Vanity Fair, February 1916

SOME THEATRICAL MYSTERIES

Described, Discussed, Dissected, But Unsolved

By P. G. Wodehouse

KING SOLOMON, if I remember rightly, put the number of things which no fellow could understand at three. If he had been a modern theatergoer, he might have found reason to revise the score-card. The theater at the present moment bristles with mysteries. Why, for instance, did a supposedly intelligent jury acquit Sir Hubert Ware? Why is there always a man in an apparently advanced stage of alcoholism in the seat behind mine when I go to see a play? Why was it worth Avery Hopwood’s while to write a play like “Sadie Love”? Why do managers advertise a performance to begin at eight-fifteen when they have no intention of raising the curtain till eight-thirty-five? Why do stage pirates always say “Aa-a-ah”? It is no good trying to explain these things. We must simply accept them.

THE Hopwood mystery is to my thinking the most puzzling of all. Here is a man with a genius for bright lines, an aptitude for farce which recalls the early days of Pinero, and every other gift which a playwright should have, deliberately nullifying his charm in order to tickle the infinitesimal portion of the public which goes to the theater to get a thrill from indecency. If there were money in this sort of thing, it might be more intelligible; but it has been proved over and over again that the public as a whole, though vague as to what it wants, has the clearest opinions as to what it does not want; and it does not want heavy-handed suggestiveness. Broadway may enjoy it, but in things theatrical the big money is not made on Broadway but on the road; and, unless the provincial taste has changed completely, there is no hope for “Sadie Love” on the road. As a matter of fact, even Broadway seems to have qualms about the piece. A distinct wail of protest went up from the daily papers on the morning after the first performance, and on the night I wandered in, unsuspecting, a pure-minded dead-head, hardened Tenderloiners were groping their way out into the fresh air between the acts, looking at each other with a stunned amazement and uttering feeble bleating noises.

THE thing is too raw. It is all very well for George Jean Nathan to say that “Hopwood’s suggestiveness is gorgeously forthright” and that “his touch is the touch of a Sacha Guitry, a Ripand Bousquet, a Max Maurey, a Lothar Schmidt, a Romain Coolus.” The point is that French covers a multitude of sins and that English is a bad medium for this sort of thing. However, Mr. Nathan was reviewing “Fair and Warmer” when he wrote what I have quoted, and many a man raves about “Fair and Warmer” to whom “Sadie Love” is considerably too adjacent to the knuckle to have any appeal. One of whom, as Artemus Ward used to say, I am which. I am prepared to bore the most casual acquaintances indefinitely with my enthusiasm for “Fair and Warmer”; but, while one may enjoy the spectacle of a man skating on thin ice, that is no reason why one should care to see the same man floundering in slush.

BUT the acting! Ah! That is something else again. Two more perfect performances of horribly difficult parts than those of Marjorie Rambeau and Pedro de Cordoba I have never seen. I stutter when I try to utter and hit the wrong keys when I try to typewrite my opinion of Miss Rambeau. I wish I could pull that French stuff, like Nathan. It would help me out so splendidly to say “Her touch is the touch of a ——” someone or other. But that sort of thing is a gift. I couldn’t do it. All I can say is that Miss Rambeau’s charm is comparable with that of ——, that her technique is fully equal to that of ——, and that her je-ne-sais-quoi and espièglerie irresistibly recall ——, and leave you to fill up the blanks yourselves. However flatteringly you fill them up you can’t go wrong. If, within the next year or so, Marjorie Rambeau is not America’s leading comedienne, I will eat the soft squashy hat which I wear to show people that I am a literary man. Aye, and my 1915 rubbers, also.

“ THE Ware Case” at Maxine Elliott’s Theater is a mystery play, but, as I have hinted, the chief mystery about it is what on earth the jury were thinking of when they acquitted Sir Hubert Ware of the murder of his wife’s brother. If ever a man looked as if he had murdered his whole family and a few of the neighbors, it was Lou-Tellegen in the witness-box in Act III. There was not a hole in the case for the prosecution. Sir Hubert’s alibi took the count at the first punch; he was the only person who had anything to gain from Eustace Ede’s death; and it was shown that his favorite reading was a book on French crime, a page of which—treating of a murder on exactly similar lines—he had turned down or marked with a pencil or something. There was other evidence, too, but the twelve fat-headed men and true let him go free. I have a suspicion that George Pleydell, the author, was working off a delicate slam at the stupidity of the average theater audience, for the audience at the Maxine Elliott’s is supposed to be the jury in the trial scene.

In London the part of Sir Hubert was played by Gerald du Maurier and was, I imagine, written round his personality. At any rate, for all his skill, Lou-Tellegen in the role conveys a kind of misfit impression, as if—supposing such a terrible thing were possible—he were wearing a ready-made suit. It may be that his accent is responsible for sending me away with that impression. A line has been inserted in the middle of the third act to the effect that Sir Hubert spent his youth in France, but it comes too late to make the phenomenon of a British baronet calling his friends “Dommee” and “my tear vellow” really convincing. Not but what Mr. Tellegen makes a pretty good showing linguistically for one who, as my programme informs me, is of Greek Dutch extraction and French up-bringing. It is going some to say even “my tear vellow” with any conviction after jockeying at the start like that.

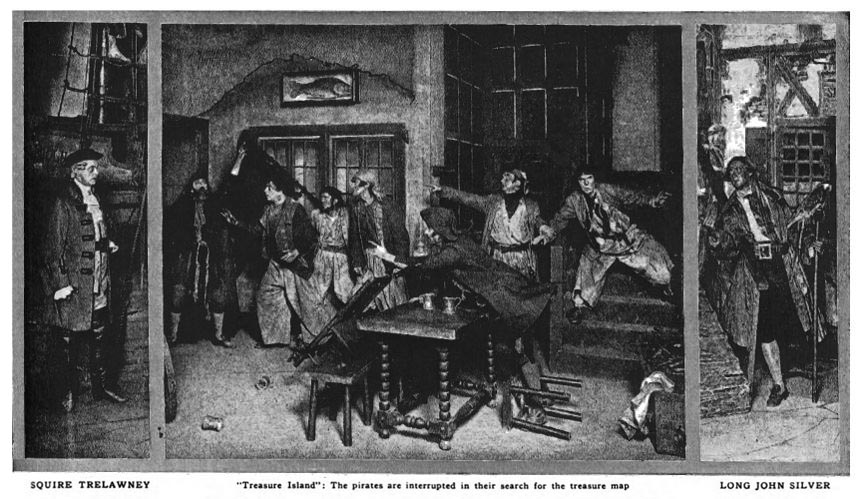

IT is not difficult to understand why “Treasure Island” has made a success at the Punch and Judy. Everybody loves “Treasure Island.” The mystery here is why Jules Eckert Goodman ignored so much of what is best in the story when making his dramatization. If he has any recollection of his boyhood, when, I take it, he read the book first, he must have known that great scene where Jim hides in the apple barrel while the pirates chat on the deck all round him could not possibly be made too long. It is one of those rare situations where desultory conversation enhances the drama. The longer the pirates sit there, chatting at their ease about old times, the greater becomes the suspense. But Mr. Goodman has condensed the scene into a few minutes of rapid action. Jim is in and out of the barrel in a flash. Again, where Silver shoots George Merry when the latter is trying to head a revolt of the pirates against their leader. In the book Merry falls writhing into the open trench where the treasure should have been but is not, and Silver remarks dreamily: “You always were a pushing young fellow, George!” It is one of those lines which drive home a man’s character with an unforgettable punch. In the play Merry staggers into the wings, and Silver says nothing. One feels the sense of something missing. There is a sort of bleakness. That is the fault of the play all through, after the first act. It is a mere succession of scenes, every one of them too short. Which, considering that the curtain rises at eight-thirty-five and falls the last time at five minutes to eleven, is inexcusable. What was your hurry, Jules?

In effect, the story—the most gorgeous that ever was—is subordinated to the scenery which, to give it its due, is superb. But not even the Hispaniola, tossing on the most convincing waves, could reconcile me to the cutting of the dialogue between Jim and Hands, the boatswain, There, in the book, is an intensely dramatic scene, every line of which would stand transference to the stage; but in the play the only dialogue is a lot of “Aa—a-ahs!” Which brings us to the curiously important part which that exclamation plays in the life of the stage pirate. In “Treasure Island” at the Punch and Judy, Silver’s gang could not do the simplest thing without saying “Aa-a-ah!” They all said it, and they all said it at the same time. They said it when they were pleased, and they said it when they were annoyed, they said it when things were coming their way, and they said it when they were baffled. They probably said it in their sleep. The result was that, just when they needed their wind most—to see them through a stiff fight, they collapsed through sheer want of breath and had it put all over them by numerically inferior antagonists. There is a lesson in this for all of us. Suppose Jess Willard had spent his time saying “Aa-a-ah!” at Havana! Would he be champion of the world to-day? Suppose Henry Ford had developed the habit of saying “Aa-a-ah!” Would he have stopped the war as he did? Certainly not.

As far as I am concerned, actors endeavoring to act the characters in “Treasure Island” attempt the impossible. Nobody could ever come up to my standard for—say—John Silver or Pew. But Edward Emery's attempt at Silver very nearly satisfied me. (Very good, Eddie, very good.) And I am not sure that W. J. Ferguson was not my old friend George Merry to the life.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums