The Code of the Woosters

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

The following notes attempt to explain cultural, historical and literary allusions in Wodehouse’s text, to identify his sources, and to cross-reference similar references in the rest of the canon. These notes were originally written by Terry Mordue, and can be seen in their original form here. They have been edited, expanded, and somewhat reformatted by Neil Midkiff [NM] and others as credited below. Notes flagged with ° are substantially revised; notes flagged with * are new in 2021–25.

The Code of the Woosters was published simultaneously in the UK and US, by Herbert Jenkins, London, and by Doubleday, Doran, New York, on 7 October 1938. It was serialized in

the Saturday Evening Post and the Daily Mail prior to book publication; see this page for details of serial appearances.

The Code of the Woosters was published simultaneously in the UK and US, by Herbert Jenkins, London, and by Doubleday, Doran, New York, on 7 October 1938. It was serialized in

the Saturday Evening Post and the Daily Mail prior to book publication; see this page for details of serial appearances.

Page references are to the Penguin edition, using the 1953 “set in Monotype Garamond” plates, reprinted at least through the 1980s. For those using other editions, here is a cross-reference table (the link opens in a new browser tab or window) to the pagination of some other available editions.

|

Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 |

Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 |

Chapter 1 (pp. 5–20)

Autumn — season of mists and mellow fruitfulness (p. 5)

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eaves run;

: Ode, “To Autumn” (1819)

one of those bracers of yours (p. 5)

We learn of Jeeves’s “pick-me-ups,” “morning revivers,” or “bracers” in several stories; the first mention (in story chronology) is in “Jeeves Takes Charge” (1916):

It is a little preparation of my own invention. It is the dark meat-sauce that gives it its color. The raw egg makes it nutritious. The red pepper gives it its bite. Gentlemen have told me they have found it extremely invigorating after a late evening.

In other stories the recipe provides aid and succour to other gentlemen as well. [NM]he shimmered out (p. 5)

Jeeves’s movements in and out are usually described as noiseless and somewhat mystical. Here the allusion seems to be to a mirage, now seen, now unseen. [NM]

Drones (p. 5)

The Drones Club in Dover Street is a magnet for Wodehouse’s idle young men about London, named after the male bees who do no work. It is first mentioned in Jill the Reckless/The Little Warrior (1920) and continues through Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen/The Cat-nappers (1974). Norman Murphy (In Search of Blandings) identified aspects of the Bachelors’ Club, the Bath Club, and Buck’s Club contributing elements to its creation. [NM]

Gussie Fink-Nottle … Madeline (p. 5)

See Right Ho, Jeeves (1934) for the backstory of their relationship. The events of that novel take place during the “preceding summer” a “few months” before this novel in story time. [NM]

Sir Watkyn Bassett, CBE (p. 5)

Sir Watkyn Bassett’s CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire) does not entitle him to be called “Sir,” as it is one rank below a knighthood (which would be denoted by KBE — Knight Commander). And if, along with the “pot of money,” he had inherited a baronetcy, one would have expected him then to be described as “Sir Watkyn Bassett, Bart., CBE.” Also, other baronets in the canon, such as Sir Gregory Parsloe, are usually described as such, but nowhere is there any mention that Sir Watkyn is a baronet.

We must assume, therefore, that he is a Knight Bachelor, an honour that entitles the holder to be called “Sir” but, because it does not belong to one of the established Orders of Chivalry, is not normally marked by any post-nominal letters. Knights Bachelor are by no means unusual: well-known modern examples are England’s former rugby coach, Sir Clive Woodward CBE, and actor Sir Anthony Hopkins CBE.

Jael the wife of Heber (p. 5)

Howbeit Sisera fled away on his feet to the tent of Jael the wife of Heber the Kenite: for there was peace between Jabin the king of Hazor and the house of Heber the Kenite.

And Jael went out to meet Sisera, and said unto him, Turn in, my lord, turn in to me; fear not. And when he had turned in unto her into the tent, she covered him with a mantle.

. . . .

Then Jael Heber’s wife took a nail of the tent, and took an hammer in her hand, and went softly unto him, and smote the nail into his temples, and fastened it into the ground: for he was fast asleep and weary. So he died.

And, behold, as Barak pursued Sisera, Jael came out to meet him, and said unto him, Come, and I will shew thee the man whom thou seekest. And when he came into her tent, behold, Sisera lay dead, and the nail was in his temples.

Bible: Judges 4:17–18, 21–22

Wodehouse was particularly fond of this story, which gets a mention in many of the books and stories, including “The Salvation of George Mackintosh” in The Clicking of Cuthbert, Ring for Jeeves ch. 18 (and the earlier play, Come On, Jeeves, Act III); Much Obliged, Jeeves ch. 8; Cocktail Time ch. 2; and Uncle Dynamite ch. 11.

tissue restorer … reviver (p. 5) *

A hint that Jeeves’s mixture contains a little of “the hair of the dog” (i.e. some alcohol). Bertie frequently calls cocktails “tissue restorers”; see Sam the Sudden. [NM]

nosegay (p. 6)

Typically a term used for a bouquet of flowers to be held in the hands, rather than a collection of travel brochures. [NM]

gruntled (p. 6)

The Oxford English Dictionary cites this, Wodehouse’s back-formation from “disgruntled,” as the first usage of the word. [NM]

sands are running out (p. 7)

From the old-fashioned hourglass, a metaphor for the time becoming shorter until a future event. [NM]

Boat Race night (p. 7)

The events described here are recorded in “Without the Option” (collected in Carry On, Jeeves!) in which the Bosher Street magistrate is unnamed; he remarks that “I am aware that on the night following the annual aquatic contest between the universities of Oxford and Cambridge a certain licence is traditionally granted by the authorities.” Beginning in 1829 and annually since 1856 except during the two world wars, a rowing race between the eight-man boats of Oxford and Cambridge has been held on the river Thames from Putney to Mortlake, about 4.2 miles. The 2017 race was held on Sunday, April 2. This is one of the most popular sporting events in Britain, with over 250,000 spectators lining the banks of the river to watch. No doubt some spectators still get in trouble for excesses of celebration (or the reverse) on the night of the event.

Bertie seems to have had at least two such encounters with the police; he recalls being hauled up before the Vine Street magistrate during his second year at Oxford in Thank You, Jeeves (along with Chuffy Chuffnell) and Right Ho, Jeeves. He also recalls, in “Jeeves and the Chump Cyril,” having to bail out a pal who got pinched every Boat Race night. Other Wodehouse characters who celebrate to excess on Boat Race night include Oliver “Sippy” Sipperley in “Without the Option,” Lord Datchet in Piccadilly Jim, and Barmy Fotheringay-Phipps (recalled in “The Word in Season” and Joy in the Morning). Tipton Plimsoll pledges not to go on a real toot except on special occasions like Boat Race Night in Full Moon, ch. 10.5. [NM]

Morten Arnesen points us to a web article with historical news reports since 1875 of Boat Race Night revelry and references to Wodehouse’s use of it in his fiction.

Bosher Street (p. 7) *

A (fictitious) police court; see Summer Lightning.

five of the best (p. 7) *

Five pounds; roughly equivalent to £340 or US$450 in modern terms. See below.

a pot of money (p. 7) *

See Ukridge.

not forgotten that man of wrath (p. 7)

In Homer’s Odyssey, the name Odysseus means “man of wrath.” See Love Among the Chickens for further literary parallels.

toddling (p. 7) *

two shakes of a duck’s tail (p. 8)

Idiom: very quickly. Wodehouse is using a variant of the more common “two shakes of a lamb’s tail,” a phrase that is thought to have originated in the US in the early 19th century.

impending doom (p. 8) *

These two words have long been coupled in literature; Wodehouse uses the phrase as early as 1912 (The Prince and Betty, US edition) and titled a 1926 short story “Jeeves and the Impending Doom.” Monty Bodkin is “becoming conscious of an impending doom” in Heavy Weather, ch. 7 (1933). Lord Shortlands flees to London to “postpone the impending doom” in Spring Fever, ch. 20 (1948). Bertie Wooster uses it for the threat of being married to Florence Craye in Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 13 (1954), and for Sir Watkyn Bassett’s refusal to give Stinker Pinker a vicarage in Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 19 (1963).

Anatole, her French cook (p. 8) *

See “Clustering Round Young Bingo” (1925) for the story of how Anatole came to cook for the Travers household.

browsing (p. 8) *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

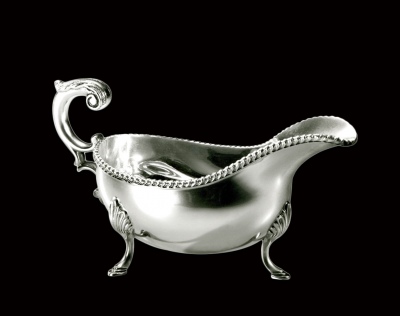

sconces and foliation … scrolls, ribbon wreaths in high relief and gadroon borders (p. 8)

sconces and foliation … scrolls, ribbon wreaths in high relief and gadroon borders (p. 8)

Examples of silversmiths’ decorative patterns; sconces in this context are the tubular sockets of a candelabrum in which candles are inserted. Foliation is a leaf pattern; scrolls and ribbon wreaths are self-explanatory; high relief means deeply carved and/or highly molded to stand out from the surrounding surface. Gadroon borders are fancy edges of silver or gold items decorated with many small adjacent convex curves to give a beaded or rippled effect, as in the George II sauce boat at right. [NM]

up to her Marcel-wave (p. 8) °

The Marcel-wave was introduced in 1872 by a Parisian hairdresser, Marcel Grateau, who had the idea of using a heated curling iron to produce natural-looking waves. Grateau’s idea revolutionised the art of women’s hairdressing and started a fashion that remained popular for nearly fifty years.

The US magazine serial and US first edition have “marcelle wave” here.

[Not merely women’s hair; men with marcelled hair include Percy Pilbeam (Summer Lightning/Heavy Weather/Frozen Assets), Claude Winnington-Bates (Sam the Sudden), Stanhope Twine (Something Fishy), and some of the young men dancing at the Mustard Spoon night club in Money for Nothing. —NM]

“What the Well-Dressed Man Is Wearing” (p. 8)

The story of Bertie’s sole literary effort is told in “Clustering Round Young Bingo” in Carry On, Jeeves! [NM]

view-halloos . . . the Quorn, the Pytchley (p. 9)

“View-halloo” is the huntsman’s cry when a fox breaks cover.

The Quorn and the Pytchley are two well-known hunts in central England, the Quorn primarily in Leicestershire, with some coverts in Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, and the Pytchley straddling the Leicestershire–Northamptonshire border.

an antique shop in the Brompton Road — it’s just past the Oratory (p. 9)

The London Oratory, built in 1893, was the first new Roman Catholic church to be built in London since the 16th-century Reformation. It is situated on Brompton Road, South Kensington, almost adjacent to the Victoria and Albert Museum.

talking through the back of her neck (p. 9) *

Slang for talking nonsense. Green’s Dictionary of Slang online gives citations [you may need to click the horizontal-lines icon to the right of 2003 on the timeline to show quotations] for various forms of this phrase, including a 1912 one attributing “talk from the back of his head” to a Maori proverb. The precise form is cited from “Sapper” (H. C. McNeile, author of the Bulldog Drummond series) in 1924 and from Wodehouse in 1934 (Right Ho, Jeeves).

Wodehouse uses it several times, half-a-dozen in Bertie’s voice and half-a-dozen or so elsewhere. The latest so far found:

He seemed to me to be talking through the back of his neck, the last thing you desire in a personal attendant.

Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 24 (1963)

The scales fell from my eyes (p. 9)

And immediately there fell from his eyes as it had been scales: and he received sight forthwith, and arose, and was baptized.

Bible: Acts 9:18. See Biblia Wodehousiana.

register scorn (p. 9) *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

nolle prosequi (p. 10)

Latin: will not prosecute. In English law (and, with substantially the same meaning, in US law), nolle prosequi is a technical term which signifies a formal undertaking by the plaintiff in a civil action, or by the attorney-general in a criminal action, that he intends to proceed no further with the action.

Bertie is very fond of nolle prosequi, which he invariably interprets as representing that he is unable to do something.

oscillate the bean (p. 10) *

shake the head; bean is US baseball slang for the head, as in bean ball. The OED cites Wodehouse from 1924’s Bill the Conqueror:

Have I got to clump you one on the side of the bean?

my little chickadee (p. 10)

In North America, “chickadee” refers to any of about half-a-dozen species of songbirds of the genus Parus, members of which, elsewhere in the world, are commonly known as tits or titmice.

Aunt Dahlia seems to be using the term affectionately; in colloquial English, “chick,” “chick-a-biddy,” and “chick-a-diddle” are all used as affectionate forms of address to a child, and it is possible that “chickadee” is a corruption of the last of these.

[The American comedian W. C. Fields (William Claude Dukenfield, 1880–1946) first spoke this endearment in the 1932 film If I Had a Million and freely inserted it in his scripts thereafter; his 1940 film pairing with Mae West was even titled My Little Chickadee. —NM]

as cool as some cucumbers, as Anatole would say (p. 11) *

This is one of the phrases that Wodehouse borrowed from Barry Pain’s The Confessions of Alphonse (1917; reprinted in Humorous Stories, 1930). The narrator of the stories in that book is a French waiter whose English is easily recognizable as the source of Anatole’s mangled expressions. “And he get up and reach for his hat as cool as some cucumbers” comes from Alphonse, for instance.

“There he was, advancing on you with glittering eyes and foam-flecked lips, and you drew yourself up as cool as some cucumbers, as Anatole would say, and said ‘One minute, Spode, just one minute. It may interest you to learn that I know all about Eulalie.’ ”

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 15 (1954)

She remained what Anatole would have called as cool as some cucumbers.

Much Obliged, Jeeves, ch. 6 (1971)

tight as an owl (p. 11) *

See Sam the Sudden.

the summer afternoon … when Gussie, … full to the back teeth with the right stuff, had addressed … Market Snodsbury Grammar School (p. 11)

See Right Ho, Jeeves, chapter 17. [NM]

publicans (p. 11)

Bertie’s use of “publicans” for “members of my public” seems to be his own invention; more usual senses of the word are the tax-collectors who worked for Rome in New Testament times, tax-collectors generally, heathens or unbelievers, and those who owned or ran public taverns. [NM]

bimbos (p. 11)

Bertie uses the older sense of the word, originally from the US in the 1910s, of a chap or fellow, referred to informally or sometimes contemptuously. Later in the 1920s the term began to be applied in a derogatory way to women, especially ones more noteworthy for looks than for brains or virtue, and that sense is better known today. [NM]

shell-like ears (p. 11–12) *

Victorian cliché for delicately-formed feminine ears:

This, with more tender logic of the kind,

He poured into her small and shell-like ear

Thomas Hood: “Bianca’s Dream”

Sentences so fiercely flaming

In your tiny shell-like ear,

I should always be exclaiming

If I loved you, Phœbe, dear.

W. S. Gilbert: “To Phœbe” from the Bab Ballads.

don the spongebag trousers (p. 12)

According to the OED, sponge-bag trousers are “men’s checked trousers, patterned in the style of many sponge-bags”; the first cited usage is in novelist Virginia Woolf’s Voyage Out, in 1915. [These are worn only as part of the “morning suit”; see the Gentlemen at Ascot illustration in this brief introduction with some period illustrations online. —NM]

the fatheaded girl thought I was pleading mine (p. 13) *

See Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 10 (1934).

she handed Gussie the temporary mitten (p. 13) °

Colloquial: jilted him temporarily. The earliest use so far found in Wodehouse for breaking an engagement:

“He was keeping company with a young lady once who got saved and give him the mitten the same evening, so he’s prejudiced.”

“Keeping It from Harold” (1914)

In addition to breaking an engagement, the phrase can also refer to someone being dismissed from his job:

It transpiring, moreover, that he had looted a lot of other things here and there about the place, I was reluctantly compelled to hand the misguided blighter the mitten…

“Jeeves Takes Charge” [collected in Carry On, Jeeves (1925)]

The origin is unknown, but it perhaps derives from the Latin mittere, to send.

Also used in The Inimitable Jeeves, Carry On, Jeeves!, The Girl on the Boat, Money in the Bank, Very Good, Jeeves, Mr. Mulliner Speaking, Uncle Fred in the Springtime, Summer Lightning, Thank You, Jeeves, and probably many others.

straightened out at the eleventh hour (p. 13) °

See Love Among the Chickens and Biblia Wodehousiana.

the two pills (p. 13) *

See Hot Water.

within an ace of (p. 13) *

See Leave It to Psmith.

the sort of hornswoggling highbinder (p. 14)

American slang. To hornswoggle is to cheat, to pull the wool over someone’s eyes.

Would she have the generosity to realize that a man ought not to be held accountable for what he says in the moment when he discovers that he has been cheated, deceived, robbed—in a word, hornswoggled?

The Little Warrior/Jill the Reckless, ch. 19 (1920/21)

The “High-Binders” was the name of a gang of lawless vagabonds that operated in New York early in the 19th century. The name subsequently came to be applied abusively to denote a swindler, especially a fraudulent politician.

hailed a passing barouche (p. 14)

See Summer Moonshine.

Although the barouche was the height of fashion in the first half of the 19th century, by the first half of the 20th century barouche-spotting had ceased to be a worthwhile activity, except during State processions. [Bertie is just using a jocular substitute for “taxicab” here, I think. —NM]

act of kindness (p. 14) *

The Boy Scout requirement to do a daily act of kindness forms part of the plot of “Jeeves Takes Charge” (1916).

the dead past was the dead past (p. 15)

See Sam the Sudden.

hep (p. 15) *

See Money for Nothing.

up-and-down (p. 15) *

wind-shields (p. 15) *

So far, searches in the OED and slang dictionaries have not yet uncovered this colloquialism for “eyeglasses”; this may be a Wodehouse coinage. He uses it in “The Story of Cedric” (1929; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929); of Gussie Fink-Nottle in The Mating Season, ch. 10 (1949); of Percy Gorringe in Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 15 (1954). US edition of this book has windshields without hyphen.

salver (p. 15) *

See Leave It to Psmith.

rising on stepping-stones of his dead self (p. 16)

See Something Fresh.

to the gills (p. 17) *

See Carry On, Jeeves!.

the better the day, the better the deed (p. 17) *

A conventional proverb, often used as an excuse for doing work on a Sunday or other religious holiday. The Oxford Dictionary of Proverbs finds a 14th-century French source: a bon jour bone euvre.

distinguish between meum and tuum (p. 17)

See Something Fresh.

give Aunt Dahlia’s commission the miss-in-balk (p. 17)

get outside another of Jeeves’s pick-me-ups (p.17)

Wodehouse did not invent the phrases “get outside” and “wrap oneself round” as humorous inversions of the act of putting food and drink inside oneself, but he did much to popularize these uses, beginning in 1906; see “How Kid Brady Joined the Press” and the endnote there on this phrase. [NM]

harts panting for cooling streams (p. 17–18)

As the hart panteth after the water brooks,

so panteth my soul after thee, O God.

Bible: Psalms 42:1

The phrase that Wodehouse uses is from a paraphrase of Psalm 42 made by Nahum Tate and Nicholas Brady in their English Metrical Psalter (New Version), published in 1696:

As pants the hart for cooling streams

When heated in the chase,

So longs my soul, O God, for Thee

And Thy refreshing grace.

See also Money in the Bank.

I wasn’t expecting the heart to leap up (p. 18)

See Summer Moonshine.

It was a silver cow (p. 18)

It was a silver cow (p. 18)

From Bertie’s description, can this be anything other than the cow-creamer pictured, or another one by the same maker? See the Victoria & Albert Museum site for more on this item, made in London in 1758–59 by John Schuppe. It is indeed “about four inches high” (9.6 cm) and “six long” (14.8 cm). The V&A web page summary tab mentions that “Such was their renown that they merited inclusion in 20th-century literature: Bertie Wooster, the hero of tales by the author P. G. Wodehouse, found these cow creamers quite disgusting.” [NM]

cudster (p. 18)

Clearly a term for “one that chews cud” but not included in the OED nor found in this sense in a Google Books search, so apparently a coinage by Wodehouse. [NM]

a different and a dreadful world (p. 19) *

See Very Good, Jeeves.

skipping like the high hills (p. 20)

“leaping” in the US first edition; omitted in the US magazine serial.

The voice of my beloved! behold, he cometh leaping upon the mountains, skipping upon the hills.

Bible: Song of Solomon 2:8

The mountains skipped like rams, and the little hills like lambs.

Bible: Psalms 114:4

Why leap ye, ye high hills?

Bible: Psalms 68:16

This was one of Wodehouse’s favourites and he continued using it almost to the end:

When she went off unexpectedly under their feet like a bomb, strong men were apt to lose their poise and skip like the high hills.

Quick Service, ch. 11 (1940)

You will start skipping like the high hills, not that I’ve ever seen high hills skip, or low hills for that matter.

Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen, ch. 16 (1974)

Though none of the Biblical sources exactly matches Wodehouse’s usage, the example from Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen suggests that he may have had Psalm 114 in mind.

up in the tenor clef (p. 20) *

A fairly obscure reference to the symbol indicating that a five-line musical staff has middle C on the second line from the top. This is used most often for instruments whose ranges cross the usual division between bass and treble staves, such as the bassoon, cello, and trombone. Most vocal music for tenors is written on the treble staff an octave higher than it is sung, and denoted with a treble-clef symbol with a small figure 8 just below it, which is sometimes loosely called a tenor clef. In any event, this means that Bassett had a high voice, and shows that Wodehouse’s musical knowledge was greater than sometimes claimed.

A fairly obscure reference to the symbol indicating that a five-line musical staff has middle C on the second line from the top. This is used most often for instruments whose ranges cross the usual division between bass and treble staves, such as the bassoon, cello, and trombone. Most vocal music for tenors is written on the treble staff an octave higher than it is sung, and denoted with a treble-clef symbol with a small figure 8 just below it, which is sometimes loosely called a tenor clef. In any event, this means that Bassett had a high voice, and shows that Wodehouse’s musical knowledge was greater than sometimes claimed.

in the neighbourhood of Sloane Square (p. 20)

Sloane Square lies south-east of Brompton Oratory, from which, by the shortest route “down byways and along side streets,” it is about 1 km distant.

turned off at the main (p. 20) *

The US equivalent would be in reference to electricity switched off at the fuse box or circuit-breaker panel.

Chapter 2 (pp. 21–36)

my earlier adventures with Gussie Fink-Nottle (p. 21) *

Recounted in Right Ho, Jeeves (1934).

a tidal wave of telegrams (p. 21) *

See Right Ho, Jeeves, chapter 3.

to re-establish the mens sana in corpore what-not (p. 22)

Bertie is quoting the Roman satirist Juvenal (55–130 AD):

Orandum est ut sit mens sana in corpore sano

Our prayers should be for a sound mind in a healthy body

Satires, X, 356

I sank into a c. and passed an agitated h. over the b. (p. 22)

Several possible interpretations of this sentence come to mind:

I sank into a coma and passed an agitated hour over the bedclothes;

or, I sank into a canter and passed an agitated horse over the bridge;

or, I sank into a crouch and passed an agitated hawser over the bow . . .

. . . but the likeliest is: I sank into a chair and passed an agitated hand over the brow.

all of a twitter (p. 22) *

the young seigneur (p. 22)

A seigneur is a feudal lord, in this case used figuratively to describe Bertie’s status as Jeeves’s employer.

lighted a feverish cigarette (p. 22)

An example of one of Wodehouse’s favourite devices, the transferred epithet. There are other examples later in this chapter and in ch. 5.

private school (p. 23) *

See p. 62, below.

telegraph … post office (p. 23) *

See p. 43, below.

Yes, that’s all very well… (p. 23) *

For one who had chided Bingo Little as a wasteful telegraphist in “The Metropolitan Touch” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923), Bertie is surprisingly wordy here. The messages he gets in return are more economically worded, e.g. “Surely merely twisting knife wound.”

a bag of three (p. 24) *

Here “bag” is used in the sportsman’s sense of the game, fish, or other targets caught in a day’s shooting, fishing, etc.

Popgood and Grooly (p. 24) *

See Ice in the Bedroom.

Jeeves left the presence (p. 24) *

Bertie, probably jocularly, refers to his bedroom as if it were a royal bedchamber and Jeeves a courtier.

got the pip about something (p. 25) *

From pip, a disease of poultry, humorously extended to anything that causes annoyance or depression in people. The OED cites Wodehouse’s use of it in The Inimitable Jeeves (1923; originally in the 1922 story “Aunt Agatha Takes the Count”).

hoggish slumber (p. 25) *

Norman Murphy (A Wodehouse Handbook) suggests a derivation from Shakespeare, either “hog in sloth” from King Lear or “swinish sleep” from Macbeth. But the immediate and precise source must be Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Ebb Tide (1893):

from the moment he rolled up the chart, his hours were passed in slavish self-indulgence or in hoggish slumber.

my fluttering old aspen (p. 25) *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

May green fly attack his roses (p. 26) *

See Something Fishy.

May all his hens get the staggers (p. 26)

The “staggers,” otherwise described as dizziness or vertigo, is not a disease but a symptom of some malady, such as lack of drinking water or worms in the nostrils. It affects mostly fat or over-fed birds. A bird afflicted with the staggers will often shake its body and turn round and round until it falls over and dies.

white ants, if there are any in England (p. 26)

There aren’t. “White ants” are termites, of the order Isoptera. Although not related to the ants (cockroaches are closer relatives), they are similarly social, living in colonies which may contain as many as a million individuals. They live in warm climates, especially in the tropics, where their huge mounds are a common feature. Termites are omnivorous and frequently do great damage, especially to wooden buildings and structures.

Of the 2000 or so known species of Isoptera, only two occur naturally in Europe, one confined to the Mediterranean coastlands, the other ranging as far north as northern Italy and the Bordeaux region of France.

this Machiavelli sicked him on to it (p. 27)

See A Damsel in Distress.

cigarette … advertisements, ought to have been nonchalant (p. 29) *

A slogan for Murad cigarettes; see this 1929 example.

bradawl (p. 29) *

See A Damsel in Distress.

through the seat (p. 29) *

J. Wellington Gedge … shooting from his chair as if Miss Putnam had left a pin in it.

Hot Water, ch. 1.2 (1932)

The monstrous word affected Jeff like a bradawl through the seat of the trousers.

Money in the Bank, ch. 8 (1942)

It was Pongo who spoke next, as if impelled to utterance by a jab in the trouser seat from a gimlet or bradawl.

Uncle Dynamite, ch. 9.1 (1948)

Indeed, she shot up as if a gimlet had suddenly penetrated the cushions and embedded itself in her person.

Sally Painter in Uncle Dynamite, ch. 11.4 (1948)

He quivered as if some hidden hand had thrust a bare bodkin through the seat of his chair.

Barmy in Wonderland, ch. 11 (1952)

He could indeed scarcely have started more violently if a bradawl had come through the seat of the deck chair in which he was reclining and impaled his lower slopes to the depth of an inch and a quarter.

Company for Henry, ch. 8.2 (1967)

In fact, I jumped about six inches, as if a skewer or knitting-needle had come through the seat of my chair.

Much Obliged, Jeeves, ch. 6 (1971)

getting your hooks on the thing (p. 29) *

Slang for hands; OED cites uses from 1829 on, including a 1926 tract from the Society for Pure English defining get one’s hooks on as “get hold of.”

making … heavy weather (p. 29) *

Allowing one’s emotions to be stormy; making a fuss about something. Wodehouse used Heavy Weather as the title of a 1933 Blandings Castle novel.

you follow me, Watson? (p. 29)

Only once does Sherlock Holmes pose a question in this form to Doctor Watson:

“And when I raise my hand — so — you will throw into the room what I give you to throw, and will, at the same time, raise the cry of fire. You quite follow me?”

“Entirely.”

: “A Scandal in Bohemia,” in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892)

velvet hand beneath the iron glove (p. 29) *

A humorous inversion of the usual “iron hand in a velvet glove”—ascribed to Napoleon, as in Thomas Carlyle’s “Model Prisons” (1850) in Latter-day Pamphlets.

Wodehouse used this misquotation a few other times:

“But you seemed to sense the velvet hand beneath the iron glove? No, dash it, that’s not right,” said Monty, musing.

Heavy Weather, ch. 5 (1933)

It is at moments like this that a man realizes that the only course for him to pursue, if he is to retain his self-respect, is to unship the velvet hand in the iron glove, or, rather, the other way about.

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 1 (1954)

She said it sounded as if Jeeves must be something like her father—she had never met him—Jeeves, I mean, not her father, whom of course she had met frequently—and she told me I had been quite right in displaying the velvet hand in the iron glove, or rather the other way around, isn’t it, because it never did to let oneself be bossed.

Emerald Stoker in Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 2 (1963)

over my head like the sword of — who was the chap? (p. 29)

Damocles was his name. According to legend, Damocles was a sycophant at the court of Dionysius the Elder, tyrant (i.e. ruler) of the Sicilian city of Syracuse in the 4th century BC. He so persistently praised the power and happiness of Dionysius that the tyrant ordered a banquet at which Damocles was the guest of honour but at which he found himself seated beneath a sword that was suspended from the ceiling by a single horse hair. Dionysius explained that the rank and power of the tyrant were no less precarious. The story is told by the Roman orator Cicero in his Tusculan Dispuations (Book V, 61)

the middle of the pheasant season (p. 29)

In England and Wales, the pheasant season begins on 1st October and continues until 1st February.

beetled off (p. 30) *

See Very Good, Jeeves.

ate a moody slice of cold bacon (p. 30)

See p. 22.

wins the mottled oyster (p. 30) *

Though the general idea is clear from the context, the precise meaning of this one is obscure. The phrase has not yet been found in slang dictionaries, but it is not a Wodehouse coinage; Google Books scans of the old US humor magazine Life (not the more familiar photo-journalistic magazine of the same name founded in 1936) show a 1927 usage: “I have seen many terrible college movies in my day, but this one wins the mottled oyster. It is just plain awful.” The film reviewed, The Fair Co-Ed, starred Marion Davies as “Marion Bright,” and if the rest of the writing was as formulaic as that pun on “merry and bright” one can see why the reviewer was not impressed.

Wodehouse, however, made the term famous by using it here, and by giving the name of The Mottled Oyster to a nightclub in Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit (1954) and Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin (1972). The name was adopted by a real-life bar in the Belmond Cadogan Hotel in Chelsea, London, and by a chapter of The Wodehouse Society in San Antonio, Texas.

personal effects in the dickey (p. 30)

See Summer Moonshine.

singing some light snatch (p. 30) *

A short portion of a melody or tune, an excerpt from a song.

had circumstances been different (p. 30) *

Had circumstances been different from what they were—not, of course, that they ever are—I might have derived no little enjoyment from this after-dinner saunter…

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 11 (1954)

the bowed-downer did the heart become (p. 30)

See Sam the Sudden.

the situation is a lulu (p. 31) *

The OED says that the slang term lulu is originally American for something remarkable or wonderful, often used ironically. One 1886 citation is hyphenated lu-lu; the next one, without the hyphen, is from George Ade’s Artie (1896), known to be one of Wodehouse’s sources for American colloquial speech.

start [life] as an orphan (p. 31) *

Rather a cruel wish for one’s mother, isn’t that? Not that Bertie probably thought the implications through when he said it.

“Don’t they put aunts in Turkey in sacks and drop them in the Bosphorus?” (p. 31)

An odalisque was a member of the harem, ranking below concubines and wives.

The Bosphorus is a 20-mile long strait that connects the Sea of Marmara with the Black Sea and separates the continents of Europe and Asia. It runs through the heart of Istanbul, past several Ottoman palaces, and it is said (in Brewer’s Dictionary, for example) that if the sultan wished to be rid of one of his harem, the unfortunate woman was tied in a sack and thrown into the Bosphorus.

going down for the third time in the soup (p. 31) *

The folk wisdom about “going down for three times” before drowning is debunked at The Straight Dope. (The phrase is also used with respect to a prizefighter knocked down three times, but that doesn’t seem to apply here.)

For “in the soup,” see The Inimitable Jeeves; also note p. 65 below and p. 204 below.

out pops the cloven hoof (p. 31)

eating their bread and salt (p. 31) *

In other words, as an honored guest; see Carry On, Jeeves!.

sticky (p. 32) *

See Laughing Gas.

the cat chap (p. 32)

Bertie is referring to Macbeth, who is described by his wife in such terms:

Art thou afeard

To be the same in thine own act and valour

As thou art in desire? Wouldst thou have that

Which thou esteem’st the ornament of life,

And live a coward in thine own esteem,

Letting “I dare not” wait upon “I would,”

Like the poor cat i’ the adage?

: Macbeth, Act I Scene 7

The adage referred to by Lady Macbeth is “All cats love fish but fear to wet their paws,” said of one who is anxious to obtain something of value but does not care to incur the necessary trouble or risk (Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable).

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for over twenty references to this passage.

wabble (p. 32) *

This variant form appears in US editions and original Penguin paperback plates; some UK editions substitute “wobble.” See A Damsel in Distress.

my name at Totleigh Towers is already mud (p. 32) *

In other words, his reputation with Sir Watkyn is already soiled.

a combination of Raffles and a pea-and-thimble man (p. 32)

For Raffles, see Something Fresh.

A pea-and-thimble man is a small-time con-man who makes his money by a trick that involves pushing around three thimbles, under one of which is a pea, and inviting the audience to bet on which thimble conceals the pea.

Here a little knot gathered round a pea and thimble table to watch the plucking of some unhappy greenhorn and there, another proprietor with his confederates in various disguises . . . sought by loud and noisy talk and pretended play to entrap some unwary customer, while the gentlemen confederates . . . betrayed their close interest in the concern by the anxious furtive glances they cast on all new comers.

: Nicholas Nickleby, ch. 50

Bertie is perhaps suggesting that Sir Watkyn views him as having the appearance of a gentleman and the morals of a small-time crook.

Public Enemy Number One … Two … Three (p. 32) *

According to Wikipedia, the term originated with Chicago authorities in 1930 to describe Al Capone, and was next applied to John Dillinger by the FBI in 1934. An audio interview with the FBI historian disputes that to some extent; in fact the FBI got its name only in 1935, and even when they came out with the Ten Most Wanted list in 1950 the criminals on it were not ranked or numbered.

More applicable to Wodehouse is the use in the book (originally by Wodehouse and Guy Bolton, revised by Lindsay and Crouse) and lyrics (by Cole Porter, to his own music) of the 1934 musical Anything Goes. Some of the plot complications involve the hero, Billy Crocker, being mistaken for “Snake Eyes” Johnson, Public Enemy Number One; he becomes involved with “Moonface” Martin, who is dissatisfied with his ranking of Public Enemy Number Thirteen and wants to pull off a big crime to rate higher on the list.

In Wodehouse’s 1936 novel Laughing Gas, George, one of the supposed kidnappers, has hopes to become a screenwriter, and describes his story about another Public Enemy Number Thirteen, who is superstitious about the number 13 and wants to change his ranking with a crime.

the native hue of resolution (p. 33)

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all;

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pith and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.

: Hamlet, Act III Scene 1

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for more references to this passage and a discussion of pith versus pitch. See also p. 201 below.

about the tonnage of Jessie Matthews (p. 33)

One of 11 children of a Soho costermonger, Jessie Matthews (1907–1981) was a popular musical comedy star of the 1930s. Ill-health and the onset of war put an end to her film career, but she later made a come-back as a radio performer, playing the title role in BBC’s long-running soap drama, “Mrs Dale’s Diary.”

Jessie Matthews was variously described as “gamine” and “waif-like.”

[The American first edition (Doubleday, Doran, 1938) has “about the tonnage of Maureen O’Sullivan” here. Probably best remembered as Jane to Johnny Weissmuller’s Tarzan in five films, the Irish-born actress (1911–1998) was slight (5′3″) and slender; her career was busy during the 1930s and by her own choice less intense afterward, though she continued acting in films and TV movies into the 1990s. PGW knew her in Hollywood and dedicated his 1931 novel Hot Water to her. Neither actress is mentioned in the US magazine serial. —NM]

stately home of E. (p. 34) *

See Leave It to Psmith.

Childe Roland to the dark tower came (p. 34)

Edgar:

Child Rowland to the dark tower came,

His word was still,—Fie, foh, and fum,

I smell the blood of a British man.

: King Lear, Act III Scene 4

There they stood, ranged along the hill-sides—met

To view the last of me, a living frame

For one more picture! in a sheet of flame

I saw them and I knew them all. And yet

Dauntless the slug-horn to my lips I set,

And blew. “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower came.”

: “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came” (1855)

Shakespeare is referring to an ancient Scottish ballad in which “childe Roland,” youngest brother of “fair burd Helen,” who has been taken by elves, successfully rescues his sister from Elfland. Browning’s poem is not connected with the ballad, nor is there any connection between Shakespeare “Childe Roland” and the paladin Roland of mediaeval romances.

[But Browning’s poem does cite Edgar’s mad song in Lear. Jeeves will utter the same allusion in Ch. 5 of The Mating Season, and Bertie will then later look into the history of the quotation. —NM]

rather deeply graven on my heart (p. 34) *

See Bill the Conqueror.

the sort of eye that can open an oyster at sixty paces (p. 34) *

“But watch out for Spode. He’s about eight feet high and has the sort of eye that can open an oyster at sixty paces.”

Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 2 (1963)

“She takes after my late father, a man who could open an oyster at sixty paces with a single glance.”

Galahad Threepwood speaking of Lady Constance in A Pelican at Blandings, ch. 8.2 (1969)

Sherlock Holmes … Hercule Poirot (p. 35) *

Two of the most famous detectives in literature, created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Dame Agatha Christie respectively.

a place where Man was vile (p. 35)

See Sam the Sudden.

vis-à-vis (p. 35–6)

French: face to face.

to shoot the works (p. 36)

Slang: at games of chance, to risk all on one play; hence, to make the maximum effort, to exert oneself to the fullest extent.

third waistcoat button (p. 36) *

See Thank You, Jeeves.

Chapter 3 (pp. 37–61)

a Dictator on the point of starting a purge (p. 37) *

This has to be one of the most chilling of Wodehouse’s rare mentions of tragic events in the real world. Josef Stalin’s “Great Purge” in the Soviet Union in the mid-1930s was a pretext to consolidate his power and eliminate political opposition; something on the order of a million people were executed or died in prison or exile. Although the show trials of former leaders were reported, the full extent of the purges was not known in the West at the time Wodehouse was writing, and I suspect Wodehouse would not have referred to it in a humorous book if he had known then what the world learned later.

decent habiliments (p. 37) *

Historically, this phrase refers to adequate or appropriate clothing; the earliest usage so far found is in a play, A Jovial Crew, or, the Merry Beggars by Richard Brome (1641), in which a beggar asks for money “to furnish us with linen, and some decent habiliments.”

Bertie’s reference, of course, is to the distinction between country tweeds and the more muted colors and patterns suitable for London attire. Given that his own preference was for “sprightly” check suits (see “Jeeves Takes Charge”) one wonders how outrageous old Bassett’s frightful tweeds must have been.

follows me everywhere, like Mary’s lamb (p. 38) *

See Blandings Castle and Elsewhere.

bloomer (p. 39) *

See A Damsel in Distress.

other half of the sketch (p. 39) *

Here sketch is used in its theatrical sense, as a short dramatic or comedic piece which would be one item in a revue or vaudeville show. So Bertie is referring to the married couple as the cast of a two-person playlet.

on the map (p. 40) *

On his face. See The Clicking of Cuthbert.

ewe lamb (p. 40) *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

better element (p. 40) *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

the King’s Remembrancer (p. 40)

The King’s Remembrancer was formerly an officer of the Exchequer whose primary responsibility was to collect debts owed to the sovereign. Business relating to the Exchequer was recorded in Memoranda Rolls whose name, like that of the King’s Remembrancer, reflect their memory-aiding function.

this absolute Trial of Mary Dugan (p. 41) °

The film The Trial of Mary Dugan (1929), directed by Bayard Veiller (who also wrote the 1927 Broadway play on which it was based), featured one of the stars of the silent era, Norma Shearer, in her first talking picture. Mary Dugan (Shearer), a Broadway showgirl, is accused of killing her lover, a rich playboy, by stabbing him with a knife. Dugan is defended by a lawyer friend who, however, decides not to cross-examine witnesses and later withdraws mysteriously from the case (and is finally unmasked as the real killer).

There was a re-make in 1941, directed by Norman Z. McLeod.

Neither version featured cow-creamers, baronets or would-be dictators.

thoughtfully sucking the muzzle of his gun (p. 41) *

Rather unexpected for such a forceful character as Spode. Compare the ineffectual characters Motty, Lord Pershore, in “Jeeves and the Unbidden Guest” (1917), “sucking the knob of his stick”; Eggy Mannering, in Laughing Gas, ch. 14 (1936), “sitting on the edge of a chair, sucking the knob of his stick”; and Cosmo Wisdom, in Cocktail Time, ch. 5 (1958), “nervously sucking the knob of his umbrella.”

Compare also Freddie Threepwood, who “chewed the knob of his cane” in Something New, ch. 2 (1915), and Ferdinand Dibble, who “gnawed the handle of his putter” in “The Heart of a Goof” (1923).

once lived in Arcady (p. 42)

See Something Fresh.

pancake (p. 43) *

The OED has no citations for this slang usage, but Green’s Dictionary of Slang finds 1930s examples from Damon Runyon of its use for an attractive young woman.

cut-and-thrust stuff (p. 43) *

See Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit.

telegram … telephone … post office (p. 43) *

In Britain the General Post Office was given a monopoly on telegraph communication in 1869 and a near-monopoly on telephone services by 1912. This combined setup lasted until the British Telecommunications Act 1981.

47, Charles Street, Berkeley Square (p. 44)

In In Search of Blandings, Norman Murphy notes that this was the address of Wodehouse’s friend and colleague, Ian Hay (real name John Hay Beith).

assignment re you know what (p. 44) *

Here re is legal Latin for “with regard to”–a useful abbreviation when telegraphing.

veiled woman … treaty (p. 44) *

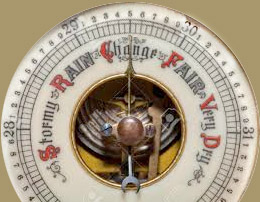

barometer … “Stormy” … “Set Fair” (p. 44) *

In most temperate climates, the barometric pressure is one fairly reliable indicator of the weather in the immediate future, so traditionally barometer dials would have these general markings as well as a numeric scale of the actual air pressure. Larger dials might have “Set Fair” between the “Fair” and “Very Dry” labels shown here.

In most temperate climates, the barometric pressure is one fairly reliable indicator of the weather in the immediate future, so traditionally barometer dials would have these general markings as well as a numeric scale of the actual air pressure. Larger dials might have “Set Fair” between the “Fair” and “Very Dry” labels shown here.

as if I were a rabbit which she was expecting shortly to turn into a gnome (p. 44) *

In Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 10, Madeline had told Bertie:

“When I was a child, I used to think that rabbits were gnomes…”

the Seigneur Geoffrey Rudel (p. 45) °

Geoffrey Rudel, a minstrel, is said to have fallen in love with Melisande, daughter of the Count of Tripoli, merely on the strength of reports of her beauty. According to the story, he set off for the East, accompanied by his friend, Bertrand d’Allamanon, but became very ill and feared that he would die without ever seeing his lady. When their ship neared land, Bertrand went ashore and hurried to ask the Countess if she would agree to come and meet her unknown lover, which she did, whereupon Rudel showed his gratitude by pegging out in front of her. No doubt taken aback by this display of gross bad manners and wishing to avoid a recurrence, Melisande hastily donned widow’s clothes and retired to a convent.

There was indeed a historical Geoffrey or Jaufré Rudel, prince of Blaye or Blaia, and “in all probability” he went on crusade in the year 1147, but apparently the other details of the legend are unsubstantiated. The story was elaborated many times in literature, including by John Graham (1836), Robert Browning, and Giosuè Carducci (1888).

cami-knickers (p. 45) *

cami-knickers (p. 45) *

A one-piece female undergarment combining a camisole and knickers, first cited in the OED in 1915. (Thanks to Stefan Nilsson for pointing us to this image.)

Even at the Drones Club, where the average of intellect is not high, it was often said of Archibald that, had his brain been constructed of silk, he would have been hard put to it to find sufficient material to make a canary a pair of cami-knickers.

“The Reverent Wooing of Archibald” (1928; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929)

p’fft (p. 46) *

The OED lists many varying forms of phut, pfft, phfft and so forth, dating from the late nineteenth century, originally onomatopoetic for a small explosion or release of air under pressure or the noise of the passage of a bullet. American gossip columnist Walter Winchell popularized it as an adjective for a failed romance or marriage; he usually spelled it phffft. In other contexts for failure, Wodehouse often uses phut:

“he made it clear all right that my allowance has gone phut again.”

Bingo Little speaking of his Uncle Mortimer in “Bingo and the Little Woman” (1922; as chs. 17–18 of The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

My closely-reasoned scheme had gone phut.

“The Rummy Affair of Old Biffy” (1924; in Carry On, Jeeves!, 1925)

But in the sense of a failed romance, Wodehouse uses p’fft once more:

I had the disquieting impression that it wouldn’t take too much to make the Stilton-Florence axis go p’fft again…

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 3 (1954)

crossword puzzle … a shrewd “Emu” (p. 46) *

See Sam the Sudden for the crossword fad in general. Wodehouse pokes gentle fun at it in many stories with frequent mentions of the sun god Ra and the flightless Australian bird Emu as simple entries in the puzzles. Only later, in Something Fishy, ch. 3 (1957) and Much Obliged, Jeeves, ch. 9 (1971), does he allude to a more modern style of cryptic puzzle clues.

parted brass rags (p. 46) °

Slang: quarrelled. See Carry On, Jeeves!.

shirty (p. 46) *

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

All Clear had been blown (p. 46) *

straight from the horse’s mouth (p. 46) *

Inside information, as if a racetrack tip were communicated by the horse itself.

hotsy-totsy (p. 46) *

See Hot Water.

his imitation of Beatrice Lillie (p. 47) °

Beatrice Lillie (1894–1989) was a Canadian-born comedienne who achieved considerable success in London and, later, New York in musical comedies and revues. A good friend of Noel Coward, she worked with him on several productions and introduced his song “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” in The Third Little Show (1932).

Beatrice Lillie (1894–1989) was a Canadian-born comedienne who achieved considerable success in London and, later, New York in musical comedies and revues. A good friend of Noel Coward, she worked with him on several productions and introduced his song “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” in The Third Little Show (1932).

During WWI, when so many men were being called to war, her slim build and short-cropped hair meant that she was often cast in male roles, something that would, no doubt, have made it easier for Catsmeat to imitate her.

[Conversely, the stout Smedley Cork in The Old Reliable (1951) would have been a less plausible imitator.]

something Jeeves had once called Gussie (p. 47) *

See Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 13.

a sensitive plant, what? (p. 47)

A Sensitive Plant in a garden grew,

And the young winds fed it with silver dew,

And it opened its fan-like leaves to the light.

And closed them beneath the kisses of Night.

: “The Sensitive Plant” (1820)

See the notes to Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 13, for more about the plant and a modern-day encounter with one.

“Oh, am I?” (p. 47) *

Bertie has obviously misheard Madeline’s reference to Shelley, thinking it to be a descriptive term like silly or surly after “you’re” rather than “your.”

mixed alcoholic stimulants (p. 48) *

See Bill the Conqueror.

all-in wrestler (p. 48) *

See The Mating Season.

vapid and irreflective observer (p. 48) *

See the notes to episode 5 of The Head of Kay’s for the literary background of this term.

sunset … reminded him of a slice of roast beef (p. 48) *

See the last note to The Matrimonial Sweepstakes for similar references elsewhere in Wodehouse.

you can’t call a girl a liar (p. 48) *

Bertie had a similar problem with Heloise Pringle in “Without the Option” (1925):

I think the girl was lying, but that didn’t make the position of affairs any better.

I wish I had a bob (p. 49) *

That is, a shilling; one-twentieth of a pound sterling. The Bank of England inflation calculator suggests a multiplication factor of 67.8 from 1939 to 2019, so this is roughly £3.40 or US$4.50 in present-day terms.

There she spouts (p. 49)

More usually rendered as “There she blows!,” this was the cry of the look-out on a whaling ship at the sight of a whale.

See also Money in the Bank.

something distinctive and individual about Gussie’s timbre (p. 50) *

Timbre is a musical term for the quality or tone color of an instrument or voice. The adjectives may be influenced by the “distinctively individual” advertising slogan for Fatima cigarettes; see Ukridge.

abaft the teapot (p. 50) *

Bertie uses a nautical term here meaning “behind, toward the rear of the vessel”; one wonders if Wodehouse picked it up at his preparatory school, which specialized in preparing boys for the Navy.

Gussie was straddling the hearthrug (p. 50) *

Compare:

Charles Augustus Pettifer took up a commanding position on the hearth rug, and stated that he was not going to see the Coronation.

“Some Reasons and a Sequel” (1902)

[Uncle Chris] straddled the hearth-rug manfully, and swelled his chest out.

Jill the Reckless/The Little Warrior, ch. 6.2 (1920)

The vicar, his hands behind his coat-tails, was striding up and down the carpet, while the bishop, his back to the fireplace, glared defiance at him from the hearth-rug.

“Mulliner’s Buck-U-Uppo” (1926; in Meet Mr. Mulliner, 1927)

The Hon. Galahad strode to the hearthrug and stood with his back to the empty fireplace. Racial instinct made him feel more authoritative in that position.

Heavy Weather, ch. 10 (1933)

And similarly:

Mrs. Cork gave her powerful shoulders a hitch, and took up her stand with her back to the empty fireplace, looking exactly like the frontispiece of her recently published volume of travel, A Woman in the Wilds, where the camera had caught her, gun in hand, with one foot on the neck of a dead giraffe.

Money in the Bank, ch. 3 (1942)

Colonel Egbert Wedge stood supporting his shoulderblades against the mantelpiece over the fireplace.

Galahad at Blandings, ch. 4 (1965)

Mussolini (p. 50)

See Summer Moonshine.

could have taken his correspondence course (p. 50) *

Others abide our question (p. 51)

Others abide our question. Thou art free.

We ask and ask—Thou smilest and art still,

Out-topping knowledge.

: “Shakespeare” (1849)

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for other allusions to Arnold’s poem.

bien-être (p. 51) *

French, “well-being”; a comfortable state.

hunky-dory (p. 51) *

American slang for “satisfactory, fine” from mid-nineteenth century; see Green’s Dictionary of Slang for a possible derivation.

given the cue (p. 52) *

Bertie is so coversant with theatrical jargon that he often applies it to everyday life.

We are as little children (p. 53)

Verily I say unto you, Except ye be converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.

Bible: Matthew 18:3

wedding breakfast (p. 53) *

certified boob (p. 54) *

A boob is a fool, a stupid or blundering person (originally US slang from early 1900s); a certified boob must be one who has been classified as such by a professional.

Man of Destiny . . . Napoleon (p. 54)

The Man of Destiny is the title of a play (1898) by George Bernard Shaw in which the young Napoleon Bonaparte finds himself entangled with a “Strange Lady.”

Saviours of Britain . . . Black Shorts (p. 54) °

Roderick Spode and his “Black Shorts” are a parody of Oswald Mosley (1896–1980), founder of the British Union of Fascists, whose members, particularly the more extremist ones, wore distinctive black shirts.

Throughout his career, Mosley showed an inability to settle within the confines of a political party. At the 1918 General Election, he won Harrow for the Conservatives, becoming the youngest MP in Parliament, but at the 1922 election, disillusioned with the Conservative Party, he contested (and won) Harrow as an Independent. Two years later, he joined the Labour Party and, after the 1929 election, served as a member of Ramsay MacDonald’s government, only to resign the following year. In 1931, he founded his own party, the New Party, but it failed to win a single seat in the 1931 election, and after meeting Mussolini in Italy, Mosley disbanded the party in 1932 and founded the British Union of Fascists. In 1936, Mosley, by now a Nazi sympathiser, married his second wife, Diana Mitford, at a ceremony which took place in the Berlin home of German propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels in front of six guests, one of them Adolf Hitler. In May 1940, Mosley and his wife were detained under Defence Regulations as persons likely “to endanger the safety of the realm” and the BUF was banned a few days later. The Mosleys were released in 1943, on grounds of his ill-health, and, though they remained in England for a few years after the war, they finally left in 1949, eventually settling in France.

On Facebook, Andrew Baker pointed out a rarely-noticed joke about the character name of Roderick Spode: “Mosley lost the 1931 election to Ida Copeland, whose husband was the owner of Spode pottery. Calling his fascist ‘Spode’ was a deep insult to Mosley.”

one of those detectives (p. 54)

This is the sort of deductive exercise at which Sherlock Holmes excels:

“It is simplicity itself,” said he; “my eyes tell me that on the inside of your left shoe, just where the firelight strikes it, the leather is scored by six almost parallel cuts. Obviously they have been caused by someone who has very carelessly scraped round the edges of the sole in order to remove crusted mud from it. Hence, you see, my double deduction that you had been out in vile weather, and that you had a particularly malignant boot-slitting specimen of the London slavey. As to your practice, if a gentleman walks into my rooms smelling of iodoform, with a black mark of nitrate of silver upon his right forefinger, and a bulge on the right side of his top-hat to show where he has secreted his stethoscope, I must be dull, indeed, if I do not pronounce him to be an active member of the medical profession.”

“A Scandal in Bohemia,” in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892)

“Beyond the obvious facts that he has at some time done manual labour, that he takes snuff, that he is a Freemason, that he has been in China, and that he has done a considerable amount of writing lately, I can deduce nothing else.”

“The Red-Headed League,” in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892)

“When a gentleman of virile appearance enters my room with such tan upon his face as an English sun could never give, and with his handkerchief in his sleeve instead of in his pocket, it is not difficult to place him. You wear a short beard, which shows that you were not a regular. You have the cut of a riding-man. As to Middlesex, your card has already shown me that you are a stockbroker from Throgmorton Street. What other regiment would you join?”

“The Adventure of the Blanched Soldier,” in The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes (1927)

Footer bags (p. 54)

Baggy knee-length shorts, as favoured by football players of that era.

Among its more social activities, the British Union of Fascists established its own football teams.

gasper (p. 55) *

A cigarette, especially an inexpensive or harsh one.

Pont Street (p. 55) *

Also the town address of Bertie’s Aunt Agatha; see Very Good, Jeeves for more on this desirable address.

a man who has found the blue bird (p. 55)

L’Oiseau bleu (1908), translated into English as The Blue Bird (1909), is a play by the Belgian author and 1911 Nobel laureate, Maurice Maeterlinck (1862–1949). It tells the story of two children, Tyltyl and Mytyl, the son and daughter of a poor woodcutter, who are sent off by the Fairy Bérylune to search the world for the Blue Bird of Happiness. After much searching, they return home to find that the Blue Bird has been in their bird-cage all the time.

From the programme for the revival of the play at London’s Haymarket Theatre in 1912: “The Blue Bird, inhabitant of the pays bleu, the fabulous blue country of our dreams, is an ancient symbol in the folk-lore of Lorraine, and stands for happiness.” Tenor Jan Peerce’s hugely popular 1945 record “The Bluebird of Happiness” served to keep the expression in the public mind.

The play has been filmed several times, twice as a silent film, in 1910 and 1918, and most famously in 1940, with Shirley Temple playing the role of Mytyl. A further film, in 1976, with Patsy Kensit as Mytyl and Elizabeth Taylor playing the part of Bérylune, was a resounding failure.

Those who make the nation’s songs (so much more admirable than its laws) advise us to look for the silver lining, to seek the Blue Bird, to put all our troubles in a great big box and sit on the lid and grin.

Bill the Conqueror, ch. 2.2 (1924)

It had a dullness, a lack of tone. It was the voice of a butler who has lost the bluebird.

“The Crime Wave at Blandings” (1936; in Lord Emsworth and Others, 1937)

That night [Bingo] dressed for dinner moodily. He was unable to discern the bluebird.

“All’s Well with Bingo” (1937; in UK edition of Eggs, Beans and Crumpets, 1940)

In that shop, on the other hand, he had given the impression of a man who has found the bluebird.

Sir Watkyn Bassett in The Code of the Woosters, ch. 3 (1938)

But, unlike him, she had not found the bluebird.

Money in the Bank, ch. 22 (1942)

“I saw no ray of hope. It looked to me as if the bluebird had thrown in the towel and formally ceased to function.”

Joy in the Morning, ch. 1 (1946)

But it takes more than that to buck a fellow up permanently who is serving an indeterminate sentence in a place like Deverill Hall, and it was not long before I was in somber mood again, trying to find the bluebird but missing it by a wide margin.

The Mating Season, ch. 7 (1949)

“The sun shining and the bluebird back once more at the old stand.”

“Jeeves Makes an Omelet” (1959; in A Few Quick Ones)

The hors d’oeuvres seem to whisper that the sun will some day shine once more, the cold salmon with tartare sauce points out that though the skies are dark, the silver lining will be along at any moment, and with the fruit salad or whatever it may be that tops off the meal, there comes a growing conviction that the bluebird, though admittedly asleep at the switch of late, has not formally gone out of business.

The Ice in the Bedroom, ch. 9 (1961)

Crispin … was wearing the unmistakable air of a man who has failed to find the bluebird.

The Girl in Blue, ch. 12.3 (1970)

a carefree cat on hot bricks (p. 55)

The idiomatic expression “like a cat on hot bricks” (in US, “on a hot tin roof”) means “uneasy, or very nervous, and unable to keep still.” Wodehouse presumably wishes us to understand that Sir Watkyn was behaving in this agitated manner, but not from any uneasiness (hence “carefree”).

See also The Girl in Blue.

clicked (p. 55) *

In this sense, been successful in his wooing; had his proposal accepted.

“I tried to muster up the nerve, but we got to Southampton without my having clicked. What a dashed difficult thing a proposal is to bring off, isn’t it!”

Eustace Hignett in Three Men and a Maid, ch. 8 (1922)

“Keep steadily before you the fact that almost anybody can get married if they only plug away at it. Look at this man Bessemer, for instance, Ronnie’s man that I told you about. As ugly a devil as you would wish to see outside the House of Commons, equipped with number sixteen feet and a face more like a walnut than anything. And yet he has clicked.”

Money for Nothing, ch. 7 (1928)

“He made his presence felt right from the beginning to an almost unbelievable extent, and actually clicked as early as the fourth day out.”

“Fate” (1931; in Young Men in Spats, 1936)

“I don’t want to shatter your dreams and all that, but are you sure you’ve clicked in that direction quite so solidly as you imagine?”

Summer Moonshine, ch. 8 (1937)

“Yes, you can start pricing wedding presents. A marriage has been arranged, and will shortly take place.”

“Good for you, Johnny, Tell me more. When did this happen?”

“Tonight. Just before I came here.”

“You really clicked, did you?”

A Pelican at Blandings, ch. 2 (1969)

hauled up her slacks about me (p. 56)

Wodehouse employs the same phrase elsewhere, though it does not seem to be in common use. From the context, it seems to mean making a special effort or employing exaggeration when describing something or someone.

As for Clarence, how easy it would be to haul up one’s slacks to practically an unlimited extent on the subject of his emotions at this time.

“The Goal-Keeper and the Plutocrat,” in The Man Upstairs

Secondly, as there appears to be no law of libel whatsoever in this great and free country, we shall be enabled to haul up our slacks with a considerable absence of restraint.

Psmith, Journalist, ch. 9

Of course, if in the vein, I might do something big in the way of oratory. I am a plain, blunt man, but I feel convinced that, given the opportunity, I should haul up my slacks to some effect.

Psmith in the City, ch. 15

He hauled up his slacks thus:

Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen, ch. 20 (1974)

See also The Inimitable Jeeves.

a cross between Robert Taylor and Einstein (p. 56)

Robert Taylor (1911–1969) was a film star and matinee-idol; nicknamed “the man with the perfect profile,” his good looks frequently secured him leading roles for which he then received unfavourable reviews from critics who could not bring themselves to accept that so handsome an actor could act.

Albert Einstein, who formulated the theory of relativity and turned classical physics on its head, needs, as they say, no introduction.

One hopes that Gussie is referring to Robert Taylor’s looks and Einstein’s brains, as the alternative hardly bears thinking about.

the full moon influences the love life (p. 57)

This is certainly true of some undersea creatures. For example, seahorses (Hippocampus spp) perform their mating rituals around the time of the full moon, while ostracods (tiny crustaceans) synchronise their mating cycles with the phases of the moon.

dumb chums (p. 57) *

In the sense of “without speech” rather than “unintelligent,” this is a frequent phrase for Wodehouse’s characters when referring to pets or other animal friends. In fact the first OED citation for “dumb chums” is from Wodehouse:

Arrived at man’s estate, he [Gussie] retired to the depths of the country and gave his life up to these dumb chums.

Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 1 (1934)

An earlier usage:

“…Our Dumb Chums’ League, of which I am perpetual vice-president”

Orlando Wotherspoon in “Open House” (1932; in Mulliner Nights, 1933)

Norman Murphy noted in A Wodehouse Handbook that the above league was clearly based on Our Dumb Friends League, an animal welfare charity founded in 1897 in London. It used a Blue Cross emblem for its fundraising campaigns, and by 1950 changed its organizational name to The Blue Cross.

And others, showing variety of species:

I can’t see why Jeeves shouldn’t go down in legend and song. Daniel did, on the strength of putting in half an hour or so in the lions’ den and leaving the dumb chums in a condition of suavity and camaraderie…

Thank You, Jeeves, ch. 18 (1934)

“This girl Dahlia’s family, you see, was one of those animal-loving families, and the house, he tells me, was just a frothing maelstrom of dumb chums. As far as the eye could reach, there were dogs scratching themselves and cats scratching the furniture. I believe, though he never met it socially, there was even a tame chimpanzee somewhere on the premises.”

A well-informed Crumpet recounting Freddie Widgeon’s tale in “Good-bye to All Cats” (1934; in Young Men in Spats, 1936)

The six Pekes accompanied [Bingo] into the library and sat waiting for their coffee-sugar, but he was too preoccupied to do the square thing by the dumb chums.

“Bingo and the Peke Crisis” (1937; in Eggs, Beans and Crumpets, 1940)

“In a nutshell, then, Aunt Hermione advised Aunt Dora to wait till Prue had popped out with the dumb chums and then go through her effects for possible compromising correspondence.”

Freddie Threepwood, speaking of his cousin taking the dogs for a walk, in Full Moon, ch. 3.6 (1947)

…in this shovel one noted what seemed to be frogs. Yes, on a closer inspection, definitely frogs. [Constable Dobbs] gave the shovel a jerk, shooting the dumb chums through the air as if he had been scattering confetti.

The Mating Season, ch. 21 (1949)

The dullest eye could perceive that the dumb chum was seriously below par, and Lord Uffenham lost no time in summoning his colleagues for a consultation.

George the bulldog in Something Fishy/The Butler Did It, ch. 20 (1957)

“I see you’re lushing up the dumb chums.”

Freddie Widgeon notes that Mr. Cornelius is giving lettuce to his rabbits in Ice in the Bedroom, ch. 1 (1961).

And note the article “Dumb Chums at Riverhead” (Punch, September 7, 1955) about a man who raised armadillos.

like a Pekingese taking a pill (p. 57)

Wodehouse is, no doubt, writing here from personal experience: Pekingese were their favourite dogs and even in Berlin, after Wodehouse was released from internment and Ethel joined him, she was accompanied by their Pekingese, Wonder.

out of the night that covered me (p. 58)

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the Pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

: “Invictus” (1875)

He eats a lot of fish (p. 59) *

See Very Good, Jeeves for a discussion of this topic.

I played on you as on a lot of stringed instruments (p. 59) *

safely under the wire (p. 60) *

That is, safely married; a figurative allusion to the imaginary wire across the finish line of a horse-racing track.

hunting newts in Africa (p. 60) *

Bertie’s adaptation for Gussie of the usual rejected suitor’s trip to shoot grizzly bears in the Rocky Mountains; see A Damsel in Distress.

Chapter 4 (pp. 62–86)

as you jog along (p. 62) *

In recent years, the verb jog has so often been used for running at a moderate pace for aerobic exercise that we tend to forget its original senses. Transitively, to jog something meant to shake it up, give it a jerky push or nudge. Intransitively, to jog was to move unsteadily or as if shaken, “to move with small shocks like those of a low trot” (Samuel Johnson). So Bertie’s usage here is less like a smooth trip around a fitness track and more like being jolted continually through life by random events.

leap . . . like a gaffed salmon (p. 62)

Lord Emsworth … leaped on his settee like a gaffed trout.

Heavy Weather, ch. 17 (1933)

He had been sitting hard by, staring at the ceiling, and he now gave a sharp leap like a gaffed salmon and upset a small table containing a vase, a bowl of potpourri, two china dogs, and a copy of Omar Kháyyám bound in limp leather.

Tuppy in Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 14 (1934)

Bingo, who had given a sharp, convulsive leap like a gaffed salmon, reassembled himself.

“The Editor Regrets,” in Eggs, Beans and Crumpets (1940)

It caused Lord Shortlands to leap like a gaffed salmon and Terry to quiver all over.

Spring Fever, ch. 14 (1948)

A gaff is a hook used to land large fish; because a gaffed fish is not dead, it will usually writhe convulsively.

private school (p. 62) *

The distinction between private and public schools in Britain at this era was not the same as in modern American usage. Neither was government-run, like the American public school system. (Government-run schools in Britain had other names such as state school or council school.) A British public school, like Eton, Harrow, or Wodehouse’s alma mater Dulwich, was chartered as an institution for public benefit, with an endowment and a board of trustees or governors; in the USA it would be classified as a nonprofit organization. A private school in Britain meant one that was privately owned and operated as a commercial venture; typically the headmaster and the proprietor would be the same person. Thus any money not spent on feeding the students would mean more in the headmaster’s pocket, so it was no wonder that Bertie was attracted by the possibility of a late-night biscuit.

biscuits (p. 62) *

Even in the US first edition book, Bertie uses the British term for what Americans would call cookies. (The first three paragraphs of chapter 4 are omitted in the SEP serialization.)

bounder (p. 62) *

See Bill the Conqueror.

sang-froid (p. 62) *

French, literally “cold blood”; figuratively, calmness.

map (p. 62) *

As with p. 119 below, see The Clicking of Cuthbert.

élan and espièglerie (p. 63)

French: élan — impetuosity, dash; espièglerie — frolicsomeness.

All right up to the neck, but from there on pure concrete (p. 63) *

See Very Good, Jeeves.

gumboils (p. 63) *

See The Mating Season.

the Scotch express (p. 63) *

Man as Nature’s last word (p. 63) *

For instance:

…if man be the highest object submitted to direct study, it is in man, and man in his highest capacities, functions, and employments, that we find Nature’s last word and most important revelation.

Patrick Edward Dove: The Logic of the Christian Faith (1856)

The phrase is used again in ch. 11, p. 195.

full many a glorious morning (p. 63)

Full many a glorious morning have I seen

Flatter the mountain-tops with sovereign eye,

Kissing with golden face the meadows green,

Gilding pale streams with heavenly alchemy;

Anon permit the basest clouds to ride

With ugly rack on his celestial face,

And from the forlorn world his visage hide,

Stealing unseen to west with this disgrace:

Even so my sun one early morn did shine

With all triumphant splendor on my brow;

But out, alack! he was but one hour mine;

The region cloud hath mask’d him from me now.

Yet him for this my love no whit disdaineth;

Suns of the world may stain when heaven’s sun staineth.

: Sonnet XXXIII

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for other references to this sonnet.

put the bee on (p. 64) *

A slang phrase with varying derivations and meanings. Wodehouse uses it in the sense of quash, finish off:

this development absolutely put the bee on the wedding. Everybody sympathized with Claude and said it was out of the question that he could dream of getting married.

“No Wedding Bells for Him” (1923; in Ukridge, 1924)

the old boy most fortunately got the idea that I was off my rocker and put the bee on the proceedings.

“Without the Option” (1925; in Carry On, Jeeves!, 1925/27)

Yes, all the love which I had lavished on this girl two years ago and which I had supposed her crisp remarks at Cannes had put the bee on for good was working away at the old stand once more, as vigorously as ever.

Laughing Gas, ch. 23 (1936)

I put the bee on this suggestion with the greatest promptitude.

Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 24 (1963)

Green’s Dictionary of Slang derives this sense of bee from the initial letter of “bag” as in the phrase “put the bag on” meaning to halt or interfere with. This sense is distinguished from another initial-letter abbreviation of put the bite on (with a play on bee as something that stings) meaning to blackmail, to extort, to press for a loan.

“I’m in the soup.”

“Up to the thorax.” (p. 64) *

For “in the soup,” and some of its variants, see The Inimitable Jeeves; also note p. 31 above and p. 204 below.