Vanity Fair, September 1914

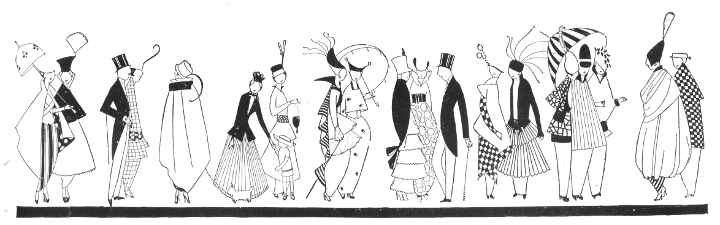

THE KNUTS O’ LONDON

Desperate Fellows All, and the Distinction

Between the “Knut” and the “Blood”

Nuts, By P. G. Wodehouse Drawings by Fish

I’M GILBERT, the filbert,

I’M GILBERT, the filbert,

The nut with a k.,

The pride of Piccadilly,

The blasé roué;

Oh, Hades, the ladies,

They’d leave their wooden huts

For Gilbert, the filbert,

The colonel of the nuts.

So runs the refrain of the song which all London is whistling at the present moment, and

American visitors probably wonder why Gilbert should apparently take pride in the absence of

sanity implied by his description of himself as a Nut. But in England the word “nut” has a

different meaning. The Nut of London is the descendant of the Beau, the Buck, the Macaroni, the

Johnnie, the Swell, and the Dude.

So runs the refrain of the song which all London is whistling at the present moment, and

American visitors probably wonder why Gilbert should apparently take pride in the absence of

sanity implied by his description of himself as a Nut. But in England the word “nut” has a

different meaning. The Nut of London is the descendant of the Beau, the Buck, the Macaroni, the

Johnnie, the Swell, and the Dude.

Nobody knows how the word came into existence in its present sense. London seemed to awake one morning convinced that the only proper term for the young man cutting a swathe through its midst on his father’s money was the term “Nut,”—or “Knut,” as you must spell it to be in the movement. Overnight it had been calling these young men “Johnnies,” “boys” and “lads.”

George Grossmith was the first to emphasize the distinction between the Nut and the Blood. The Blood was a young man who caused riots in restaurants: the Nut is too listless to do anything so energetic. For listlessness and a certain air of world-weariness, combined with a colored collar, a small moustache, a drooping carriage, the minimum of frontal development, and a high-power racing-car, are the chief qualifications of the Nut. He is bored to death, but he does it simply because it’s done.

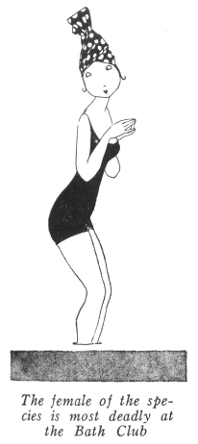

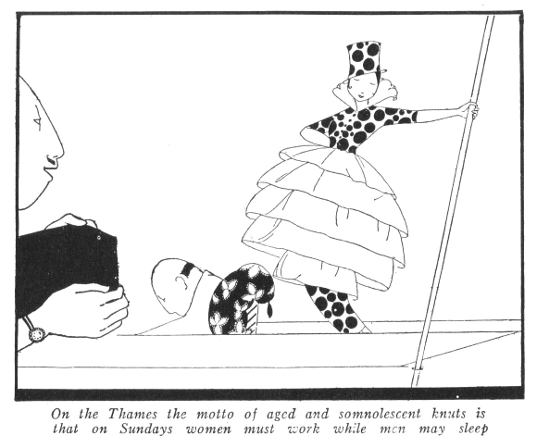

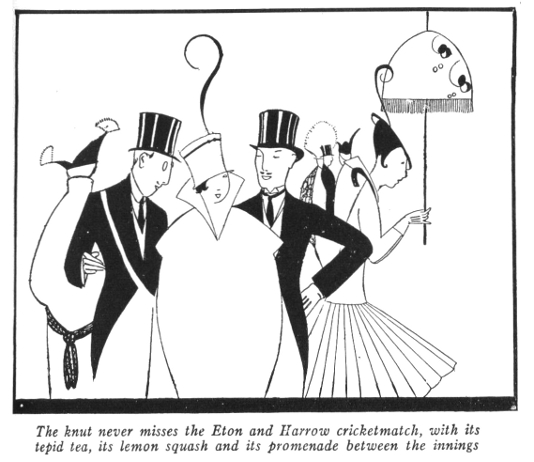

The Nut is faithful to tradition. He appears on Church Parade: he never misses the Eton and Harrow cricket-match with its promenade between the innings: on Sundays aged and decrepit Nuts may be seen in Boulter’s Lock, dreaming peacefully while their female equivalents, the flappers, wield the punt-poles, for women must work though men may sleep, and the Bath Club, with its mixed bathing, is one of his chosen retreats.

His chief forms of relaxation are dancing and bread-throwing. The only time a Nut really sits up and begins to display animation is when a hard roll, thrown by a friend across the table, takes him in the eye, and he reaches out for another to throw back.

WHAT becomes of the Nuts is as great a problem as what becomes of the pins. Perhaps they die:

perhaps they turn into something else: though it is difficult to imagine a genuine Nut being

anything but himself. With the Blood it was different. After he had thrown a sufficient number of

plates at a sufficient number of waiters, and wrenched enough knockers from their doors to

soothe his too energetic soul, he turned naturally to pursuits where energy was a commercial

asset. But the Nut is not a product of misdirected energy: he is a sort of clam, endowed with just

enough power of motion to enable him to get into a taxicab and say “Murray’s.” The most

plausible theory is that he just evaporates like a fog, and somebody, passing by, sees his clothes

lying there and takes them away.

WHAT becomes of the Nuts is as great a problem as what becomes of the pins. Perhaps they die:

perhaps they turn into something else: though it is difficult to imagine a genuine Nut being

anything but himself. With the Blood it was different. After he had thrown a sufficient number of

plates at a sufficient number of waiters, and wrenched enough knockers from their doors to

soothe his too energetic soul, he turned naturally to pursuits where energy was a commercial

asset. But the Nut is not a product of misdirected energy: he is a sort of clam, endowed with just

enough power of motion to enable him to get into a taxicab and say “Murray’s.” The most

plausible theory is that he just evaporates like a fog, and somebody, passing by, sees his clothes

lying there and takes them away.

He speaks a language of his own. Pleasant happenings “brace him awfully”: unpleasant happenings “feed” him. A friend is a “stout fellow”: an enemy a “tick.” Just at present he affects a few Americanisms, and will attach the word “some” to practically every noun he uses.

Notes:

Gilbert the filbert: Character created by Basil Hallam (1889–1916) in The Passing Show of 1914, a revue which opened at the Palace Theatre, London, on 20 April 1914. His introductory song was composed by Herman Finck, with lyrics by Arthur Wimperis. An American edition of the sheet music is online at this link.

George Grossmith [Jr]: (1874–1935), multi-talented actor/writer/producer in British musical comedy, son of the creator of many of the Gilbert and Sullivan patter roles, and later a collaborator with Wodehouse on shows such as The Cabaret Girl and The Beauty Prize.

frontal development: the frontal lobes of the brain, then considered the site of the intellect

Boulter’s Lock: on the Thames near Maidenhead, a popular site for boating parties in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Murray’s: night club in Beak Street, London, opened in 1913.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums