Vanity Fair, January 1916

CRUELTY TO MILLIONAIRES

By J. Plum

President of “The Foes of Music”

THIS is the age of societies for the prevention of cruelty to various classes of the community. If you smite your child with a croquet mallet or the butt end of your brassey, the Gerry Society swoops down upon you. If, in a moment of irritation, you hurl your wife’s Pomeranian from a ninth story window, numerous animal-protecting associations roll up their coat-sleeves as a preliminary to active assault. Yet nobody has ever considered the painful case of the unhappy millionaires who, simply because they happen to have amassed a fortune, are obliged by the iron laws of our modern Society to attend the Opera and go on attending until Mr. Gatti-Casazza announces that that’s all and there won’t be any more till next year.

As we walk blithely up Broadway to our motion-picture house and see a wretched millionaire being hounded into the Metropolitan Opera House, we cannot crush down a Pharisaical feeling that it serves the man right.

“Now, perhaps,” we say to ourselves, “he’s sorry he fooled a free and trusting public in the matter of that last bond issue.”

And we go on our way pitilessly.

YET somehow, do what we will, the memory of the poor devil’s haggard, wistful face haunts us. It comes between us and the screen. It spoils Mr. Chaplin’s most exuberant art for us. We feel that, richly as he has no doubt deserved it, we have no right to allow the unhappy man to suffer like this without uttering a protest. We mutter vaguely that somebody ought to do something about it.

But what can one do? There is no breaking that iron rule that enacts that every man in New York who lays claim to any social position must take a box at the Opera during the season and sit through at least two performances a week.

The only way, since we cannot cure, is to alleviate the sufferings of these luckless men.

It is only fair to the management of the Metropolitan Opera House to admit that, by providing little ante-rooms to the boxes, each containing a not uncomfortable sofa, they have done something to mitigate the severity of the punishment which they inflict. Many a poor, broken millionaire, constitutionally unable—through having been born tone-deaf—to tell the difference between Richard Wagner and Irving Berlin has been enabled to get through a performance by sneaking off when his wife was not looking and enjoying a refreshing nap in the ante-room. But even this relief is dangerous, and should not be indulged in by plethoric or absent-minded men. I can still recall the chagrin of one unfortunate plutocrat, who, waking on the sofa and finding himself in pitch darkness, proceeded to disrobe—under the pardonable impression that he was in his bedroom at home. The moment when the lights went up and the large and fashionable box-party entered the ante-room—preparatory to going home—to discover him clothed in a natty suit of B. V. D.’s, groping idly about for his pajamas, was far more dramatic than anything seen that night upon the stage.

BUT, even if there were not the danger of such contretemps, the ante-room sofa could never be anything but a partial and makeshift antidote for opera. It is no use tinkering; we must go deep down to the root of things if we are sincere in our desire to prevent this cruelty to our wealthier brethren. We must examine Grand Opera itself, and see if something cannot be done to improve it. Because it is fashionable, it need not be so painful. Many fashionable pursuits—divorce, for example, and supper-parties at the Follies Roof—are extremely pleasant.

The root-trouble with Grand Opera is that it is behind the times. We live in an age of pep and excitement, while all the operas were composed in a more leisurely and easier-pleased epoch. In the days when Wagner first discovered that you could fool some of the people all the time and that, if you cut out the tune and gave them a low G when they were expecting a high H or a Z in alt or something like that, they would take it for granted that this was good music, there were fewer counter-attractions. You either had to go to the opera or else stay at home and play whist. But nowadays, with a Mary Pickford film on each block and half a dozen farces playing within a biscuit throw, competition has grown fiercer. The only thing that keeps Opera on the map is the fact that nobody dare quit before the other fellow. Young Mr. Rockefeller meets young Mr. Morgan at the ice-cooler in the corridor and says to him, “How do you like it?” “Fine,” replies Mr. Morgan. “I particularly admired the largo movement in A sharp.” “Not so worse,” says Mr. Rockefeller. “But what I enjoyed was the pizzicato rallentando of the wood-wind.” Whereas, if they dared, they would exchange the lodge distress-sign and pussy-foot off to the Winter Garden.

ONE of the most serious troubles with Grand Opera is that you have no means of telling what the deuce it is all about. A stout gentleman comes on the stage and sings: “La-wha ta zoom ba hump na ree,” etc., and you have no means of knowing whether he is trying to tell you that the only girl he ever loved has married a social gangster or whether the trouble is that he came home after leaving his office and found that the butler had been at the port again and the cat had stolen the remains of the cold chicken. All this uncertainty might be avoided by the adoption of the ingenious moving-picture device of legends flashed on the screen. You go to see a moving-picture, and the management helps you out with such explanations as “Estelle Discovers the Dead Body” or “The Man She Married was a Mormon.” It would be perfectly simple to do that sort of thing at the Metropolitan.

Or why not additional numbers? It is generally recognized nowadays that the only songs that make a hit in a musical production are the ones written in during rehearsals. A few good, song-hits like “Same Sort of Girl” or “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to be a Soldier” would be the making of the average grand opera.

BUT it is probably too much to expect the management of the Metropolitan to take any steps of this kind. They feel that they have got a cinch. Everybody, who is anybody, has got to go to Grand Opera.

But wait! A bitter awakening is in store for them, and—by an ironical poetic justice—they have brought it on themselves by printing in a corner of all of their programmes the hint which will bring about a total abstention from opera on the part of our millionaires. Here is the extract. “The late Baron de Reuter, whose love for music was sincere and undoubted, used to say that he found as much pleasure in reading the score of an opera at home, as in hearing the music.”

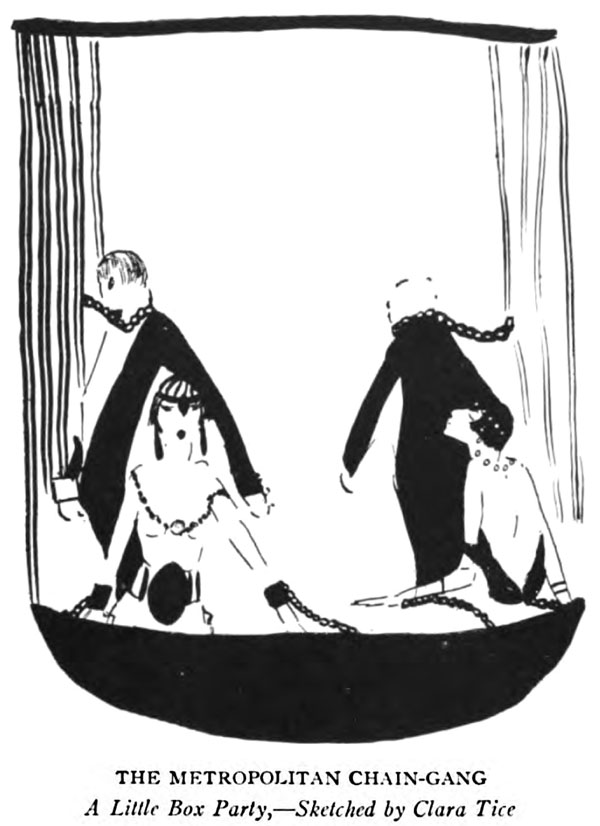

This is the loop-hole through which our sufferers may escape. “The reading,” it goes on, “does not disappoint the reader; the performance often vexes the hearer. Although the conductor may he able and eloquent, his interpretation may vex this one or that one by some unexpected choice of tempo, by some too deliberately planned nuance, by some sudden display of individual feeling that is not in sympathy with the emotional intention of the composer.” Will the poor, harassed millionaires grab at this chance? Will they! What it amounts to is that they will be able to get a high-brow reputation more easily by stopping away from the opera than by going to it. I can see them at it, these released convicts of the Grand Opera chain-gang. Their wives come to them, a mass of jewels from head to foot, and upbraid them for lounging at home in an arm-chair, in the old slippers and bathrobe. “Are you not aware, Twombley, that tonight is the opening performance of ‘Rheingold?’ ” “Perfectly, my dear. And if you have so little artistic feeling as to wish to attend, by all means do so. It’s all very well for those with low foreheads, but not for sensitive people like me. I’ve just had a telephone call from Mr. Mackay. He wants me to come round. A bunch of the other boys will be there, and we are going to read the score together.”

And he smiles a happy smile, remembering that the last time he read the score with the boys, he held four aces.

Note:

Wodehouse is once again ahead of his time; here he anticipates opera supertitles (introduced by the Canadian Opera Company in 1983) by two-thirds of a century. —Neil Midkiff

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums