trifling feat like this is only the beginning. Unless he wants to spend his life sandwiched in between the films at some four-a-day house, the vaudeville juggler must not loaf on his job. While doing the above-mentioned balancing act, the least the public will allow him to supplement it with is a bit of rapid work with half a dozen plates with his left hand, while with his right he throws up and catches in brisk succession a few gross of india-rubber balls. And even then the audience is inclined to ask itself if the fellow can’t find anything to do with his feet. In addition to all this, the poor man is expected to be a finished comedian and keep up a rapid-fire of humorous gags all through his act. I knew an excellent violinist who could only secure bookings in vaudeville by playing with the instrument behind his back. At that, he had to sing a couple of comic songs as well. And unthinking people grudge these men their money!

I HAVE often wondered how vaudeville performers first get the idea of becoming vaudeville performers. My own case, of course, was rather different. I just wanted to sing. And everybody wants to sing. The people who don’t want them to, are the other people. But how does a man who dives from a hole in the roof into a small tank first get the impulse? One pictures such a performer studying peacefully for the Church, without a thought of any other walk in life, when suddenly, one evening, as he sits among his theological books, a thought flashes across his mind. “This is all very well,” whispers some inward voice, “but what Nature really intended you to do was to dive from a roof into a tank. Do not stifle your individuality.” So he throws away his books and goes off to see Pat Casey or somebody else about bookings.

But where and how does he practise? There was a man at Madison Square Garden seven or eight years ago who used to stand on one of the girders which support the roof and dive head-foremost onto a sloping chute. Down this he would slide, on his stomach, finally turning a somersault in mid-air and alighting on his feet with an expression of modest pride, as who should say, “You thought I was a boob when I started my dive—didn’t you, now?” The mind pauses baffled at the contemplation of the steps that led up to that perfected act. The early rehearsals must have been worth seeing.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums