Big Money

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

This is part of an ongoing effort by the contributors to Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums to document references, allusions, quotations, etc. in the works of P. G. Wodehouse. These notes, a work in progress, are by Neil Midkiff, with contributions from others as noted below.

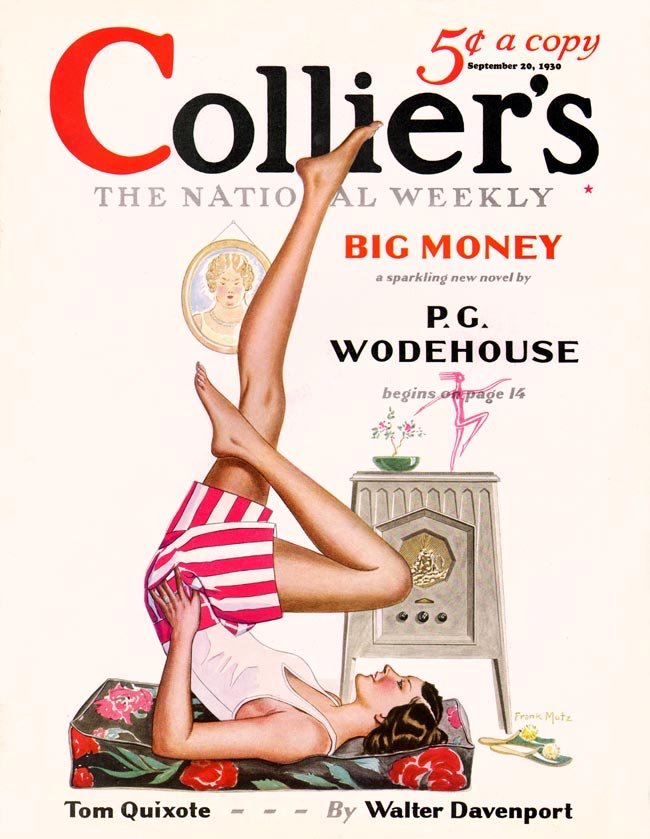

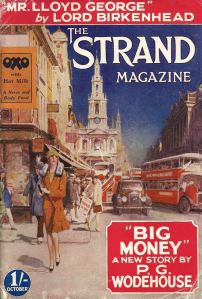

The novel initially appeared as a serial in

Collier’s and the Strand magazine; see this page for dates and details.

The novel initially appeared as a serial in

Collier’s and the Strand magazine; see this page for dates and details.

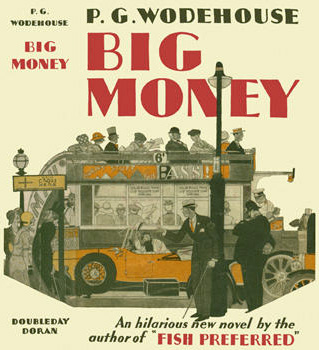

The first US hardcover edition was issued by Doubleday, Doran & Co., New York, on 30 January 1931; the UK edition was issued by Herbert Jenkins Ltd. on 20 March 1931.

The first US hardcover edition was issued by Doubleday, Doran & Co., New York, on 30 January 1931; the UK edition was issued by Herbert Jenkins Ltd. on 20 March 1931.

Page references below refer to the 1973 Penguin paperback, in which the text runs from pages 5 to [240]. For users of other editions, a table of correspondences between the pagination of several available editions will open in a new browser tab or window upon clicking this link.

|

Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 |

Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 |

Chapter 1

Drones Club in Dover Street (p. 5)

Godfrey, Lord Biskerton (p. 5)

As the firstborn son of an earl, Godfrey has a courtesy title, one of his father’s subsidiary titles, which gives him status but no actual rights. He is presumably a viscount (compare Lord Bosham) but this is not explicitly mentioned in this book.

the City … Cornhill (p. 5)

Here the City is a metonym for London’s financial district, as opposed to its use for the historic Roman settlement and the present-day local government body with its own Lord Mayor (all roughly coterminous). The Bank of England and the original Royal Exchange site are at the corner of Cornhill and Threadneedle Street in the City.

performing fleas (p. 5)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

strayed from the fold (p. 5)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

scenario (p. 5)

See Sam the Sudden.

as close as the paper on the wall (p. 5)

sermon on Brotherly Love (p. 5)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

“Why, in the days when I was with him, old Heppenstall never used to preach under half an hour, and there was one sermon of his on Brotherly Love which lasted forty-five minutes if it lasted a second.”

“The Great Sermon Handicap” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

With a little sigh of rapture, Anselm cleared his throat and gave out the simple text of Brotherly Love.

“Anselm Gets His Chance” (1937; in Eggs, Beans and Crumpets, 1940)

the summer Peanut Brittle won the Jubilee Handicap (p. 5)

Here a racehorse is named Peanut Brittle after a typically American confection with salted peanuts embedded in a thin layer of hard-cooked caramel candy, broken into chunks after cooling.

Soon, perhaps because he was an unquenchable optimist, but more probably because it was his job, he would patrol the train offering for sale the peanut brittle and the road maps of Long Island which nobody ever bought.

On the Long Island Rail Road in Uneasy Money, ch. 25 (US version only, 1916)

The Jubilee Handicap was once the name of a prestigious horse race run on a one-mile course at Kempton Park, begun in the late 19th century and renamed for commercial reasons in 2000; the flat course has been abandoned in favor of a synthetic track in recent years and is now overgrown.

Wodehouse was fond of using constructions such as the quotation above to give his fiction a sense of historicity without naming a specific year. Typically the winning horse is fictional but the race was a real one.

She married my Uncle Thomas—between ourselves a bit of a squirt—the year Bluebottle won the Cambridgeshire…

“Clustering Round Young Bingo” (1925; in Carry On, Jeeves, 1925)

“Believe me, Muriel, if you can really get seven to two, you are onto the best thing since Buttercup won the Lincolnshire.”

“The Reverent Wooing of Archibald” (1928; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking)

“It was at Ascot, the year Martingale won the Gold Cup . . .”

Summer Lightning, ch. 19 (1929)

She married old Tom Travers the year Bluebottle won the Cambridgeshire, and is one of the best.

“Jeeves and the Song of Songs” (1929; in Very Good, Jeeves, 1930)

In the autumn of the year in which Yorkshire Pudding won the Manchester November Handicap, the fortunes of my old pal Richard (‘Bingo’) Little seemed to have reached their—what’s the word I want? He was, to all appearances, absolutely on plush.

“Jeeves and the Old School Chum” (1930; in Very Good, Jeeves, 1930)

She is the one, if you remember, who married old Tom Travers en secondes noces, as I believe the expression is, the year Bluebottle won the Cambridgeshire, and once induced me to write an article on What the Well-Dressed Man is Wearing for that paper she runs—Milady’s Boudoir.

Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 4 (1934)

“You remind me of my little boy Percy, who took the knock the year Worcester Sauce won the Jubilee Handicap.”

“All’s Well with Bingo” (1937; in Eggs, Beans and Crumpets, UK edition, 1937)

Gally, who had been comparing Freddie to his disadvantage with a half-witted whelk-seller whom he had met at Hurst Park the year Sandringham won the Jubilee Cup, stopped in mid-sentence.

Full Moon, ch. 9.1 (1947)

Add brother Lancelot, who got jugged for passing bad cheques the year Hot Ginger won the Cesarewitch, and the roster of Monty’s connections was complete.

Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin, ch. 11 (1972)

He made but one exception, the sixth Earl, who he said reminded him of a charming pea and thimble man with whom he had formed a friendship one afternoon at Hurst Park race course the year Billy Buttons won the Jubilee Cup.

Sunset at Blandings, ch. 4 (1977)

the luck of the Conways (p. 6)

Wodehouse titled a 1933 short story “The Luck of the Stiffhams” (collected in Young Men in Spats, 1936), but this was just the beginning of a series of references to inherited good fortune, including the title of his 1935 novel The Luck of the Bodkins.

It was too late to back out now, and he watched the proceedings with a bulging eye, fully cognizant of the fact that all that stood between him and a very sticky finish was the luck of the Stiffhams.

“The Luck of the Stiffhams” (1933; in Young Men in Spats, 1936)

However, the luck of the Widgeons saw them through and eventually they came, still afloat, to the unfrequented upper portions of the stream.

“Trouble Down at Tudsleigh” (1935; in Young Men in Spats, UK edition, 1936, and in Eggs, Beans and Crumpets, US edition, 1940)

“Only the luck of the Littles saved him from taking a toss which threatened to jar his fat trouser seat clean out of the editorial chair, never to return.”

The Crumpet speaking of Bingo Little in “The Editor Regrets” (1939; in Eggs, Beans and Crumpets, 1940)

The luck of the Duffs, he felt, was in the ascendant.

Quick Service, ch. 10 (1940)

“The luck of the Widgeons has turned, and affluence stares me in the eyeball.”

Freddie in Ice in the Bedroom, ch. 1 (1961)

A man of liberal views, he had no objection whatsoever to a little gentlemanly blackmail, and here, you would have said, the luck of the Dunstables had handed him the most admirable opportunity for such blackmail.

Service with a Smile, ch. 7 (1961)

“On no account to allow yourself to be alone with the female whom, but for the luck of the Emsworths, you might have married twenty years ago.”

Gally to Clarence in Galahad at Blandings, ch. 10.3 (1965)

In the final issue the luck of the Stickneys had held.

Company for Henry/The Purloined Paperweight, ch. 3.3 (1967)

fingered his bread (p. 6)

A sign of nervousness or embarrassment.

It was one of those jolly, happy, bread-crumbling parties where you cough twice before you speak, and then decide not to say it after all.

“The Aunt and the Sluggard” (1916; in Carry On, Jeeves, 1925)

His wife crumbled bread.

Alice, Mrs. Reggie Byng, in A Damsel in Distress, ch. 21 (1919)

Wally crumbled his roll.

Jill the Reckless/The Little Warrior, ch. 15.2 (1920)

Mr. Hammond crumbled his bread.

Bill the Conqueror, ch. 17.3 (1924)

He gave a groan and began to crumble my bread.

“The Letter of the Law” (1936; in Lord Emsworth and Others, 1937)

There was none of this sort of thing about Madeline Bassett and Gussie. He looked pale and corpselike, she cold and proud and aloof. They put in the time for the most part making bread pills and, as far as I was able to ascertain, didn’t exchange a word from start to finish.

The Code of the Woosters, ch. 6 (1938)

Sitting next to Florence, who spoke little, merely looking cold and proud and making bread pills, I had ample leisure for thought during the festivities, and by the time the coffee came round I had formed my plans and perfected my strategy.

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 11 (1954)

‘At dinner last night I noticed that he was refusing Anatole’s best, while she looked wan and saintlike and crumbled bread.’

Aunt Dahlia speaking of Spode and Madeline in Much Obliged, Jeeves, ch. 9 (1971)

Vicky was pale and cold, and Jeff crumbled a good deal of bread.

Sunset at Blandings, ch. 11 (1977)

Valley Fields (p. 6)

See Sam the Sudden.

old family retainer (p. 6)

Many of the young men in Wodehouse’s stories find themselves oppressed by old nurses as well as by landladies with overly motherly interference.

J. Willoughby Braddock in Sam the Sudden (1925) is supervised by his former nurse Martha Lippett, who still calls him Master Willie.

Frederick Mulliner in “Portrait of a Disciplinarian” (1927) feels the old commanding nature of Nurse Wilks.

Berry Conway in the present book is fussed over by his former nurse Hannah Wisdom.

Lord Droitwich in If I Were You (1931) finds himself in an awkward position due to the interference of “Ma” Price.

Jeff Miller in Money in the Bank (1942) and John Halliday in A Pelican at Blandings (1969) each have Ma Balsam as an inquisitive and interfering landlady at Halsey Chambers, Mayfair.

Bingo Little’s childhood faults are recalled by his former nannie Sarah Byles, nurse to young Algernon Little in “The Shadow Passes” (1950).

Cosmo Wisdom in Cocktail Time (1958) hears nothing but gloom from his landlady, Mrs. Keating.

Johnny Pearce in Cocktail Time (1958) is trying to get rid of his onetime nurse Nannie Bruce, but lacks the cash to pension her off.

warm woolies (p. 6)

One suspects that those in charge of the young Wodehouse had similarly over-emphasized the need for winter underwear.

He forgot those sad, solitary wanderings of his in the bushes at the bottom of the garden; he forgot that his mother had bought him a new set of winter woollies which felt like horsehair; he forgot that for the last few evenings his arrowroot had tasted rummy.

Also three further mentions in “The Awakening of Rollo Podmarsh” (1923; in The Heart of a Goof, 1926)

“A fair, sunny day, made gracious by a temperate westerly breeze. And yet, Mulliner, if you will credit my statement, my wife insisted on my putting on my thick winter woollies this morning. … They are made of thick flannel, and I have an exceptionally sensitive skin.”

The Bishop of Stortford in “Mulliner’s Buck-U-Uppo” (1926; in Meet Mr. Mulliner, 1927/28)

Pongo’s face became mask-like and a thin coating of ice seemed to form around him. A more sensitive man than Lord Ickenham would have sent for his winter woollies.

Uncle Dynamite, ch. 2 (1948)

I could also do with a case of champagne and some warm winter woollies.

Over Seventy, ch. 6.3 (1957)

“Yay?” he said, hoping that his loved one had not summoned him to tell him he must wear his thick woollies. She had a way of doing so when the English summer was on the chilly side, and they tickled him.

Gordon Carlisle in Cocktail Time, ch. 6 [and three more references in following chapters] (1958)

“He stresses that the air there has quite a nip to it. Frost, snow and ice bound, and the man who hasn’t his winter woollies is out of luck.”

Quoting Robert W. Service on the Yukon in Frozen Assets/Biffen’s Millions, ch. 7.1 (1964)

A tear was stealing down Sally’s cheek, and crying women always made him feel as if he were wearing winter woollies during a heat wave.

Bachelors Anonymous, ch. 5.3 (1973)

‘I fail to understand you,’ he said, his voice and manner so chilly that Plank must have been wishing he was wearing his winter woollies.

Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen, ch. 19 (1974)

financier (p. 6)

See Piccadilly Jim.

I learned shorthand (p. 6)

Wodehouse refers to stenography so often that one wonders if he had tried to learn it as a youth or had been recommended to do so, though surely it was not taught on the Classical side at Dulwich College. No sign of shorthand is evident in any of the Wodehouse manuscripts or corrected typescripts that I have seen reproduced.

He also mentions his disinclination to dictate his fiction to a stenographer (for instance, the preface to the 1975 edition of Thank You, Jeeves, quoted below), and this is paralleled by Corky’s account of trying to dictate to Dora Mason in “Ukridge Sees Her Through” (1923; in Ukridge, 1924). In any event, shorthand and stenographers are common in his fiction.

See also Carry On, Jeeves.

“I went to four private schools before I started on the public schools. My pater took me away from the first two because he thought the drains were bad, the third because they wouldn’t teach me shorthand, and the fourth because he didn’t like the headmaster’s face.”

Farnie in A Prefect’s Uncle, ch. 3 (1903)

All she demanded from New York for the present was that it should pay her a living wage, and to that end, having studied by stealth typewriting and shorthand, she had taken the plunge, thrilling with excitement and the romance of things; and New York had looked at her, raised its eyebrows, and looked away again.

Mary Hill in “Three from Dunsterville” (1911; in The Man Upstairs, 1914)

“There must be something,” continued Mrs. Oakley. “When I was your age I had taught myself bookkeeping, shorthand, and typewriting.”

The Prince and Betty, ch. 11 (US edition, 1912)

When he sank back in his chair, speechless and exhausted like a Marathon runner who has started his sprint a mile or two too soon, it was Miss Pillenger’s task to unscramble her shorthand notes, type them neatly, and place them in their special drawer in the desk.

“A Sea of Troubles” (1914; in The Man with Two Left Feet, 1917)

“My downfall began when I joined the Yonkers Short-Hand and Typewriting Correspondence College.”

“My Battle with Drink” (1915)

If James Renshaw Boyd had been her brother Jack—now in mid-Atlantic, painfully trying to take down shorthand notes from dictation without being sea-sick—she could not have felt more perfectly safe.

“Black for Luck” (1915; UK magazine version only)

“I was a stenographer in the house that published his songs when I first met him.”

Billie Dore on George Bevan in A Damsel in Distress, ch. 1.2 (1919)

George was employed at the offices of a magazine which dictated the fashions to a million women, where even the shorthand-writers looked like fashion-plates and every caller presented to his gaze the last word in what was smart.

“The Spring Frock” (1919)

Mr. McHoots ran through a dozen of the basic rules, and I took them down in shorthand.

“The Heel of Achilles” (1921; in The Clicking of Cuthbert, 1922)

“I’m pretty good at typing and I can do a sort of shorthand.”

Flick Sheridan in Bill the Conqueror, ch. 7 (1924)

“I’ve got a job as stenographer at the London branch of the Paradene Pulp and Paper Company.”

Flick Sheridan in Bill the Conqueror, ch. 9.1 (1924)

“Last Wednesday I observed you kissing my stenographer.”

“The poor little thing had toothache.”

Sam the Sudden/Sam in the Suburbs, ch. 1 (1925)

“It’s more a matter with him of having somebody to keep his papers in order and all that sort of thing, so typing and shorthand are not essential. You can’t do shorthand, I suppose?”

“I don’t know. I’ve never tried.”

“A Bit of Luck for Mabel” (1925; in Eggs, Beans and Crumpets, 1940)

The exact words of my harangue have, I am sorry to say, escaped my memory. It is a pity that there was nobody taking them down in shorthand, for I am not exaggerating when I say that I surpassed myself.

The Code of the Woosters, ch. 13 (1938)

Life at Tost would have been a very different thing without them, and I take off my hat to Professor Doyle-Davison and the other unselfish men who gave up so much time to educating and amusing us. Thanks to them it was possible for an internee to learn French, German, Dutch, Spanish, Italian, English literature, French literature, shorthand, first aid, seamanship and the rudiments of medicine.

“My Year Behind Barbed Wire” (Cosmopolitan, October 1941)

…between us we must have a hundred unpublished yarns about Erlanger, Savage etc. Do you think in your spare time you could dictate a few to a stenographer – quite in the rough, just the main points for me to work up?

Letter to Guy Bolton about what would be Bring On the Girls, 21 January 1946, in Yours, Plum (ed. Frances Donaldson, 1990)

Connie was always encouraging ghastly spectacled young men with knobbly foreheads and a knowledge of shorthand to infest the castle and make life a burden to him, but there had been such a long interval since the departure of the latest of these that he was hoping the disease had run its course.

Lord Emsworth on his secretaries in Pigs Have Wings, ch. 2.1 (1952)

‘I seen in a minute he was our oyster,’ Mr. Lehman would have said, if he had been dictating his Memoirs to a stenographer.

Barmy in Wonderland, ch. 9 (1952)

Barmy turned to Dinty, as brisk as ever.

“Can you do shorthand?”

“The shorter it is, the better I like it.”

Barmy in Wonderland, ch. 21 (1952)

“To which her reply”—she consulted a shorthand note in her notebook—“was ‘My dear Alaric!’ indicating that she was not prepare-ahed to consid-ah the ide-ah.”

Lavender Briggs in Service with a Smile, ch. 5.1 (1961)

“Because you’ve got the whole thing wrong, though I must say the way you’ve managed to record the dialogue does you a good deal of credit. Do you use shorthand?”

Bertie to Lord Sidcup in Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 18 (1963)

Gally enlivened their progress with the story of the girl who said to her betrothed, “I will not be dictated to!” and then went and got a job as a stenographer, while Lord Emsworth, who never listened to stories and very seldom to anything else, continued to explain why he found Sandy Callender such a thorn in the flesh.

Galahad at Blandings, ch. 6.1 (1965)

“When he died, I was brought up by an aunt and learned shorthand and typing, and here I am.”

Dinah Biddle in “Life with Freddie” (in Plum Pie, 1966/67)

“I had always wanted to be a secretary, so I boned up on shorthand and efficiency and all that, and I got a job, then a better job, till climbing the ladder rung by rung I got taken on by Polk Enterprises, finally, as told in an earlier chapter, becoming J. B. Polk’s confidential secretary.”

Vanessa Polk in A Pelican at Blandings, ch. 11.3 (1969)

“Boko dictates his stuff, and he said she was tops as a shorthand typist.”

Magnolia Glendennon in Much Obliged, Jeeves, ch. 3 (1971)

It is one thing to take down letters in shorthand, with her skill at which he had long been familiar, and quite another to raid your employer’s frigidaire for Bavarian cream after dark.

Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin, ch. 5.2 (1972)

Not that I ever thought of dictating it to a stenographer. How anybody can compose a story by word of mouth, face to face with a bored looking secretary with a notebook is more than I can imagine.

Preface to the 1975 Barrie & Jenkins reprint of Thank You, Jeeves

two hundred pounds (p. 7)

To account for inflation from 1930 (when this novel was written and serialized) to 2024, measuringworth.com suggests a present-day equivalent value of roughly £17,000 or US$22,500.

twopenny jam sandwich (p. 7)

Guessing that school days were ten years prior, 2d in 1920 would have a modern-day purchasing power of roughly £0.43 or 57 cents US.

only child (p. 7)

Others referred to as an only child include Isabel Rackstraw in “The Goal-Keeper and the Plutocrat” (1912), young Peter in the second story told by The Mixer (1915), Alexander Worple’s baby in “The Artistic Career of Corky”/“Leave It to Jeeves” (1916), Braid Vardon Bates in “Jane Gets Off the Fairway” (1924), Molly Waddington in The Small Bachelor (1926), Veronica Wedge in Full Moon (1947), and Gertrude Winkworth in The Mating Season (1949).

a bit of a blister (p. 7)

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

the jute business (p. 7)

See Carry On, Jeeves.

velvet suit (p. 8)

A probable allusion to Little Lord Fauntleroy; see Uncle Fred in the Springtime. Compare the first quotation under long golden curls, next.

long golden curls (p. 8)

“Have you forgotten that Charlie Field wore velvet Lord Fauntleroy suits and long golden curls?”

Jill the Reckless/The Little Warrior, ch. 2.2 (1920)

“I don’t know why it is, but I’ve never been able to bear with fortitude anything in the shape of a kid with golden curls.”

Bertie on Sebastian Moon in “Jeeves and the Love that Purifies” (1929; in Very Good, Jeeves, 1930)

I mean to say, life’s difficult enough as it is. You don’t want to aggravate the general complexity of things by getting changed into a kid with knickerbockers and golden curls.

Laughing Gas, ch. 7 (1936)

halcyon years (p. 8)

A time of calmness, peace, prosperity, or pleasant weather. From a mythological bird said to nest upon the sea during midwinter, “charming the wind and waves into calm” [OED].

inked darts (p. 8)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

getting gold out of sea-water (p. 8)

It has been recognized since at least the eighteenth century that traces of gold can be found in natural waters, and an 1873 scientific paper was widely circulated and quoted. The concentration, though, is so small that the energy required to extract it costs more than the value of the gold recovered.

The thing began to bore Mr. Scobell. He left the conduct of the journal more and more to Mr. Renshaw, until finally—it was just after the idea for extracting gold from sea water had struck him—he put the whole business definitely out of his mind.

The Prince and Betty, ch. 12 (US version, 1912)

“I wonder if I could interest you in a block of Atlantic Ocean Ordinaries? It is a company formed for the purpose of extracting gold from sea water, and I need scarcely tell you that its possibilities are boundless.”

Jasper Biffen in “Big Business” (US magazine version, 1952)

“I wonder,” he said, “if instead of a cheque for that sum young Mulliner would not prefer a block of Deep Blue Atlantic stock of equivalent value? It is a company formed for the purpose of extracting gold from sea water, and its possibilities are boundless.”

Sir Jasper Todd in “Big Business” (rewritten for A Few Quick Ones, 1959)

“And if it wasn’t a play, it would be some scheme for getting gold out of sea water.”

Company for Henry, ch. 5 (1967)

Mugs (p. 8)

A mug is a gullible simpleton, a person easily persuaded or taken advantage of (British slang, mid-nineteenth century).

scaly (p. 9)

Attwater (p. 9)

Probably unrelated to other Attwaters in Wodehouse’s fiction: Roland Moresby Attwater in “Something Squishy” (1924) and “The Awful Gladness of the Mater” (1925), and the family in Summer Moonshine (1937) of J. B. Attwater, proprietor of the Goose and Gander, along with his son Cyril who delivers messages and his brother’s daughter who fills in as barmaid.

an eye like a haddock (p. 9)

Found only in one other Wodehouse character:

Professor Pringle was a thinnish, baldish, dyspeptic-lookingish cove with an eye like a haddock, while Mrs. Pringle’s aspect was that of one who had had bad news round about the year 1900 and never really got over it.

“Without the Option” (1925; in Carry On, Jeeves, 1925)

face like teak (p. 9)

Compare:

Much voyaging on the high seas had given Hash’s cheeks the consistency of teak, but at this point something resembling a blush played about them.

Sam the Sudden/Sam in the Suburbs, ch. 16.2 (1925)

This one, whose name was McTeague, and who had spent many lively years in the army before retiring to take up his present duties, had a grim face made of some hard kind of wood and the muscles of a village blacksmith.

Summer Lightning, ch. 4.3 (1929)

Import and Export business (p. 9)

This line of work pops up frequently in Wodehouse. One wonders whether it was used as a convenient form of business that would not require much research of details, as would something like the pulp and paper business in Bill the Conqueror.

The reason for the activity prevailing on the tenth floor of the Wilmot was that a sporting event of the first magnitude was being pulled off there—Spike Delaney, of the John B. Pynsent Export and Import Company, being in the act of contesting the final of the Office Boys’ High-Kicking Championship against a willowy youth from the Consolidated Eyebrow Tweezer and Nail File Corporation.

Sam the Sudden/Sam in the Suburbs, ch. 1 (1925)

“Her blighted father, to wit, J. G. Butterwick, of Butterwick, Price, and Mandelbaum, export and import merchants.”

Heavy Weather, ch. 5 (1933); Butterwick pops up in several later books as well.

The most recent attempt on his part to do something about poor Cossie had been to secure him a post in the export and import firm of Boots and Brewer of St. Mary Axe, and the letter his sister was reducing to pulp announced, he presumed, that Boots and Brewer had realized that the only way of making a success of importing and exporting was to get rid of him.

Cosmo Wisdom in Cocktail Time, ch. 3 (1958)

“And I was just telling her how the sales of the Paramount in New York State compared with those in Illinois, when she suddenly turned on me like a tigress and shouted: ‘You and your darned old hams! and swept off and married Otis Chavender, Import and Export. Thank God!” said Mr Duff piously.

Quick Service, ch. 2 (1940)

‘And he said you’d got to go into his business.’

‘Yes. Import and export, if that means anything to you.’

‘It doesn’t.’

‘It didn’t mean much to me, and I wasn’t eager to learn more.’

Jane Martyn and Bill Hardy in Company for Henry, ch. 7.3 (1967)

own my poor black body (p. 9)

Though this sounds like a quotation from an African-American spiritual, no other source of this phrase is found in a Google Books search. The comparison of office drudgery to historical slavery would not pass today’s tests of sensitivity, but Conway’s reference seems to me to be one of sympathy rather than minimization of wrongs. [NM]

to buzz off round the world on a tramp steamer (p. 9)

The urge felt by several of Wodehouse’s characters to do this can be traced to Plum’s Dulwich study-mate Bill Townend; see Wodehouse’s Introduction to Townend’s The Ship in the Swamp (1928), and the letter to Townend dated November 20, 1924, in Author! Author! (1962) in which Plum asked Bill several technical questions about tramp steamer travel, dress onboard ship, and so forth.

Toward the end of that wonderful summer of 1906, discouraged by my failure as an artist, I felt that I needed a new source of material for my pictures, though actually what I needed was talent. Someone suggested that I should go for a voyage in a tramp steamer. Plum said that if I really wanted to go—“and rather you than me”—he would pay my expenses.

Townend’s Introduction to Performing Flea (1953)

Berry Conway in the present novel has not yet gone to sea. Other Wodehouse characters have:

“You remember the Hyacinth, the tramp steamer I took that trip on a couple of years ago.”

Ukridge in “The Debut of Battling Billson” (1923; in Ukridge, 1924)

“Corky, old horse, I have travelled all over the world in tramp steamers and what not.”

Ukridge in “Buttercup Day” (1925; in Eggs, Beans and Crumpets, 1940)

“Hash Todhunter, you know, the cook of the Araminta. You remember I took a trip a year ago on a tramp steamer? This fellow was the cook.”

Sam the Sudden/Sam in the Suburbs, ch. 1, the first of many references to Sam Shotter’s travels (1925)

“The last I heard of you, you were a sailor on a tramp steamer.”

The Princess Dwornitzchek to Joe Vanringham in Summer Moonshine, ch. 20 (1937)

See also Bill the Conqueror for Wodehouse quotations about the sort of language and behavior expected of the second mate on a tramp steamer. And see the early story “How Kid Brady Took a Sea Voyage” (1907) for an account of the hero being shanghaied onto a “hell ship” which must also owe much to Townend’s seagoing experience.

old bag (p. 9)

This term of endearment has not been found elsewhere in Wodehouse; the USA edition has old boy here, and one is tempted to speculate a typographical error in the UK editions at this point. Lord Biskerton calls Berry “old boy” about twenty other times in this novel, including twice in his next speech paragraph.

I’m broke. My gov’nor’s broke. (p. 10)

Among members of the aristocracy in Wodehouse whose family fortunes prove to be insufficient:

• Lord Arthur Hayling in the UK editions of The Prince and Betty is a fortune-hunting suitor to both Della Morrison and Betty Silver.

• Lord Evenwood cannot settle money on his daughter Lady Eva to allow her to marry a poor relation in “The Episode of the Hired Past”, because of land taxes and the expense of keeping up the family estate.

• Bill, Lord Dawlish, in Uneasy Money has “that most ironical thing, a moneyless title.”

• Algie, Lord Wetherby, is a penniless Earl in Uneasy Money.

• Marmaduke, Lord Chuffnell, in Thank You, Jeeves, cannot afford to renovate Chuffnell Hall in order to sell it.

• Lord Uffenham can’t keep up Shipley Hall on his income, and rents it to Clarissa Cork in Money in the Bank and to Roscoe Bunyan in Something Fishy.

• Lord Shortlands in Spring Fever wants to marry his cook but can’t afford to do so.

• Bill Belfrey, Lord Rowcester/Towcester in Ring for Jeeves/The Return of Jeeves “can’t afford to run a castle on a cottage income.”

relict (p. 10)

Survivor, widow; a historical term now mostly in formal or mock-formal use. The OED cites Wodehouse’s use in The Small Bachelor, ch. 2 (1926/27).

C.V.O. (p. 10)

Commander of the Royal Victorian Order, an honour established by Queen Victoria in 1896 which recognizes personal service to the royal family. Commander is the middle in rank of the five grades of the order, granting the right to use the initials after one’s name, but not including the prefix of Sir or Dame, which are only for the upper two grades of the order.

Lazarus in person (p. 10)

Not the Lazarus of Bethany, raised from the dead in chapter 11 of the Gospel of John, but rather the poor man Lazarus of Luke 16:19–31, who longed to eat the crumbs that fell from the table of a rich man.

Loamshire (p. 10)

A fictional English county, created by George Eliot as the setting for Adam Bede (1859), and used by other writers since as a generic name for a rural English setting.

touch him (p. 10)

Ask for a small, informal loan of money (which in practice would often turn out to be a gift).

family sock (p. 10)

An informal (and probably figurative) equivalent for family purse, the cash at hand. The OED cites Wodehouse for the first use of sock in this sense:

Her name was Maudie and he loved her dearly, but the family would have none of it. They dug down into the sock and paid her off.

Uncle George’s barmaid in “Indian Summer of an Uncle” (1930; in Very Good, Jeeves)

racing (p. 11)

Lord Biskerton is among the many Wodehouse characters who lose money betting on horse races.

Bridge (p. 11)

This could have been either Auction Bridge, a card game derived from the Whist family which became popular in England in the 1890s, or its successor Contract Bridge, dating from the mid-1920s and still in current popularity. Wodehouse mentions it from time to time, but rarely to playing it for significant money stakes.

(Those who seek to fleece others at cards in Wodehouse are more usually playing at simple betting games like Persian Monarchs or Blind Hooky, which are easier for a con man to rig; one exception is piquet, at which Hargate cons Spennie, Lord Dreever, in A Gentleman of Leisure/The Intrusion of Jimmy. Bridge is mentioned only in passing in chapter 15 of that novel.)

An incomplete sampling from the early years of Wodehouse’s career:

An Oxford student mentions playing Bridge into the wee hours in “His Subject” (1903). Bridge is recommended for public-school boys in “Our Boys—III” (1903). A painting depicting a gambler is humorously retitled ‘No more Bridge to-night’ in “Academy Notes” (1904). The Smart Set plays bridge in “Our Christmas Pantomime” (1904). An early comic poem about Bridge: “A Bridge Tragedy” (1905). Cheating at bridge is “fashionable” in “What I Think” (1905). Bridge is mentioned in passing in “Between the Innings” (1905). “Playing bridge for stakes a shade too tall” is mentioned in “Wasted Sympathy” (1909). A type of police graft is compared to a double ruff at bridge in The Gem Collector (1909). Psmith’s presence distracts Mr. Bickersdyke at the bridge table in Psmith in the City, ch. 9 (1910; serialized as The New Fold, 1908), and losing money is mentioned. A rather unusual bridge strategy is central to the plot of “The Best Sauce” (1911). One of “The Secret Pleasures of Reginald” (1915) is “not playing bridge with Bodfish, Mrs. Bodfish, and a neighbor.” Auction bridge is recommended as suitable for children’s parties in “Entertaining for the Young” (1915) and as a diversion for winter evenings in “All About the Income-Tax” (1919). Wallace Chesney plays bridge and polo with equal skill in “The Magic Plus Fours” (1922). William Bates would prefer a rubber of bridge to a literary salon in “Jane Gets Off the Fairway” (1924). The possibility of losing money at bridge is mentioned in “High Stakes” (1925). Osbert Mulliner has “some slight skill at contract bridge” in “The Ordeal of Osbert Mulliner” (1928). “Having to learn how to score at contract bridge” is a distraction in “About These Mystery Stories” (1929).

Wodehouse’s daughter Leonora has a humorous take on his style of play in “P. G. Wodehouse at Home” (1929).

“I know your secret!” (p. 11)

This speculative form of blackmail recurs in a later book:

‘I once heard of a fellow who used to go up to prosperous-looking blokes in the street and whisper in their ear “I know your secret”, rightly taking it for granted that every prosperous-looking bloke has one, whereupon the party of the second part, starting guiltily, gave him of his plenty in order to keep his mouth shut. I believe he cleaned up very substantially. But I suppose the finicky would find objections to that. Smacks a little of blackmail.’

Algy Martyn in Company for Henry, ch. 1.3 (1967)

Even when the speaker really does know something about another person, success is not assured:

“Spode,” I said, unmasking my batteries, “I know your secret!”

The Code of the Woosters, ch. 7 (1938); but Bertie forgets the name Eulalie for the time being.

I have always held—rightly, I think—that nothing eases the tension of a difficult situation like a well-spotted bit of blackmail, and it would have been agreeable to have been in a position to go to Stilton and say ‘Cheesewright, I know your secret!’ and watch him wilt.

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 4 (1954)

ashy white (p. 11)

He tottered and his face would, I think, have turned ashy white if his blood pressure hadn’t been the sort that makes it pretty tough going for a face to turn ashy white.

L. P. Runkle in Much Obliged, Jeeves, ch. 16 (1971)

when the fuse blew out (p. 11)

Wodehouse’s writing is hardly ever technical, but this electrical analogy to a sudden failure is such a good one that he used it several times, not always with reference to such a large calamity as finding one’s inheritance to be worthless.

He couldn’t play anything except “The Rosary,” and he couldn’t play much of that. Somewhere around the third bar a fuse would blow out, and he’d have to start all over again.

“Lines and Business” (1912)

“Underhill thought he was marrying a girl with a sizable chunk of the ready, and, when the fuse blew out, he decided it wasn’t good enough.”

Jill the Reckless/The Little Warrior, ch. 8.1 (1920)

“That scheme of yours—reading those books to old Mr. Little and all that—has blown out a fuse.”

“Jeeves in the Springtime” (1921; in ch. 2 of The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

Ever since the luncheon-party had blown out a fuse, her shadow had been hanging over me, so to speak.

“Sir Roderick Comes to Lunch” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

While these little love-affairs of his are actually on, nobody could be more earnest and blighted; but once the fuse has blown out and the girl has handed him his hat and begged him as a favour never to let her see him again, up he bobs as merry and bright as ever.

Bingo Little in The Inimitable Jeeves, ch. 3 (1923)

I was working gaily on it when a fuse blew out in Ziegfeld’s Marilyn Miller show—book by Guy Bolton and Bill McGuire—owing to the lyrist and composer turning up on the day of the start of rehearsals and announcing that they had finished one number, and hoped to have another done shortly, though they couldn’t guarantee this.

Letter to Guy Bolton, November 28, 1927, in Performing Flea (1953)

“The whole bally scheme has blown a fuse.”

“Jeeves and the Song of Songs” (1929; in Very Good, Jeeves, 1930)

It’s a system that answers admirably as a rule, but on the present occasion it blew a fuse owing to the fact that there wasn’t an A.A. scout within miles.

“Jeeves and the Old School Chum” (1930; in Very Good, Jeeves, 1930)

“You are a young fellow in the springtime of life; eager, sanguine, alert for every chance of getting something for nothing. When that chance comes, Corky, examine it well. Walk round it. Pat it with your paws. Sniff at it. And if on inspection it shows the slightest indication of not being all you had thought it, if you spot any possible way which it can blow a fuse and land you eventually waist-high in the soup, leave it alone and run like a hare.”

“Ukridge and the Home from Home” (1931; in Lord Emsworth and Others, 1937)

“Bertie——”

It was, however, only a flash in the pan. She blew a fuse, and silence supervened again.

Madeline Bassett in The Code of the Woosters ch. 10 (1938)

I mean, if Florence was all tied up with him, the peril I had been envisaging could be considered to have blown a fuse and ceased to impend.

Joy in the Morning, ch. 3 (1946)

If their second act seemed to have blown a fuse, she would tell them what to do about it.

Bessie Marbury in Bring On the Girls, ch. 1.3 (1953)

That little gleam of light of which we were speaking a moment ago, the one we showed illuminating Colonel Wyvern’s darkness, went out with a pop, like a stage moon that has blown a fuse.

Ring for Jeeves, ch. 16 (1953)

How he was planning to go on if inspiration hadn’t blown a fuse, I never discovered.

Over Seventy, ch. 18 (1957); also in America, I Like You and Author! Author!)

“Too bad the union blew a fuse, but how sadly often that happens.”

Cocktail Time, ch. 7 (1958)

It seemed to him that the other’s brain, that brain whose subtle scheming had so often chiselled fellow members of the Drones out of half-crowns and even larger sums, must have blown a fuse.

“Leave It to Algy” (in A Few Quick Ones, 1959)

The feeling of bien être to which I just alluded blew a fuse.

“Unpleasantness at Kozy Kot” (in A Few Quick Ones, US edition, 1959)

But as I approached the instrument and unhooked the thing you unhook, I was far from being at my most nonchalant, and when I heard Upjohn are-you-there-ing at the other end my manly spirit definitely blew a fuse.

Jeeves in the Offing, ch. 19 (1960)

“So you gave it the old college try, and it blew a fuse.”

The Plot That Thickened, ch. 12 (1970)

[“and it went wrong” in UK book Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin]

‘I’d like to roll to ’Rio, roll down, roll down to ’Rio…’ (p. 11)

The apostrophes in ’Rio are present only in the Strand magazine and UK editions (except that the Penguin edition of 1953 omits them). Kipling didn’t write them, nor do the US magazine and book include them.

It surprises your annotator to find the verse in Kipling’s Just So Stories for children, following “The Beginning of the Armadillos.”

I’ve never sailed the Amazon,

I’ve never reached Brazil;

But the Don and Magdelana,

They can go there when they will!

Yes, weekly from Southampton,

Great steamers, white and gold,

Go rolling down to Rio

(Roll down—roll down to Rio!)

And I’d like to roll to Rio

Some day before I’m old!

Original US edition at Google Books, including second stanza.

(p. )

(p. )

(p. )

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

(p. )

(p. )

(p. )

(p. )

(p. )

(p. )

(p. )

(p. )

(p. )

Wodehouse’s writings are copyright © Trustees of the Wodehouse Estate in most countries;

material published prior to 1931 is in USA public domain, used here with permission of the Estate.

Our editorial commentary and other added material are copyright

© 2012–2026 www.MadamEulalie.org.