Carry On, Jeeves!

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

This is part of an ongoing effort by the members of the Blandings Yahoo! Group to document references, allusions, quotations, etc. in the works of P. G. Wodehouse.

Carry On, Jeeves! was originally annotated by Mark Hodson (aka

The Efficient Baxter). The notes have been reformatted and somewhat edited and extended, but credit goes

to Mark for his original efforts, even while we bear the blame for errors of

fact or interpretation. Newly added notes are marked with * instead of the page reference to the Penguin 1999 edition. Significantly updated or expanded notes are flagged with °

Carry On, Jeeves! was originally annotated by Mark Hodson (aka

The Efficient Baxter). The notes have been reformatted and somewhat edited and extended, but credit goes

to Mark for his original efforts, even while we bear the blame for errors of

fact or interpretation. Newly added notes are marked with * instead of the page reference to the Penguin 1999 edition. Significantly updated or expanded notes are flagged with °

Carry On, Jeeves! was published in the UK in 1925, and in the US in 1927. The US edition is somewhat unusual in that it retains nearly all of the British spelling choices such as “colour” and “realise.” Some of the stories (marked * in the list below) were reworked from the collection My Man Jeeves, published in the UK in 1919, one featuring a young man called Reggie Pepper, a prototype of Bertie, as well as stories about Bertie Wooster and Jeeves. Parenthesized dates are initial magazine appearances.

|

Jeeves Takes Charge (1916) The Artistic Career of Corky* (revised from “Leave It to Jeeves”, 1916) Jeeves and the Unbidden Guest* (1916–17) Jeeves and the Hard-Boiled Egg* (1917) The Aunt and the Sluggard* (1916) The Rummy Affair of Old Biffy (1924) Without the Option (1925) Fixing It for Freddie* (revised from the Reggie Pepper story “Helping Freddie”, 1911–12) Clustering Round Young Bingo (1925) Bertie Changes His Mind (1922) |

Jeeves Takes Charge (pp. 1–26)

This story was originally published in 1916, and is in the fictional chronology the earliest of the Jeeves stories. It was published in amended form in Carry On, Jeeves! (1925 in UK, 1927 in US). Page references are to the 1999 Penguin edition of Carry On, Jeeves, in which the story runs from pp. 1–26.

Easeby (p. 1)

Fictitious, but does occur as an occasional variant spelling of Easby, a village near Richmond, North Yorks. Many of Wodehouse’s country houses are placed in Shropshire. Placenames ending in ‘-by’ are normally of Danish origin, and would be very unusual in Shropshire, though common in Northeast England.

hand ... the mitten (p. 1)

registry office (p. 1)

Employment agency for domestic servants.

Types of Ethical Theory (p. 2)

MARTINEAU, James. Types of Ethical Theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1885 (2 vols). Not to be confused with Broad, C. D. FIVE TYPES OF ETHICAL THEORY, which was only published in 1934, but is still in print.

The first quotation can be seen in context at Google Books. “Idiopsychological Ethics” is the title of Book I of Volume II. The later quotation, near the end of this story, can be seen here.

healing zephyr (p. 2)

The zephyr is a west wind, or gentle breeze.

Worcester Sauce (p. 3)

A proprietary condiment, made commercially and sold as Worcestershire Sauce in the UK since 1838 by Lea and Perrins to a recipe brought back from Bengal by Lord Marcus Sandys. [Note that the original appearances of this story in both British and American magazines referred simply to “dark meat-sauce” here. —KS/NM March 2016] (Thanks to Jim Munn for reminding us of the difference between the real-life trade name and Jeeves’s abbreviated reference to it. 2021-07-24)

Lord Worplesdon (p. 3)

Worplesdon is a village about 5 miles north of Guildford, Surrey (where PGW was born). Lord Worplesdon is clearly an hereditary peer, as his daughter is referred to as Lady Florence. However, when he recovers from his breakdown to reappear in Joy in the Morning, he seems to have become a shipping tycoon.

Iron hand (or fist) in the velvet glove (p. 5)

ruthlessness, tyranny, masked by a polite and courteous manner. Ascribed to Napoleon, as in Thomas Carlyle’s “Model Prisons” (1850) in Latter-day Pamphlets.

give them a what’s-its-name, they take a thingummy (p. 5)

Give an inch, they take a mile – i.e. allow any liberty and they will take advantage of it. “What’s-its-name” and “thingummy” are two of the many colloquialisms Bertie employs when unable to recall the correct words.

wild oats (p. 7)

avena fatua, a weed found in cornfields. Used metaphorically, sowing one’s wild oats is to indulge youthful folly, knowing that it will later be overwhelmed by the genuine corn. In Danish, “Loki’s wild oats” are spring mists which appear just before the crops start to sprout. (Brewer)

rounder (p. 7)

A dissolute person, someone who does the rounds of bars, etc. The OED lists this as 19th century American slang – presumably Bertie picked up the expression in New York.

(In at least some editions the more common term “bounder” is used here.)

Oakshott (p. 7)

Oakshott is another Hampshire place name, a village just north of Petersfield.

bantam weight *

A weight class of boxers recognized since 1894; current upper limit is 118 pounds, lighter than lightweights and featherweights. These smaller boxers would be agile, hence the comparison here to Florence’s side-stepping.dependent on Uncle Willoughby *

The inference is that Bertie’s uncle is trustee of his inheritance until he reaches a specified age, most likely 25. Internal evidence of the cigar reminicence suggests that he is 24 at the time of this story.tabasco (p. 8)

A proprietary hot sauce made with chili peppers. Tabasco® brand products are produced by McIlhenny Company, founded in 1868 at Avery Island, Louisiana. Bertie is implying that Uncle Willoughby was hot stuff in his younger days.

a quart and a half (p. 8)

Approximately 1.7 litres, assuming that this is 1.5 British imperial quarts rather than US quarts.

Lord Emsworth (p. 8)

Our Lord Emsworth, Clarence, the ninth Earl, first appeared in Something New/Something Fresh (1915). A previous holder of the title was mentioned in “The Matrimonial Sweepstakes” (1910). Emsworth’s brother, Gally, seems to share many of Uncle Willoughby’s attributes, and his equally lively memoirs provide the plot for Summer Lightning (1929) and Heavy Weather (1933)

Rosherville Gardens (p. 8)

Victorian pleasure gardens at Gravesend on the Thames Estuary. The site is now partly occupied by a GEC factory.

Lady Carnaby’s Memories of Eighty Interesting Years (p. 9)

Carnaby is a village in the East Riding of Yorkshire (now Humberside), near Bridlington.

Compare Lady Bablockhythe’s Frank Recollections of a Long Life (“Clustering Round Young Bingo”) and Lady Wensleydale’s memoirs (referred to by Lord Tilbury in Chapter 1 of Heavy Weather as Sixty Years Near the Knuckle in Mayfair).

Norman Murphy suggests in The Reminiscences of Galahad Threepwood that the original for Lady Carnaby/Wensleydale/Bablockhythe is Adeline de Horsey, countess of Cardigan and Lancastre. She was for many years the mistress of Lord Cardigan of the Charge of the Light Brigade, marrying him after the death of his first wife. After his death, she married the Portugese Comte de Lancastre. Her book My Recollections appeared in 1909.

spineless invertebrate (p. 10)

As a budding novelist, one might have expected Florence to avoid such tautologies, even if she is quoting Aunt Agatha.

in the night watches (p. 12)

When I remember thee upon my bed, and meditate on thee in the night watches.

Psalm 63:6

Mine eyes prevent the night watches, that I might meditate in thy word.

Psalm 119:148

By analogy to nautical terminology, the King James Bible uses the word “watches” to represent what for the psalmists were simply measures of time – they considered the night as subdivided into four parts.

eftsoons or right speedily (p13)

eftsoons (obsolete) soon afterwards, forthwith. Commonly used to give an archaic effect, even a century before Wodehouse:

He holds him with his skinny hand,

“There was a ship,” quoth he.

“Hold off! unhand me, grey-beard loon!”

Eftsoons his hand dropt he.

[Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798)]

Eugene Aram (p. 14)

The English philologist Eugene Aram (1704–59) was a self-taught expert on the Celtic languages. Before he could complete his Anglo-Celtic dictionary, he was tried and executed for the murder of his friend Daniel Clarke. As well as Thomas Hood’s poem, which Bertie attempts to quote, there is a novel by Bulwer Lytton on the subject. Hood’s poem was effectively sabotaged by Lewis Carroll’s parody “The Walrus and the Carpenter.”

Bertie has got the metre and the storyline right, but there is no line in the poem that starts “I slew him....” Elsewhere, Bertie often quotes the final stanza:

That very night while gentle sleep

The urchin’s eyelids kissed,

Two stern-faced men set out from Lynn,

Through the cold and heavy mist;

And Eugene Aram walked between,

With gyves upon his wrist.

[Thomas Hood “The Dream of Eugene Aram” (1829)]

falling dew (p. 17)

A frequent idea in poetry, so Bertie may not have a specific quotation in mind (among other places, the phrase also occurs in Wilde’s Endymion and at least two poems by “A.E.”):

Whither, midst falling dew,

While glow the heavens with the last steps of day,

Far, through their rosy depths, dost thou persue

Thy solitary way?

[“To a Waterfowl” by William Cullen Bryant (1815)]

Raffles (p. 19)

The gentleman burglar, created by Conan Doyle’s brother-in-law E. W. Hornung, first appeared in 1899.

two-year-old *

The age when a thoroughbred racehorse usually begins training and sometimes participating in races against other young horses; a time of great liveliness and vigor.

Walkinshaw’s Supreme Ointment (p. 23)

In Something Fresh, Ch 5 pt 5 (1915), James the footman is criticised for getting Above Himself after appearing in an advertisement for this same ointment.

Nietzsche (p. 24)

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), German philosopher of a realist persuasion, often considered one of the first of the existentialists. He had a considerable influence on artists, writers and thinkers in Continental Europe but was less influential in English-speaking countries, as reflected in Jeeves’ judgement on him.

frost *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

The Artistic Career of Corky (pp. 27–45)

This story was originally published as “Leave It to Jeeves” in the Saturday Evening Post in 1916, and appeared under this title in My Man Jeeves (1919). It was published in amended form in Carry On, Jeeves! (1925 in UK, 1927 in US). Page references are to the 1999 Penguin edition of Carry On, Jeeves, in which the story runs from pp. 27–45.

Extensive additional annotations to this story appear as end notes to the Saturday Evening Post transcription, here on Madame Eulalie.

jute (p. 35) °

Jute is a natural fibre, extensively grown in India, and most commonly used to make sacks. Dundee used to be a major centre of the British jute industry. Besides Alexander Worple in the present story, there are a few other jute businessmen in Wodehouse:

• Mr. Arthur Puckey, father of a student at Harrow House in “Out of School” (US version, 1909)

• Bradbury Fisher has large interests in jute as well as other commodities in “Keeping In with Vosper” (1926; in The Heart of a Goof, 1926/27)

• Sir Edward Deeping, deeply immersed in the jute industry in “Ukridge and the Old Stepper” (1928)

• Berry Conway’s late great-uncle, a Mr. Jervis, in Big Money (1931)

the sweet-toned, carelessly-flowing warble of the purple finch linnet *

John Dawson shares this discovery, sent to him by a fellow Wodehouse scholar:

Although the Purple Finch often essays to sing in the autumn and earliest spring, its full powers of voice belong alone to the nuptial season. Then it easily takes its place among our noteworthy song birds. Its full song is a sweet-toned, carelessly flowing warble…

From the article on the Purple Finch (Carpodacus purpureus) by Eugene P. Bicknell, in Frank W. Chapman’s Handbook of Birds of Eastern North America, p. 282 (third edition, 1896).

milk of human kindness (p. 35)

Yet do I fear thy nature;

It is too full o’ the milk of human kindness.

[Shakespeare, Macbeth. Act i. Sc. 5.]

miss-in-baulk (p. 37)

In billiards, it is not permitted to hit a ball in the baulk area of the table in certain circumstances.

Sargent (p. 41)

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925). American painter, closely associated with the French impressionists, and chiefly famous for his portraits.

Baby Blobbs (p. 44)

There are a number of other stories in which portraits find unexpected uses. Brancepeth Mulliner in “Buried Treasure” (Lord Emsworth and Others) gets the idea for a comic fish while painting Lord Bromborough’s portrait; In Quick Service, Mrs Chavender’s portrait is used to advertise Duff and Trotter hams.

Jeeves and the Unbidden Guest (pp. 46–68)

This story was originally published in 1916, and appeared in book form in My Man Jeeves (1919).

It was published in amended form in Carry On, Jeeves! (1925 in UK, 1927 in US). Page references are to the 1999 Penguin edition of Carry On, Jeeves, in which the story runs from pp. 46–68.

Shakespeare (p. 46)

This reference is so vague it’s probably impossible to pin down an exact source. Bertie seems to be talking about the concept of Nemesis, which is one of the leading elements of Greek tragedy. The original SEP appearance of the story used the spelling “Shakspere.”

President Coolidge (p. 47)

Vice-President Calvin Coolidge (1872–1933) became 30th President of the United States in 1923 on the death of Warren Harding. Clearly, this was a detail added in the revision of the story for publication in Carry On, Jeeves. Coolidge was famous for his taciturnity and his capacity for “effectively doing nothing,” which made him very popular.

In the story’s initial appearance Jeeves recommends “the Longacre—as worn by John Drew” [pictured at right] while Bertie buys the Country Gentleman, as worn by Jerome D. Kern (Wodehouse’s friend and theatrical collaborator).

In the story’s initial appearance Jeeves recommends “the Longacre—as worn by John Drew” [pictured at right] while Bertie buys the Country Gentleman, as worn by Jerome D. Kern (Wodehouse’s friend and theatrical collaborator).

What ho! without there? (p. 47)

Seems to have become a cliché of historical fiction, cf. for examples Gilbert and Sullivan’s Utopia Limited, Edgar Rice Burroughs The Outlaw of Torn and Scott’s Kenilworth. The earliest I found was a play by George Lillo (1693–1739), The London Merchant (1731), but it certainly must go back further.

Lady Malvern ... Lord Pershore (p. 47)

Both titles are taken from Worcestershire placenames. Lord Pershore’s is presumably a courtesy title as eldest son, so Lady Malvern’s husband must still be alive.

Durbar (p. 48)

(Urdu) A public reception or levee, usually held with much pomp and ceremony to mark the accession of a ruler to power. The term was adopted by the British when Queen Victoria had herself proclaimed Empress of India at the Delhi Durbar of 1877. Lord Curzon, as Viceroy, stage-managed an even more spectacular Durbar in 1903 to mark the accession of Edward VII, and the last was held for George V in December 1911. It is presumably this one which Lady Malvern attended.

OP to Prompt Side (p. 49)

Right to left, if speaking as an actor; left to right, if speaking as a member of the audience. In a British theatre, the prompter usually sits in the wings of the stage, to the actors’ left. Thus Prompt Side is left and Off Prompt right as seen by the performers.

on the Halls (p. 49)

Music halls or Vaudevilles were theatres specialising in variety entertainment, and usually also serving food and drink to a mainly lower-class public. They were thus a considerable step down in respectability even from the “legitimate theatre,” and Aunt Agatha would not have been at all pleased.

the rest of my natural (p. 50) °

Shortened from “...for the rest of his natural life” – Conventional phrase used to pronounce a sentence of life imprisonment or exile, and in other legal contexts dealing with a person’s full biological lifespan. (The contrasting concept of “civil death” — losing one’s place in society due to treason or felony — is a fine point in Blackstone’s Commentaries on the law.)

Guy Bud writes to remind us that a life prison sentence was not known as such in England at this time, having been instituted when capital punishment was discontinued in 1965; prior to that, indefinite prison sentences were “detention at His/Her Majesty’s Pleasure.” On the other hand, sentencing for “the rest [or term] of his natural life” was used in the United States, Australia, and New Zealand when this story was written. Bertie could have picked up the term from an American crime thriller, for instance, or from American newspapers while he was in New York.

Similar phrasing has other legal usages in wills, trusts, conveyances of property, and so forth in giving someone a life interest in property or in the income from an estate. Most of the online search returns found so far refer to the “remainder of her natural life” (typically for widows or other female survivors, at that era thought to need trustees to control their inheritance).

Sing-Sing (p. 51)

The state penitentiary at Ossining, New York. Mentioned frequently in Wodehouse.

‘India and the Indians’ … less than a month *

Wodehouse often satirized the sort of author who purports to be an expert on an entire country and its people after a brief visit. Here we have both Lady Malvern, proposing to detail America after less than a month as she did for India, and her friend Sir Roger Cremorne, who stayed only two weeks in the USA. An unnamed baronet in The Intrusions of Jimmy/A Gentleman of Leisure, ch. 25 (1910), has written Modern America and Its People after a stay of only two weeks in New York. Lord Wildersham has done the same in “The Fatal Kink in Algernon” (1916). There may well be others.

A possible literary source is The Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens, in which “the famous foreigner, Count Smorltork” is “gathering materials for his great work on England“—indeed he claims “they are gathered” after a “ver long time—fortnight—more” in England. [NM]

stuffed eelskin (pp. 52–3)

Where is my wandering boy tonight (p. 54)

Where is my wandering boy tonight

The boy of my tenderest care

The boy that was once my joy and light

The child of my love and prayer

Where is my boy tonight

Where is my boy tonight

My heart o’erflows, for I love him, he knows

O where is my boy tonight

Once he was pure as morning dew

As he knelt at his mother’s knee

No face was so bright, no heart more true

And none was so sweet as he

O chould I see you now my boy

As fair as in olden time

When prattle and smile made home a joy

And life was a merry chime

Go for my wand’ring boy tonight

Go search for him where you will

But bring him to me with all his blight

And tell him I love him still

Popular ballad, words and music by the Reverend Robert Lowry, 1877.

Also the title of a 1922 film starring Cullen Landis as a young man who leaves home and sweetheart and becomes involved with a cynical chorus girl.

Young man, rejoice in thy youth (p. 56)

Rejoice, O young man, in thy youth; and let thy heart cheer thee in the days of thy youth, and walk in the ways of thine heart, and in the sight of thine eyes: but know thou, that for all these things God will bring thee into judgment

[(Ecclesiastes 11:9).]

Motty seems to have forgotten the second part!

Much Middleford (p. 56)

Fictitious town, cf. the real placename Much Wenlock. Motty would have been a neighbour of Ashe Marson, hero of Something Fresh/Something New (1915).

The Old Oaken Bucket (p. 59)

How dear to my heart are the scenes of my childhood

When fond recollection presents them to view

The orchard, the meadow, the deep tangled wildwood,

And ev’ry loved spot which my infancy knew

The wide spreading pond, and the mill that stood by it,

The bridge and the rock where the cataract fell;

The cot of my father, the dairy house nigh it,

And e’en the rude bucket that hung in the well.

The old oaken bucket, the iron bound bucket,

The moss covered bucket that hung in the well.

The moss covered bucket I hailed as a treasure,

For often at noon, when returned from the field,

I found it the source of an exquisite pleasure,

The purest and sweetest that nature can yield.

How ardent I seized it, with hands that were glowing,

And quick to the white pebbled bottom it fell

Then soon, with the emblem of turth overflowing,

And dripping with coolness, it rose from the well.

The old oaken bucket, the iron bound bucket,

The moss covered bucket that hung in the well.

[Song, words by Samuel Woodworth (1818), usually sung to a tune by George Kiallmark (1870)]

Daniel and the lions’ den (p. 59)

See Daniel, Chapter 6.

16 Then the king commanded, and they brought Daniel, and cast him

into the den of lions. Now the king spake and said unto Daniel, Thy God

whom thou servest continually, he will deliver thee.

17 And a stone was brought, and laid upon the mouth of the den; and

the king sealed it with his own signet, and with the signet of his lords;

that the purpose might not be changed concerning Daniel.

18 Then the king went to his palace, and passed the night fasting:

neither were instruments of music brought before him: and his sleep went

from him.

19 Then the king arose very early in the morning, and went

in haste unto the den of lions.

20 And when he came to the den, he cried with a lamentable voice unto

Daniel: and the king spake and said to Daniel, O Daniel, servant of the

living God, is thy God, whom thou servest continually, able to deliver thee

from the lions?

21 Then said Daniel unto the king, O king, live for ever.

22 My God hath sent his angel, and hath shut the lions’ mouths, that

they have not hurt me: forasmuch as before him innocency was found in me;

and also before thee, O king, have I done no hurt.

23 Then was the king exceeding glad for him, and commanded that they

should take Daniel up out of the den. So Daniel was taken up out of the

den, and no manner of hurt was found upon him, because he believed in his

God.

24 And the king commanded, and they brought those men which had accused

Daniel, and they cast them into the den of lions, them, their children,

and their wives; and the lions had the mastery of them, and brake all their

bones in pieces or ever they came at the bottom of the den.

Rocky Todd (p. 60)

See The Aunt and the Sluggard.

Long Island (p. 60)

Wodehouse had rented a house in Bellport, Long Island in 1914.

Blackwell’s Island (p. 64)

A prison was established by New York City on this island in the East River in 1832, soon joined by a workhouse, lunatic asylum and hospital. The prison closed in 1930 and inmates were moved to Rikers Island.

Jeeves and the Hard-Boiled Egg (pp. 69–90)

This story was originally published in The Saturday Evening Post and in the Strand Magazine in March and August respectively in 1917. The story first appeared in book format in 1919 in My Man Jeeves. It was published in amended form in Carry On, Jeeves! (1925 in UK, 1927 in US). Page references are to the 1999 Penguin edition of Carry On, Jeeves, in which the story runs from pp. 69–90.

moustache (p. 70)

Wodehouse is so consistently against facial hair in his fiction, that we must assume this to be a personal prejudice of his. Bertie also grows a moustache in Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit (1954), where it proves to have the disadvantage of making him irresistible to Florence Craye. The most famous moustache story is of course “Buried Treasure” in Lord Emsworth and Others.

Grant’s Tomb (p. 70)

Ulysses S. Grant (1822—85), commander in chief of the Union army in the Civil War and 18th President (1869—77) of the United States. The remains of Grant and his wife lie in an elegant classical building in New York City which used to attract more visitors than the Statue of Liberty. The building is owned by the US National Park Service.

Lord Bridgnorth (p. 78)

Bridgnorth is a town in Shropshire.

chicken farm (p. 78)

Wodehouse’s first successful “adult” novel was Love Among the Chickens (1906), based on the experiences of Carrington Craxton, an acquaintance of Bill Townend who attempted to run a chicken farm.

doubloons and pieces of eight (p. 79)

Two types of archaic Spanish coins, often mentioned in connection with Caribbean pirates – remember Captain Flint’s parrot in Stevenson’s Treasure Island saying “Pieces of eight, pieces of eight.” Doubloon comes from Spanish doblón, and the piece of eight was worth eight reals.

Boost for Birdsburg (p. 82)

A similar deputation of boosting businessmen appears in Sinclair Lewis’s Babbitt (1922). There does not appear to be a real place of this name in the USA, although there is one in South Africa. Apparently Beattystown, New Jersey narrowly missed being called Birdsburg. The phrase “Boost for Birdsburg” has taken on a life of its own as an expression of American provincialism.

quid ... o’goblins (pp. 88,89)

Slang expressions for English pounds sterling. “Quid” is still current, and its origins are obscure; the obsolete “o’goblin” is a short variant of “Jimmy O’Goblin,” rhyming slang for “sovereign” (also obsolete).

The Aunt and the Sluggard (pp. 91–120)

This story was originally published in 1916. The story first appeared in book format in 1919 in My Man Jeeves. It was published in amended form in Carry On, Jeeves! (1925 in UK, 1927 in US). Page references are to the 1999 Penguin edition of Carry On, Jeeves, in which the story runs from pp. 91–120.

The Aunt and the Sluggard (p. 91)

6 Go to the ant, thou sluggard; consider her ways, and be wise:

7 which having no guide, overseer, or ruler,

8 provideth her meat in the summer, and gathereth her food in the harvest.

[Proverbs, 6, 6–8]

Jeeves … a guide, don’t you know; philosopher, if I remember rightly, and—I rather fancy—friend. (magazine versions only) *

When statesmen, heroes, kings, in dust repose,

Whose sons shall blush their fathers were thy foes,

Shall then this verse to future age pretend

Thou wert my guide, philosopher, and friend!

(1688–1744): An Essay on Man, Epistle IV.

the strenuous life (p. 92)

[Added 2015-12-08 NM:] “The Strenuous Life” is the title of an 1899 speech by Theodore Roosevelt, and of a 1900 book containing it along with other essays. The speech opens: “I wish to preach, not the doctrine of ignoble ease, but the doctrine of the strenuous life, the life of toil and effort, of labor and strife. . . .”

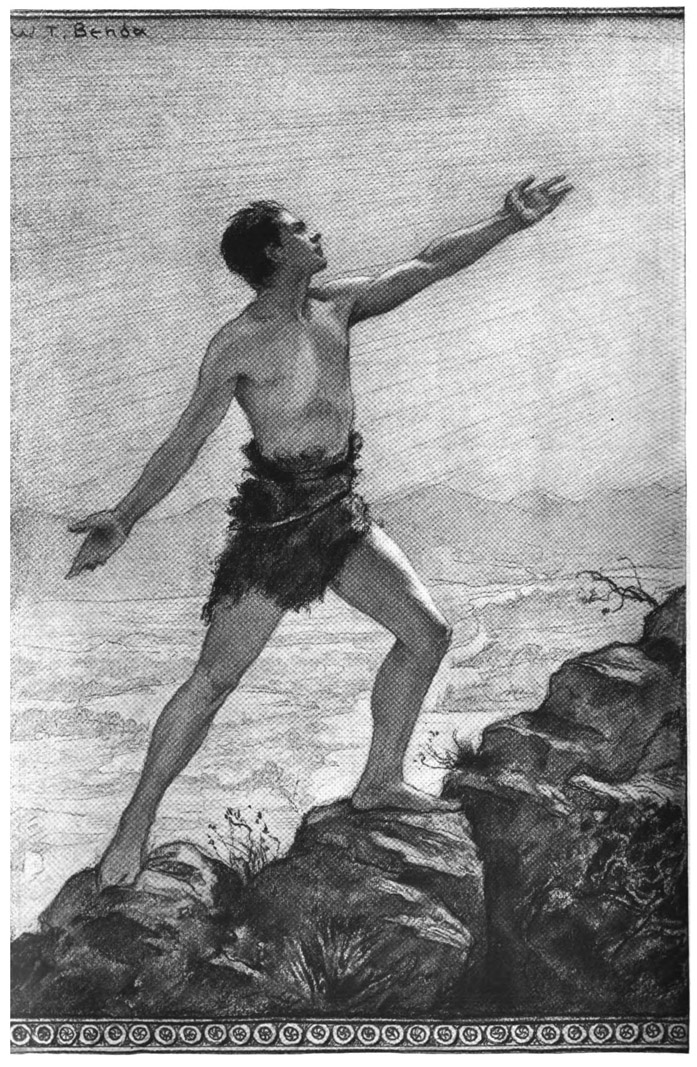

Be! (p. 92)

Wodehouse loved to parody modern verse, but here he is presumably having a go at Walt Whitman (1819–92) and his imitators. The “fairly nude chappie with bulging muscles” would seem to confirm this idea. [The image below is from Cosmopolitan, July 1920, illustrating Edgar A. Guest’s poem “Youth”; this is later than the original appearance of this story, so cannot be the specific picture Wodehouse had in mind, but it is close enough in spirit that I cannot refrain from including it here. —NM]

[Added 2015-12-08:] Dirk Laurie suggests that a more specific source is Longfellow’s A Psalm of Life (see annotations to The Girl on the Boat, p. 134, for the poem in full). The poem contains these lines, contiguously:

Be not like dumb, driven cattle!

Be a hero in the strife!

Trust no Future, howe’er pleasant!

Let the dead Past bury its dead!

Act—act in the living Present!

Compare with the first few lines of the parody:

Be!

Be!

The past is dead.

To-morrow is not born.

Be to-day!

To-day!

My heart’s in the Highlands, my heart is not here (p. 95)

Farewell to the Highlands, farewell to the North,

The birth-place of Valour, the country of Worth;

Wherever I wander, wherever I rove,

The hills of the Highlands for ever I love.

Chorus.—My heart’s in the Highlands, my heart is not here,

My heart’s in the Highlands, a-chasing the deer;

Chasing the wild-deer, and following the roe,

My heart’s in the Highlands, wherever I go.

Farewell to the mountains, high-cover’d with snow,

Farewell to the straths and green vallies below;

Farewell to the forests and wild-hanging woods,

Farewell to the torrents and loud-pouring floods.

My heart’s in the Highlands, &c.

[Robert Burns (1759–96) “Farewell to the Highlands” (1790)]

Jimmy Mundy (p. 96)

Based on Billy Sunday (1862–1935). Sunday was a successful baseball player with the Chicago White Stockings and the Pittsburgh Pirates before becoming a full-time evangelist in 1897. In 1917 he held his famous 10 week Campaign for New York in which over 98000 people were reported to have been converted. Wodehouse mentions Sunday in a review he wrote for Vanity Fair in March 1915 under the heading “Boy! Page Mr. Comstock!” (see Phelps, chapter 9).

hit-the-trail campaign *

Billy Sunday (see above) coined the phrase “hit the sawdust trail” to describe the act of coming to the front of a revival meeting to accept the evangelist’s invitation to be converted to Christianity. The phrase was often shortened to “hit the trail.”

Madison Square Garden (p. 96)

The first Madison Square Garden arena was built by Phineas T. Barnum on the site of a former railway yard in 1874. In 1890, this was replaced by a vast building in the Moorish style, which could hold as many as 17,000 people, and survived until 1924.

Gehenna (p. 96)

New Testament name for hell, deriving from the Vale of Hinnom, a valley south of Jerusalem. Occurs eight times in the NT (Matt. v. 22, 29, x. 28, xiii. 15, xviii. 9, xxiii. 15, 33; James iii. 6); the word Hades (which Rocky uses on p 110) is slightly more popular, appearing nine times. (source: Brewer)

Georgie Cohan (p. 101)

George M. Cohan (1878–1942), American actor, singer, songwriter, playwright and producer. His most famous composition was the song “Over There” (1919). There is an anecdote about him in Bring On the Girls.

Willie Collier (p. 101)

Broadway comic actor and producer.

Fred Stone (p. 101)

Broadway actor, later moved to Hollywood. Famously played the role of the Tin Man in a 1903 Broadway production of The Wizard of Oz.

Doug. Fairbanks (p. 101) °

Douglas Fairbanks Sr., American actor, became one of the first big stars of Hollywood after he moved there in 1915. Starred in many famous swashbuckling adventure films of the silent era. Married to Mary Pickford. In a letter in Performing Flea dated 1931, Wodehouse mentions dining with them.

In 1911, Fairbanks played the title role in a stage adaptation of A Gentleman of Leisure, adapted by John Stapleton and Wodehouse from Wodehouse’s novel (also known as The Intrusion of Jimmy). Beginning in 1921, the Herbert Jenkins reissues of A Gentleman of Leisure were dedicated to Fairbanks.

Ed Wynn (p. 101)

Vaudeville comedian, worked with the Ziegfeld Follies from 1914, but was blacklisted for a while after organising an actors’ strike in 1919. Later worked in film, radio and television.

Laurette Taylor (p. 101)

Broadway star, appeared in the film "Peg o’ My Heart” (1922).

St. Aurea (p. 107)

An 8th century abbess of Rouen (feastday 6 October). There doesn’t appear to be a hotel of that name in New York at present.

David Belasco (p. 114)

(1859–1931) Playwright, producer and manager. Known as “the Bishop of Broadway.” Well-known works include: The Girl I Left Behind Me (1893), Heart of Maryland (1895), Zaza (1899), and Madame Butterfly (1900).

Jim Corbett (p. 114)

“Gentleman Jim” Corbett (1866–1933): American boxer, heavyweight champion from 1892 (defeating John L. Sullivan) to 1897 (defeated by Bob Fitzsimmons).

The Rummy Affair of Old Biffy (pp. 121–147)

This story was originally published in 1924. The story first appeared in book format in Carry On, Jeeves! (1925 in UK, 1927 in US). Page references are to the 1999 Penguin edition of Carry On, Jeeves, in which the story runs from pp. 121–147.

espièglerie (p. 121)

(French) mischievousness, impishness, roguishness. A favourite word of Bertie’s. Cf. the legendary German prankster Till Eulenspiegel.

joie de vivre (p. 121)

(French) exuberance, healthy enjoyment of life.

Bohemian revels (p. 121)

The association of the word “Bohemian” with impecunious young Parisian writers and artists was popularised by Henri Murger’s novel Scènes de la vie de Bohème (1847–9) and Puccini’s opera based on it (1896).

the other side of the river (p. 121)

The implication is that Bertie’s hotel is on the respectable right bank of the Seine. Artists would – of course – live on the left bank.

the quiet evenfall (p. 121)

Alas for her that met me,

That heard me softly call,

Came glimmering thro’ the laurels

At the quiet evenfall,

In the garden by the turrets

Of the old manorial hall.

[Tennyson, Maud, II 215–220 (1855) ]

lads about town *

See Thank You, Jeeves.

gaiters *

Protective leggings covering the top of the shoe and the lower leg, almost to the knee. Worn by horsemen and farmers as well as being part of a bishop’s costume: see Meet Mr. Mulliner.

Hotel Avenida, Rue du Colisée (p. 122)

The Rue du Colisée is a side street of the Ave. des Champs-Élysées in central Paris. There is currently no Hotel Avenida listed in Paris.

mes gants... (p. 122)

(French) “My gloves, my hat, sir’s walking stick.”

whangee is not a French word, of course, but an English term, current

in the late 18th century, deriving from huang, the Chinese word for

the type of bamboo used for making walking sticks.

Sorbonne (p. 122)

University, on the left bank, quite some way from Biffy’s hotel.

woollen-headed *

The OED has an entry for woollen-head as a noun for a dull person (cited from 1756) and two 1883 citations for woolly-headed meaning dull-witted, but no entry or citation for the specific form Wodehouse frequently used as an adjective for someone forgetful or fuzzy-thinking, as in the examples here. Some American magazine editors changed the spelling to woolen-headed.

See also cloth-headed in Money in the Bank.

“You’re infernally late. I suppose, in your woollen-headed way, you forgot all about it.”

“Pots o’ Money” (1911; in The Man Upstairs, 1914)

Another man might have waited to make certain that his message had reached its destination, but not woollen-headed Wheeler, the most casual individual in New York.

“Strange Experiences of an Artist’s Model” (1921; in Indiscretions of Archie, 1921)

It was just the sort of woollen-headed thing fellows did, forgetting facts like that.

Three Men and a Maid, ch. 16.3 / The Girl on the Boat, ch. 17.4 (book versions only, 1922)

“Have you ever in your life heard of such a footling, idiotic, woollen-headed proceeding?”

“The Return of Battling Billson” (1923; in Ukridge, 1924)

In Frederick’s cold grey eye as he looked over his shoulder and backed the car there was only the weary scorn of a superman for the never-ending follies of a woollen-headed proletariat.

“No Wedding Bells for Him” (1923; in Ukridge, 1924)

And then it suddenly came to me that Ukridge in his woollen-headed way had omitted to mention the name of a single one of this woman’s books.

“First Aid for Dora” (1923; in Ukridge, 1924)

“Then why, you poor woollen-headed fish,” bellowed Ukridge, exploding, “why on earth didn’t you stop him?”

“The Exit of Battling Billson” (1924; in Ukridge, 1924)

Of all the chumps who had ever tripped over themselves and lost a good thing, from Adam downwards, he, he told himself, was the woollen-headedest.

“Jane Gets Off the Fairway” (1924; in The Heart of a Goof, 1926)

He had always in his woollen-headed way been very fond of his niece Angela, and it was nice to think that the child had such solid good sense and so much cool discernment.

Lord Emsworth in “Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey!” (1927; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

“I suppose what you’re trying to break to me in your rambling, woollen-headed way is that Johnnie is mooning round that Molloy girl?”

Money for Nothing, ch. 7.1 (1928)

Owing to the fact that Lord Emsworth, in his woollen-headed way, had completely forgotten to inform him of the exodus to Matchingham Hall, he was expecting to meet a gay and glittering company at the meal, and had prepared himself accordingly.

Summer Lightning, ch. 13.2 (1929)

I was, in fact, beginning to feel pretty censorious about my former self, for I can’t stand those woollen-headed, thriftless fellows who never think of the morrow, when I was brought up short by the sound of footsteps approaching the front door.

Laughing Gas, ch. 8 (1936)

The ecstasy which always came to the vague and woollen-headed peer when in the society of this noble animal was not quite complete, for she had withdrawn for the night to a sort of covered wigwam in the background and he could not see her.

Full Moon, ch. 1.1 (1947)

The day was so fair, the breeze so gentle, the sky so blue and the sun so sunny, that Lord Emsworth, that vague and woollen-headed peer, who liked fine weather, should have been gay and carefree, especially as he was looking at flowers, a thing which always gave him pleasure.

“Birth of a Salesman” (1950; in Nothing Serious, 1950)

restoratives *

See Sam the Sudden.

a bulldog trying to swallow half a cutlet *

Clapham ... Cricklewood (p. 124)

Cricklewood is in north London, Clapham is south of the river, about ten miles away. The implication is that only someone as absent-minded as Biffy could get the two mixed up.

Honoria Glossop (p. 126 ff) °

Bertie’s first engagement to Honoria and Jeeves’s strategy for getting him out of it are recounted in “Scoring Off Jeeves” and “Sir Roderick Comes to Lunch” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

getting outside my morning tea and toast *

See Thank You, Jeeves.

managed to shin up a tree *

My mental attitude, in short, was about that of an African explorer who by prompt shinning up a tree has just contrived to elude a quick-tempered crocodile and gathers from a series of shrieks below that his faithful native bearer had not been so fortunate. I mean to say he mourns, no doubt, as he listens to the doings, but though his heart may bleed, he cannot help his primary emotion being one of sober relief that, however, sticky life may have become for native bearers, he, personally, is sitting on top of the world.

The Mating Season, ch. 24 (1949)

welterweight *

A boxer weighing at least ten stone (140 lb, 63.5 kg) and less than eleven stone (154 lb, 69.9 kg) by the National Sporting Club rules of 1909; in later subdivisions of the class, the upper limit was 147 lb (66.7 kg).

a laugh like a squadron of cavalry charging over a tin bridge *

Honoria, a ghastly dynamic exhibit who read Nietzsche and had a laugh like waves breaking on a stern and rock-bound coast

“Jeeves and the Yule-Tide Spirit” (1927; in Very Good, Jeeves, 1930)

Freud *

This seems to be the only time that Wodehouse refers by name to Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalytic theory.

the What is Wrong With This Picture brigade *

See Uncle Dynamite.

old cork *

The lady said: “Awfully sorry I’m late, old cork.”

Sam in the Suburbs/Sam the Sudden, ch. 4 (1925)

“Algy, old cork, I was just going to ring you up to say I would.”

“The Passing of Ambrose” (1928; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929/30)

The shot is not on the board *

rabbits in his bedroom *

See “Sir Roderick Comes to Lunch” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923).

off my onion *

See off his onion in Sam the Sudden.

forbid the banns (p. 130)

To object to a proposed marriage. From the custom of “reading the banns,” i.e. announcing the forthcoming marriage on three consecutive Sundays before the wedding, in the church of the parish where the couple live. This custom still exists in the Church of England.

out of the soup *

See in the soup in The Inimitable Jeeves.

crust *

See under rind in Something Fresh.

curveted *

picking straws out of their hair *

See Bill the Conqueror.

press the bulb and nature would do the rest *

A possible distant echo of the longtime Kodak advertising slogan “You press the button, we do the rest”— famous in Britain as well as America since 1890 at least.

tremble like aspens *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

Death Rays *

In science fiction, beams of lethal power, dating back at least to The World Masters by George Griffith (1903).

Captain Bradbury’s glare … scorched Freddie like a death ray.

“Trouble Down at Tudsleigh” (1935; in UK Young Men in Spats and US Eggs, Beans and Crumpets)

The door had opened, and he was aware of something like a death ray playing about his person. Rupert Baxter was there, staring at him through his spectacles.

Uncle Fred in the Springtime, ch. 11 (1939)

In saying that Constable Potter’s glance was significant, we omitted to state that it was at the last of the Twistletons that it had been directed, nor did we lay anything like sufficient stress on its penetrating qualities. It was silly of us to describe as merely significant something so closely resembling a death ray.

Uncle Dynamite, ch. 9 (1948)

Penny’s look, which came shooting in his direction as he crossed the threshold, was of a different quality. It was like a death ray or something out of a flame-thrower…

Pigs Have Wings, ch. 11.2 (1952)

Heaven speed the cobras you drop down people’s chimneys, and if you want to destroy the world with that Death Ray of yours, go to it, boy.

Speaking to Fu Manchu in “Onwards and Upwards with the Fiends” (Punch, February 16, 1955)

mangling a bit of lunch *

Neither the OED nor Green’s Dictionary of Slang recognize Wodehouse’s humorously figurative sense of the verb, normally meaning to cut or hack something up roughly, causing damage.

“Watching the match,” he explained, pausing for a moment in his bun-mangling.

“The Heart of a Goof” (1924; in The Heart of a Goof, 1926)

We had just finished mangling the cutlets and I was sitting back in my chair, taking a bit of an easy before being allotted my slab of boiled pudding, when, happening to look up, I caught the girl Heloise’s eye fixed on me in what seemed to me a rather rummy manner.

“Without the Option” (1925; in this book)

“She sees him eating a poached egg, and the glamour starts to fade. She watches him mangling a chop, and it continues to fade.”

“Jeeves and the Old School Chum” (1930; in Very Good, Jeeves, 1930)

nose-bags *

Bertie is jokingly comparing the plates of lunch to the way that horses are fed their oats, from a bag literally tied around the horse’s nose.

one of those complete frosts *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

C-3 *

feast of reason and flow of soul *

See A Damsel in Distress.

nifty *

See under the nifties in Sam the Sudden.

dinner-pail *

What we might call a workman’s lunch box or bucket; here used as another joking way of referring to the plate on which the lunch was served. Don’t confuse “handed up” here (i.e. passing the plate to the servant for another helping) with the frequent euphemism “handing in his dinner pail”: see Money for Nothing.

British Empire Exhibition (p. 136) °

The British Empire Exhibition at Wembley opened in 1924. Due to its success it was extended into 1925. One would be lucky to cover the distance from central London to Wembley in 20 minutes today.

[Google Maps shows the most direct route from Berkeley Square to Wembley via A404 at 8.4 miles, typically 30 minutes by car in off-peak times and up to 1 hour 20 minutes in late afternoons.]

deaf chap *

Wodehouse used a variant of this joke in The Mating Season, ch. 5 (1949), in which Bertie is somewhat damped before telling it by learning that Esmond’s Aunt Charlotte is deaf.

“Well, there were these two deaf chaps in the train, don’t you know, and it stopped at Wembley, and one of them looked out of the window and said ‘This is Wembley’, and the other said, ‘I thought it was Thursday’, and the first chap said ‘Yes, so am I’.”

back to the basket *

This is the only instance so far found of this phrase in Wodehouse; a speculative explanation, suggested by Wodehouse’s known fondness for pets, might be paralleling it to reprimanding a naughty dog or cat by taking it from one’s lap and putting it back in the basket in which it sleeps.

puff-faced *

Not defined in the OED. From context, apparently meaning officious or self-important.

Poor old Bobby got all purple and puff-faced and looked as if he hadn’t a friend in the world.

Bobby Denby, a social friend of Mrs. Wodehouse and occasional house guest in London and New York, here having lost a hand at Bridge. (Letter to Leonora, 14 November 1923, in Yours, Plum, ed. Frances Donaldson)

His manner, however, was reassuring. Puff-faced, yes, but not fiend-in-human-shape-y.

Pop Stoker in Thank You, Jeeves, ch. 12 (1934)

“He simply looked puff-faced and said that he would never allow his daughter to marry a man who had no earning capacity.”

J. G. Butterwick in The Luck of the Bodkins, ch. 3 (1935)

He merely lined up beside me as if we were going to do a duet and stood there looking puff-faced.

Constable Oates in The Code of the Woosters, ch. 14 (1938)

“When I left the dining-room to go and look at the Derby Dinner, Bill was all for coming too. ‘How about it?’ he said to Biggar, and Biggar, looking very puff-faced, said ‘Later, perhaps. At the moment, I would like a word with you, Lord Rowcester’. In a cold, steely voice, like a magistrate about to fine you a fiver for pinching a policeman’s helmet on Boat Race night.”

Ring for Jeeves/The Return of Jeeves, ch. 9 (1953/54)

It was a revelation to me that a puff-faced poop like Stilton could have been capable of detective work on this uncanny scale.

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 10 (1954)

Jeeves didn’t think highly of Operation Upjohn. I told him about it just before starting out for the tryst, feeling that it would be helpful to have his moral support, and was stunned to see that his manner was austere and even puff-faced.

Jeeves in the Offing/How Right You Are, Jeeves, ch. 15 (1960)

‘I wish you wouldn’t use that word “pinch”,’ he said, looking puff-faced.

Bingley in Much Obliged, Jeeves/Jeeves and the Tie That Binds, ch. 11 (1971)

You might have thought that that would have cleaned everything up and made life one grand sweet song, as the fellow said, but no, she went on looking puff-faced.

Vanessa Cook in Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen, ch. 7 (1974)

exhibish *

Exhibition, in the 1920s slang style of shortening words for informal effect. Both Wodehouse and lyricist Ira Gershwin were noted for this style.

registering *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

a strange light shone in it *

at the eleventh hour *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

the many-headed *

See A Damsel in Distress.

cheviot lounge *

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

Act of God (p. 139)

A legal phrase used to refer to natural disasters for which no person can be held liable.

Palace of Industry (p. 140) °

Most of the exhibits Bertie mentions are recorded as being part of the exhibition. It’s not certain whether there was a Planters’ Bar or a Palace of Beauty, but there was a “Women’s Pavillion.” One of the most notable items, displayed in the Canadian Pavilion, was a life-size equestrian statue of the Prince of Wales made out of butter.

[Norman Murphy noted in A Wodehouse Handbook that Pears’ Soap sponsored The Palace of Beauty, in which twenty or so beautiful girls posed as Cleopatra, Helen of Troy, and so forth, and the West Indian Pavilion served Green Swizzles.]

Green Swizzles *

Once again Norman Murphy came to the rescue, even discovering a verse that was chanted by the barman while shaking the drink:

One of sour,

Two of sweet,

Three of strong,

Four of weak.

The Jamaican High Commission confirmed that this is the formula for an authentic Jamaican rum punch, mixing one measure fresh lime juice (sour), two measures uncolored sugar syrup (sweet), three measures white overproof rum (strong), and four measures of water, soda, or lemonade (weak); mix well and agitate (swizzle) with finely crushed ice.

[Added 2025-06-24: I’ve been reading this story for over half a century, and I think this is the first time that I noticed the double meaning of the title. Wodehouse uses “rummy” in the slang sense of “odd, peculiar” so often that I just now spotted that it can also refer to the rum in the Green Swizzle recipe. —NM]

divers blokes *

A varied group of men; see The Inimitable Jeeves.

Jiggle-Joggle (p. 142)

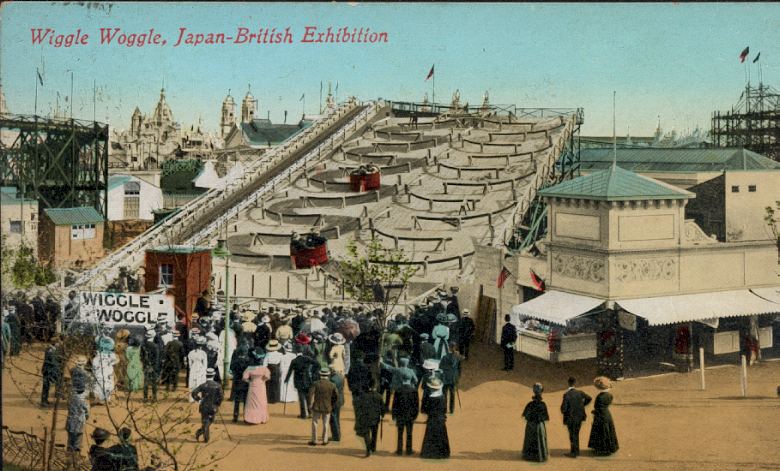

“DG” at “The Annotated Wodehouse Project” notes on another story that “A postcard from the Japan/British Exhibition at White City shows the Wiggle-Woggle to be an enormous incline. Two to four people climbed into a vehicle like an oversized bucket, and rode in that to the bottom, being buffeted along the descent by curved guide rails.” No doubt Wodehouse intended his readers to think of something similar in the current story.

Skee Ball (p. 142)

Arcade game, patented in 1909 by J. D. Estes of Philadelphia, and very popular in the 20s and 30s. It involved getting a wooden ball through one of a series of hoops at the end of a lane like a skittle alley.

delicately-nurtured *

See Blandings Castle and Elsewhere.

lovely woman loses a lot of her charm *

A faint allusion to an earlier phrase; see The Clicking of Cuthbert.

Queen Elizabeth or Boadicea or someone of that period (p. 144)

Boadicea or Boudica, queen of the Iceni, a British tribe living in East Anglia, killed fighting against the Romans in 61 CE.

‘Regions Cæsar never knew

Thy posterity shall sway,

Where his eagles never flew,

None invincible as they.’

William Cowper: Boadicea, an Ode (1782)

Elizabeth I (1533–1603) was queen of England 1558–1603. The ruff suggests her as the more likely of the two, and of course Bertie is centuries off in mentioning “that period”.

an important principal in the scene *

As he frequently does, Bertie is using theatrical jargon in describing situations in ordinary life.

jumping about like a lamb in the springtime *

knobkerrie (p. 145)

(Afrikaans) A short weighted club or throwing stick.

bob’s worth *

Good value for the admission price of one shilling (one-twentieth of a pound sterling).

Chiswick, 60873 (p. 145)

Continuing the running joke about London suburbs, it turns out that the young lady lives in Chiswick (or at least in the district covered by the Chiswick telephone exchange), which is in west London, not far from Wembley, but nowhere near either Clapham or Cricklewood.

It is a little surprising that she has a telephone: telephones remained an expensive luxury item out of the reach of most ordinary people in Britain until at least the 1960s, and were far more common in the USA. Wodehouse may have forgotten about this difference, having lived in the USA for the previous ten years. For the same reason, the five-digit phone number seems unlikely.

off his crumpet *

The OED gives one slang definition of crumpet as the head, especially in phrases such as “balmy/barmy in/on the crumpet” for being mad. Wodehouse’s version is not recorded in the OED, but in parallel with “off his onion” the meaning is clear.

scratch the fixture *

brooding over the cosmos *

He was a grave-looking boy with the pinched face of one on whom the cares of the world press heavily. He seemed worried about the cosmos.

Bill the Conqueror, ch. 11.2 (1924)

Amy was by nature a thoughtful dog. Most of her time, when she was not eating or sleeping, she spent in wandering about with wrinkled forehead, puzzling over the cosmos.

Sam the Sudden, ch. 22.2/Sam in the Suburbs, ch. 30 (1925)

Ferris was large, ponderous and gloomy. He seemed always to be brooding on something, probably the cosmos, and not to be thinking very highly of it.

Company for Henry, ch. 4 (1967)

It was Gally’s practice, when he favoured Blandings Castle with a visit, to repair after breakfast to the hammock on the front lawn and there to ponder in comfort on whatever seemed to him worth pondering on. It might be the Cosmos or the situation in the Far East, it might be merely the problem of whether or not to risk a couple of quid on some horse running in the 2.30 at Catterick Bridge.

A Pelican at Blandings, ch. 11.1 (1969)

parted brass rags (p. 146)

Naval expression: ratings used to share a bag of polishing rags with a colleague (a “raggie”), so parting brass rags was a consequence of separating after a disagreement. See Very Good, Jeeves.

fifteen thousand a year *

Accounting for inflation from 1925 to 2024, this is an income of roughly three-quarters of a million pounds in modern terms, or about a million US dollars per year.

Without the Option (pp. 148–175)

This story was originally published in the Saturday Evening Post, June 27, 1925 and in the Strand magazine, July 1925. It was published in book form in Carry On, Jeeves! (1925 in UK, 1927 in US). Page references are to the 1999 Penguin edition of Carry On, Jeeves, in which the story runs from pp. 148–175.

beak (p. 148)

Slang expression for a magistrate or a schoolmaster. The OED is unable to give a derivation, but there may be a link with the archaic thieves’ cant expression “harman beck” (beadle or constable).

pince-nez ... nose dive (p. 148)

Spectacles without earpieces attached to the nose (French: nose-pincher). “Nose dive” normally means to dive nose-first – Wodehouse, as usual doing something unexpected with a cliché, uses it here to mean “dive from the nose.”

five pounds *

The Bank of England inflation calculator suggests a multiplication factor of approximately 51 from 1925 to 2024, so this would be the rough equivalent of £255 or US$334 in modern terms.

Bosher Street Police Court (p. 149)

See Summer Lightning.

Leon Trotzky (p. 149) °

Lev Davidovich Bronstein (1879–1940). Three of the original versions of this story spell his adopted revolutionary surname as Trotzky, but the Strand version uses the more usual transliteration of Троцкий into the Roman alphabet as Trotsky. Member of the Central Committee of the Bolshevik party during the Russian revolution, Commissar for Military and Naval Affairs and founder of the Red Army. His ideas for spreading the revolution beyond Russia’s borders were opposed by Stalin, and he found himself squeezed out of power after 1922, eventually being forced into exile in 1927 and murdered in 1940. The magistrate would certainly have seen plenty of pictures of Trotsky in the papers.

aquatic contest (p. 149)

The Oxford and Cambridge boat race takes place on a four and a half mile course on the Thames (between Mortlake and Putney), on a Saturday during the Easter vacation. It was first held in 1829.

Additional details are in the notes to Laughing Gas and The Code of the Woosters.

the heart bowed down by weight of woe to weakest hope will cling *

See Sam the Sudden.

may a nephew’s curse *

A quotation from W. S. Gilbert’s libretto for the comic opera Patience (1881, with Arthur Sullivan).

trust in a higher power *

Here Bertie takes a familiar statement of religious faith or spirituality and applies it to Jeeves. Similarly, in ch. 4 of Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, Bertie “felt that my only course was to place myself in the hands of a higher power,” meaning Jeeves.

Conversely, in ch. 4 of The Code of the Woosters Bertie tells Gussie Fink-Nottle that “We must just put our trust in a higher power”; Gussie thinks that he means to consult Jeeves, but Bertie says that even Jeeves cannot help here. In ch. 20 of Jeeves in the Offing, Bertie says that the only thing left “is to put our trust in a higher power”; Aunt Dahlia asks Bobbie Wickham to go and fetch Jeeves, and Bertie goes along with that interpretation of his meaning.

climbed outside the pick-me-up *

intoning the responses (p. 152)

Intoning is a way of chanting on a single note practiced particularly in the Church of England. In the Anglican liturgy, Responses are the parts of the service which take the form of a scripted dialogue, usually between priest and clerk or between priest and congregation.

Beckley-on-the-Moor, in Yorkshire (p. 152)

Beckley is a common English placename, appearing in Durham, Hampshire, Kent, East Sussex and Oxfordshire. There is no Beckley in Yorkshire.

got the bird *

In the original theatrical sense of being hissed by an audience; see Leave It to Psmith for more.

banana oil (p. 155)

Isopentyl acetate (an ester used as a banana flavouring). Obsolete slang expression meaning nonsense, or insincere flattery.

fruity *

Mrs Spenser (p. 155) °

All four original versions of this story (in US and UK magazines, and in US and UK first editions of Carry On, Jeeves!) have “Mrs. Spencer” here. Reprint editions such as Penguin seem to prefer the spelling Spenser.

In The Inimitable Jeeves, Aunt Agatha is called Mrs. Gregson and her butler is called Spenser (see “Sir Roderick Comes to Lunch”). Elsewhere she is called Mrs. Spenser Gregson.

paling beneath my tan *

See The Mating Season.

Trumpington Road (p. 156)

Main road heading south out of Cambridge – the continuation of Kings Parade and Trumpington Street.

the whole strength of the company *

See Bill the Conqueror.

black cap (p. 158)

Judges would put on a black cap before pronouncing a sentence of death.

to mitt the female *

See Money for Nothing.

I think I may have told you before about this Glossop scourge *

We met her first in “Scoring Off Jeeves” (1922); the complications continued in “Sir Roderick Comes to Lunch” (also 1922; both collected as two chapters each in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923).

put the lid on it *

See Ukridge.

poultice *

See Hot Water.

colleges ... fifty-seven (p. 161)

In the 1920s, Cambridge University had only eighteen constituent colleges, plus two women’s colleges which were not then full members of the University. Bertie (who is elsewhere said to have been at Magdalen College, Oxford) is perhaps thinking of the famous “57 varieties” slogan of H. J. Heinz, which first appeared in the 1870s.

popped up through a trap *

See Bill the Conqueror.

Girton (p. 163) °

Women’s college. Founded at Hitchin in 1869, moved to a site two miles north of Cambridge in 1873.

Wodehouse’s cousin Helen Wodehouse (1880–1964), daughter of his father’s oldest brother Rev. Philip John Wodehouse, got her first class degree at Girton in 1902, having studied both mathematics and moral sciences. After receiving a D.Phil. from Birmingham in 1906, she lectured in philosophy there and chaired the department of education at the University of Bristol, before returning to Girton as Mistress of the college in 1931. One wonders if her braininess may have contributed to the portrayals of Honoria Glossop and Heloise Pringle. [NM]

all to the mustard *

Sticketh-Closer-Than-a-Brother (p. 163)

A man that hath friends must show himself friendly; and there is a friend that sticketh closer than a brother.

[Proverbs 18:24]

gasper *

British slang for an inexpensive or harsh cigarette.

The Trail of Blood

(p. 165)Oddly enough, the earliest book of this title I could find (by Charles Rushton) was published by Wodehouse’s own publishers, Herbert Jenkins, in 1929. Evidently the title stuck in someone’s mind.

The book of the same title by J. M. Carroll published in the US in 1931 turns out to be a history of the Baptist Church. Bertie would have enjoyed that!

the old onion *

Late Victorian British slang for the head, especially in the phrase off one’s onion for “mad, crazy,” which is the most frequent usage of the term by Wodehouse.

Mens sana in corpore sano *

St Luke’s (p. 168) °

There is a Catholic church of St. Luke in Cambridge, but it is not especially likely that Sir Roderick would be lecturing there. More likely is that Bertie or the author has misheard “Addenbrookes,” the name of the main Cambridge hospital.

Or perhaps Wodehouse is re-creating the fictional College of St. Luke’s at one of the great Universities, from the Sherlock Holmes story “The Adventure of the Three Students” by Arthur Conan Doyle. [NM]

bobbing or shingling *

Two of the terms for creating the short boyish haircuts adopted by young women in the 1920s. See Sam the Sudden for more information.

Hell’s foundations are quivering (p. 170)

one hundred and fifty miles (p. 171)

(ca. 240km) This distance from Cambridge suggests that Miss Sipperley lives somewhere in the North Riding.

a couple of parasangs (p. 171) °

The parasang is a Persian unit of measure, approximately equal to three miles (5km). One example in the OED for the figurative sense of parasang is taken from Jeeves in the Offing (1960).

barefoot dancer … Vision of Salome *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

bastille (p. 173)

Fortress in Paris, used as a prison in the 17th and 18th centuries. The storming of the Bastille on the 14th July 1789 was one of the great symbolic events of the French Revolution, although there were few if any political prisoners there at the time.

failing to abate a smoky chimney *

See Summer Lightning.

move in a mysterious way (p. 173)

God moves in a mysterious way

his wonders to perform:

he plants his footsteps in the sea,

and rides upon the storm.

Deep in unfathomable mines,

with never-failing skill,

he treasures up his bright designs,

and works his sovereign will.

Ye fearful saints, fresh courage take;

the clouds ye so much dread

are big with mercy, and shall break

in blessings on your head.

Judge not the Lord by feeble sense,

but trust him for his grace;

behind a frowning providence

he hides a smiling face.

His purposes will ripen fast,

unfolding every hour:

the bud may have a bitter taste,

but sweet will be the flower.

Blind unbelief is sure to err,

and scan his work in vain;

God is his own interpreter,

and he will make it plain.

[Hymn; Words: William Cowper, 1774]

See Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit for other allusions to this hymn.

Fixing It for Freddie (pp. 176–197)

This story was originally published in the Strand Magazine in 1911 as the Reggie Pepper story “Helping Freddie.” The story first appeared in book format in 1919 in My Man Jeeves. It was published in amended form as a Jeeves & Wooster story in Carry On, Jeeves! (1925 in UK, 1927 in US). The first serial publication in this form is recorded as the Canadian Home Journal, September 1928. Page references are to the 1999 Penguin edition of Carry On, Jeeves, in which the story runs from pp. 176–197.

packing ... old kitbag (p. 176)

Pack up your troubles in your old kitbag

And smile, smile, smile

While you’ve a lucifer to light your fag

Smile, boys, that’s the style

What’s the use of worrying

It never was worth while

So: pack up your troubles in your old kitbag

And smile, smile, smile

[Popular song of the First World War, written by George Asaf and Felix Powell, (1915)]

last rose of summer (p. 176)

’Tis the last rose of summer,

Left blooming all alone,

All her lovely companions

Are faded and gone.

No flower of her kindred,

No rose bud is nigh,

To reflect back her blushes,

Or give sigh for sigh.

I’ll not leave thee, thou lone one,

To pine on the stem;

Since the lovely are sleeping,

Go sleep thou with them;

Thus kindly I scatter

Thy leaves o’er the bed

Where thy mates of the garden

Lie scentless and dead.

So soon may I follow

When friendships decay,

And from love’s shining circle

The gems drop away!

When true hearts lie withered

And fond ones are flown

Oh! who would inhabit

This bleak world alone?

[Irish song, by Sir John Stevenson (1761–1833)]

Morning Post (p. 176)

See Leave It to Psmith.

Marvis Bay (p. 177)

Marvis is a relatively frequent family name, but does not appear to occur in any British placename. There are a number of small seaside places in Dorset which would meet Bertie’s description.

“The Rosary” (p. 178)

The hours I spent with thee, dear heart,

Are as a string of pearls to me;

I count them over, every one apart,

My Rosary, my Rosary.

Each hour a pearl, each pearl a prayer,

To still a heart in absence wrung;

I tell each bead unto the end,

And there a cross is hung.

O memories that bless and burn!

O barren pain and bitter loss!

I kiss each bead, and strive at last to learn

To kiss the cross;

Sweetheart!- to kiss the cross.

[Song (1898), music by Ethelbert Woodbridge Nevin (1862–1901).]

With a name Wodehouse would have been proud to invent, he was one of the most famous American composers of his day but now largely forgotten; the words are by the justly obscure Robert Cameron Rogers. The song was a huge success at the time – the extreme banality of the melody is probably the reason it is the only tune Freddie can play.

married a man named Spenser (p. 185)

In The Inimitable Jeeves, Aunt Agatha is called Mrs Gregson and her butler is called Spenser (see “Sir Roderick comes to lunch”). Elsewhere she is called Mrs Spenser Gregson.

Bailey’s Granulated Breakfast Chips (p. 186)

The fashion for breakfast cereals started with Corn Flakes, invented in 1896 by the American physician and dietary reformer Dr John Harvey Kellogg at Battle Creek, Michigan and commercialised by his brother Will. The rapid success of the product led to many imitations being brought on the market – there is an entertaining fictionalised account in T. Corraghessan Boyle’s novel The Road to Wellville (1993). Bailey’s Granulated Breakfast Chips appears to be an invented name.

Colney Hatch (p. 187)

The Middlesex County Lunatic Asylum, later Friern Hospital, opened in 1851 in the hamlet of Friern Barnet, in what is now the north London district of New Southgate.

“Hearts and flowers” (p. 191)

Out amongst the flowers sweet,

Lingers pretty Marguerite,

Sowing with her hands so white,

Future blossoms, fair and bright.

And the sunbeams lovingly

Kiss sweet Marguerite for me

Kiss my little lady sweet,

Blue eyed gentle Marguerite!

When I say, “Oh Marguerite,

All my heart is at your feet,

Turn it to a garden fair,

See it blossom ’neath your care.

“Till it yields for you alone

Wond’rous fragrance all your own.

And its sweetest flowers shall grow,

For my Marguerite I know!”

Blushes deepen in her cheek,

Ere the shy red lips can speak,

“Ah! but what if weeds should grow,

Mongst the flowers you bid me sow?”

“Love will pluck them out,” I cry,

“Trust me, Marguerite so shy,

Let my heart your garden be,

Give the seeds of love to me.”

[Music by Theodore Moses-Tobani (1893) Words (added in 1899) by Mary D. Brine.]

A standard of the cinema pianist’s repertoire for the romantic moments in silent films.

animal-trainer blokes (p. 193)

Possibly a reference to the work of Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) on the conditioned reflex, published in 1903. Pavlov trained dogs to associate the ringing of a bell with feeding, and found that the dogs began to salivate when the bell was later rung in the absence of food.

about the size of the Albert Memorial (p. 195)

The 53m high monument to Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, in London’s Hyde Park was designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott and included figures by several leading Victorian sculptors. The seated statue of Albert himself is by J. H. Foley and Thomas Brock. The monument took twelve years to build, being completed fourteen years after Albert’s death, in 1875. It has recently undergone a major restoration. The monument is regarded as one of the most important works of gothic revival architecture.

French windows (p. 195)

Glazed double doors opening from a room onto a patio or veranda.

From Bertie’s comment (don’t forget the flurry of theatrical language earlier when Bertie is rehearsing Tootles) it is clear that the young hero entering through the French windows was already a dramatic cliché, even then.

dresses long enough to be trodden on (p. 195)

When this story first appeared in 1919, hemlines were still down at the ankle; by 1925 they had reached the knee.

Dumb Brick *

As far as can be determined from a Google Books search, Wodehouse seems to have coined, or at least have been the first to have recorded in print, this epithet for an unintelligent and untalkative person; all references returned in the search prior to 1925 refer to silent walls of actual brick. In the initial appearance of this story in 1919, Freddie was the World’s Champion Chump. Wodehouse’s first-published use of the term was in Sam the Sudden, serialized in the Saturday Evening Post as Sam in the Suburbs; in the July 18, 1925, concluding episode, Chimp Twist refers to Soapy Molloy as “that poor dumb brick.” See Sam the Sudden for its location in the print book. [NM]

six children, a nurse, two loafers, ... (p. 196)

This sort of catalogue is a favourite comic device of Wodehouse’s: Compare the list of spectators of Ashe Marson’s exercises in Something Fresh, Chapter 1.

Clustering Round Young Bingo (pp. 198–227)

This story was originally published in the Saturday Evening Post, February 21, 1925, and in the April 1925 Strand magazine, then collected in Carry On, Jeeves! (1925 in UK, 1927 in US). Page references are to the 1999 Penguin edition of Carry On, Jeeves, in which the story runs from pp. 198 to 227.

For “cluster round” in the story title, see Very Good, Jeeves. °

knee-length underclothing (p. 198)

Compare the reference in Chapter 1 of Right Ho, Jeeves to “the knee-length.”

Milady’s Boudoir (p. 198) °

Aunt Dahlia’s struggling magazine and Bertie’s sole literary effort are frequently mentioned in later stories. Wodehouse contributed stories to a number of women’s magazines, including Cosmopolitan, Redbook, the Ladies’ Home Journal, and the Woman’s Home Companion.

raspberry *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

... author blokes have bald heads (p. 199)

Wodehouse is making a joke against himself: he had lost most of his hair by this time. Photographs from the twenties almost always show him wearing a hat or cap.

sixpence *

In 1925, that would have been the equivalent of 12 cents in American coin; accounting for inflation to 2023, based on consumer price index data, a rough equivalent would be US$2.16, according to measuringworth.com.

bijou *

From the French for jewel; figuratively something small, of careful workmanship.

love-light (p. 199) *

See Galahad at Blandings.

diametrically in the centre of the eyeball (p. 199)

As a diameter is – by definition – a line through the centre of a sphere or circle, this is tautologous. Bertie is saying the same thing twice, for comic emphasis.

Peabody and Simms (p. 199)

Apparently fictitious. Just possibly, the names might have been suggested by two nineteenth century American intellectuals, from opposite sides of the Mason-Dixon line, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody (1804–1894), writer and educationalist, disciple of Froebel, and sister-in-law to Hawthorne; and William Gilmore Simms (1806–1870), novelist and biographer, best known as author of historical fiction set in his native South.

Prince of Wales (p. 200)

Courtesy title of the British crown prince (heir to the throne). The future Edward VIII and Duke of Windsor (1894–1972) received the title in 1910. He was very popular as Prince of Wales, and had a powerful impact on men’s fashions, starting the move towards a less formal look (soft collars and Windsor-knotted ties, sports jackets, V-neck sweaters, etc.). It is not surprising that Jeeves, as a sartorial conservative, would have disapproved.

Le Touquet (p. 200) °

Le Touquet-Paris Plage is a seaside resort in northern France, about 15km south of Boulogne. Still very fashionable in the twenties, although it declined in popularity with the upper classes when they started going to the Riviera in summer as well as winter.

Plum and Ethel Wodehouse had visited Le Touquet in 1924, and ten years later had leased a house known as Low Wood there, part of an attempt begun in 1931 to deal with tax obligations to England and America by becoming a resident of France. Wodehouse was living at Low Wood when the Germans occupied France in 1940, and was taken into internment by the Germans as a civilian citizen of an enemy nation.

with soft silk shirt complete (p. 200) *

See Bill the Conqueror.

“…you know what housemaids are.” (p. 200) *

Both magazine versions follow this with Bertie’s explanation: “Females who get housemaid’s knee.”

typhoon, simoom, or sirocco (p. 200)

Typhoon: violent storm occurring in South Asia, especially from July to October.

Simoom: sand-wind which sweeps across the African and Asian deserts in the spring and summer

Sirocco: oppressively hot wind, blowing from the north coast of Africa over the Mediterranean

Covent Garden ... a deep top-dressing of old cabbages and tomatoes (p. 201) °

Covent Garden was the site of London’s fruit and vegetable market from 1671 until 1974, when it moved to a new site south of the river. It remains an area favoured by publishers and the like.

Top-dressing is the British gardener’s term for vegetable matter, compost, manure, and the like applied to the surface of soil to enrich it, to control weeds, and to limit evaporation; the American equivalent would be “mulch.”

Mrs. Little (p. 201)

Bingo Little and his future wife first appeared in the stories collected in The Inimitable Jeeves. They also appear without Jeeves and Wooster in some stories in the collection Eggs, Beans and Crumpets.

east of Leicester Square (p. 201)

Leicester Square is at the eastern end of London’s aristocratic district, Mayfair, a few streets west of Covent Garden.

tripe *

A figurative adaptation of the word, originally meaning parts of bovine stomachs used for food. The term was applied to low-grade or worthless speech and writing in the late nineteenth century; the OED citations have the word in quotation marks as slang in Victorian times, and without quotation marks beginning in 1902.

pie (p. 201)

Trivial (contraction of ‘easy as pie’).

This Kid Mitchell was looked on as a coming champ in those days. I guess I looked pie to him.

The Coming of Bill (1920) i. v. 54

“How do you propose to make your entry?”

“Easy as pie. Odd-job man. They always want odd-job men.”

Sam the Sudden (1925) xix. 156

If by merely speaking she could stir him so, to bend him to her will when they met face to face would be pie.

“The Purification of Rodney Spelvin” (1925; in The Heart of a Goof, 1926)

“Interesting Llewellyn in Silver River would be pie, but I’d also have to interest her, and she’s not the right woman for that.”

Pearls, Girls & Monty Bodkin (1972) iv. 53

hummers (p. 201)

Originally a hummer was someone or something that showed great activity, but by the early 20th century it had also colloquially come to mean someone or something of particular excellence.

“Well, you can’t get there quicker than in my car. She’s a hummer!”

A Damsel in Distress (1919)

a wicked ragoût (p. 202) °

“Wicked” in the slang sense of excellent seems to have come in early in the 20th century. A ragout is a kind of stew or goulash made with meat and vegetables.

The first literary citation in the OED for “wicked” in the slang sense is from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise in 1920.

immersed to the gills *

As with tonsils, Wodehouse uses “gills” in jocular variants on “up to the neck” meaning “completely.”

For another instance, see Very Good, Jeeves.

She married my Uncle Thomas *

Some readers have concluded from this passage that Bertie knew Uncle Thomas before he knew Aunt Dahlia; this is not the only conclusion that can be drawn. See the discussion below regarding Mr. George Travers.

the year Bluebottle won the Cambridgeshire (p. 202) °