Uncle Dynamite

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

This is part of an ongoing effort by the members of the Blandings Yahoo! Group to document references, allusions, quotations, etc., in the works of P. G. Wodehouse.

Uncle Dynamite has been annotated by Neil Midkiff, with substantial contributions from others as credited below.

Uncle Dynamite has been annotated by Neil Midkiff, with substantial contributions from others as credited below.

Uncle Dynamite was first published on 22 October 1948 by Herbert Jenkins Inc., London, and on 29 November 1948 by Didier, New York. It appeared in one-issue condensations in Liberty (US) and Toronto Star Weekly (CA) after book publication; see this page for details.

These annotations and their page numbers relate to the Didier first US edition, in which the text covers pp. 11–312. For those who are reading other editions, a table of correspondences between the page numbering of several published editions can be seen here (opens in new browser window or tab).

|

Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 |

Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 |

Part One

One

Runs from pp. 3 to 15 in US first edition.

Wockley Junction, Eggmarsh St. John, Ashenden Oakshott, Bishop’s Ickenham (p. 3)

Wodehouse once again shows his skill in making up place names reminiscent of real English towns and sites. Probably the largest one alluded to here is Bishop’s Stortford, a market town in Hertfordshire; other similar real names include Bury St. Edmunds and a hamlet called Oakshott in East Hampshire.

Wodehouse later tells us (p. 45, below) that Ashenden Oakshott is in Hampshire.

sons of the soil (p. 3)

See Very Good, Jeeves.

trouser (p. 3)

As a verb, a typically British colloquialism for putting money (etc.) into one’s pocket, generalized to taking or accepting money; the OED has citations since 1865, and the earliest are from British writers recording or simulating American turns of phrase. Wodehouse is cited in the OED for one use in Laughing Gas (1936).

third-class … first-class (p. 3)

See Something Fresh.

hat was on the side of his head (p. 3)

See The Mating Season.

bore his cigar like a banner (p. 3)

Not a certain reference, but the use of “bore” and “banner” together may be a glancing allusion to Longfellow’s “Excelsior!”; see Sam the Sudden.

usual decent silence of the traveling Englishman (p. 3)

Well-brought-up Britons apparently had a horror of speaking to someone to whom they had not been introduced, especially in trains and other public conveyances. The paragraph on p. 4 beginning “Well, if you hadn’t been—” takes this further.

Lord Ickenham (p. 4)

Introduced in “Uncle Fred Flits By” (1935; in Young Men in Spats, 1936) and Uncle Fred in the Springtime (1939), Frederick Altamont Cornwallis Twistleton is the fifth Earl of Ickenham, uncle of Pongo Twistleton-Twistleton.

five bob (p. 4)

Five shillings, one-fourth of a pound sterling. On the guess that the tip took place during Bill and Pongo’s school days some fifteen years before, roughly 1933, we can estimate an approximate equivalent in current purchasing power [2023] by multiplying by a factor of 60, so this would have the effect of something like £15 or US$20 in round figures today.

half a crown (p. 4)

A coin worth two shillings and sixpence, just half the value of the five bob mentioned above.

something to do with the bone structure of the head (p. 4)

“The fact of the matter is, sir, women haven’t got the heads men have got. I believe it’s something to do with the bone structure.”

Albert Peasemarch in The Luck of the Bodkins, ch. 15 (1935)

“All women are like that,” said George Spenlow. “It’s something to do with the bone structure of their heads. They let their imagination run away with them. They entertain unworthy suspicions.”

“Birth of a Salesman” (1950; in Nothing Serious, 1950)

“All women are like that,” said Bill. “It’s something to do with the bone structure of our heads.”

Wilhelmina “Bill” Shannon in The Old Reliable, ch. 16 (1951)

The Duke, a clear-headed man, saw the objection to this immediately, and once again the inability of females to reason anything out impressed itself upon him. It was something, he believed, to do with the bone structure of their heads.

The Duke of Dunstable in A Pelican at Blandings, ch. 4.1 (1969)

she went of her own free will (p. 4)

Lord Ickenham pretends to have misunderstood “Jamaica?” as a slurred form of “Did you make her?” for the sake of wordplay.

Peter Stanford noted in the Facebook P. G. Wodehouse Book Club that even at the time of writing, this was “a hoary old Music Hall joke”; it was not original with Uncle Fred or with Wodehouse.

human tomato (p. 5)

Wodehouse compared a pink or red complexion to a tomato a few other times:

He started to get pink in the ears, and then in the nose, and then in the cheeks, till in about a quarter of a minute he looked pretty much like an explosion in a tomato cannery on a sunset evening.

Cyril Bassington-Bassington in “Jeeves and the Chump Cyril” (1918; in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

There entered a small boy in an Eton suit, whose face seemed to the bishop vaguely familiar. It was a face that closely resembled a ripe tomato with a nose stuck on it…

“The Bishop’s Move” (1927; in Meet Mr. Mulliner, 1927/28)

“Ronald! Goes about behaving like a bereaved tomato.”

Galahad Threepwood referring to Ronnie Fish’s pinkness in Summer Lightning, ch. 8 (1929)

Aunt Dahlia’s face grew darker. Hunting, if indulged in regularly over a period of years, is a pastime that seldom fails to lend a fairly deepish tinge to the patient’s complexion, and her best friends could not have denied that even at normal times the relative’s map tended a little toward the crushed strawberry. But never had I seen it take on so pronounced a richness as now. She looked like a tomato struggling for self-expression.

Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 20 (1934)

His eyes were rolling in their sockets, and his face had taken on the color and expression of a devout tomato. I could see that he loved like a thousand of bricks.

Stilton Cheesewright blushing when acknowledging his engagement in Joy in the Morning, ch. 3 (1946)

Inasmuch as Captain Biggar, as we have seen, had not spoken his love but had let concealment like a worm i’ the bud feed on his tomato-coloured cheek, it may seem strange that Mrs. Spottsworth should have known anything about the way he felt.

Ring for Jeeves/The Return of Jeeves, ch. 6 (1953/54)

Kirk Rockaway hesitated for a moment. He seemed to be blushing, though it was hard to say for certain, his face from the start having been tomatoesque.

“Stylish Stouts” (1965; in Plum Pie, 1966/67)

bestrides the world like a Colossus (p. 5)

A slight paraphrase from Julius Caesar: see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

Moab is his washpot and over what’s-its-name has he cast his shoe (p. 5)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

face his tailor without a tremor (p. 5)

Apparently Pongo, like many of Wodehouse’s young men, has been dilatory about paying for his clothes.

unexpectedly wide vocabulary (p. 5)

That is, responding “Good” instead of “Fine.”

protégé (p. 5)

The UK edition has the feminine form protégée here, more correct when the person who is being sponsored, guided, or protected is female.

sense enough for two (p. 5)

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

something with a platinum head and an Oxford accent (p. 6)

The implication is that Pongo is likely to be ensnared by dyed pale-blonde hair and an acquired accent that implies more education or social standing than the young woman possesses.

flitting from flower to flower like a willowy butterfly (p. 6)

Little Lord Fauntleroy suits (p. 6)

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime, and be sure to follow the link to the illustration in the original book.

Can the leopard change his spots, or the Ethiopian his hue? (p. 6)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

sunburned (p. 6)

Wodehouse seems sometimes to use this to mean a deep brown tan acquired over time in the sun, as well as its more common modern use for the bright pink or red of an acute reaction to overexposure to the sun, as in sorer than a sunburned neck: see The Girl on the Boat. See also Meet Mr. Mulliner regarding the social history of tanning.

When I got back to Ebury Street, Bowles, my landlord, after complimenting me in a stately way on my sunburned appearance, informed me that George Tupper had called several times while I was away.

“No Wedding Bells for Him” (1923; in Ukridge, 1924)

Miss Angela Purdue … was one of these jolly, outdoor girls; and Wilfred had told me that what attracted him first about her was her wholesome, sunburned complexion. … “It’s such a pity,” said Miss Purdue, “that the sunburn fades so soon. I do wish I knew some way of keeping it.”

“A Slice of Life” (1926; in Meet Mr. Mulliner, 1927/28)

“How brown you are!”

“That’s Montego Bay. I worked on this sunburn for three months.”

Jill Wyvern to Monica Carmoyle in Ring for Jeeves, ch. 3/The Return of Jeeves, ch. 2 (1953/54)

Ashenden really belongs to me (p. 6)

Bill is in much the same situation as Spennie, Lord Dreever, at Dreever Castle:

The castle was now a very comfortable country-house, nominally ruled over by Hildebrand Spencer Poyns de Burgh John Hannasyde Coombe-Crombie, twelfth Earl of Dreever (“Spennie” to his relatives and intimates), but in reality the possession of his uncle and aunt, Sir Thomas and Lady Julia Blunt.

A Gentleman of Leisure, ch. 8 (1910)

bally (p. 6)

Rhymes with “tally”; a very slangy intensive adjective, usually used as an euphemism for bloody; it has the effect of a mild imprecation such as “confounded” or “blasted.”

a shoe like a violin case (p. 7)

See Laughing Gas.

moot (p. 8)

See Money for Nothing.

girding up your loins (p. 8)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

to rouse the emotions and purge the soul with pity and terror (p. 8)

See The Girl on the Boat.

penny-in-the-slot machine (p. 9)

See Thank You, Jeeves.

Silver Band (p. 9)

See Hot Water.

looking like a stag at bay (p. 10)

Alluding to the popular painting by Sir Edwin Landseer; see Right Ho, Jeeves.

a whoop and a holler (p. 10)

See Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit.

wolves … sleigh … Russian peasant (p. 10)

See Full Moon.

the chap in Damon Runyon’s story (p. 11)

Norman Murphy (A Wodehouse Handbook) found this in Runyon’s “A Nice Price” (1934); the chap is Sam the Gonoph. See the quotation in context, the second paragraph of p. 262, at the Internet Archive (login required to “borrow” the book).

spreading sweetness and light (p. 11)

See Sam the Sudden.

a first-class earl who keeps his carriage (p. 11)

Quoting Gilbert & Sullivan’s Patience, from Archibald Grosvenor’s poem about Gentle Jane. See the libretto at gsarchive.net.

durbar (p. 11)

See Carry On, Jeeves.

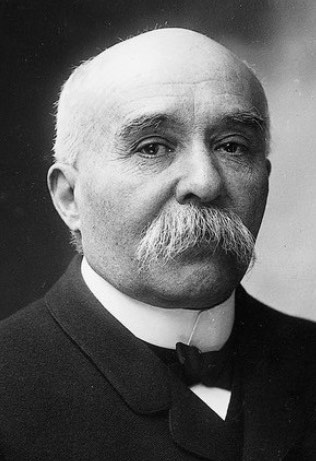

Clemenceau (p. 11)

Clemenceau (p. 11)

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (1841–1929); Prime Minister of France 1906–09 and 1917–20.

connected with the Brazil nut industry (p. 12)

Lord Ickenham would later himself be closely connected with a Brazil nut, the one he uses in Cocktail Time, ch. 1 (1958), to knock off the top hat of Sir Raymond Bastable. In Service With a Smile, chs. 2 and 3 (1961), he brings Cuthbert “Bill” Bailey to Blandings Castle under the alias of Meriwether, pretending that he is connected with the Brazil nut industry.

go to the Rocky Mountains and shoot grizzlies (p. 12)

See A Damsel in Distress.

I could have stuck on a lot of dog (p. 12)

See Spring Fever.

the sort of man whose bite spells death (p. 13)

“Is your sister Adela what is technically known as a tough baby?”

“None tougher. Her bite spells death.”

Spring Fever, ch. 9 (1948)

all-in wrestler (p. 13)

All-in is a type of wrestling without restrictions, with virtually every type of hold permitted. [JD]

kills rats with his teeth (p. 13)

Bertie Wooster claims that his Aunt Agatha chews broken bottles and kills rats with her teeth (The Mating Season, ch. 1, 1949).

governor of one of those crown colonies (p. 13)

Colonial governors and their widows appear in a few other stories:

As a Colonial governor [Sir Godfrey Tanner, K.C.M.G.] had just that taste of power and authority which is enough for the sensible man; more might have spoiled him for the simpler pleasures of life; less would have left him restless and unsatisfied.

“Creatures of Impulse” (1914)

The late Sir Rupert Lakenheath, K.C.M.G., C.B., M.V.O., was one of those men at whom their countries point with pride. Until his retirement on a pension in the year 1906, he had been Governor of various insanitary outposts of the British Empire situated around the equator, and as such had won respect and esteem from all.

“Ukridge Rounds a Nasty Corner” (1924; in Ukridge)

This father of Aurelia’s was not one of those mild old men who make nice easy insulting. He was a tough, hard-bitten retired Colonial Governor of the type which comes back to England to spend the evening of its days barking at club waiters.

“The Code of the Mulliners” (1935; in Young Men in Spats, 1936)

It is only very rarely that there can exist a perfect fusion of soul between the widow of a British colonial governor, accustomed to associate with service people in a town like Cheltenham, and a girl who is not only American (always a suspicious thing to be) but who lives in Paris (of all cities the one with the most dubious reputation) and is probably a bohemian with loose friends who drink absinthe and play guitars in studios.

Frozen Assets/Biffen’s Millions, ch. 7 (1964)

Mugsy (p. 13)

The only other Mugsy in Wodehouse is Howard “Mugsy” Steptoe in Quick Service (1940), an ex-boxer with a squashed nose. The nickname may possibly derive from the slang sense of mug to mean an unattractive face; see Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

six of the juiciest with a fives bat (p. 13)

See Sam the Sudden and The Pothunters.

taking her on to Crewe (p. 14)

Alluding to the music-hall song “Oh! Mr. Porter” (1892) made famous by Marie Lloyd. Wikipedia article. Lyrics, with link to sheet music.

come Lammas Eve (p. 14)

July 31, the evening before Lammas, a religious celebration of the first fruits of the harvest. The name comes from the Anglo-Saxon for Loaf-Mass, a ceremony in which bread made from the first yield of grain is eaten.

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for the source in Romeo and Juliet and other references in Wodehouse to the phrase.

Gawd-help-us (p. 14)

cut by the county (p. 14)

See two adjacent notes to Laughing Gas.

behind the ear with a sock full of wet sand (p. 15)

Another way of describing a knockout blow to the base of the skull with a sandbag.

…he’ll drop as if you had hit him behind the ear with a sandbag.

“The Love-r-ly Silver Cup” (1915)

any interruption at such a moment would have affected him like a blow behind the ear from a sandbag…

Bill the Conqueror, ch. 16.2 of serial; ch. 14.2 of book (1924)

At this point, when everything was going as sweet as a nut and I was feeling on top of my form, Mrs. Pringle suddenly soaked me on the base of the skull with a sandbag.

“Without the Option” (1925; in Carry On, Jeeves!, 1925/27)

Blair Eggleston was looking as like a younger English novelist who has just stopped a sandbag with the back of his head as any younger English novelist had ever looked…

Hot Water, ch. 2.5 (1932)

The future Onion Soup King was exhibiting all the symptoms of one who has been struck on the back of the head with a sock full of wet sand.

Uncle Fred in the Springtime, ch. 17 (1939)

He hopped nimbly on to the platform, prattling gaily, quite unaware that he had to all intents and purposes just struck an estimable young man behind the ear with a sock full of wet sand.

Uncle Dynamite, ch. 1 (1948)

The information which she had sprung on me had, I need scarcely say, affected me like the impact behind the ear of a stocking full of wet sand.

The Mating Season, ch. 10 (1949)

It took Aunt Dahlia right between the eyes like a sock full of wet sand.

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 19 (1954)

It is as if the Mirror had crept up behind America and struck her on the back of the head with a sock full of wet sand.

“Grave News from America” (in Punch, August 18, 1954)

Also as “Say It with Rattlesnakes” in America, I Like You (1956)

and “Christmas and Divorce” in Over Seventy (1957)

He had the momentary illusion that the management of Barribault’s, however foreign to their normal policy such an action would have been, had hit him over the head with a sock full of wet sand.

Something Fishy/The Butler Did It, ch. 9 (1957)

His eyes were round, his nose wiggled, and one could readily discern that this news item had come to him not as rare and refreshing fruit but more like a buffet on the base of the skull with a sock full of wet sand.

Jeeves in the Offing, ch. 7 (1960)

gulping grunt, like that of a bulldog … while eating a mutton chop (p. 15)

Biffy made a sort of curious gulping noise not unlike a bulldog trying to swallow half a cutlet in a hurry so as to be ready for the other half.

“The Rummy Affair of Old Biffy” (1924; in Carry On, Jeeves!, 1925)

[Orlo Porter’s] voice was low and guttural, like that of a bull-dog which has attempted to swallow a chump chop and only got it down half-way.

Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen, ch. 2 (1974)

Two

Runs from pp. 16 to 29 in US first edition.

Buffy-Porson (p. 16)

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

two-seater (p. 16)

A small, lightweight car with room for only the driver and one passenger. Typically a sporty car with a convertible top, bought by people who enjoy driving themselves rather than being driven by a chauffeur.

restoring his tissues (p. 16)

See Bill the Conqueror.

Goodwood Cup (p. 17)

Horse races have been held on the Duke of Richmond’s estate on the Sussex Downs since 1802. The Goodwood Cup takes place at the beginning of August, and is one of the classic summer events for the fashionable world. (cf. “Bingo Has a Bad Goodwood”, ch. 12 of The Inimitable Jeeves, originally part of the magazine story “Comrade Bingo” from 1922)

what you would do … if you found a dead body in your bath one morning with nothing on but a pair of spats (p. 17)

Probably a take-off on Whose Body? by Dorothy L. Sayers (1923), in which Lord Peter Wimsey is introduced, detecting a case of a dead body found in a bath wearing nothing but a pair of pince-nez spectacles.

‘Peace, perfect peace, with loved ones far away’ (p. 17)

See Biblia Wodehousiana. The hymn, however, poses this line as a question, asking how one’s mind can be at rest when friends and family are not safe at home, and answering it with the assurance of divine protection. Wodehouse typically quotes it, as here, with a humorous alteration to its meaning: that it is more peaceful without the loved ones nearby.

Eustace became aware, as never before, of the truth of that well-known line—“Peace, perfect peace, with loved ones far away.” There was certainly little hope of peace with loved ones in his bedroom.

The Girl on the Boat, ch. 17.3 (1922)

He looked forward contentedly to a succession of sunshine days of peace, perfect peace with loved ones far away; days when he would be able to work in his garden without the fear, which had been haunting him for the last two weeks, of finding his niece drooping wanly at his side and asking him if he was wise to stand about in the hot sun.

“Company for Gertrude” (1928; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

How right, he felt, the author of the well-known hymn had been in saying that peace, perfect peace, is to be attained only when loved ones are far away.

Service With a Smile, ch. 2.3 (1961)

“This is very pleasant, Galahad,” he said, and Gally endorsed the sentiment.

“I was thinking the same thing, Clarence. No Connie, no Dunstable. Peace, perfect peace with loved ones far away, as one might say.”

A Pelican at Blandings, ch. 14 (1969)

I had looked on Maiden Eggesford as somewhere where I would be free from all human society, a haven where I would have peace perfect peace with loved ones far away, as the hymnbook says, and it was turning out to be a sort of meeting place of the nations.

Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen, ch. 6 (1974)

Coggs (p. 17)

Lord Ickenham’s butler is first mentioned in Uncle Fred in the Springtime (1939). Coggs is a variant of Wodehouse’s favorite butler name, Keggs. [MH]

St. Anthony … temptation (p. 17)

See Bill the Conqueror.

one of our pleasant and instructive afternoons (p. 18)

So when, on the occasion to which I allude, he stood pink and genial on Pongo’s hearth-rug, bulging with Pongo’s lunch and wreathed in the smoke of one of Pongo’s cigars, and said: “And now, my boy, for a pleasant and instructive afternoon,” you will readily understand why the unfortunate young clam gazed at him as he would have gazed at two-penn’orth of dynamite, had he discovered it lighting up in his presence.

“Uncle Fred Flits By” (1935; in Young Men in Spats, 1936)

“No, sorry, three pangs. What caused one of them was the thought that, going off to stay with Johnny, I shall be deprived for quite a time of your society and those pleasant and instructive afternoons we have so often had together.”

Cocktail Time, ch. 7 (1958)

“I know,” said Pongo austerely. “One of our pleasant and instructive afternoons. Well, pleasant and instructive afternoons are off.”

Service With a Smile, ch. 2 (1961)

a thoughtful Crumpet had once said (p. 18)

The Crumpet (a member of the Drones Club; see Uncle Fred in the Springtime) uses very similar language to describe Uncle Fred and his “excesses” in “Uncle Fred Flits By” (1935; in Young Men in Spats, 1936) and the later novels in which he appears; see Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

step high, wide and plentiful (p. 19)

See Young Men in Spats.

well stricken in years (p. 19)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Later, in ch. 6.2, Lord Ickenham’s age is established at sixty.

that day at the dog races (p. 19)

We never get the full story of what happened, but hints about the circumstances of being arrested are revealed later in this book, and the incident is mentioned at least obliquely in all the Uncle Fred stories.

losing dear gazelles (p. 19)

See Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit.

cloud … some sort of a silver lining (p. 19)

See Bill the Conqueror.

West End (p. 20)

See Bill the Conqueror.

up and doing with a heart for any fate (p. 20)

From the last stanza of an often-quoted Longfellow poem; see Leave It to Psmith.

with my hair in a braid (p. 20)

See The Mating Season.

Recording Angel (p. 20)

A personification of the heavenly record-keeping of one’s good and bad deeds. Wodehouse twice uses the term to refer to the angel in James Leigh Hunt’s poem “Abou Ben Adhem.”

Get thou behind me (p. 20)

Pongo isn’t quite tuned in to Elizabethan grammar here; the Authorized (King James) Version has “Get thee behind me.” See Biblia Wodehousiana.

get into an uncle’s ribs (p. 21)

along the primrose path (p. 21)

Alluding to Ophelia’s caution to Laertes in Hamlet; see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

It’s no good saying ‘Ichabod’ (p. 21)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.sponge-bag trousers (p. 21)

Part of formal morning attire, appropriate for weddings; see The Code of the Woosters.

neither chick nor child (p. 22)

An archaic phrase for having no offspring; unlike the usage of twentieth-century slang, a chick referred to a boy and a child meant a girl, according to NTPM in A Wodehouse Handbook.

take a dekko (p. 22)

Take a look; British army slang from the 1890s, derived from Hindi dekho, imperative form of the verb “Look!”

photograph … of cabinet size (p. 22)

See Leave It to Psmith.

winter woolies (p. 23)

Long underwear made of wool.

lily-livered poltroon (p. 24)

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

district messenger boy (p. 24)

See Leave It to Psmith.

put the lid on it (p. 25)

See Ukridge.

like a sheik (p. 25)

In a domineering manner, like the romantically captivating hero of Edith Maude Hull’s 1919 novel The Sheik, famously portrayed in a 1921 silent film by Rudolph Valentino. [MH/NM]

Take some jewelry … and smuggle it through the customs (p. 26)

Plum and Ethel Wodehouse had had an experience that may have informed this plot device:

On arriving in New York, we had a passing unpleasantness with the Customs people. Ethel had bought a necklace in London, and she filled up the form they give you to fill up before you land with “Nothing to Declare,” and the Customs people decided that here was the jewel smuggler they had been waiting for so long.

Letter to Bill Townend dated December 16, 1922 in Author! Author! (1962)

“Grayce has bought a peach of a pearl necklace in Paris, and she wants you, when you sail for home next week, to take it along and smuggle it through the Customs.”

Mabel Spence to Ivor Llewellyn in The Luck of the Bodkins, ch. 1.2 (1935). Note that when the story is recounted by a Whiskey Sour in Chapter 2 of Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin (1972), the jewelry is called “a very valuable diamond thingummy” rather than a pearl necklace.

“Do you remember when she smuggled her pearls through the New York Customs?”

“Inside a Mickey Mouse which she bought at the ship’s shop.”

Mr. Bunting and Mr. Satterthwaite, talking about Julia Cheever in “Life with Freddie” (in Plum Pie, 1966/67)

sheet anchor (p. 27)

From the former name for the largest of a ship’s anchors, to be used only in an emergency; figuratively, something upon which one relies in extreme circumstances.

commish (p. 27)

A shortening of “commission” as in the 1920s craze for shortened words, such as the Gershwin song “ ’S Wonderful” (1927), whose verse rhymes humble fash and tender pash.

whitest man I know (p. 27)

See A Damsel in Distress.

reminded me of Hamlet (p. 28)

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for other references to Hamlet’s character.

apple-pie bed (p. 28)

See Summer Lightning.

a couple for the tonsils (p. 28)

angel in human shape (p. 28)

See Full Moon.

about fifty-seven romances (p. 29)

See A Damsel in Distress.

George Eliot (p. 29)

Pen name of English author Mary Ann Evans (1819–1880).

Boadicea (p. 29)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

the late Mrs. Carrie Nation (p. 29)

American reformer (1846–1911) known for radical advocacy of the temperance movement; notorious for smashing up taverns and bottles of alcoholic beverages with a hatchet.

twenty-minute egg (p. 29)

See Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit.

“Shall we join the ladies?” (p. 29)

At the time, according to British etiquette for a formal dinner, after the last course was finished, the hostess and female guests retired to the drawing room, allowing the host and his male guests to turn the conversation to more masculine topics, and to enjoy an after-dinner drink, typically port. This phrase would have been the conventional signal for the men to conclude their separate session and go to the drawing room themselves.

Three

Runs from pp. 30 to 58 in US first edition.

tra-la-la (p. 30)

A conventional phrase representing the singing of a wordless melody or sequence of notes, often expressing joy or freedom from care.

Summer is here. (If I had been writing a lyric for musical comedy I should have added the words Tra-la-la, tra-la-la, but in a serious and technical article these would, of course, be out of place.)

“A Timely Chat About Gardens” (1916)

“Tra-la-la!” I said.

“Precisely, sir.”

“Aunt Agatha Takes the Count” (1922; in ch. 3 of The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

“Gentleman, eh?” said Mr. Slingsby, almost adding “Tra-la-la!”

Bill the Conqueror, ch. 18 (1924)

It was, indeed, practically with a merry tra-la-la on my lips that I latchkeyed my way in and made for the sitting room.

The Code of the Woosters, ch. 1 (1938)

I marmaladed a slice of toast with something of a flourish, and I don’t suppose I have ever come much closer to saying “Tra-la-la” as I did the lathering, for I was feeling in mid-season form this morning.

Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 1 (1963)

successfully resisted a Tempter (p. 30)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

tied the can (p. 30)

See Sam the Sudden.

“Faugh!” (p. 30)

See Very Good, Jeeves.

crust (p. 30)

See the discussion under immortal rind in Something Fresh.

old geezers (p. 31)

avuncular (p. 31)

Used here in its root sense of “of or from an uncle” without its usual connotation of being benign or kindly. Wodehouse uses it both ways:

Two weeks of poker had led to his writing to his uncle a distressed, but confident, request for more funds; and the avuncular foot had come down with a joyous bang.

The Intrusion of Jimmy/A Gentleman of Leisure, ch. 23 (1910)

The light of avuncular affection died out of the old boy’s eyes.

Bertie, breaking the news of Bingo’s engagement to a waitress to Bingo’s uncle Mortimer Little in “Bingo and the Little Woman” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923))

from soup to nuts (p. 31)

See Blandings Castle and Elsewhere.

Cheeryble Brother (p. 31)

See Hot Water.

grappling them to his soul with hoops of steel (p. 31)

Alluding to Polonius’s speech of advice in Hamlet; see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

Ashenden Manor … a fortress to be defended against uncouth intruders (p. 31)

Compare the description of Dreever Castle as a haven of refuge from marauding invaders in The Intrusion of Jimmy/A Gentleman of Leisure, ch. 8 (1910).

French window (p. 32)

See Summer Lightning.

a different and a dreadful world (p. 32)

See Very Good, Jeeves.

whatnot (p. 32)

Here, an indefinite or undescribable object. See A Damsel in Distress for other meanings and uses of the term.

trade gin (p. 32)

Gin (a distilled spirit flavored with juniper berries) bottled for the purpose of bartering with indigenous peoples. No doubt this was not the highest quality liquor.

knobkerrie (p. 32)

(Afrikaans) A short weighted club or throwing stick. [MH]

Last Trump (p. 32)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

macédoine (p. 32)

See Ice in the Bedroom.

foot on the self-starter (p. 33)

See Bill the Conqueror.

a trapped cinnamon bear (p. 33)

See A Damsel in Distress.

looked like a horse (p. 34)

See Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit.

brightness enough for both of them (p. 34)

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

pot of cyanide (p. 34)

See Thank You, Jeeves.

the status of an ewe lamb (p. 35)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Lower Barnatoland (p. 35)

A fictional British colony in Africa, whose name is derived from the real Lower Basutoland and from British diamond magnate Barney Barnato (1852–97). A. M. “Pitcher” Binstead of the Pelican Club had used the name “Barnatoland” by itself in “The Gents of the Garrison” (in Houndsditch Day by Day, 1899).

In Frozen Assets/Biffen’s Millions, ch. 7 (1964), Wodehouse tells us that the late Sir Hubert Blake-Somerset, Henry’s father, had been governor of Lower Barnatoland.

brilliantined hair (p. 35)

See Leave It to Psmith.

look for the silver lining and try to find the sunny side of life (p. 35)

Quoting the lyrics of a song; see Bill the Conqueror.

stewed to the gills (p. 36)

Very drunk; see Right Ho, Jeeves.

One fairly quick, followed by another rather slower (p. 36)

clicking noise, like a wet finger touching hot iron (p. 37)

Somewhat inconsistent with another mention:

Occasionally he would draw in his breath with a sharp hissing sound like somebody putting a wet finger on a hot stove lid…

“My Bridge Career” (in Cavalier, March 1965)

young toad (p. 37)

The Hon. Galahad listened with fire smouldering behind his monocle.

“The young toad!” he cried. “Monty Bodkin.”

Heavy Weather, ch. 9 (1933)

“Half-witted, I’d call him—if that. Besides being the most offensive-looking young toad I’ve ever seen on the premises.”

Sir Mortimer Prenderby, speaking of Freddie Widgeon in “Good-Bye to All Cats” (1934; in Young Men in Spats, 1936)

Jane, the parlormaid (p. 38)

In many households, servants were addressed by names not their own; the parlormaid might be called Jane, no matter what she had been christened, as if she were taking on a role in a play.

deleterious slab of damnation (p. 38)

The phrase “slab of damnation” appears to be original with Wodehouse; Google Books search finds no instance prior to the first of these:

“Well, he looks a pretty frightful young slab of damnation to me.”

Sir Mortimer Prenderby, speaking of Freddie Widgeon in “Good-Bye to All Cats” (1934; in Young Men in Spats, 1936)

“That slimy, slithery, moustache-twiddling young slab of damnation?”

Lord Uffenham speaking of Lionel Green in Money in the Bank, ch. 7 (1942)

“Who invited Cheesewright here? Dahlia, I suppose, though why we shall never know. A deleterious young slab of damnation, if ever I saw one.”

Uncle Tom Travers in Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 11 (1954)

“When the wench … sprang it on me as calm as a halibut on ice that she was going to marry Stanhope Twine, I nearly swooned where I sat. ‘What!’ I said. ‘That young slab of damnation? Yer kiddin.’ ”

Lord Uffenham in Something Fishy/The Butler Did It, ch. 13 (1957)

“There was a young slab of damnation with a criminal face round at my place only yesterday trying to sell it to me.”

Major Plank in Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 23 (1963)

“You mean you seriously intend to marry that pop-eyed young slab of damnation?”

Colonel Pashley-Drake speaking of Lancelot Bingley in “A Good Cigar Is a Smoke” (in Plum Pie, 1966/67)

coo to him like a turtledove (p. 38)

Practically a coo. As it might have been one turtledove addressing another turtledove.

Joy in the Morning, ch. 2 (1946)

“I’ll be like a turtledove cooing to a female turtledove.”

Ring for Jeeves/The Return of Jeeves, ch. 6 (1953/54)

Stiffy … had spoken of Stinker cooing to Spode like a turtledove, and if memory served me aright that was just how he had cooed, and it was of a cooing turtledove that she now reminded me.

Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 19 (1963)

see each other steadily and see each other whole (p. 39)

A paraphrase from a Matthew Arnold poem: see The Clicking of Cuthbert.

top dressing of mustache (p. 39)

Top dressing is an agricultural term for mulch, compost, or fertilizer spread on the surface of garden soil. Wodehouse often uses it for such things as books and papers spread over a desk; this is the only instance so far found applying it to facial hair as itself being spread upon a face, though once it is used for Chimp Twist waxing his mustache (Money in the Bank, ch. 5, 1942), and once Bertie contemplates fertilizing his mustache in these terms:

I had hoped to nurse it through the years with top dressing till it became the talk of the town.

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 22 (1954)

gumboil (p. 39)

An infected sore or inflammation on the gums in the mouth; figuratively, an annoying or irritating person.

clocked socks (p. 39)

Socks with decorative embroidery at the ankles.

“It’s priceless.”

“Really? How priceless!” (p. 40)

Sir Aylmer uses the word in its usual sense of having an inestimable value; Pongo’s response is in the colloquial sense of being original, amusing, or absurd, as Bertie and his pals often use it:

It wasn’t as if there was anything wrong with that Broadway Special hat. It was a remarkably priceless effort, and much admired by the lads.

“Jeeves and the Unbidden Guest” (1916; in Carry On, Jeeves, 1925)

like breath off a razor blade (p. 40)

Apparently also an original Wodehouse simile; a Google Books search finds no earlier usage.

There was a light breeze blowing in through the open window, and so musical a rustling did it set up as it played about the heaped-up wealth that Mr. Nickerson’s austerity seemed to vanish like breath off a razor-blade.

“Ukridge’s Dog College” (1923; in Ukridge, 1924)

And then his eye fell on the slip of paper, and pomposity slipped from him like breath off a razor blade.

Money for Nothing, ch. 14.2 (1928)

Lord Emsworth had been smirking. He now congealed, and the smile passed from his lips like breath off a razor blade, to be succeeded by a tense look of anxiety and alarm.

“The Crime Wave at Blandings” (1936; in Lord Emsworth and Others, 1937)

The puzzled frown that had begun to gather on Lord Emsworth’s forehead vanished like breath off a razor blade.

A Pelican at Blandings, ch. 1.1 (1969)

“Gorbl . . .!” (p. 40)

Gorblimey: a Cockney contraction of “God blind me” to express surprise, anger, etc. [IM/LVG]

Sir Aylmer was one of them (p. 40)

See Hot Water.

like Marius among the ruins of Carthage (p. 41)

See Something Fresh.

whirring sound without (p. 41)

For this sense of “without” see confused noise without in Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

some solid body was passing down the hall at a high rate of m.p.h. (p. 41)

See The Girl on the Boat.

measles (p. 41)

Measles was a highly infectious virus for which no vaccine was available until 1963.

bravest and fairest (p. 42)

Belshazzar’s Feast (p. 42)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

to judge the babies (p. 42)

See Bill the Conqueror for other Wodehouse references to baby-judging contests.

lumbago (p. 42)

Pain in the muscles of the lower back.

dashed (p. 43)

See A Damsel in Distress.

eye, rolling in a fine frenzy from heaven to earth (p. 43)

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

soul in torment (p. 43)

See Sam the Sudden.

blinding and stiffing (p. 44)

See The Mating Season.

went on toots (p. 45)

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

the pure Hampshire breezes (p. 45)

the pure Hampshire breezes (p. 45)

Hampshire is a ceremonial county on England’s southern coast, containing the cities of Southampton and Portsmouth.

awful majesty of the law (p. 46)

See Ice in the Bedroom.

Potter, the Romeo (p. 46)

For similar references, see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

a fair cop (p. 46)

An arrest when the perpetrator has been caught dead-to-rights, in the act. [JD]

Boat Race Night (p. 47)

See Laughing Gas and The Code of the Woosters.

“What’s all this?” (p. 47)

Policemen in Wodehouse always say “What’s all this?” and “Ho!” This is a running joke throughout the canon, presumably sending up the way the walk-on policemen in plays of the time talk. [MH]

enclosed premises (p. 47)

Under the Vagrancy Act 1824, “being found on enclosed premises” was grounds for arrest on suspicion of being there for unlawful purposes. The text of the law actually read “being found in or upon any Dwelling House, Warehouse, Coach-house, Stable, or Outhouse, or in any inclosed Yard, Garden, or Area,” but the shorter phrase was the usual abbreviated reference.

tête-à-tête (p. 47)

A face-to-face meeting (from French: “head to head”).

turned-up nose (p. 47)

According to the OED, this means the same as Wodehouse’s more usual adjective tip-tilted: see A Damsel in Distress.

chewing the fat (p. 48)

To discuss or complain about something, especially at length. One of the OED citations for this phrase is from Money in the Bank, ch. 12 (1942).

mooch along (p. 49)

To move, especially in an aimless or uncertain fashion.

I was mooching slowly up St. James’s Street…

“Comrade Bingo” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

“R.” (p. 50)

Wodehouse doesn’t otherwise seem to characterize Elsie’s dialectal pronunciations, but spelling “Ah” as “R” gives a hint as to her manner of speech.

Others thus characterized include the woman in the cricket cap in Summer Moonshine, ch. 19 (1937); Augustus Robb in Spring Fever, ch. 8 (1948); Constable Ernest Dobbs in The Mating Season, ch. 26 (1949); George Cyril Wellbeloved in Pigs Have Wings, ch. 5.6 (1952); and an employee of Pop Cook in Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen, ch. 17 (1974). This does not purport to be a complete list.

Bottleton East (p. 50)

See Young Men in Spats.

spliced to a copper (p. 50)

Married to a policeman. Spliced as slang for married is cited as early as 1751, from Smollett; copper for policeman has OED citations since 1846.

a blot on the Bean escutcheon (p. 51)

See Heavy Weather. Using terms of heraldry for Elsie’s Bottleton East family is a humorous misapplication.

resigned his portfolio (p. 51)

See Lord Emsworth and Others. A term from high diplomatic and government circles, also humorously misapplied.

three hundred pounds (p. 51)

The Bank of England inflation calculator suggests a factor of roughly thirty to account for purchasing-power change from 1948 to 2023, so in modern terms this would be on the order of nine thousand pounds. I doubt if any pubs can be bought for that sum today, of course.

overbearing dishpot (p. 52)

Wodehouse never explains Elsie’s term; presumably we are to conclude that she really means “despot.”

good egg (p. 52)

The term is usually applied to a person of reliable character in Wodehouse, but here it seems to refer to the scheme of getting married to Hermione.

The Boy Explorers Up The Amazon (p. 53)

Apparently fictitious.

liver wing (p. 53)

The right wing of a chicken or other fowl, with the liver tucked into it before cooking. OED has quotations dating from 1796.

kick the bucket (p. 53)

See Thank You, Jeeves.

‘Coo!’ (p. 53)

An exclamation of surprise or amazement; often a verbal marker for those of humbler origins. When Elsie later in this chapter (p. 58) quotes Pongo as saying “Coo! I think I’ll go to London” we are intended, I think, to regard the exclamation as Elsie’s own interpolation rather than a direct quote from Pongo.

His Nibs (p. 53)

See A Damsel in Distress.

one of those peculiar puddings (p. 54)

Pudding is here used in the British sense of any dessert; the description is of “baked Alaska”: a block of ice cream on a base of cake, the whole covered in meringue and briefly oven-baked to crisp and brown the surface of the meringue, while the ice cream insulated inside stays frozen.

nice bit of box fruit (p. 55)

See Laughing Gas.

a dozen miles … in about three minutes and a quarter (p. 55)

Taken literally, this works out to just over 221.5 miles per hour.

understudy (p. 55)

Theatrical jargon for an actor who prepares to play a role in the absence or illness of the actor who normally portrays that part.

the fate that is worse than death (p. 56)

See Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit.

goggle-eyed (p. 56)

See Piccadilly Jim.

lip fungus (p. 56)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

in the soup (p. 56)

going down for the third time (p. 56)

kissing her in a grateful and brotherly manner (p. 56)

Consequently James stooped, and—in a purely brotherly way—kissed Violet.

“Out of School” (1910)

everybody kisses everybody else … like the early Christians (p. 57)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Can the leopard change his spots (p. 57)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

non compos (p. 58)

See Cocktail Time.

Four

Runs from pp. 59 to 73 in US first edition.

Budge Street (p. 59)

Apparently fictitious; the 1915 London directory lists a Budge Row in the City of London (E.C.), and Google Maps shows a Budge Lane in Mitcham, but these are nowhere near Chelsea.

the Enclosure at Ascot on Cup Day (p. 59)

In full, the Royal Enclosure at the Ascot Racecourse, the most formal members-only-by-invitation section of the most prestigious racing venue in the United Kingdom, founded in 1711 by Queen Anne. Formal morning dress is mandatory for gentlemen.

King’s Road (p. 60)

When Wodehouse moved to London in 1900 to begin working at the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, he first rented rooms in Markham Square, Chelsea, then in Walpole Street. Both were just off the King’s Road, so he knew the neighborhood well. In The Girl in Blue, ch. 10 (1970), Jerry West lives “in one of the streets off the King’s Road.”

Columbine (p. 60)

A young female character from the Italian commedia and English pantomime, the girlfriend of Harlequin.

the secret of a happy and successful life (p. 60)

Many of Wodehouse’s characters use similar phrases when giving advice:

“Always pop across streets. It is the secret of a happy and successful life.”

Psmith in Leave It to Psmith, ch. 6.5 (1923)

But it so happened that Rollo’s mother had recently been reading a medical treatise in which an eminent physician stated that we all eat too much nowadays, and that the secret of a happy life is to lay off the carbohydrates to some extent.

“The Awakening of Rollo Podmarsh” (1923; in The Heart of a Goof, 1926)

“If you want to know the secret of a happy and successful life, Barmy, old man, it is this: Keep away from parsons’ daughters.”

Pongo in “Tried in the Furnace” (1935; in Young Men in Spats, UK edition, 1936)

“The secret of a happy and successful life is to know when things have got too hot and cut your losses.”

Galahad Threepwood in Pigs Have Wings, ch. 10.2 (1952)

“Cut women out of your life, Phipps, and you will be a better, brighter man. It is the secret of a happy and prosperous career.”

Mervyn Potter in Barmy in Wonderland, ch. 13 (1952)

It was a favourite dictum of the late A. B. Spottsworth … that the secret of a happy and successful life was to get rid of the women at the earliest possible opportunity.

Ring for Jeeves/The Return of Jeeves, ch. 8 (1953/54)

“Always watch snails,” said Mortimer Bayliss approvingly. “It is the secret of a happy and successful life. A snail a day keeps the doctor away.”

Something Fishy/The Butler Did It, ch. 20 (1957)

I had long since learned that the secret of a happy and successful life was to steer clear of any project masterminded by that young scourge of the species.

Bertie speaking of Stiffy Byng in Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 5 (1963)

A.W.O.L. (p. 60)

A military abbreviation for Absent Without Leave.

Barribault’s (p. 61)

See Ice in the Bedroom.

grillroom (p. 61)

An informal restaurant, specializing in steaks, chops, and the like.

you look like Helen of Troy (p. 61)

Others whose beauty is compared to “the face that launched a thousand ships” (see The Girl in Blue):

This girl before him was marvellous. Helen of Troy could have been nothing to her.

Sam Shotter’s opinion of Kay Christopher in Sam the Sudden, ch. 12.3 (1925)

Confronted with this girl, Cleopatra would have looked like Nellie Wallace, and Helen of Troy might have been her plain sister.

Lancelot Mulliner’s opinion of Angela, daughter of the Earl of Biddlecombe, in “Came the Dawn” (1927; in Meet Mr. Mulliner, 1927/28)

“Oh, Gertrude. … She begins where Helen of Troy left off.”

Catsmeat speaking of Gertrude Winkworth in The Mating Season, ch. 7 (1949)

“My wife,” A. B. Spottsworth had said, indicating the combination of Cleopatra and Helen of Troy by whom he was accompanied…

Ring for Jeeves, ch. 1/The Return of Jeeves, ch. 5 (1953/54)

“You’re more the Helen of Troy type. Not that Helen of Troy was in your class. You begin where she left off.”

Biff Christopher to Gwendoline Gibbs in Frozen Assets/Biffen’s Millions, ch. 4.2 (1964)

“…why, you begin where Helen of Troy left off.”

Bill Hollister to Jane Benedick in Something Fishy/The Butler Did It, ch. 11 (1957)

“Dash it all, Johnny, Linda Gilpin isn’t the Queen of Sheba.”

“Yes, she is.”

“Or Helen of Troy.”

“Yes, she is, and also Cleopatra.”

A Pelican at Blandings, ch. 8.2 (1969)

anachronistic parasite on the body of the state (p. 61)

“We know what lords are. Anachronistic parasites on the body of the state, is the kindest thing you can say of them.”

Lord Ickenham, in Cocktail Time, ch. 9 (1958)

bloodsuckers (p. 61)

Various characters use this term to describe creditors, sponging relatives, and tax collectors, but the Communist perspective on the aristocracy brings this to mind:

“Look at the tall thin one with the face like a motor-mascot. Has he ever done an honest day’s work in his life? No! A prowler, a trifler, and a blood-sucker!”

Bingo Little (in disguise) haranguing Bertie in “Comrade Bingo” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

five Christian names (p. 62)

As far as I am aware, we only learn three of them: Frederick Altamont Cornwallis.

coronet hanging on a peg (p. 62)

A small crown made of gilt silver with a cap of crimson velvet trimmed with ermine, part of the official regalia of an earl; the golden band is decorated with eight tall points with ball finials and with strawberry leaves between the points. Lord Ickenham would no doubt have treated it with more care than to hang it on a hat rack.

A small crown made of gilt silver with a cap of crimson velvet trimmed with ermine, part of the official regalia of an earl; the golden band is decorated with eight tall points with ball finials and with strawberry leaves between the points. Lord Ickenham would no doubt have treated it with more care than to hang it on a hat rack.

a younger son, a mere honorable (p. 62)

The style “The Honourable” is given to younger sons of earls, as well as the sons and daughters of viscounts and barons. Informally abbreviated “hon.” and used as a noun in his next speech here, also in ch. 12 (p. 257).

Debrett (p. 62)

go into dinner behind the Vice-Chancellor (p. 62)

The rules of precedence for social events are complicated enough that reference books such as Debrett’s are essential tools for those in society.

I see no objection to earls. A most respectable class of men they seem to me. And one admires their spirit. I mean, while some, of course, have come up the easy way, many have had the dickens of a struggle starting at the bottom of the ladder as mere Hons., having to go in to dinner after the Vice-Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and all that sort of thing. Show me the Hon. who by pluck and determination has raised himself from the depths, step by step, till he has become entitled to keep a coronet on the hat peg in the downstairs closet, and I will show you a man of whom any author might be proud to write.

“Put Me Among the Earls” (in Punch, June 9, 1954, and in America, I Like You, 1956; also as “Bring On the Earls” in Over Seventy, 1957)

jerked soda (p. 62)

The verb jerk, a colloquial Americanism for dispensing drinks by pulling a lever handle, dates from 1868. The noun soda-jerker is cited from 1883 in the OED and defined as one who mixes and sells soft drinks. Wodehouse is cited from Louder and Funnier (1932) as using the hyphenated noun.

Horatio Alger (p. 63)

See Ice in the Bedroom.

SOS (p. 63)

A telegraphic distress call; see Summer Lightning. The US edition has it properly spelled without periods as above; the UK first edition (p. 55) has it as “S.O.S.” which is incorrect.

truite bleue (p. 64)

A French dish of very fresh trout cooked with vinegar, which turns the fish’s skin a metallic blue in color. [IM/LVG]

part brass rags (p. 65)

See Very Good, Jeeves.

Hants (p. 66)

Classical abbreviation for Hampshire, used in postal addresses. Derives from Old English Hantescire as used in the Domesday Book.

Tatler (p. 66)

A glossy British monthly magazine emphasizing society, fashion, lifestyle, and entertainment; founded 1901, and since the 1980s owned by Condé Nast Publications. It takes its name from an 18th-century journal published by Richard Steele with Jonathan Swift and Joseph Addison, but has no direct connection to it.

under the ether (p. 66)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

Reminiscences … to pay for their publication (p. 67)

Unlike Galahad Threepwood’s reminiscences, which promised to be a moneymaker for Lord Tilbury until withdrawn by their author, Sir Aylmer seems to have needed to use a “vanity press” arrangement. In Summer Moonshine (1937), Sir Buckstone Abbott’s My Sporting Memories are similarly published at his expense.

head on a charger (p. 68)

Here a charger is a large service plate; see Biblia Wodehousiana for the Scriptural allusion to John the Baptist.

persona grata (p. 68)

Latin: a welcomed or acceptable person.

a cat on hot bricks (p. 69)

See The Girl in Blue.

Edwin Smith of 11 Nasturtium Road, East Dulwich (p. 69)

See Very Good, Jeeves.

the big four (p. 70)

A nickname for the superintendents of the Criminal Investigation Department at Scotland Yard.

wandered into a Turkish bath on ladies’ night (p. 70)

I should imagine that if you happened to wander by accident into the steam room of a Turkish bath on Ladies’ Night, you would have emotions very similar to those I was experiencing now.

Much Obliged, Jeeves/Jeeves and the Tie That Binds, ch. 13 (1971)

It had Alice’s jewels in it (p. 71)

Reminiscent of the plot device of “The Adventure of the Six Napoleons” by Arthur Conan Doyle (1904; in The Return of Sherlock Holmes, 1905).

“dash my wig and buttons” (p. 71)

A phrase used to give the effect of swearing without using profane language. See Brewer, Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (1898 edition, p. 332).

“Well, dash my wig and buttons!” exclaimed Lord Uffenham, looking like a sibyl about to prophesy.

Money in the Bank, ch. 24 (1942)

the boys in the back room (p. 72)

See Heavy Weather. That note was written for a book published before 1939; for the present book, the allusion might be to the 1939 song or to the older popular phrase.

when Pongo and I started out last spring for Blandings Castle in the roles of Sir Roderick Glossop, the brain specialist, and his nephew Basil (p. 72)

Recounted in Uncle Fred in the Springtime (1939).

Part Two

Five

Runs from pp. 77 to 92 in US first edition.

deserving poor (p. 77)

A very Victorian concept of charity, requiring adherence to “middle-class morality” among the impoverished in order that they deserve to receive charity. Shaw lampoons this in Pygmalion in the voice of Alfred Doolittle.

“No,” I said, “take it away; give it to the deserving poor. I shall never wear it again.”

“Aunt Agatha Takes the Count” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

wearing as he did a pink shirt and a slouch hat which should long ago have been given to the deserving poor, Mr. Carmody was not much of a spectacle…

Money for Nothing, ch. 10.1 (1928)

“And I,” said Myrtle, “have got to take a few pints of soup to the deserving poor.”

“Anselm Gets His Chance” (1937; in Eggs, Beans and Crumpets, 1940)

Swooping down on Horace’s flat … Valerie Twistleton had scooped up virtually his entire outfit and borne it away in a cab, to be given to the deserving poor.

Uncle Fred in the Springtime, ch. 4 (1939)

“Lady Constance has pinched [Lord Emsworth’s] favorite hat and given it to the deserving poor, and he lives in constant fear of her getting away with his shooting jacket with the holes in the elbows.”

Service With a Smile, ch. 2.3 (1961)

mignonette (p. 77)

A garden plant, Reseda odorata, with fragrant yellow-white flowers, native to North Africa. Wodehouse mentions it one other time:

There came to Bingo, listening to these words, the illusion that a hidden orchestra had begun to play soft music, while somewhere in the room he seemed to smell the scent of violets and mignonette.

“The Word in Season” (in A Few Quick Ones, 1959)

but the word also refers to one of Anatole’s classic dishes, Mignonette de Poulet Petit Duc, named in several books beginning with The Code of the Woosters, and the houseboat in Summer Moonshine (1937) is named the Mignonette as well.

counting her blessings one by one (p. 77)

This could allude to one of several popular hymns and spiritual songs using this phrase.

Cheltenham with its gay society (p. 77)

Almost certainly meant ironically. Wodehouse’s parents had retired there in 1905, and it is mentioned in Something Fishy/The Butler Did It, ch. 2 (1957) and in Frozen Assets/Biffen’s Millions, ch. 7 (1964) as the home of couples retired from government or military service.

a consummation always devoutly to be wished (p. 78)

Paraphrasing Hamlet’s most famous soliloquy: see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

his wealth being a burly spear and brand… (p. 78)

From the song “Hybrias the Cretan” (lyric by Thomas Campbell, translated from Greek; music by J. W. Elliott).

Campbell’s lyric at Google Books.

Sheet music online at the National Library of Australia.

Wodehouse himself sang this song at a Dulwich College concert in 1899, and in the UK edition of The Prince and Betty, ch. 5 (1912), John Maude says:

I haven’t felt such a fool since I sang ‘Hybrias the Cretan’ at the school concert.

a bit of goose (p. 78)

the sleeve across the windpipe (p. 78)

See The Mating Season.

smoking a somber pipe (p. 79)

An example of one of Wodehouse’s favorite literary devices, the transferred epithet.

unpleasant things to an odalisque with a bowstring (p. 79)

“I don’t know if you happen to know it, but in Turkey all this insubordinate stuff, these attempts to dictate to the master of the house and the head of the family, would have led long before this to you being strangled with bowstrings and bunged into the Bosporus.”

Esmond Haddock to his aunts in The Mating Season, ch. 26 (1949)

Barmy was robbed of speech, and Mr. Lippincott, his task completed, was now preparing to relax, like an executioner in some Oriental court taking a breather after strangling a few Odalisques with his bowstring.

Barmy in Wonderland, ch. 19 (1952)

He realized how a good-hearted executioner at an Oriental court must feel after strangling an odalisque with a bowstring.

Pigs Have Wings, ch. 4.3 (1952)

drooping his lower jaw (p. 81)

Only instances of drooping are listed here; there are many other places where lower jaws have fallen or are hitched up.

His lower jaw drooped feebly, like a dying lily.

Blair Eggleston in Hot Water, ch. 2.4 (1932)

He polished his shoes with one of the sofa-cushions, and took his hat from the table where he had placed it and gave it another brush: but after that there seemed to be nothing in the way of intellectual occupation offering itself, so he just leaned back in a chair and unhinged his lower jaw and let it droop, and sank into a sort of coma.

Mervyn Mulliner in “The Knightly Quest of Mervyn” (in Mulliner Nights, 1933)

Lord Shortlands, allowing his lower jaw to droop restfully, gave himself up to meditation.

Spring Fever, ch. 5 (1948)

“Gussie gave me that same sense of hopeless desolation. He sat there with his lower jaw drooping, goggling at me like a codfish—”

Catsmeat in The Mating Season, ch. 3 (1949)

Mr. Anderson … was regretting that the latter’s extraordinary wealth made it impossible for him to hurl at Barmy’s head the silver presentation inkpot on his desk, to teach him not to let his lower jaw droop like that.

Barmy in Wonderland, ch. 2 (1952)

He stood staring, his lower jaw drooping on its hinge.

Jerry Vail in Pigs Have Wings, ch. 10.3 (1952)

“Even today I’m about as announced an oaf as ever went around with his lower jaw drooping and a glassy look in his eyes, but you have literally no conception what I was like in my early twenties.”

Wodehouse speaking in Bring On the Girls, ch. 14.5 (US edition, 1953)

“Yes, I distinctly recall a greenish pallor and a drooping lower jaw.”

Monica Carmoyle, about Bill Belfry in Ring for Jeeves/The Return of Jeeves, ch. 9 (1953/54)

All you can do is stand with your lower jaw drooping like a tired lily, looking a priceless ass, and that is what Stilton was doing now.

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 17 (1954)

…it was through a sort of mist that he stared pallidly at his companion, his eyes wide, his lower jaw drooping, perspiration starting out on his forehead as if he were sitting in the hot room of a Turkish bath.

Sir Raymond Bastable in Cocktail Time, ch. 4 (1958)

At an early point in these remarks Oofy’s lower jaw had drooped like a tired lily.

“The Fat of the Land” (in A Few Quick Ones, 1959)

“Why, hullo,” she proceeded, seeing that Kipper was slumped back in his chair trying without much success to hitch up a drooping lower jaw.

Aunt Dahlia in Jeeves in the Offing, ch. 13 (1960)

By standing on one leg and allowing his lower jaw to droop Freddie indicated that he would be delighted to do so.

Ice in the Bedroom, ch. 2 (1961)

He would, as he had rather suspected he would, congeal in every limb like a rabbit confronted with a boa constrictor and stand staring with his lower jaw drooping to its fullest extent, fearing the worst.

Horace Appleby in Do Butlers Burgle Banks?, ch. 8 (1968)

Though of a dreamy temperament and inclined in most crises to sit still and let his lower jaw droop, he could on occasion be the man of action.

Lord Emsworth in A Pelican at Blandings, ch. 10.1 (1969)

trinitrotoluol (p. 82)

See A Damsel in Distress.

as if he had been stuffed by a good taxidermist (p. 83)

See Summer Lightning.

beat about bushes (p. 83)

To circle round an uncomfortable topic rather than bringing it up directly.

against the public weal (p. 83)

Causing harm to the general welfare of a country or society.

Giuseppe … looked like one of the executive staff of the Black Hand plotting against the public weal.

The Small Bachelor, ch. 16.1 (1927)

Lady Bostock’s eyes were already bulging … protrude a little further. (p. 83)

See Thank You, Jeeves.

the sixteenth inst. (p. 84)

The sixteenth day of the present month; short for instant. An abbreviation commonly used in commercial correspondence as well as legal testimony.

Mark the sequel (p. 85)

Wodehouse often quoted this phrase from Falstaff in The Merry Wives of Windsor; see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

bona fides (p. 85)

Bona fides, treated as a plural noun, has acquired the meaning “proofs of good faith” in English. [MH]

gasper (p. 86)

Slang for a cigarette, especially an inexpensive or harsh one. First OED citation is from Isis, an Oxford University student magazine, in 1914.

dog races down Shepherd’s Bush way (p. 86)

In West London, between Hammersmith and North Kensington. Greyhound racing began in 1926 at the White City Stadium there, originally built for the 1908 Summer Olympics.

lighted matches between his toes (p. 88)

The first of many speculations of this nature in Wodehouse; see The Old Reliable.

young poop (p. 89)

See Summer Lightning.

Six

Runs from pp. 93 to 123 in US first edition.

boomps-a-daisy (p. 93)

See The Mating Season.

pie-faced (p. 93)

See Very Good, Jeeves.

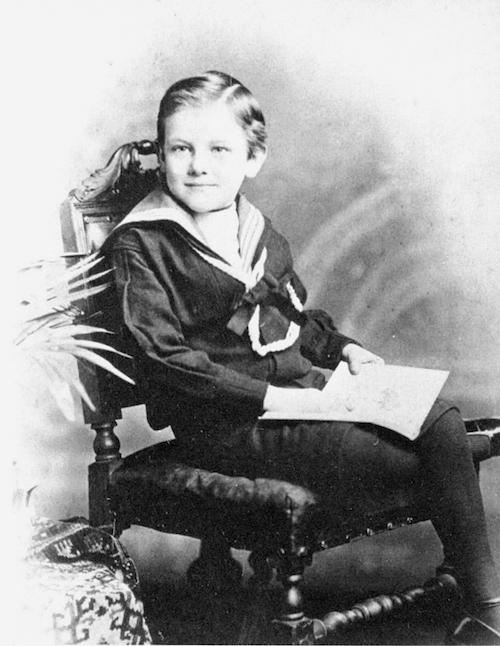

looked sweet in a sailor suit (p. 94)

looked sweet in a sailor suit (p. 94)

That could certainly be said of the young Plum, age about seven, in the image at right.

mangoldwurzel (p. 94)

Spelled mangel-wurzel in UK editions. See Young Men in Spats.

our afternoon at The Cedars (p. 95)

Recounted in “Uncle Fred Flits By” (1935; in Young Men in Spats, 1936).

a super supporting a star (p. 97)

Short for “supernumerary”—theatrical term for what in films is called an extra: a player who fills out a crowd scene, but has no individual lines to speak nor a character name. [MH]

a pippin of a girl (p. 97)

From the sense of “pippin” as a sweet dessert apple, the further meanings of “a dear young girl” and “an excellent thing, a pleasing example of its kind” were derived.

“We are amused?” (p. 98)

The use of the “royal we” may be an allusion to a phrase often attributed to Queen Victoria: “We are not amused.” See The Girl in Blue.

“Nerves vibrating?” (p. 98)

See the discussion of vibrating ganglions in Sam the Sudden.

like a watered flower (p. 101)

Claude had revived like a watered flower, but he nearly had a relapse when he saw his bally brother goggling at him over the bed-rail.

“The Delayed Exit of Claude and Eustace” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

It was as good a dinner as I have ever absorbed, and it revived Uncle Thomas like a watered flower.

“Clustering Round Young Bingo” (1925; in Carry On, Jeeves, 1925/27)

He paused, and in the background Pongo revived like a watered flower.

Uncle Fred in the Springtime, ch. 11 (1939)

Bill revived like a watered flower.

Ring for Jeeves/The Return of Jeeves, ch. 6 (1953/54)

During this halcyon period, if halcyon is the word I want, it would not be too much to say that I revived like a watered flower.

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 8 (1954)

Horace revived like a watered flower.

Do Butlers Burgle Banks?, ch. 9.2 (1968)

tidings of great joy (p. 101)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

skip like the high hills (p. 101)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

somnambulist (p. 102)

sleepwalker

Well met by moonlight (p. 102)

Adapted from A Midsummer Night’s Dream: see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

Bloody awful (p. 102)

The adjective bloody used as an intensifier has long been considered impolite or sacrilegious in Britain; Shaw created a minor furore by putting “Not bloody likely!” in Eliza Doolittle’s mouth in Pygmalion (1914).

In his earlier works, Wodehouse often used euphemistic substitutes such as ruddy or crimson for it; the word begins appearing in his works in Money in the Bank (1942). Richard Usborne (A Wodehouse Companion) suggests that Wodehouse’s exposure to the all-male environment of the internment camp accounts for the occurrence of such phrases as “bloody awful” and “too bloody much” in this and later books.See also to hell with below.

roses, roses all the way (p. 103)

See Bill the Conqueror.

old buster (p. 103)

off his onion (p. 103)

See Sam the Sudden.

sticking straws in his hair (p. 103)

See Bill the Conqueror.

potty (p. 104)

In the sense of “crazy, mad, eccentric” the OED has citations beginning in 1920.

one of those hollow, mirthless laughs (p. 104)

See A Damsel in Distress.

singing like a lark (p. 104)

Bill’s attitude is opposite of that of Mr. Duff:

“And when she bust our engagement I went around singing like a lark.”

Quick Service, ch. 18 (1940)

Casanova (p. 105)

the head upon which all the sorrows of the world have come (p. 105)

See Summer Lightning.

hideous vengeance (p. 106)

See Very Good, Jeeves.

forty-two years (p. 106)

Lord Ickenham’s age is established here at sixty years.

the milk of human kindness (p. 107)

Quoting Lady Macbeth: see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

chew broken glass (p. 107)

“…the Rev. J. G. Smethurst, the ruling spirit of Harborough, was a man who chewed broken bottles and devoured his young.”

“The Voice from the Past” (1931; in Mulliner Nights, 1933)

“There’s a fellow who chews broken glass and drives nails into the back of his neck instead of using a collar stud!”

Bertie speaking of Pop Stoker in Thank You, Jeeves, ch. 13 (1934)

[Sir Rackstraw Cammarleigh] “is a man who chews tenpenny nails and swallows broken bottles”

“The Code of the Mulliners” (1935; in Young Men in Spats, 1936)

Aunt Agatha, who eats broken bottles and wears barbed wire next to the skin…

The Code of the Woosters, ch. 1 (1938)

“Abe Erlanger … eats broken bottles and conducts human sacrifices at the time of the full moon, but he’s a thoroughly good chap.”

Bring On the Girls, ch. 3 (US edition, 1953)

“If he eats chocolate bars, he can’t be the type of employer who chews broken glass and tenpenny nails and is ferocious with those on his payroll.”

Company for Henry, ch. 9.3 (1967)

conduct human sacrifices at the time of the full moon (p. 107)

“I strongly suspected my headmaster of conducting human sacrifices behind the fives-courts at the time of the full moon,” said the Tankard.

“The Voice from the Past” (1931; in Mulliner Nights, 1933)

“Monty Bodkin strongly suspects that she [Lady Constance] conducts human sacrifices at the time of the full moon.”

Uncle Fred in the Springtime, ch. 8 (1939)

…aunt Agatha … being my tough aunt, the one who eats broken bottles and conducts human sacrifices by the light of the full moon.

Joy in the Morning, ch. 1 (1946)

my Aunt Agatha, who is known to devour her young and conduct human sacrifices at the time of the full moon

Jeeves in the Offing, ch. 12 (1960)

Brabazon-Plank (p. 108)

This is the first time we hear the full hyphenated surname of Major Plank. The name Brabazon carries aristocratic overtones, as in a line of Barons of the UK and a line of Irish Baronets. Wikipedia has links to more notables of this name.

broad in the beam (p. 108)

Derived from nautical terminology, in which a boat’s beam is its widest side-to-side measurement; figuratively applied to a person’s width of the hips or buttocks. The earliest OED citation of the phrase in this sense is from 1944; the present sentence seems to be Wodehouse’s only use of it.

Bimbo (p. 108)

See Leave It to Psmith.

pluck the gowans fine (p. 108)

the intellectual pressure of the conversation (p. 109)

See A Damsel in Distress.

resemblance to a fish on a slab (p. 109)

“at The Cedars … I impersonated” (p. 110)

Recounted in “Uncle Fred Flits By” (1935; in Young Men in Spats, 1936).

a young man’s crossroads (p. 110)

A point in life where a significant decision is required.

“The old choice between Pleasure and Duty, Comrade Adair. A Boy’s Cross-Roads.”

“The Lost Lambs”, ch. 7 (1908; later in Mike, 1909, and Mike and Psmith, 1953)

And yet he hated the idea of meekly allowing that two thousand pounds to escape from his clutch.

A young man’s crossroads.

Leave It to Psmith, ch. 1.4 (1923)

I didn’t like the prospect of being collared by Aunt Agatha, but on the other hand I simply barred the notion of leaving Roville by the night-train and parting from Aline Hemmingway. Absolutely a man’s cross-roads, if you know what I mean.

“Aunt Agatha Takes the Count” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

Roscoe plucked at his double chin, debating within himself what to do for the best. And as he sat there at a young man’s crossroads, Mortimer Bayliss sauntered in.

Something Fishy/The Butler Did It, ch. 4 (1957)

I had never gone much into the family history, but I assumed that my ancestors, like everybody else’s, had done well at Crecy and Agincourt, and nobody likes to be a degenerate descendant. I was at a young man’s crossroads.

Over Seventy, ch. 2 (1957), and in PGW’s commentary to a letter dated October 12, 1949 in Author! Author! (1962)

to call myself Robinson (p. 110–111)

George Robinson, Uncle Fred’s alias at the dog races, as mentioned in chapter 4 (p. 69 of the US edition).

cynosure of all eyes (p. 111)

Cynosure (Greek “tail of the dog”) originally referred to the constellation of Ursa Minor in the northern sky, around whose tail tip (Polaris, the North Star) all other stars appear to revolve. The figurative sense of “center of all attention” derives from this.

in the bag (p. 111)

See Hot Water.

the shape of things to come (p. 111)

This phrase about the future was originally the title of a 1929 book of science fiction by H. G. Wells, the basis for the 1936 British film Things to Come.

paled beneath his tan (p. 112)

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

Stiffen the sinews, summon up the blood. (p. 112)

From King Henry V: see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

passed through the furnace (p. 112)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

frigidaire (p. 112)

Wodehouse is using a trademark (see Summer Moonshine) as if it were a generic name for a refrigerator.

A man so recently come from the society of that Spirit of Frigidaire was not easily to be frozen by lesser freezers; and though Jane’s eye was keen, it was not in the Whittaker class.

Summer Moonshine, ch. 12 (1937)

Chatting with Augustus Fink-Nottle without Corky was like getting the inside from Mark Antony on the topic of Cleopatra, and every second he spent out of the frigidaire was fraught with peril.

The Mating Season, ch. 14 (1949)

“No, I won’t,” she replied in a voice straight from the frigidaire, “because I’m jolly well not going there.”

Jill Wyvern in Ring for Jeeves/The Return of Jeeves, ch. 19 (1953/54)

“Bertie,” she said in a voice straight from the frigidaire, “will you do me a favour?”

Jeeves in the Offing, ch. 12 (1960)

It was as though he had been for an extended period shut up in a frigidaire with the first Queen Elizabeth.

A Pelican at Blandings, ch. 8.2 (1969)

It is one thing to take down letters in shorthand, with her skill at which he had long been familiar, and quite another to raid your employer’s frigidaire for Bavarian cream after dark.

Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin, ch. 5.2 (1972)

an eye like that of a codfish (p. 113)

“Ike Goble … has a greasy soul, a withered heart, and an eye like a codfish.”

Jill the Reckless/The Little Warrior, ch. 15.2 (1920)

His eyes, peering through gold-rimmed glasses, protrude slightly, giving him something of the dumb pathos of a codfish.

Bailey Bannister in The White Hope/The Coming of Bill, ch. 2 (1914/20)

protecting juju (p. 113)

In some spiritual or religious traditions of Africa, an object with magical powers, or the supernatural powers which can be called upon with the aid of that object.

made of sterner stuff (p. 113)

Alluding to Marc Antony in Julius Caesar; see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

bright and bounding (p. 113)

“The top of the morning to you, my bright and bounding J. G.”

Barmy in Wonderland, ch. 1 (1952)

“Tell me all your news, my bright and bounding barrister.”

Lord Ickenham in Cocktail Time, ch. 2 (1958)

“Hello, my bright and bounding Phipps,” she said.

The Old Reliable, ch. 21 (1951)

pourparlers (p. 114)

French: informal discussions preliminary to actual negotiations. [TM]

giving up his water ration to the sick and ailing (p. 115)

Wodehouse usually invokes the story of Sir Philip Sidney regarding this action; see Sam the Sudden.

encouraging … the weaker brethren (p. 115)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Chilled-Steel Oakshott (p. 115)

Slimmo (p. 115)

Slimmo will return as a significant plot point in Pigs Have Wings (1952).

callipygous (p. 115)

Having prominent or beautifully-shaped buttocks; a borrowing from Greek. Though the term has a classical sound, the OED cites its first English use in Aldous Huxley’s Antic Hay (1923); the next citation is the present sentence from Wodehouse.

given me the office (p. 115)

From the use of “office” as a term for a liturgy in Christian churches, often including statements from the celebrant and responses by the congregation, the figurative colloquial meaning has arisen, meaning to give a hint or a cue that calls for a response.

“Good evening, miss,” said Jeeves in his suave way. “Miss Pirbright, sir,” he added, giving me the office in an undertone.

The Mating Season, ch. 24 (1949)

tidings of great joy (p. 116)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

swept and garnished (p. 117)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

We shall all meet, then, at Philippi (p. 117)

Alluding to Cassius in Julius Caesar; see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

Something attempted, something done (p. 118)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

the easy repose of a red Indian at the stake (p. 118)

like Caesar in his tent the day he overcame the Nervii (p. 118)

Alluding to Marc Antony in Julius Caesar; see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

look for the silver lining (p. 119)

See Bill the Conqueror.

Paynim (p. 119)

A general term for the pagans/Mohammedans etc. against whom the Crusaders fought from the 11th to 13th centuries. [NTPM]

life-giving fluid (p. 120)

Beer, here and in Pigs Have Wings, but sometimes something stronger.

The suggestion he conveyed was that just one more whack at the life-giving fluid would have had him balancing the weapon on the tip of his nose.

Soapy Molloy, after a couple of shots of brandy in Money in the Bank, ch. 27 (1942)

“Hey!” said Sir Gregory, when a few minutes later the butler returned with the life-giving fluid.

Pigs Have Wings, ch. 6.2 (1952)