The Strand Magazine, November 1924

THE side-door leading into the smoking-room opened, and the golf-club’s popular and energetic secretary came trotting down the steps on to the terrace above the ninth green. As he reached the gravel, a wandering puff of wind blew the door to with a sharp report, and the Oldest Member, who had been dozing in a chair over his “Wodehouse on the Niblick,” unclosed his eyes, blinking in the strong light. He perceived the secretary skimming to and fro like a questing dog.

“You have lost something?” he inquired, courteously.

“Yes, a book. I wish,” said the secretary, annoyed, “that people would leave things alone. You haven’t seen a novel called ‘The Man With the Missing Eyeball’ anywhere about, have you? I’ll swear I left it on one of these seats when I went in to lunch.”

“You are better without it,” said the sage, with a touch of austerity. “I do not approve of these trashy works of fiction. How much more profitably would your time be spent in mastering the contents of such a volume as I hold in my hand! This is the real literature.”

The secretary drew nearer, peering discontentedly about him; and as he approached the Oldest Member sniffed inquiringly.

“What,” he said, “is that odour of——? Ah, I see that you are wearing them in your buttonhole. White violets,” he murmured. “White violets. Dear me!”

The secretary smirked.

“A girl gave them to me,” he said, coyly. “Nice, aren’t they?” He squinted down complacently at the flowers, thus missing a sudden sinister gleam in the Oldest Member’s eye—a gleam which, had he been on his guard, would have sent him scudding over the horizon; for it was the gleam which told that the sage had been reminded of a story.

“White violets,” said the Oldest Member, in a meditative voice. “A curious coincidence that you should be wearing white violets and looking for a work of fiction. The combination brings irresistibly to my mind——”

Realizing his peril too late, the secretary started violently. A gentle hand urged him into the adjoining chair.

“——the story,” proceeded the Oldest Member, “of William Bates, Jane Packard, and Rodney Spelvin.”

The secretary drew a deep breath of relief, and the careworn look left his face.

“It’s all right,” he said, briskly. “You told me that one only the other day. I remember every word of it. Jane Packard got engaged to Rodney Spelvin, the poet, but her better feelings prevailed in time, and she broke it off and married Bates, who was a golfer. I recall the whole thing distinctly. This man Bates was an unromantic sort of chap, but he loved Jane Packard devotedly. Bless my soul, how it all comes back to me! No need to tell it me at all.”

“What I am about to relate now,” said the sage, tightening his grip on the other’s coat-sleeve, “is another story about William Bates, Jane Packard, and Rodney Spelvin.”

INASMUCH (said the Oldest Member) as you have not forgotten the events leading up to the marriage of William Bates and Jane Packard, I will not repeat them. All I need say is that that curious spasm of romantic sentiment which had caused Jane to fall temporarily under the spell of a man who was not only a poet but actually a non-golfer appeared to have passed completely away, leaving no trace behind. From the day she broke off her engagement to Spelvin and plighted her troth to young Bates, nothing could have been more eminently sane and satisfactory than her behaviour. She seemed entirely her old self once more. Two hours after William had led her down the aisle, she and he were out on the links, playing off the final of the Mixed Foursomes, which—and we all thought it the best of omens for their married happiness—they won hands down. A deputation of all that was best and fairest in the village then escorted them to the station to see them off on their honeymoon, which was to be spent in a series of visits to well-known courses throughout the country.

Before the train left, I took young William aside for a moment. I had known both him and Jane since childhood, and the success of their union was very near my heart.

“William,” I said, “a word with you.”

“Make it snappy,” said William.

“You have learned by this time,” I said, “that there is a strong romantic streak in Jane. It may not appear on the surface, but it is there. And this romantic streak will cause her, like so many wives, to attach an exaggerated importance to what may seem to you trivial things. She will expect from her husband not only love and a constant tender solicitude——”

“Speed it up,” urged William.

“What I am trying to say is that, after the habit of wives, she will expect you to remember each year the anniversary of your wedding day, and will be madder than a wet hen if you forget it.”

“That’s all right. I thought of that myself.”

“It is not all right,” I insisted. “Unless you take the most earnest precautions, you are absolutely certain to forget. A year from now you will come down to breakfast, and Jane will say to you, ‘Do you know what day it is to-day?’ and you will answer ‘Tuesday’ and reach for the ham and eggs, thus inflicting on her gentle heart a wound from which it will not readily recover.”

“Nothing like it,” said William, with extraordinary confidence. “I’ve got a system calculated to beat the game every time. You know how fond Jane is of white violets?”

“Is she?”

“She loves ’em. The bloke Spelvin used to give her a bunch every day. That’s how I got the idea. Nothing like learning the shots from your opponent. I’ve arranged with a florist that a bunch of white violets is to be shipped to Jane every year on this day. I paid five years in advance. I am, therefore, speaking in the most conservative spirit, on velvet. Even if I forget the day, the violets will be there to remind me. I’ve looked at it from every angle, and I don’t see how it can fail. Tell me frankly, is the scheme a wam or is it not?”

“A most excellent plan,” I said, relieved. And the next moment the train came in. I left the station with my mind at rest. It seemed to me that the only possible obstacle to the complete felicity of the young couple had been removed.

JANE and William returned in due season from their honeymoon, and settled down to the normal life of a healthy young couple. Each day they did their round in the morning and their two rounds in the afternoon, and after dinner they would sit hand in hand in the peaceful dusk, reminding one another of the best shots they had brought off at the various holes. Jane would describe to William how she got out of the bunker on the fifth, and William would describe to Jane the low raking wind-cheater he did on the seventh, and then for a moment they would fall into that blissful silence which only true lovers know, until William, illustrating his remarks with a walking-stick, would show Jane how he did that pin-splitter with the mashie on the sixteenth. An ideally happy union, one would have said.

But all the while a little cloud was gathering. As the anniversary of their wedding-day approached, a fear began to creep into Jane’s heart that William was going to forget it. The perfect husband does not wait till the dawning of the actual day to introduce the anniversary motif into his conversation. As long as a week in advance he is apt to say, dreamily, “About this time a year ago I was getting the old silk hat polished up for the wedding,” or “Just about now, a year ago, they sent home the sponge-bag trousers, as worn, and I tried them on in front of the looking-glass.” But William said none of these things. Not even on the night before the all-important date did he make any allusion to it, and it was with a dull feeling of foreboding that Jane came down to breakfast next morning.

She was first at the table, and was pouring out the coffee when William entered. He opened the morning paper and started to peruse its contents in silence. Not a yip did he let out of him to the effect that this was the maddest, merriest day of all the glad new year.

“William,” said Jane.

“Hullo?”

“William,” said Jane, and her voice trembled a little, “what day is it to-day?”

William looked at her over the paper, surprised.

“Wednesday, old girl,” he replied. “Don’t you remember that yesterday was Tuesday? Shocking memory you’ve got.”

He then reached out for the sausages and bacon and resumed his reading.

“Jane,” he said, suddenly. “Jane, old girl, there’s something I want to tell you.”

“Yes?” said Jane, her heart beginning to flutter.

“Something important.”

“Yes?”

“It’s about these sausages. They are the very best,” said William, earnestly, “that I have ever bitten. Where did you get them?”

“From Brownlow.”

“Stick to him,” said William.

Jane rose from the table and wandered out into the garden. The sun shone gaily, but for her the day was bleak and cold. That William loved her she did not doubt. But that streak of romance in her demanded something more than mere placid love. And when she realized that the poor mutt with whom she had linked her lot had forgotten the anniversary of their wedding-day first crack out of the box, her woman’s heart was so wounded that for two pins she could have beaned him with a brick.

It was while she was still brooding in this hostile fashion that she perceived the postman coming up the garden. She went to meet him, and was handed a couple of circulars and a mysterious parcel. She broke the string, and behold! a cardboard box containing white violets.

Jane was surprised. Who could be sending her white violets? No message accompanied them. There was no clue whatever to their origin. Even the name of the florist had been omitted.

“Now, who——?” mused Jane, and suddenly started as if she had received a blow. Rodney Spelvin! Yes, it must be he. How many a bunch of white violets had he given her in the brief course of their engagement! This was his poetic way of showing her that he had not forgotten. All was over between them, she had handed him his hat and given him the air, but he still remembered.

Jane was a good and dutiful wife. She loved her William, and no others need apply. Nevertheless, she was a woman. She looked about her cautiously. There was nobody in sight. She streaked up to her room and put the violets in water. And that night, before she went to bed, she gazed at them for several minutes with eyes that were a little moist. Poor Rodney! He could be nothing to her now, of course, but a dear lost friend; but he had been a good old scout in his day.

IT is not my purpose to weary you with repetitious detail in this narrative. I will, therefore, merely state that the next year and the next year and the year after that precisely the same thing took place in the Bateses’ home. Punctually every September the seventh William placidly forgot, and punctually every September the seventh the sender of the violets remembered. It was about a month after the fifth anniversary, when William had got his handicap down to nine and little Braid Vardon Bates, their only child, had celebrated his fourth birthday, that Rodney Spelvin, who had hitherto confined himself to poetry, broke out in a new place and inflicted upon the citizenry a novel entitled “The Purple Fan.”

I saw the announcement of the publication in the papers; but beyond a passing resolve that nothing would induce me to read the thing I thought no more of the matter. It is always thus with life’s really significant happenings. Fate sneaks its deadliest wallops in on us with such seeming nonchalance. How could I guess what that book was to do to the married happiness of Jane and William Bates?

In deciding not to read “The Purple Fan” I had, I was to discover, over-estimated my powers of resistance. Rodney Spelvin’s novel turned out to be one of those things which it is impossible not to read. Within a week of its appearance it had begun to go through the country like Spanish influenza; and, much as I desired to avoid it, a perusal was forced on me by sheer weight of mass-thinking. Every paper that I picked up contained reviews of the book, references to it, letters from the clergy denouncing it; and when I read that three hundred and sixteen mothers had signed a petition to the authorities to have it suppressed, I was reluctantly compelled to spring the necessary cash and purchase a copy.

I had not expected to enjoy it, and I did not. Written in the neodecadent style, which is so popular nowadays, its preciosity offended me; and I particularly objected to its heroine, a young woman of a type which, if met in real life, only ingrained chivalry could have prevented a normal man from kicking extremely hard. Having skimmed through it, I gave my copy to the man who came to inspect the drains. If I had any feeling about the thing, it was a reflection that, if Rodney Spelvin had had to get a novel out of his system, this was just the sort of novel he was bound to write. I remember experiencing a thankfulness that he had gone so entirely out of Jane’s life. How little I knew!

JANE, like every other woman in the village, had bought her copy of “The Purple Fan.” She read it surreptitiously, keeping it concealed, when not in use, beneath a cushion on the Chesterfield. It was not its general tone that caused her to do this, but rather the subconscious feeling that she, a good wife, ought not to be deriving quite so much enjoyment from the work of a man who had occupied for a time such a romantic place in her life.

For Jane, unlike myself, adored the book. Eulalie French, its heroine, whose appeal I had so missed, seemed to her the most fascinating creature she had ever encountered.

She had read the thing through six times when, going up to town one day to do some shopping, she ran into Rodney Spelvin. They found themselves standing side by side on the pavement, waiting for the traffic to pass.

“Rodney!” gasped Jane.

It was a difficult moment for Rodney Spelvin. Five years had passed since he had last seen Jane, and in those five years so many delightful creatures had made a fuss of him that the memory of the girl to whom he had once been engaged for a few weeks had become a little blurred. In fact, not to put too fine a point on it, he had forgotten Jane altogether. The fact that she had addressed him by his first name seemed to argue that they must have met at some time somewhere; but, though he strained his brain, absolutely nothing stirred.

The situation was one that might have embarrassed another man, but Rodney Spelvin was a quick thinker. He saw at a glance that Jane was an extremely pretty girl, and it was his guiding rule in life never to let anything like that get past him. So he clasped her hand warmly, allowed an expression of amazed delight to sweep over his face, and gazed tensely into her eyes.

“You!” he murmured, playing it safe. “You, little one!”

Jane stood five feet seven in her stockings and had a fore-arm like the village blacksmith’s, but she liked being called “little one.”

“How strange that we should meet like this!” she said, blushing brightly.

“After all these years,” said Rodney Spelvin, taking a chance. It would be a nuisance if it turned out that they had met at a studio-party the day before yesterday, but something seemed to tell him that she dated back a goodish way. Besides, even if they had met the day before yesterday, he could get out of it by saying that the hours had seemed like years. For you cannot stymie these modern poets. The boys are there.

“More than five,” murmured Jane.

“Now where the deuce was I five years ago?” Rodney Spelvin asked himself.

Jane looked down at the pavement and shuffled her left shoe nervously.

“I got the violets, Rodney,” she said.

Rodney Spelvin was considerably fogged, but he came back strongly.

“That’s good!” he said. “You got the violets? That’s capital. I was wondering if you would get the violets.”

“It was like you to send them.”

Rodney blinked, but recovered himself immediately. He waved his hand with a careless gesture, indicative of restrained nobility.

“Oh, as to that——!”

“Especially as I’m afraid I treated you rather badly. But it really was for the happiness of both of us that I broke off the engagement. You do understand that, don’t you?”

A light broke upon Rodney Spelvin. He had been confident that it would if he only stalled along for awhile. Now he placed this girl. She was Jane something, the girl he had been engaged to. By Jove, yes. He knew where he was now.

“Do not let us speak of it,” he said, registering pain. It was quite easy for him to do this. All there was to it was tightening the lips and drawing up the left eyebrow. He had practised it in front of his mirror, for a fellow never knew when it might not come in useful.

“So you didn’t forget me, Rodney?”

“Forget you!”

There was a short pause.

“I read your novel,” said Jane. “I loved it.”

She blushed again, and the colour in her cheeks made her look so remarkably pretty that Rodney began to feel some of the emotions which had stirred him five years ago. He decided that this was a good thing and wanted pushing along.

“I hoped that you might,” he said in a low voice, massaging her hand. He broke off and directed into her eyes a look of such squashy sentimentality that Jane reeled where she stood. “I wrote it for you,” he added, simply.

“I hoped that you might,” he said in a low voice, massaging her hand. He broke off and directed into her eyes a look of such squashy sentimentality that Jane reeled where she stood. “I wrote it for you,” he added, simply.

Jane gasped.

“For me?”

“I supposed you would have guessed,” said Rodney. “Surely you saw the dedication?”

“The Purple Fan” had been dedicated, after Rodney Spelvin’s eminently prudent fashion, to “One Who Will Understand.” He had frequently been grateful for the happy inspiration.

“The dedication?”

“ ‘To One Who Will Understand,’ ” said Rodney, softly. “Who would that be but you?”

“Oh, Rodney!”

“And didn’t you recognize Eulalie, Jane? Surely you cannot have failed to recognize Eulalie?”

“Recognize her?”

“I drew her from you,” said Rodney Spelvin.

JANE’S mind was in a whirl as she went home in the train. To have met Rodney Spelvin again was enough in itself to stimulate into activity that hidden pulse of romance in her. To discover that she had been in his thoughts so continuously all these years and that she still held such sway over his faithful heart that he had drawn the heroine of his novel from her was simply devastating. Mechanically she got out at the right station and mechanically made her way to the cottage. She was relieved to find that William was still out on the links. She loved William devotedly, of course, but just at the moment he would have been in the way; for she wanted a quiet hour with “The Purple Fan.” It was necessary for her to re-read in the light of this new knowledge the more important of the scenes in which Eulalie French figured. She knew them practically by heart already, but nevertheless she wished to read them again. When William returned, warm and jubilant, she was so absorbed that she only just had time to slide the book under the sofa-cushion before the door opened.

Some guardian angel ought to have warned William Bates that he was selecting a bad moment for his re-entry into the home, or at least to have hinted that a preliminary wash and brush-up would be no bad thing. There had been rain in the night, causing the links to become a trifle soggy in spots, and William was one of those energetic golfers who do not spare themselves. The result was that his pleasant features were a good deal obscured by mud. An explosion-shot out of the bunker on the fourteenth had filled his hair with damp sand, and his shoes were a disgrace to any refined home. No, take him for all in all, William did not look his best. He was fine if the sort of man you admired was the brawny athlete straight from the dust of the arena; but on a woman who was picturing herself the heroine of “The Purple Fan” he was bound to jar. Most of the scenes in which Eulalie French played anything like a fat part took place either on moonlight terraces or in beautifully furnished studios beneath the light of Oriental lamps with pink silk shades, and all the men who came in contact with her—except her husband, a clodhopping brute who spent most of his time in riding-kit—were perfectly dressed and had dark, clean-cut, sensitive faces.

William, accordingly, induced in Jane something closely approximating to the heeby-jeebies.

“Hullo, old girl!” said William, affectionately. “You back? What have you been doing with yourself?”

“Oh, shopping,” said Jane, listlessly.

“See anyone you knew?”

For a moment Jane hesitated.

“Yes,” she said. “I met Rodney Spelvin.”

Jealousy and suspicion had been left entirely out of William Bates’s make-up. He did not start and frown; he did not clutch the arm of his chair; he merely threw back his head and laughed like a hyæna. And that laugh wounded Jane more than the most violent exhibition of mistrust could have done.

“Good Lord!” gurgled William, jovially. “You don’t mean to say that bird is still going around loose? I should have thought he would have been lynched years ago. Looks like negligence somewhere.”

There comes a moment in married life when every wife gazes squarely at her husband and the scales seem to fall from her eyes and she sees him as he is—one of Nature’s Class A fatheads. Fortunately for married men, these times of clear vision do not last long, or there would be few homes left unbroken. It was so that Jane gazed at William now, but unhappily her conviction that he was an out-size in rough-neck chumps did not pass. Indeed, all through that evening it deepened. That night she went to bed feeling for the first time that, when the clergyman had said “Wilt thou, Jane?” and she had replied in the affirmative, a mean trick had been played on an inexperienced girl.

AND so began that black period in the married life of Jane and William Bates, the mere recollection of which in after years was sufficient to put them right off their short game and even to affect their driving from the tee. To William, having no clue to the cause of the mysterious change in his wife, her behaviour was inexplicable. Had not her perfect robustness made such a theory absurd, he would have supposed that she was sickening for something. She golfed now intermittently, and often with positive reluctance. She was frequently listless and distrait. And there were other things about her of which he disapproved.

“I say, old girl,” he said one evening, “I know you won’t mind my mentioning it, and I don’t suppose you’re aware of it yourself, but recently you’ve developed a sort of silvery laugh. A nasty thing to have about the home. Try to switch it off, old bird, would you mind?”

Jane said nothing. The man was not worth answering. All through the pages of “The Purple Fan,” Eulalie French’s silvery laugh had been highly spoken of and greatly appreciated by one and all. It was the thing about her that the dark, clean-cut, sensitive-faced men most admired. And the view Jane took of the matter was that if William did not like it the poor fish could do the other thing.

But this brutal attack decided her to come out into the open with the grievance which had been vexing her soul for weeks past.

“William,” she said, “I want to say something. William, I am feeling stifled.”

“I’ll open the window.”

“Stifled in this beastly little village, I mean,” said Jane, impatiently. “Nobody ever does anything here except play golf and bridge, and you never meet an artist-soul from one year’s end to the other. How can I express myself? How can I be myself? How can I fulfil myself?”

“Do you want to?” asked William, somewhat out of his depth.

“Of course I want to. And I sha’n’t be happy unless we leave this ghastly place and go to live in a studio in town.”

William sucked thoughtfully at his pipe. It was a tense moment for a man who hated metropolitan life as much as he did. Nevertheless, if the solution of Jane’s recent weirdness was simply that she had got tired of the country and wanted to live in town, to the town they must go. After a first involuntary recoil, he nerved himself to the martyrdom like the fine fellow he was.

“We’ll pop off as soon as I can sell the house,” he said.

“I can’t wait as long as that. I want to go now.”

“All right,” said William, amiably. “We’ll go next week.”

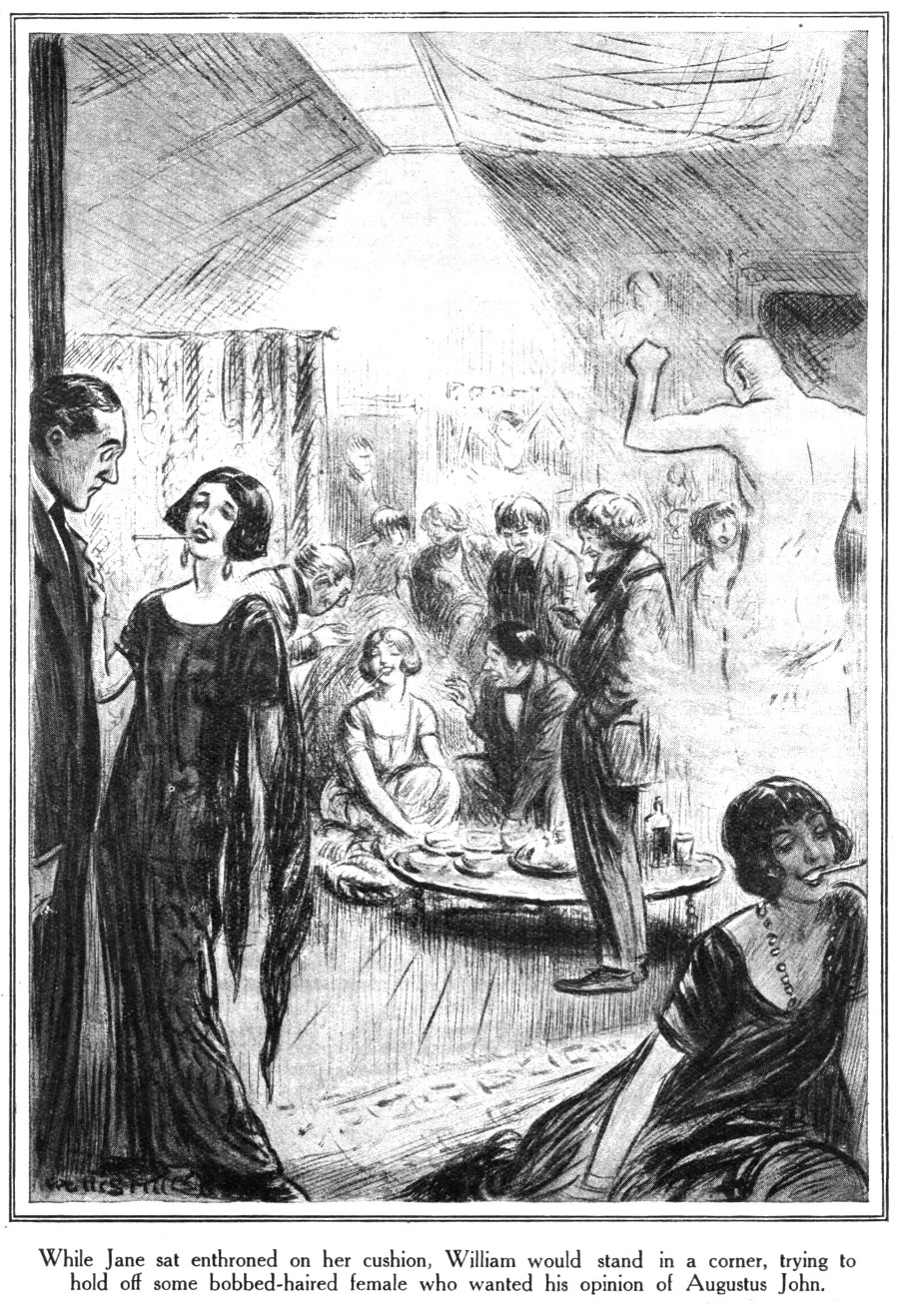

WILLIAM’S forebodings were quickly fulfilled. Before he had been in the Metropolis ten days he realized that he was up against it as he had never been up against it before. He and Jane and little Braid Vardon had established themselves in what the house-agent described as an attractive bijou studio-apartment in the heart of the artistic quarter. There was a nice bedroom for Jane, a delightful cupboard for Braid Vardon, and a cosy corner behind a Japanese screen for William. Most compact. The rest of the place consisted of a room with a large skylight, handsomely furnished with cushions and samovars, where Jane gave parties to the intelligentsia.

It was these parties that afflicted William as much as anything else. He had not realized that Jane intended to run a salon. His idea of a pleasant social evening was to have a couple of old friends in for a rubber of bridge, and the almost nightly incursion of a horde of extraordinary birds in floppy ties stunned him. He was unequal to the situation from the first. While Jane sat enthroned on her cushion, exchanging gay badinage with rising young poets and laughing that silvery laugh of hers, William would have to stand squashed in a corner, trying to hold off some bobbed-haired female who wanted his opinion of Augustus John.

The strain was frightful, and, apart from the sheer discomfort of it, he found to his consternation that it was beginning to affect his golf. Whenever he struggled out from the artistic zone now to one of the suburban courses, his jangled nerves unfitted him for decent play. Bit by bit his game left him. First he found that he could not express himself with the putter. Then he began to fail to be himself with the mashie-niblick. And when at length he discovered that he was only fulfilling himself about every fifth shot off the tee he felt that this thing must stop.

THE conscientious historian will always distinguish carefully between the events leading up to a war and the actual occurrence resulting in the outbreak of hostilities. The latter may be, and generally is, some almost trivial matter, whose only importance is that it fulfils the function of the last straw. In the case of Jane and William what caused the definite rift was Jane’s refusal to tie a can to Rodney Spelvin.

The author of “The Purple Fan” had been from the first a leading figure in Jane’s salon. Most of those who attended these functions were friends of his, introduced by him, and he had assumed almost from the beginning the demeanour of a master of the revels. William, squashed into his corner, had long gazed at the man with sullen dislike, yearning to gather him up by the slack of his trousers and heave him into outer darkness; but it is improbable that he would have overcome his native amiability sufficiently to make any active move, had it not been for the black mood caused by his rotten golf. But one evening, when, coming home after doing the Mossy Heath course in five strokes over the hundred, he found the studio congested with Rodney Spelvin and his friends, many of them playing ukaleles, he decided that flesh and blood could bear the strain no longer.

As soon as the last guest had gone he delivered his ultimatum.

“Listen, Jane,” he said. “Touching on this Spelvin bloke.”

“Well?” said Jane, coldly. She scented battle from afar.

“He gives me a pain in the neck.”

“Really?” said Jane, and laughed a silvery laugh.

“Don’t do it, old girl,” pleaded William, wincing.

“I wish you wouldn’t call me ‘old girl.’ ”

“Why not?”

“Because I don’t like it.”

“You used to like it.”

“Well, I don’t now.”

“Oh!” said William, and ruminated awhile. “Well, be that as it may,” he went on, “I want to tell you just one thing. Either you throw the bloke Spelvin out on his left ear and send for the police if he tries to get in again, or I push off. I mean it! I absolutely push off.”

There was a tense silence.

“Indeed?” said Jane at last.

“Positively push off,” repeated William, firmly. “I can stand a lot, but pie-faced Spelvin tries human endurance too high.”

“He is not pie-faced,” said Jane, warmly.

“He is pie-faced,” insisted William. “Come round to the Vienna Bon-Ton Bakery to-morrow and I will show you an individual custard-pie that might be his brother.”

“Well, I am certainly not going to be bullied into giving up an old friend just because——”

William stared.

“You mean you won’t hand him the mitten?”

“I will not.”

“Think what you are saying, Jane. You positively decline to give this false-alarm the quick exit?”

“I do.”

“Then,” said William, “all is over. I pop off.”

Jane stalked without a word into her bedroom. With a mist before his eyes William began to pack. After a few moments he tapped at her door.

“Jane.”

“Well?”

“I’m packing.”

“Indeed?”

“But I can’t find my spare mashie.”

“I don’t care.”

William returned to his packing. When it was finished, he stole to her door again. Already a faint stab of remorse was becoming blended with his just indignation.

“Jane.”

“Well?”

“I’ve packed.”

“Really?”

“And now I’m popping.”

There was silence behind the door.

“I’m popping, Jane,” said William. And in his voice, though he tried to make it cold and crisp, there was a note of wistfulness.

Through the door there came a sound. It was the sound of a silvery laugh. And as he heard it William’s face hardened. Without another word he picked up his suit-case and golf-bag, and with set jaw strode out into the night.

ONE of the things that tend to keep the home together in these days of modern unrest is the fact that exalted moods of indignation do not last. William, released from the uncongenial atmosphere of the studio, proceeded at once to plunge into an orgy of golf that for awhile precluded regret. Each day he indulged his starved soul with fifty-four holes, and each night he sat smoking in bed, pleasantly fatigued, reviewing the events of the past twelve hours with complete satisfaction. It seemed to him that he had done the good and sensible thing.

And then, slowly at first, but day by day more rapidly, his mood began to change. That delightful feeling of jolly freedom ebbed away.

It was on the morning of the tenth day that he first became definitely aware that all was not well. He had strolled out on the links after breakfast with a brassy and a dozen balls for a bit of practice, and, putting every ounce of weight and muscle into the stroke, brought off a snifter with his very first shot. Straight and true the ball sped for the distant green, and William, forgetting everything in the ecstasy of the moment, uttered a gladsome cry.

“How about that one, old girl?” he exclaimed.

And then, with a sudden sinking of the heart, he realized that he was alone.

An acute spasm of regret shot through William’s massive bosom. In that instant of clear thinking he understood that golf is not all. What shall it profit a man that he do the long hole in four, if there is no loving wife at his elbow to squeak congratulations? A dull sensation of forlorn emptiness afflicted William Bates. It passed, but it had been. And he knew it would come again.

It did. It came that same afternoon. It came next morning. Gradually it settled like a cloud on his happiness. He did his best to fight it down. He increased his day’s output to sixty-three holes, but found no relief. When he reflected that he had had the stupendous luck to be married to a girl like Jane and had chucked the thing up, he could have kicked himself round the house. He was in exactly the position of the hero of the movie when the sub-title is flashed on the screen: “Came a Day When Remorse Bit Like An Adder Into Roland Spenlow’s Soul.” Of all the chumps who had ever tripped over themselves and lost a good thing, from Adam downwards, he, he told himself, was the woollen-headedest.

On the fifteenth morning it began to rain.

NOW, William Bates was not one of your fair-weather golfers. It took more than a shower to discourage him. But this was real rain, with which not even the stoutest enthusiast could cope. It poured down all day in a solid sheet and set the seal on his melancholy. He pottered about the house, sinking deeper and deeper into the slough of despond, and was trying to derive a little faint distraction from practising putts into a tooth-glass when the afternoon post arrived.

There was only one letter. He opened it listlessly. It was from Jukes, Enderby, and Miller, florists, and what the firm wished to ascertain was whether, his deposit on white violets to be dispatched annually to Mrs. William Bates being now exhausted, he desired to renew his esteemed order. If so, on receipt of the money they would spring to the task of sending same.

William stared at the letter dully. His first impression was that Jukes, Enderby, and Miller were talking through their collective hats. White violets? What was all this drivel about white violets? Jukes was an ass. He knew nothing about white violets. Enderby was a fool. What had he got to do with white violets? Miller was a pin-head. He had never deposited any money to have white violets dispatched.

William gasped. Yes, by George, he had, though, he remembered with a sudden start. So he had, by golly! Good gosh! it all came back to him. He recalled the whole thing, by Jove! Crikey, yes!

The letter swam before William’s eyes. A wave of tenderness engulfed him. All that had passed recently between Jane and himself was forgotten—her weirdness, her wish to live in the Metropolis, her silvery laugh—everything. With one long, loving gulp, William Bates dashed a not unmanly tear from his eye and, grabbing a hat and raincoat, rushed out of the house and sprinted for the station.

AT about the hour when William flung himself into the train, Jane was sitting in her studio-apartment, pensively watching little Braid Vardon as he sported on the floor. An odd melancholy had gripped her. At first she had supposed that this was due to the rain, but now she was beginning to realize that the thing went much deeper than that. Reluctant though she was to confess it, she had to admit that what she was suffering from was a genuine soul-sadness, due entirely to the fact that she wanted William.

It was strange what a difference his going had made. William was the sort of fellow you shoved into a corner and forgot about, but when he was not there the whole scheme of things seemed to go blooey. Little by little, since his departure, she had found the fascination of her surroundings tending to wane, and the glamour of her new friends had dwindled noticeably. Unless you were in the right vein for them, Jane felt, they could be an irritating crowd. They smoked too many cigarettes and talked too much. And not far from being the worst of them, she decided, was Rodney Spelvin. It was with a sudden feeling of despair that she remembered that she had invited him to tea this afternoon and had got in a special seed-cake for the occasion. The last thing in the world that she wanted to do was to watch Rodney Spelvin eating cake.

It is a curious thing about men of the Spelvin type, how seldom they really last. They get off to a flashy start and for a while convince impressionable girls that the search for a soul-mate may be considered formally over; but in a very short while reaction always sets in. There had been a time when Jane could have sat and listened to Rodney Spelvin for hours on end. Then she began to feel that from fifteen to twenty minutes was about sufficient. And now the mere thought of having to listen to him at all was crushing her like a heavy burden.

She had got thus far in her meditations when her attention was attracted to little Braid Vardon, who was playing energetically in a corner with some object which Jane could not distinguish in the dim light.

“What have you got there, dear?” she asked.

“Wah,” said little Braid, a child of few words, proceeding with his activities.

Jane rose and walked across the room. A sudden feeling had come to her, the remorseful feeling that for some time now she had been neglecting the child. How seldom nowadays did she trouble to join in his pastimes!

“Let mother play too,” she said, gently. “What are you playing? Trains?”

“Golf.”

Jane uttered a sharp exclamation. With a keen pang she saw that what the child had got hold of was William’s spare mashie. So he had left it behind after all! Since the night of his departure it must have been lying unnoticed behind some chair or sofa.

For a moment the only sensation Jane felt was an accentuation of that desolate feeling which had been with her all day. How many a time had she stood by William and watched him foozle with this club! Inextricably associated with him it was, and her eyes filled with sudden tears. And then she was abruptly conscious of a new, a more violent emotion, something akin to panic fear. She blinked, hoping against hope that she had been mistaken. But no. When she opened her eyes and looked again she saw what she had seen before.

The child was holding the mashie all wrong.

“Braid!” gasped Jane in an agony.

All the mother-love in her was shrieking at her, reproaching her. She realized now how paltry, how greedily self-centred she had been. Thinking only of her own pleasures, how sorely she had neglected her duty as a mother! Long ere this, had she been worthy of that sacred relation, she would have been brooding over her child, teaching him at her knee the correct Vardon grip, shielding him from bad habits, seeing to it that he did not get his hands in front of the ball, putting him on the right path as regarded the slow back-swing. But, absorbed in herself, she had sacrificed him to her shallow ambitions. And now there he was, grasping the club as if it had been a spade and scooping with it like one of those twenty-four-handicap men whom the hot weather brings out on seaside links.

She shuddered to the very depths of her soul. Before her eyes there rose a vision of her son, grown to manhood, reproaching her. “If you had but taught me the facts of life when I was a child, mother,” she seemed to hear him say, “I would not now be going round in a hundred and twenty, rising to a hundred and forty in anything like a high wind.”

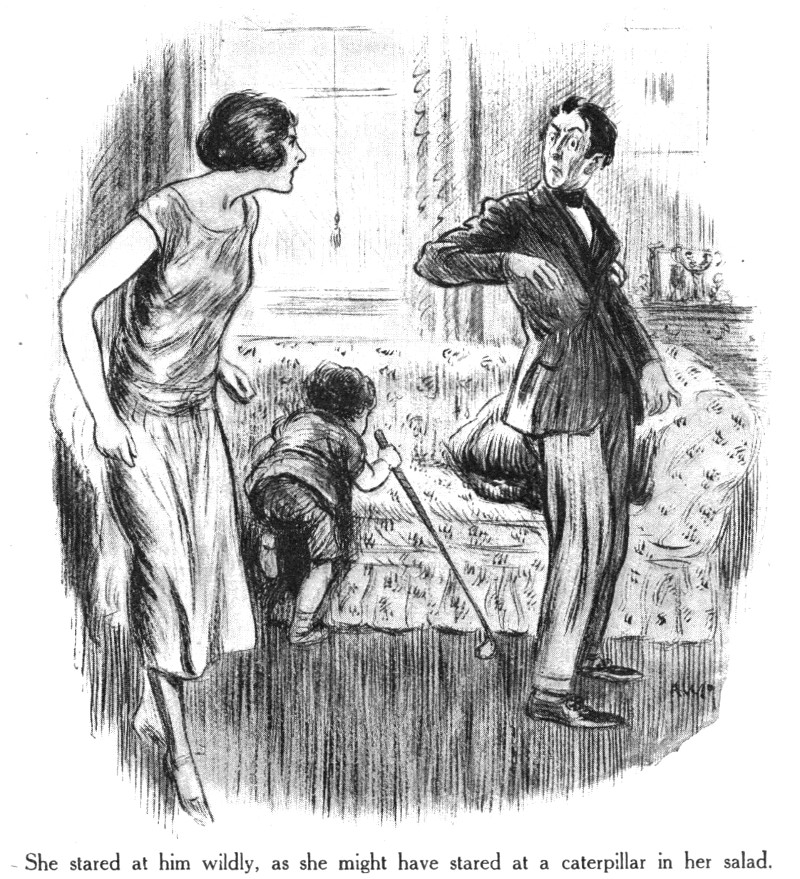

She snatched the club from his hands with a passionate cry. And at this precise moment in came Rodney Spelvin, all ready for tea.

“Ah, little one!” said Rodney Spelvin, gaily.

Something in her appearance must have startled him, for he stopped and looked at her with concern.

“Are you ill?” he asked.

Jane pulled herself together with an effort.

“No, quite well. Ha, ha!” she replied, hysterically.

She stared at him wildly, as she might have stared at a caterpillar in her salad. If it had not been for this man, she felt, she would have been with William in their snug little cottage, a happy wife. If it had not been for this man, her only child would have been laying the foundations of a correct swing under the eyes of a conscientious pro. If it had not been for this man—— She waved him distractedly to the door.

“Good-bye,” she said. “Thank you so much for calling.”

Rodney Spelvin gaped. This had been the quickest and most tealess tea-party he had ever assisted at.

“You want me to go?” he said, incredulously.

“Yes, go! go!”

Rodney Spelvin cast a wistful glance at the gate-leg table. He had had a light lunch, and the sight of the seed-cake affected him deeply. But there seemed nothing to be done. He moved reluctantly to the door.

“Well, good-bye,” he said. “Thanks for a very pleasant afternoon.”

“So glad to have seen you,” said Jane, mechanically.

The door closed. Jane returned to her thoughts. But she was not alone for long. A few minutes later there entered the female cubist painter from downstairs, a manly young woman with whom she had become fairly intimate.

“Oh, Bates, old chap!” said the cubist painter.

Jane looked up.

“Yes, Osbaldistone?”

“Just came in to borrow a cigarette. Used up all mine.”

“So have I, I’m afraid.”

“Too bad. Oh, well,” said Miss Osbaldistone, resignedly, “I suppose I’ll have to go out and get wet. I wish I had had the sense to stop Rodney Spelvin and send him. I met him on the stairs.”

“Yes, he was in here just now,” said Jane.

Miss Osbaldistone laughed in her hearty manly way.

“Good boy, Rodney,” she said, “but too smooth for my taste. A little too ready with the salve.”

“Yes?” said Jane, absently.

“Has he pulled that one on you yet about your being the original of the heroine of ‘The Purple Fan’?”

“Why, yes,” said Jane, surprised. “He did tell me that he had drawn Eulalie from me.”

Her visitor emitted another laugh that shook the samovars.

“He tells every girl he meets the same thing.”

“What?”

“Oh, yes. It’s his first move. He actually had the nerve to try to spring it on me. Mind you, I’m not saying it’s a bad stunt. Most girls like it. You’re sure you’ve no cigarettes? No? Well, how about a shot of cocaine? Out of that too? Oh, well, I’ll be going, then. Pip-pip, Bates.”

“Toodle-oo, Osbaldistone,” said Jane, dizzily. Her brain was reeling. She groped her way to the table, and in a sort of trance cut herself a slice of cake.

“Wah!” said little Braid Vardon. He toddled forward, anxious to count himself in on the share-out.

Jane gave him some cake. Having ruined his life, it was, she felt, the least she could do. In a spasm of belated maternal love she also slipped him a jam-sandwich. But how trivial and useless these things seemed now.

“Braid!” she cried, suddenly.

“What?”

“Come here.”

“Why?”

“Let mother show you how to hold that mashie.”

“What’s a mashie?”

A new gash opened in Jane’s heart. Four years old, and he didn’t know what a mashie was. And at only a slightly-advanced age Bobby Jones had been playing in the American Open Championship.

“This is a mashie,” she said, controlling her voice with difficulty.

“Why?”

“It is called a mashie.”

“What is?”

“This club.”

“Why?”

The conversation was becoming too metaphysical for Jane. She took the club from him and closed her hands over it.

“Now, look, dear,” she said, tenderly. “Watch how mother does it. She puts the fingers——”

A voice spoke, a voice that had been absent all too long from Jane’s life.

“You’ll pardon me, old girl, but you’ve got the right hand much too far over. You’ll hook for a certainty.”

In the doorway, large and dripping, stood William. Jane stared at him dumbly.

“William!” she gasped at length.

“Hullo, Jane!” said William. “Hullo, Braid! Thought I’d look in.”

There was a long silence.

“Beastly weather,” said William.

“Yes,” said Jane.

“Wet and all that,” said William.

“Yes,” said Jane.

There was another silence.

“Oh, by the way, Jane,” said William. “Knew there was something I wanted to say. You know those violets?”

“Violets?”

“White violets. You remember those white violets I’ve been sending you every year on our wedding anniversary? Well, what I mean to say, our lives are parted and all that sort of thing, but you won’t mind if I go on sending them—what? Won’t hurt you, what I’m driving at, and’ll please me, see what I mean? So, well, to put the thing in a nutshell, if you haven’t any objection, that’s that.”

Jane reeled against the gate-leg table.

“William! Was it you who sent those violets?”

“Absolutely. Who did you think it was?”

“William!” cried Jane, and flung herself into his arms.

William scooped her up gratefully. This was the sort of thing he had been wanting for weeks past. He could do with a lot of this. He wouldn’t have suggested it himself, but, seeing that she felt that way, he was all for it.

“William,” said Jane, “can you ever forgive me?”

“Oh, rather,” said William. “Like a shot. Though, I mean to say, nothing to forgive, and all that sort of thing.”

“We’ll go back right away to our dear little cottage.”

“Fine!”

“We’ll never leave it again.”

“Topping!”

“I love you,” said Jane, “more than life itself.”

“Good egg!” said William.

Jane turned with shining eyes to little Braid Vardon.

“Braid, we’re going home with daddy!”

“Where?”

“Home. To our little cottage.”

“What’s a cottage?”

“The house where we used to be before we came here.”

“What’s here?”

“This is.”

“Which?”

“Where we are now.”

“Why?”

“I’ll tell you what, old girl,” said William. “Just shove a green-baize cloth over that kid, and then start in and brew me about five pints of tea as strong and hot as you can jolly well make it. Otherwise I’m going to get the cold of a lifetime.”

(Another P. G. Wodehouse story next month.)

Notes:

Compare the American magazine version of this story from the Saturday Evening Post, October 25, 1924.

For explanations of the following golfing terms, see A Glossary of Golf Terminology on this site: brassy, bunker, driving, foozle, green, handicap, hole, hook, links, mashie, mashie-niblick, mixed foursome, niblick, pro, putter, round, short game, snifter, stroke, tee.

Wodehouse on the Niblick: Though (as is clear from the stories) Wodehouse was an avid golfer, he did not write any instructional works on the game.

The Man with the Missing Eyeball: Worldcat.org does not show a book of this name in any library. But see the notes to Mr. Mulliner Speaking for more fictive works with similar titles.

told me that one only the other day: See “Rodney Fails to Qualify” (1924).

on velvet: See Bill the Conqueror.

wam: Perhaps Wodehouse’s mishearing of the novel slang word “wham”; the earliest OED citation is from the New York Times in 1923: “Wham, a success, a knock-out.”

wind-cheater: a golf ball driven low into the wind, often with a strong backspin.

pin-splitter: an extremely accurate golf shot, figuratively splitting the flagpole which marks the location of the hole.

sponge-bag trousers: Formal morning apparel suitable for a wedding; see explanation and illustrations of these black-and-gray-striped trousers.

maddest, merriest day of all the glad new year: See the notes to A Damsel in Distress.

first crack out of the box: See the notes to The Inimitable Jeeves.

Braid Vardon Bates: Honoring famous golfers James Braid and Harry Vardon.

The Purple Fan: It is tempting to speculate that this title parodies Michael Arlen’s The Green Hat, published in June 1924 and already in its tenth printing by October of that year, a widely discussed and denounced novel considered scandalous by many. No points of internal comparison have been discovered; Arlen’s heroine Iris Storm does not have a silvery laugh, and there is no reference to white violets, for example, so the comparison is only to the grammatical form of the title, the sweeping notoriety of the book, and the celebrity of its author. Norman Murphy, in A Wodehouse Handbook, mentions having made a note of a 1920 book titled The Purple Fan by Adrian Head but being unable to find other citations for it; it is not in worldcat.org.

chesterfield: a type of overstuffed sofa with a back and upright armrests

registering pain: See the notes to Right Ho, Jeeves.

explosion-shot: A shot made in order to get out of a bunker, by striking the sand immediately behind the ball. The OED uses this sentence from Wodehouse as the first citation for the two-word term; a 1924 book is cited for “explosion” alone in this sense.

take him for all in all: See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

heeby-jeebies: Fresh slang at the time for jitters, apprehension, or alcoholic delirium; the OED’s earliest citations are American from 1923.

the scales seem to fall from her eyes: See Biblia Wodehousiana.

do the other thing: Although the oldest citations for this phrase are euphemisms for sexual activity, in Victorian and Edwardian times a less explicit colloquial sense arose, a rude dismissal somewhere between “get out of here” and “go to hell.”

Augustus John: Welsh painter, draughtsman, and etcher (1878–1961); known in the 1920s as a Post-Impressionist and a leading painter of portraits, even though some considered his depictions cruelly insightful.

tie a can to: This sentence from Wodehouse is the first OED citation for this slang phrase for dismissing or rejecting someone or something.

outer darkness: See Biblia Wodehousiana.

ukaleles: An occasional British variant of ukulele or ukelele; the UK edition of A Damsel in Distress uses that spelling, where the US version is ukulele.

hand him the mitten: See the notes to Carry On, Jeeves.

What shall it profit a man…?: See Biblia Wodehousiana.

when the sub-title is flashed on the screen: In the days of silent films, spoken lines and explanations of transitions between scenes were given in print on the screen. Most often the words were displayed over a plain dark background or still artwork, rather than being superimposed over action footage as subtitling of foreign-language films is done today; this allowed films to be easily "translated" by substituting the title inserts. They were called sub-titles because they were subsidiary to the main titles at the start of the picture, not because they appeared at the bottom of the screen. For a 1925 view of the increasing verbosity of sub-titles, see this article from Photoplay.

woollen-headedest: See Carry On, Jeeves.

slough of despond: From John Bunyan’s allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress; see the notes to Hot Water.

correct Vardon grip: See A Glossary of Golf Terminology.

a caterpillar in her salad: See the notes to The Inimitable Jeeves.

gate-leg table: See the notes to Summer Lightning

Bobby Jones: American professional golfer (1902–1971), who won his first US Open championship in 1923 at the age of 21.

green-baize cloth: See the notes to Right Ho, Jeeves.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums