Vanity Fair, January 1918

The Poor Old Drama

And Why the Theatre Ushers are Having the Time of Their Lives

By P. G. WODEHOUSE

DIRTY weather, mates, very dirty weather. Storm-clouds are gathering and cold winds howl along the Rialto, causing theatrical managers to huddle into their fur coats and think of the happier days when they were office-boys; while ticket-speculators sob on each other’s necks and wish they had stuck to some other branch of crime, like burglary or sneaking milk-cans, where a fellow really could make enough to keep himself in cigars and afford an occasional visit to Childs’.

For the Theatre has got it right on the back collar-stud. What with the war-tax and the income-tax and the super-tax and Red Cross Benefits and Liberty Loans and women who knit instead of attending matinees, the Drama is experiencing the worst slump in many years, and the writings of a dramatic critic on a monthly magazine are coming to have a merely archæological interest.

The present conditions have given me personally precisely the same sensations as I used to have when I had a job writing encore verses for the old-fashioned type of topical song at the Gaiety Theatre in London. I would write them with the sickening feeling at the back of my mind that by the time they were presented to the public they would be out of date and possess no meaning.

THE fellows on the daily papers are all right. Even nowadays a piece generally manages to run for two consecutive nights. But what is the monthly-magazine theatre-hound to do? Is an intelligent and discriminating public going to be interested on December the twenty-third, when this issue of Vanity Fair will appear, to know what I thought of a play that died on November the twenty-ninth?

Would you like a thoughtful essay on “The Old Country,” or would you prefer a carefully-reasoned thesis on “Antony In Wonderland”? Can I fascinate you with my meditations on “The Rescuing Angel”, or shall I analyse “Barbara”, which played eighteen performances in this sorrow-stricken burg? Take it by and large, it is getting to be a pretty tough world for the goggle-eyed lads who edge into the theatre on their intellectual faces in order to enrich the nation’s store of dramatic criticism.

Since the beginning of the season seventy-six productions have been put on in this frost-bitten metropolis. Forty-one—count ’em! Forty-one solid, individual productions—have expired with low gurgles. And of the thirty-five which are still playing, fifteen have been presented within the last two weeks and are probably being removed as I write these words.

Such carnage has never been known. One black Saturday night ten shows closed simultaneously: and, the way things are looking at present, that Saturday night will soon become famous as the night when only ten shows closed. It begins to look as though nothing except the draft system for audiences would enable managers to get through the winter.

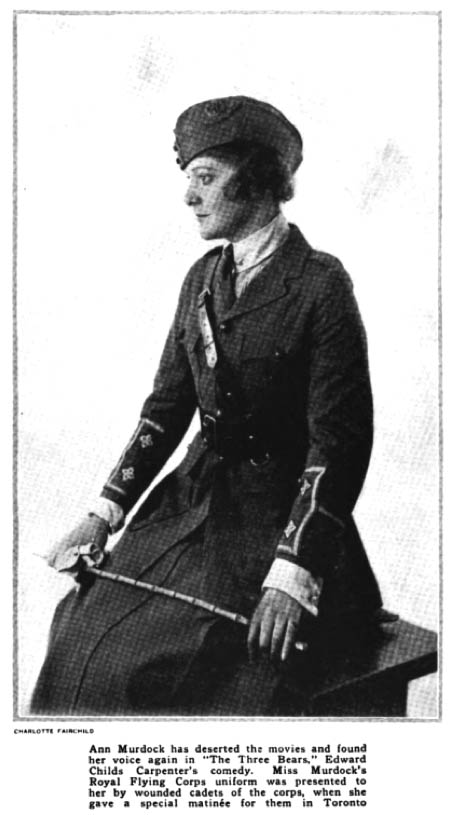

Stars have had a particularly tough time of late. William Faversham Lasted two weeks; Henry Miller one; Billie Burke survived thirty-three performances; Laura Hope Crews managed to do four weeks; Alice Nielsen only achieved two; Grace George played “Eve’s Daughter” thirty-four times; and Marie Doro was unable, as stated above, to support “Barbara” for more than eighteen performances. “Rambler Rose,” with Julia Sanderson and Joseph Cawthorn was an admitted failure, and Donald Brian’s “Her Regiment” looks wobbly. Fred Stone, of course, would play to capacity if a German army were marching up Broadway. Of the remaining five, Ann Murdock in “The Three Bears,” Mrs. Fiske in “Madame Sand,” Leo Ditrichstein in “The King,” and John Drew and Margaret Illington in the revival of “The Gay Lord Quex,” it is too early to speak with any certainty.

THERE was a disposition on the part of the critics of the daily papers to treat “The Gay Lord Quex” with a certain affable condescension as a relic of the bygone day when plays were crude affairs far below the mental level of the modern bean.

There was a good deal of the “Dear quaint old Pinero” sort of thing, and a general inclination to say that that kind of stuff may have been all right twenty years ago but that we enlightened nibs of 1917 could not be expected to take it seriously. Well, if I am expected to get up and give three ringing cheers because the modern dramatist, instead of turning out Gay Lord Quexes, is giving us “The Love Drive,” “Mother Carey’s Chickens,” and “Romance and Arabella,” count me out. That is all I say.

I am not angry about it, not what you would call profoundly peeved. All I say is, count me out.

To me—a low-brow unfit for decent society—“The Gay Lord Quex,” coming on the crest of a wave of the utterest piffle that ever poisoned a critic’s life, was like an ice-cream soda descending from the skies on a drouthy camel in the Sahara. I just sat and let it soak in through the pores. John Drew, I thought, had never acted better or had a better part. Let us be modern and superior by all means, but, for the love of Heaven, let’s wait till we scramble out of a theatrical season like the present one before we start saying that Pinero isn’t good enough for us.

A CONSCIENTIOUS Ouija-Board, if consulted as to the fate of “Madame Sand,” would probably prophesy success and prosperity. Mrs. Fiske has a part that suits her, and one of which she can make a great deal. The public that likes to see George Arliss bring the great ones of the past back to life ought to enjoy the spectacle of George Sand, Alfred de Musset, Chopin, and Heine gathered together on one stage. And Madame Sand’s career is intrinsically interesting. As Georgia O’Ramey says in “Leave It To Jane,” “a girl certainly got away with an awful lot — in them days.”

“The King,” which presents Leo Ditrichstein in the familiar role of a great—and, this time, a rather rollicking, even rowdy—lover, is one of those lively French farces which the adaptor for the American stage works on with a gas-mask and a large blue pencil, conscious, as he toils, that the finest Force in the world will be waiting at the doors of the theatre to pull the place if he doesn’t tone the little opus down with a sufficiently firm hand. Being designed principally as a bludgeoning satire of the inner workings of French politics, the piece loses a good deal of its force when shown over here; but it is certainly not necessary to be interested in the seamy side of French politics to appreciate its broadly farcical situations.

As Louis Sherwin aptly remarked, there is plenty of fun in “The King” to enjoy, without regretting the jokes that might have been. Leo Ditrichstein gives another of his easy, polished performances: and it really looks as if he were going to break this season’s etiquette for stars and have a big success. Robert McWade is excellent in the part of a loud-mouthed Socialist.

“The Three Bears,” in which Ann Murdock reappears on Broadway, is another of those pleasantly whimsical comedies with which Edward Childs Carpenter seems to be trying to establish himself as an American Barrie. As an entertainment it falls midway between the author’s “Cinderella Man” and “The Pipes of Pan,” being a good deal better than the second but not quite so good as the first. It suffers a little from having the same root-idea as “At the Barn,” in which Marie Tempest made a brief appearance in New York. Ann Murdock is the mainstay of the piece, which is always amusing but pretty slight and fragile to be used as a barque in which to weather the present theatrical blizzard.

FROM time to time, as you make your way through the Slough of Despond which used to be the gay and glittering Rialto, you hear amidst the groans of the sufferers a statement that “Broken Threads” at the Fulton is doing good business. It may be so. It is a fairly interesting melodrama by Ernest Wilkes, which shows among other things that, in spite of its well-known climate which ought to soften the hearts of the inhabitants to the calibre of little children, California can produce some pretty low-down individuals. Cyril Keightley is good as the persecuted hero, and two smaller parts that are notably well played are the Dick Brenton of William Roselle and the William Budlong of Paul Stanton.

Grace George, coming to the bat for the second time, has done better. “L’Elevation,” the latest work of Henry Bernstein, is a thoughtful and interesting piece of work, but whether there will be public support for so gloomy a piece in these hard times is doubtful. Miss George’s part could not be better played, and Lionel Atwill and Holbrook Blinn are both admirable, but the whole play is so sad that most people are likely to decide that a pleasanter evening is to be spent at Jack Norworth’s bright little “Odds and Ends,” which goes one step further in intimacy than “Hitchy-Koo” and shows promise of being just as successful.

The recent history of the London stage affords a good indication of the sort of entertainment which the citizens of a country at war like to see; and revue of the genial, loose-jointed type is likely to be more and more the fashion for many months to come. “Odds and Ends” is a very good specimen of the sort of thing which has been doing so well in London.

FARCES continue to come and go. One that looks as if it might stay is Fred Jackson’s “Losing Eloise,” with Charles Cherry as its backbone. But you can’t be sure of anything this season. Let us, however, end on a cheerful note. Whoever else is unhappy, the theatre ushers are having the time of their lives. Their job has lost all the monotony which used to spoil it. They can count on having something new to see every other week.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums