Vanity Fair, January 1915

COMMUTING AT THE THEATRE

A Playgoer’s Plea for Dramatic Trip Tickets

By Pelham Grenville

IT seems to be universally admitted that the past season—like all other previous seasons—has been the worst in the history of the New York stage, and earnest enquirers are trying to ascertain the reason.

One cause assigned for the lean times is that the plays have been bad. The absurdity of this hypothesis may be proved by a glance at the theatrical advertisements.

These all show that every piece produced is “a striking, smashing, stupendous, genuine, or indubitable, hit.” Each play is what the public has been waiting twenty years to see; and the only trouble is that the public, having waited so long, seems to feel that it may as well go on waiting a little longer. And, while it is doing so, the management finds that it forgot to insert three words in its advertisement. It proceeds to repair the omission. “The Last Week” are the words in question. They are possibly the saddest words that pen can form.

I have given much thought to this subject, and I have been rewarded with a solution, so simple that it seems strange that it has never been put into practice. Like all great ideas, it was waiting, ready to be picked up by anyone.

The railroads have already tried the scheme with success and there is no reason why the theatres should not resort to the same expedient.

I refer to the mileage system.

ALL railroads recognize that the purest of pleasures may cloy, so, instead of forcing their patrons every time to travel the entire distance of a journey or not travel at all, they say, in effect, “See here, old man, you like traveling and I like having you travel, but it does get a bit tedious after a while, doesn’t it? Well, I’ll tell you what we’ll do: you pay me so much, and then you can come and travel in instalments whenever you feel inclined, till you’ve used up all of your little white trip ticket-book.”

And so with the theatres!

What is really the trouble with the New York drama is that it has reached such a stage of “striking, stupendous, smashing, genuine, and indubitable” hittishness, that the ordinary man is not equal to a sustained orgy of it. After about half an hour of it the pleasure becomes too delirious, and he wishes that he might be elsewhere. But he has paid his two dollars, and the instinct of the commercial-minded citizen compels him to sit the thing out and not let the management get ahead of him by seventy-five cents of his hard-earned money. The result is that he gets surfeited with the smashing excellence of the play, and, next time, when he has two dollars to spare, he craftily adds it to his little savings in a toy bank, and the most “stupendous” hit New York has seen in a hundred and eleven years has to be withdrawn after a week’s run.

BUT suppose that that man had a mileage ticket.

What then? Why, as soon as the superb technique and the sparkling dialogue of the dramatist gave him that feeling of complete satiety which is such a never-failing by-product of the modern play, out he would rush.

A few nights at home would enable him to recuperate, and back he would come to enjoy another twenty minutes or so of the intoxicating pleasure. If the original play happened to be in the storehouse by that time, he would be entitled—by his mileage ticket—to a seat for the next “hit” at the same theatre.

The ideal arrangement, of course, would be if the various managements could come to some sort of understanding and consent to a species of pooling arrangement.

If this could be done, the mileage ticket would be good for any theatre, at any time, and the demand for them would infallibly be enormous. How frequently it has happened that, in the middle of the first act of one of those tense dramas with wicked millionaires in them, you have said to yourself, “After all, there’s nothing like musical comedy!” And does it not generally happen that, just as the stout comedian of “The Girl From Speonk” is being discovered by his jealous wife flirting with a blonde goddess in the chorus, you have mused wistfully, “If I get out of this alive, me for the legitimate!”

ANY doctor will tell you that the best rest is a change of work. There is no work that can compare—in its exhausting quality—with the labor of watching a modern play. To be able to switch at will from one theatre to another in the middle of a performance, would be the saving of many playgoers.

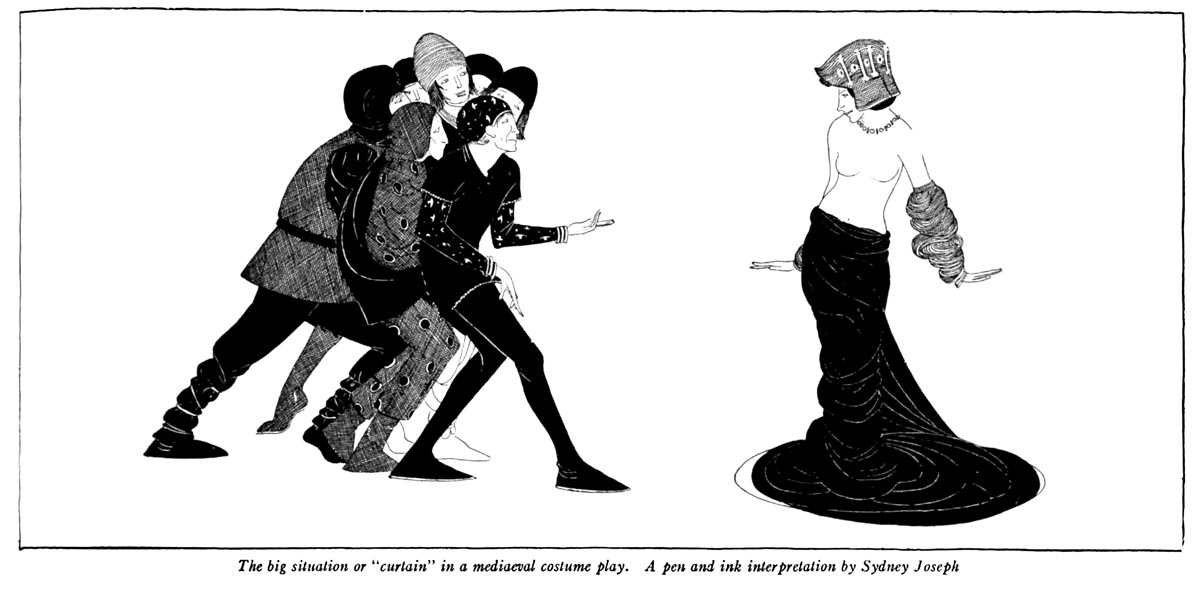

And one enormous advantage of this system would be that nobody would ever be obliged to see the last act of any piece. The flaw in most plays is that the public demands a big situation at the end of the last act but one. It is easy enough for the dramatist to cook up that big situation, but it is apparently impossible for him ever to unscramble it in the last act. Under the mileage system the entire audience would leave after applauding the big “curtain” in the penultimate act of a mediaeval costume play, and there would not have to be any last act at all. At present, the poor audience have to stay on, however reluctantly, to prevent the management from getting fifty cents of their money for nothing.

IN its operation, this new mileage system would be simplicity itself. The theatregoer would purchase from a general office a ticket for so many hours at the theatre. One night, obeying that impulse, he would stroll into a musical comedy. His ticket would be punched by the time clock at the door. Finding, after the opening chorus, that there is a German comedian in the piece, he promptly removes himself. The attendant at the clock punches his ticket again, to show to the attendant at the next theatre that the victim has used up seven minutes of his purchased time. In this way, if the victim lives, his ticket is eventually exhausted.

In the present condition of the great American drama a fastidious man might make a ten-hour ticket last out the entire season.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums