Vanity Fair, August 1916

THE THREE-IN-ONE PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE

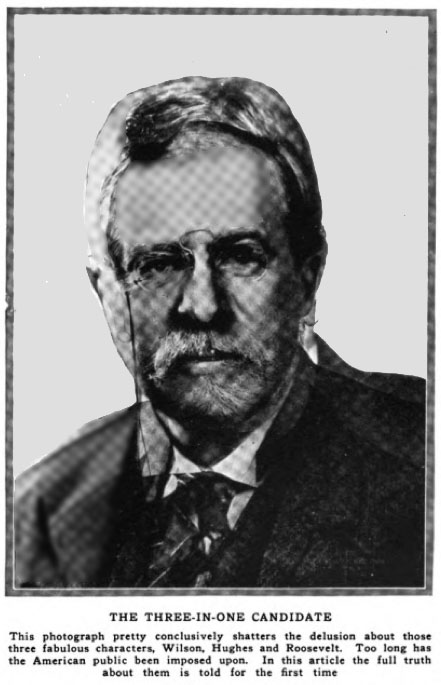

An Exposure of the Myth About Hughes, and Wilson, and Roosevelt

By P. Brooke-Haven

THE man with the rather wild-looking eyes seated himself beside me and opened conversation, as if we had been boys together: “Well, Bill,” he began. (My name is not Bill, but I assumed that he spoke figuratively, as it were.) “Well, Bill, who’s going to get your vote?”

“I beg your pardon?” I said. The question seemed to me to require footnotes, and perhaps a glossary.

“Thisyer Wilson, or thisyer Hughes, or thisyer Roosevelt, if they get him to run,” he explained.

I HOLD strong political views, and I was glad to be given an opportunity of expressing them to an intelligent audience.

“Before answering that question,” I said, “it might be as well if I were to sketch briefly for your benefit the causes which have led me to decide to cast my vote for the candidate whom I have selected as most worthy of it. I will divide my subject into three heads. In the first place, here we have three men of great”——

He chucked offensively. For no reason whatever that I could see he appeared to consider that I had said something ridiculous.

“So you’re not wise to the fake?” he scoffed.

“In what respect?” I asked.

“Well, I don’t wonder. I only got onto it myself a few days ago. By the merest chance I unearthed this extraordinary conspiracy against the welfare of the common people and detected this entirely unsuspected plot. You speak of Hughes and Wilson and Roosevelt as three men. And that is how all but one of the millions of your fellow-countrymen think of him. I am the one exception. There are no such persons as Hughes and Wilson and Roosevelt. These names are mere aliases of one man—the uncrowned King of America, the man who controls both Democratic and Republican machines, and who, after an enjoyable four years at the White House as President Wilson, and four before that as President Roosevelt, is now about to disguise himself behind a mass of facial flora and embark on another term, as President Hughes.” He waved me down majestically. “Let me tell you how I arrived at this conclusion. In the first place, let me point out exactly where you stand in this political game. You look on yourself as an independent voter, but, coming down to case cards, what sort of a show have you got? You can’t vote for the man you really want for President.

“If you had a free choice, you would say to yourself: ‘Well, there’s old Jim Higgins who was at school with me. He’s a pretty good sort of old scout, and I owe him fifty dollars. Besides, my wife’s brother married his niece. I guess I’ll vote for Jim for president.’ You can’t do that. You have got to vote for the man chosen by the Republican Convention, or the man chosen by the Democratic Convention, or the man chosen by the Progressive Convention. Well, that’s how you stand, see? Now, you can see for yourself that it wouldn’t be hard for a fellow with ambition and plenty of money to get control of all three machines, give the other guys enough to keep them quiet, and have himself nominated by all of them every four years. But the weakness in that scheme is that the public like a fight and like a change. They wouldn’t stand for this fellow—we’ll call him Smith—bobbing up again and again every time there was an election. He has to use his wits. Pretty soon he sees the solution. I call your attention once more to the very significant fact that President Wilson and President Roosevelt are clean-shaved and wear glasses, while Judge Hughes has whiskers and doesn’t wear glasses. Why, an elementary talent for disguise is all that’s needed. Note this. Thisyer Wilson, and thisyer Hughes, and thisyer Roosevelt have never been seen together by the public. Never! When Wilson’s here, Hughes is supposed to be there. When Wilson’s there, Roosevelt is here.

“BUT I’m not basing my theory on just that evidence alone. It’s their speeches that put me on the right track. Even you must have noticed something odd about those speeches. They don’t sound right. They are supposed to be made by three men holding opposite and conflicting political opinions, and yet they sound like a trio of old college chums harmonising ‘The Old Oaken Bucket.’

“Judge for yourself. Here’s thisyer Hughes addressing the Wissahicken Seminary for Young Ladies. I quote from memory:

“ ‘I hope, my dear children, that you will always respect the Flag of our Fathers. It is a nice flag. I like it. I should be extremely cross with anyone who insulted the flag. It may be a peculiarity of mine, but I could never be really friendly with anyone who pulled the flag down and jumped on it. There would be something in my manner when we next met which would make him see at once that I did not like him.

“AND here’s thisyer Wilson, addressing the Weehawken Correspondence School of Intensive Chicken-Farming. Pardon me if I again quote from memory:

“ ‘Gentlemen, I should like to say a few kind and encouraging words about the Flag of our Fathers. It may be weak of me, but I respect our flag. If anyone picked on our flag I should give him a nasty look. Unconventional as my attitude may appear, if anyone took the flag down and chewed holes in it, I should cut him dead. This may seem brutal to you, gentlemen, but it would be my own firm and unfaltering attitude.’

“And then there’s thisyer Roosevelt, who delivered that impassioned address to the United Photographers of Irene Castle, at Manhasset, Long Island. I only remember the speech vaguely:

“ ‘And any man who polishes his russet walking shoes with the Flag of our Fathers, or who wraps up Swiss cheese in it, is—and I don’t care who hears me say it—a mean, horrid, sly, deceitful thing—so, there now.”

“NOW weren’t those three speeches made by the same man? The internal evidence is overwhelming. You get that same curious idea in all of them that there is something remarkable in the notion of respecting the American flag, and that the speaker is the only fellow who has got onto the scheme of feeling well-disposed towards it. But that is not all. You remember that Hughes, in his speech to the Seattle Kindergarten, said that he advocated an ‘undivided America,’ and that Wilson, speaking to the Nome Newsboys, said that an ‘undivided America’ was the main plank in his platform; while Roosevelt said, in speaking to the lady waitresses at the Fourteenth Street Child’s, that an ‘undivided America’ was the only kind he would accept as a gift.

“All this I consider absolutely convincing. There can’t be three different men in this country who would get all puffed up with pride because they thought America ought not to be divided. Nobody ever said it should be divided. Nobody would know how to start dividing it if they did suggest it. You can’t tell me that a fool idea like that would occur simultaneously to three grown men.”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums