Thank You, Jeeves

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

This is part of an ongoing effort by the members of the Blandings Yahoo! Group to document references, allusions, quotations, etc. in the works of P. G. Wodehouse.

Thank You, Jeeves was originally annotated by Mark Hodson (aka The Efficient Baxter). The notes have been reformatted somewhat and extended by other members of the group, notably Neil Midkiff [NM in notes below] and Ian Michaud [IM], but credit goes to Mark for his original efforts, even while we bear the blame for errors of fact or interpretation.

Thank You, Jeeves was serialized in the Strand magazine, August 1933 through February 1934, and in Cosmopolitan magazine, January through June 1934. In book form, it was published by Herbert Jenkins in the UK on 16

April 1934 (left) and as Thank You, Jeeves! by Little, Brown in the US on 23 April 1934 (right). For once, both

used the same title other than the exclamation point (which had appeared in both magazine serials).

Thank You, Jeeves was serialized in the Strand magazine, August 1933 through February 1934, and in Cosmopolitan magazine, January through June 1934. In book form, it was published by Herbert Jenkins in the UK on 16

April 1934 (left) and as Thank You, Jeeves! by Little, Brown in the US on 23 April 1934 (right). For once, both

used the same title other than the exclamation point (which had appeared in both magazine serials).

See Neil Midkiff’s novel page for an overview on the differing versions of the text. The Cosmopolitan serial generally follows US spellings; the other three versions are similar to each other in spelling, with the UK style in honour and neighbour but the US style in realize and recognize.

Chapter titles are found only in the UK book editions.

Page references in these notes are based on the 1999 Penguin edition; page numbers with ? are approximate locations for newly inserted notes.

Notes

Preface

Written for the 1975 Barrie & Jenkins edition

As Wodehouse says, Thank You, Jeeves was the first full-length novel featuring Jeeves and Bertie. They had previously appeared in the story collections My Man Jeeves (1919), The Inimitable Jeeves (1923), Carry On, Jeeves! (1925). and Very Good, Jeeves! (1930).

Miss Spelvin

The poet Rodney Spelvin was reformed by golf in three stories in 1924–5, but suffered a relapse in 1949. [Also, in Summer Moonshine, the first husband of the Princess von und zu Dwornitzchek was a Mr. Spelvin, Elmer Chinnery’s partner in the glue business. In theatrical circles, “George Spelvin” is a common pseudonym for an actor who doesn’t want to be credited in the program under his own name. —NM] [There was also an off-stage Doctor Spelvin in “The Luck of the Stiffhams.” —IM]

Lord Jasper Murgatroyd

Murgatroyd was a name Wodehouse often used for characters mentioned in passing – it is one of those names that seems to fit equally well to aristocrats (the style “Lord Jasper Murgatroyd” implies that he is the younger son of a duke) or to butlers and stablemen. The only important character called Murgatroyd is the red-haired Mabel.

[But see “The Kind-Hearted Editor” for another reference to the character name. Wodehouse’s Jaspers are often baronets and usually heavies, whether financiers like Sir Jasper Addleton (“The Smile that Wins”) and Sir Jasper Todd (“Big Business”), wicked guardians like Sir Jasper ffinch-ffarrowmere (“A Slice of Life”), or just evildoers like Sir Jasper Murgleshaw (“The Baronet’s Redemption”). —NM]

Murgatroyd is originally a West Yorkshire name. The place formerly known as Moorgateroyd lies near Luddendenfoot in Calderdale (a “royd” was a clearing in a wood).

Baronets called Murgatroyd appear most famously in Gilbert & Sullivan’s Ruddigore, or the Witch’s Curse (1887). Sir Jasper (3rd Baronet) is listed as one of the ghosts in the famous picture gallery scene, although he doesn’t have an individual speaking part.

Daniel H. Garrison: Who’s Who in Wodehouse (1991)

Wikipedia article on Murgatroyd family

https://gsarchive.net/ruddigore/libretto.txt

And so the long day wore on.

machines … recorded on wax

Rosie M. Banks writes her stories this way – see “Clustering Round Young Bingo” (1925).

like the Ancient Mariner when he got rid of the albatross

See Cocktail Time.

hemispheres … corpus collosum [sic]

In human beings, the left hemisphere of the brain is dominant in analytical tasks and language, and controls the right side of the body; the right hemisphere is specialised in things like spatial tasks and emotion, and controls the left side of the body. Presumably the implication is that the construction of the plot is a right-hemisphere task, but writing the text belongs to the left hemisphere.

As Wodehouse says, the corpus callosum (the correct spelling) handles most communication between the two. If it is damaged, then the two hemispheres of the brain act somewhat independently of each other. This was established in some famous experiments on cats performed by Nobel laureate Roger Sperry in the early 1960s; Wodehouse presumably wrote this preface around the time that Sperry’s work was published. [The preface first appeared in the 1975 Barrie & Jenkins edition. —NM]

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aso/databank/entries/bhsper.html

Oh, what a noble mind is here o’erthrown

This is Ophelia, talking about the supposedly-mad Hamlet, who has just told her to go into a nunnery. It is perhaps a little harder for us to think of Wodehouse as “The glass of fashion and the mould of form.”

O! what a noble mind is here o’erthrown:

The courtier’s, soldier’s, scholar’s, eye, tongue, sword;

The expectancy and rose of the fair state,

The glass of fashion and the mould of form,

The observ’d of all observers, quite, quite down!

And I, of ladies most deject and wretched,

That suck’d the honey of his music vows,

Now see that noble and most sovereign reason,

Like sweet bells jangled, out of tune and harsh;

That unmatch’d form and feature of blown youth

Blasted with ecstasy: O! woe is me,

To have seen what I have seen, see what I see!

William Shakespeare (1564–1616): Hamlet III:i, 132–143

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for more references to this passage.

proposer and seconder

In exclusive clubs, a motion to admit a new club member must be proposed and seconded by two existing members. [NM]

Chapter 1

Jeeves Gives Notice

Runs from pp. 1 to 10 in the 1999 Penguin edition

banjolele (Ch.1; page 1)

The banjolele or banjo-ukulele is a hybrid instrument that first appeared in 1918, the first type being patented by Alvin D. Keech (Keech used the trade-name “Banjulele,” so later imitators had to come up with new variants of the name). Banjoleles are tuned and strung like ukuleles, with four gut strings, but they have a hoop with vellum stretched over it, like a banjo, thus allowing them to produce a louder sound than a standard ukulele. (There’s a lot of American history in this instrument – the banjo was developed from their traditional instruments by African slaves and the ukulele by Hawaian islanders.)

The instrument was made famous in particular by George Formby (1904–1961), probably the most successful British entertainer of the thirties and forties. It is difficult to imagine the fastidious Bertie singing Formby’s suggestive lyrics, though...

Ignatius Mulliner, “The Man Who Gave Up Smoking,” plays “Old Man River” on a standard ukulele.

The third of the links below takes you to a picture of Mike Skupin playing the banjolele at a Wodehouse convention in the USA.

https://www.georgeformby.co.uk/georgeformby-obe.htm

https://www.theukuleleman.com/page8.html

https://madameulalie.org/images/skupin-banjolele.jpg

J. Washburn Stoker (Ch.1; page 1)

Phelps notes that Wodehouse’s lawyer at the time of his tax actions of 1948–51 was Watson Washburn. It’s not clear if he was already acting for Wodehouse in 1934. [Yes, it seems that he was. McCrum: Wodehouse: A Life, p.219; 1933 correspondence from agent Reynolds to Wodehouse mentioning Washburn, in McIlvaine N46.25, N46.31. —NM]

Stoker might have been named for the 19th century American wire manufacturer and philanthrophist, Ichabod Washburn, founder of Washburn University.

Barry Phelps: P. G. Wodehouse: Man and Myth (1992) 26, 190–191

“They must be over here.” (Ch.1; page 1)

Thus in both magazine serials and UK book; US book has “They must be in London.” [NM]

Old Man River (Ch.1; page 1)

Song from the musical Show Boat (1927, Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II), written for and made famous by the African-American lawyer, political activist, actor and singer, Paul Robeson (1898–1976). [In the revised version of “Big Business” from A Few Quick Ones (1959), a Small Bass at the Anglers’ Rest argues that the first word of the title is “Old” while a Light Lager prefers “Ol’.” Mr. Mulliner suggests that Mr. Oscar Hammerstein, the lyricist, preferred Ol’, and this is supported by the sheet music. —NM]

Sir Roderick Glossop (Ch.1; page 2)

The prominent nerve specialist and his daughter, Honoria, first appeared in The Inimitable Jeeves. Glossop is a town in Derbyshire. [For the full saga up to this point, read “Sir Roderick Comes to Lunch” in The Inimitable Jeeves, “The Rummy Affair of Old Biffy” and “Without the Option” in Carry On, Jeeves!, and “Jeeves and the Yule-Tide Spirit” in Very Good, Jeeves! Sir Roderick reappears in Uncle Fred in the Springtime (briefly), How Right You Are, Jeeves / Jeeves in the Offing, and “Jeeves and the Greasy Bird” in Plum Pie. —NM]

putting on the nosebag (Ch.1; page 2)

Bertie is joshing the diners at the famous grill restaurant in the Savoy Hotel by referring to the way that horses are fed their oats, from a bag literally tied around the horse’s nose. [NM]

Lord Chuffnell (Ch.1; page 2)

This seems to be a name that Wodehouse invented. It doesn’t correspond to any British placename, and I have found no reference to it on the web that is not related to this book.

Tinkler-Moulke (Ch.1; page 3)

This seems to be her only appearance in the canon.

Tinkler is a variant of “Tinker” that occurs occasionally as a British surname, Moulke is rare as a name, perhaps an anglicisation of a German name.

Sherry-Netherland (Ch.1; page 3)

Elegant New York hotel at 781 Fifth Avenue, overlooking Central Park. It was built for Louis Sherry and Lucius Boomer in 1927 (architects Schultze & Weaver) to replace the New Netherland Hotel of 1892. When it opened, the 38-storey building was the world’s tallest apartment-hotel. Some of the decoration in the lobby comes from the demolished Vanderbilt mansion.

https://www.sherrynetherland.com/

https://www.thecityreview.com/piersher.html

She got right in amongst me. (Ch.1; page 3)

Usually Wodehouse uses “got right in amongst” with respect to a person’s nervous system; see Bill the Conqueror. So this must be a way of describing the physical effect of Bertie’s attraction to Pauline. [NM]

Keats … Chapman’s Homer … Cortez (Ch.1; page 3)

Jeeves fails to point out to Bertie that Keats famously got it wrong: it was Balboa, not Cortez, who was the first European to see the Pacific Ocean from Panama.

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific—and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

John Keats (1795–1821): On first looking into Chapman’s Homer

Wodehouse had something to say about this in the preface to The Clicking of Cuthbert:

In the second chapter I allude to Stout Cortez staring at the Pacific. Shortly after the appearance of this narrative in serial form [in America], I received an anonymous letter containing the words, “You big stiff, it wasn’t Cortez, it was Balboa.” This, I believe, is historically accurate. On the other hand, if Cortez was good enough for Keats, he is good enough for me. Besides, even if it was Balboa, the Pacific was open for being stared at about that time, and I see no reason why Cortez should not have had a look at it as well.

a monkey wrench was bunged into the machinery (Ch.1; page 3?)

See Leave It to Psmith.

pot of poison (Ch.1; page 3?)

This epithet is used for a wide range of Wodehouse characters. It seems originally to have been used as a euphemism for alcoholic beverages in William Cobbett’s Cottage Economy (1824). [NM]

“The kid is a pest, a wart, and a pot of poison, and should be strangled!”

George Caffyn on Junior Blumenfield in “Jeeves and the Chump Cyril” (1918; ch. 10 of The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

[Lady Underhill] was a pest and a pot of poison…

Jill the Reckless/The Little Warrior, ch. 1.3 (1920)

“Jane,” said Archie, into the telephone, “is a pot of poison.”

“Washy Makes His Presence Felt” (1920; as ch. 21 in Indiscretions of Archie, 1921)

To me the girl was simply nothing more nor less than a pot of poison.

Bertie speaking of Honoria Glossop in “Bertie Gets Even” (1922; as ch. 5 in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

“The modern young man,” said Aunt Dahlia, “is a pot of poison and wants a nurse to lead him by the hand and some strong attendant to kick him regularly at intervals of a quarter of an hour.”

“Jeeves and the Song of Songs” (1929; in US edition of Very Good, Jeeves, 1930; replaced by “is a congenital idiot” in UK book)

Agnes Flack, he reflected, was undeniably a pot of poison; but so much the better.

“Those in Peril on the Tee” (1927; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929/30)

On the point of asking who the devil Reginald was, Sir Aylmer remembered that his daughter had recently become betrothed to some young pot of cyanide answering to that name.

Pongo Twistleton in Uncle Dynamite, ch. 3.2 (1948)

At any other moment this coarse ribaldry would have woken the fiend that sleeps in Bertram Wooster and led to the young pot of poison receiving another clout on the head, but I had no time now for attending to Thoses.

The Mating Season, ch. 18 (1949)

“The first thing he would do would be to run bleating to the Dalrymple pot of poison and spill the beans, and half an hour after that she would be round here with grapes and kind inquiries.”

Bachelors Anonymous, ch. 12 (1973)

doing down the widow and orphan (Ch.1; page 4?)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

the Wedding Glide (Ch.1; page 4)

Song, “The Wedding Glide” by Louis A. Hirsch, performed by Shirley Kellogg in “The Passing Show of 1912” (Winter Garden New York) and “Hullo, Ragtime!” (London Hippodrome).

Parlour maids and nurse maids banish their pride

Throw their arms around his neck and do the wedding glide

Louis A. Hirsch: The Wedding Glide

Sheet music, with American cover artwork

Cover artwork of British sheet music

cats and fish … stolen hat (Ch.1; page 5)

See “Sir Roderick Comes to Lunch”; also in The Inimitable Jeeves as two chapters: “Introducing Claude and Eustace/Sir Roderick Comes to Lunch”

Punctured hot water bottle (Ch.1; page 5)

See “Jeeves and the Yule-Tide Spirit” (1927; in Very Good, Jeeves, 1930).

sponge-bag trousers and gardenia (Ch.1; page 5)

Formal morning apparel suitable for a wedding, along with a flower for decoration; see explanation and illustrations of these black-and-gray-striped trousers. [NM]

the cool what’s the word to come calling (Ch.1; page 5)

Possibly “cool cheek”? Wodehouse used it from 1905 (“An International Affair”) to 1963 (Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 11) to mean audacity or effrontery. [NM]

Those who know Bertram Wooster best (Ch.1; page 5)

See The Code of the Woosters for similar phrases in which Bertie refers to himself in the third person. [NM]

Ben Bloom (Ch.1; page 5)

Ben Bloom and his Baltimore Buddies seem to be fictitious.

Alhambra (Ch.1; page 5)

See Bill the Conqueror.

the germ of dementia praecox (Ch.1; page 6)

Nowadays the term dementia is used to describe an irreversible deterioration in brain function, the result of various medical conditions (senile dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, etc.). Dementia praecox (premature dementia) was the 19th century term used for the severe personality disorders that we now call schizophrenia.

Eugen Bleuler established in 1908 that these illnesses were not linked to an irreversible brain deterioration, and introduced the new term schizophrenia to describe them more accurately. It is thus unlikely that Sir Roderick, in the 1930s, would use the term Dementia praecox. Nowadays, schizophrenia patients often respond well to antipsychotic drugs.

There doesn’t seem to be any evidence of the existence of a schizophrenia germ – modern science seems to lean more towards the idea of a schizophrenia gene.

You ought to be certified! (Ch.1; page 6)

The legal basis for the care of people with mental illnesses was established in the late nineteenth century (Lunacy Act 1890). Certifying someone insane allowed them to be detained against their will in a poor-house or asylum. The Mental Treatment Act, 1930, moved the emphasis to treatment, and provided for voluntary mental patients, so it would no longer have been necessary for Bertie to have been certified (assuming he was willing to undergo treatment).

In the current trade jargon, patients who need to be detained against their will are “sectioned” under Sections 2, 3 or 4 of the Mental Health Act 1983.

https://archive.uea.ac.uk/~wp276/MENTAL%20HEALTH%20ACT%20REFORM.htm

Shakespeare … Treasons, stratagems, and spoils (Ch.1; page 7)

In both US and UK magazine serials and in the US book, Bertie slightly misquotes Shakespeare as “the man who has not music in his soul” here. In the UK book Bertie correctly quotes it as “the man that hath no music in himself”; apparently an editor at Herbert Jenkins Ltd. took it upon himself to fix the quotation, not realizing that Bertie’s memory for this sort of thing is often faulty. At least Bertie got the iambic pentameter correct in his version! [NM]

The man that hath no music in himself,

Nor is not mov’d with concord of sweet sounds,

Is fit for treasons, stratagems, and spoils;

The motions of his spirit are dull as night,

And his affections dark as Erebus:

Let no such man be trusted. Mark the music.

Shakespeare: The Merchant of Venice V:i, 93–98

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for more references to this passage.

…pluck out the Pom which is in her own eye (Ch.1; page 7)

Pom = Pomeranian dog, of course.

1 Judge not, that ye be not judged.

2 For with what judgment ye judge, ye shall be judged: and with what

measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again.

3 And why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother’s eye, but

considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye?

4 Or how wilt thou say to thy brother, Let me pull out the mote out

of thine eye; and, behold, a beam is in thine own eye?

5 Thou hypocrite, first cast out the beam out of thine own eye; and

then shalt thou see clearly to cast out the mote out of thy brother’s eye.

Bible: Matthew 7:1–5

‘The Wedding of the Painted Doll’ (Ch.1; page 8)

Song by Arthur Freed and Nacio Herb Brown from the 1928 film Broadway Melody, the first all-singing, all-dancing Hollywood musical. This film was originally conceived as a “biopic” about the Duncan sisters, who, as Wodehouse describes in Bring On the Girls, were supposed to star in one of his shows, but went off to do Topsy and Eva instead.

Most of the songs Bertie lists in this section are still copyright. However, you can find the lyrics to most of them on the web or performances of them at youtube.com. “The Wedding of the Painted Doll” from The Broadway Melody (1929).

‘Singin’ in the Rain’ (Ch.1; page 8)

Song by Arthur Freed and Nacio Herb Brown from the 1929 film Hollywood Revue of 1929. Like “Wedding of the Painted Doll,” it was later re-used in the 1952 Gene Kelly film Singin’ in the Rain.

‘Three Little Words’ (Ch.1; page 8)

Song by Harry Ruby and Bert Kalmar, from the 1930 film “Check and Double Check”. 1930 recording by Duke Ellington and His Orchestra with the Rhythm Boys. This one was also recycled in the fifties, in the Fred Astaire film Three Little Words (1950), based on the career of Ruby and Kalmar.

‘Goodnight, Sweetheart’ (Ch.1; page 8)

Song by Ray Noble from the early 1930s. Yet again, this song came back as a hit in the fifties.

‘My Love Parade’ (Ch.1; page 8)

Song by Victor Schertzinger and Clifford Grey from the 1929 film The Love Parade.

‘Spring Is Here’ (Ch.1; page 8)

Song from the 1929 show of the same title by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart. Not to be confused with a later song of the same name by the same writers, composed for their 1938 musical play “I Married an Angel”—far more commonly performed and recorded.

‘Whose Baby Are You?’ (Ch.1; page 8)

Song from the 1920 show The Night Boat by Jerome Kern and Anne Caldwell. It is curious that, even when he plays a Kern song, Bertie doesn’t choose one with Wodehouse lyrics here. Obviously a bit of Wodehouse modesty!

‘I Want an Automobile With a Horn That Goes Toot-Toot’ (Ch.1; page 8)

Unidentified so far. There are many songs from the period about automobiles, of course.

Berkeley Mansions, W.1. (Ch.1; page 8)

The W.1. postal district of London (now divided into W1A through W1W) is the highly desirable West End consisting of areas such as Mayfair, Marylebone, Piccadilly, Grosvenor Square and Soho. Only the UK book edition has W.1.; the magazine serials and the US first edition have simply Berkeley Mansions, W. [NM]

the Honourable Mrs. Tinkler-Moulke (Ch.1; page 8)

‘Honourable’ in this case is a courtesy title indicating that Mrs. Tinkler-Moulke is the daughter of a peer below the rank of Earl. In theory, she could also be a High Court judge, a government minister (not being a Privy Councillor), or Lord Provost of Glasgow, but in the 1930s there were few, if any, women in these positions.

Notice how Wodehouse creates comic effect by having Bertie use in informal speech a title that would normally only be used in the written form (e.g. for addressing an envelope). It immediately makes Mrs T-M seem pompous and self-important.

Lieutenant-Colonel J. J. Bustard, D.S.O. (Ch.1; page 8)

The bustard (otis tarda) is the largest European bird, extinct in the British Isles since the 1830s, despite recent attempts to reintroduce it on Salisbury Plain. Bustard occurs occasionally as a real English surname, but Wodehouse presumably chose it for its associations with turkey-like pomposity (cf ‘bluster’ as well).

In “The Ordeal of Osbert Mulliner,” Sir Masterman Petherick-Soames claims to have horsewhipped Rupert Blenkinsop-Bustard on the steps of his club, the Junior Bird-Fanciers.

One might suppose that there is an allusion to the character Col. Mustard in the board game “Cluedo” (“Clue” in the US – trademark of Hasbro in both cases), but this game only appeared for the first time in 1947, having been invented by Anthony Pratt in 1943.

The D.S.O. (Distinguished Service Order) is a military decoration first awarded in 1886. Once again, Bertie makes the colonel ridiculous by being over-specific for the context.

Sir Everard and Lady Blennerhassett (Ch.1; page 8)

This was originally an English name, possibly Cumbrian, although all modern Blennerhassetts claim descent from the Anglo-Irish landowner Robert Blennerhassett, who settled at Blennerville in County Kerry in the late 16th century.

Sir Marmaduke Blennerhassett (1902–1940), 6th baronet, who was killed in action in the second world war, had an even better name than his fictional counterpart, although Wodehouse is more likely to have come across his father, Sir Arthur (1871–?). It is unusual for Wodehouse to use a real title in this way – possibly it was an accident. There is no evidence that he knew the Blennerhassetts.

Blennerhassett Island in West Virginia takes its name from Harman Blennerhassett (1765–1831), who was involved in the Burr conspiracy.

https://humphrysfamilytree.com/Blennerhassett/4th.baronet.html

[Mabel Murgatroyd’s father in the American magazine version of “Bingo Bans the Bomb” (Playboy, January 1965) is titled Lord Blennerhassett. —NM]

Mr. Manglehoffer (Ch.1; page 8)

This seems to be an invented name, although it sounds like a plausible anglicisation of a German or Jewish name: “Mangel” from German Mangold, a type of beet (or, less probably, from Mangel, want, shortage); and “-hofer” (originally Hofherr, i.e. proprietor, farmer), which is a common suffix in southern Germany and Austria.

A cottage ... if possible, honeysuckle-covered (Ch.1; page 8 or 9)

A cliché of romantic fiction, important in Wodehouse’s 1925 short story “Honeysuckle Cottage.” [NM]

Gospodinoff … Ripley (Ch.1; page 9)

Robert Leroy Ripley (1890–1949) started out as a newspaper cartoonist and baseball player. He came up with the “Believe it or Not” idea when working for the New York Globe, later moving to the Hearst group and expanding the newspaper cartoon into books, exhibitions (“Odditoriums”) and, most famously, a radio show.

The development of “Believe It or Not” from a newspaper space-filler to a huge industry is often cited by outsiders as the ultimate expression of the American obsession with the trivial, but Wodehouse was clearly a fan, and often uses Ripleyesque items in his writing, especially the “Our man in America” pieces for Punch.

I haven’t found any confirmation of the “Gospodinoff” item. Bagpipes (gaida) are prominent in traditional Bulgarian music. [Online newspaper archives show that Gospodinoff was featured in the May 6, 1930 “Believe It or Not” panel and explained more fully in the May 7 “Yesterday’s Explanations” footnotes. The day-long dance was “many years ago” in the Old World; Gospodinoff was living in Greenwich, Connecticut in 1930. Real-estate transaction notices in Connecticut papers show an Elia G. Gospodinoff as recently as 2012, so the family seems to have settled in for good. —NM]

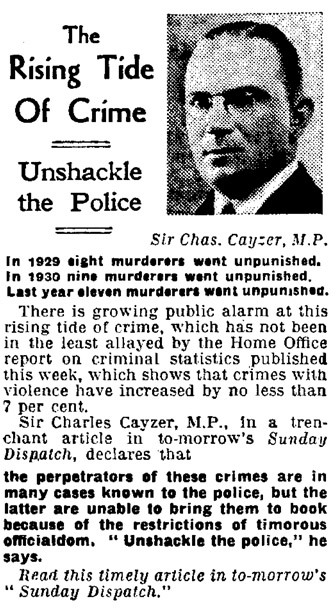

Mussolini (Ch.1; page 10)

Benito Mussolini (1883–1945) became Prime Minister of Italy in October 1922. He rapidly did away with the democratic process and concentrated power in his own hands, but people in Britain and America generally paid more attention to his economic success than to his human rights abuses until 1935, when his invasion of Ethiopia led to strong international condemnation (but no action). Writing in 1934, Wodehouse is simply using him as a symbol of authoritarianism.

Do I mean truckling? (Ch.1; page 10)

Yes, he does.

A truckle-bed is a low bed on castors that can be rolled under another bed when not in use. The verb “truckle,” which originally simply meant to sleep on such a bed, had taken on a figurative sense of “lying down unworthily” or “cowering” by the late seventeenth century.

Battle of Crécy (Ch.1; page 10)

At Crécy, in northern France, on 26 August 1346, Edward III of England defeated Philip VI of France in the early stages of the Hundred Years War. This victory made the English capture of Calais in the following year possible.

[Only the US magazine serial in Cosmopolitan includes the accent as in the French name; Strand magazine and both US and UK first editions simply read “Crecy” here. —NM]

Chapter 2

Chuffy

Runs from pp. 11 to 17 in the 1999 Penguin edition

the lemon-coloured (Ch.2; page 11)

Lemon-coloured gloves were the mark of a dandy; the poet Browning in his twenties was described as “slim and dark, and very handsome, and . . . just a trifle of a dandy, addicted to lemon-coloured kid gloves and such things.” [NM]

chilled steel (Ch.2; page 11)

I wonder if I have ever told you about Chuffy? (Ch.2; page 11)

No, this is the first mention of him in the Wooster saga. He reappears in Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves (1963) and is mentioned in the book versions of “Jeeves and the Greasy Bird” (Plum Pie and The World of Jeeves). [NM]

private school, Eton and Oxford (Ch.2; page 11) °

In this context “private school” means what in England and Wales is now usually called a “preparatory school,” i.e. a school that prepares young children to take the public school entrance examinations, usually when they are about 13 years old. Such schools are commonly run as commercial ventures; often the headmaster is also the owner and proprietor. Elsewhere, we are told that Bertie’s early education was at Malvern House, under the Rev. Aubrey Upjohn.

“Public school” in England and Wales (but not in Scotland or North America) refers to a small group of independent schools, usually having their origins in medieval charitable foundations, decently obscure for centuries, which in Victorian times took on the role of defining Britain’s future ruling élite. These were organized similarly to nonprofit corporations, with boards of trustees or governors, endowments, and no owner or stockholders. To be sent there you merely had to have wealthy parents; once you had been there, you were a gentleman. Eton College, on the Thames near Windsor, is the oldest public school in England. It was founded in 1440 by King Henry VI as ‘The King’s College of Our Lady of Eton beside Windsor.’

Oxford University was in existence by the twelfth century. Bertie’s college, which is elsewhere said to be Magdalen, was founded in 1448 by William of Wayneflete.

Chuffnell Regis … Somersetshire (Ch.2; page 11)

The Somersetshire coast extends along the southern shore of the Bristol Channel from Bristol to Exmoor. There are several well-known seaside resorts, including Weston-Super-Mare, Burnham-on-Sea, Watchet and Minehead.

The only seaside resorts in Britain with the suffix “Regis” (King’s) are Bognor, in Sussex, and Lyme, in Dorset.

in these times? He can’t even let it. (Ch.2; page 12)

The financial difficulties of many owners of large country estates were not new in the stock-market slump following 1929. As N.T.P. Murphy points out in A Wodehouse Handbook, in the early years of the twentieth century the death duties introduced by Lloyd George and rising taxation had already begun to affect many great families. Further taxes arising from the Great War made the situation worse. Murphy:

As a boy, Wodehouse had seen the heyday of the country houses but fully appreciated their later difficulties. As early as A Gentleman of Leisure (The Intrusion of Jimmy) [1910] he writes of noble establishments that have fallen on hard times. John Carroll of Money for Nothing [1928] works hard to keep the estate going…

Some great houses were let (leased) to institutions such as schools and sanitariums when no one could be found wealthy enough to maintain them as private residences, but as Chuffy notes (ch. 3, p. 25) the cost of renovations to make the entire house habitable would be enormous after decades of deferred maintenance. [NM]

the local doctor and parson (Ch.2; page 12)

As educated men, these professionals would be admitted to County society and could socialize with their wealthier neighbors. [NM]

Seabury (Ch.2; page 12)

An unusual name for a British boy – Samuel Seabury (1729–1796), the first American bishop in the Episcopal Church, has lent his name to many institutions in the USA, but is essentially unknown in Britain.

Dower House (Ch.2; page 12)

A house, usually in the grounds of a larger house, but at a safe distance from it, intended as a residence for the widow (dowager) of the former head of the family.

one of the lads (Ch.2; page 12)

A shortening of “one of the lads of the village”; an ironic term for the bright young idle men-about-town of which Bertie is such a good representative. [NM]

“The moment I saw you, I said, ‘Here comes one of the lads of the village.’ This is no time for delay. If we are to liven up this great city, we must get to work at once.”

The Prince and Betty (UK edition), ch. 4 (1912)

He was All Right, a sportsman, one of the lads, and a good egg.

Archie Moffam in “The Man Who Married An Hotel” (1920) [omitted from Indiscretions of Archie, 1921]

Never before had I encountered a curate so genuinely all to the mustard. Little as he might look like one of the lads of the village, he certainly appeared to be real tabasco, and I wished he had shown me this side of his character before.

“Aunt Agatha Takes the Count” (1922; as ch. 4 in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

One would have expected a New York playboy, widely publicized as one of the lads, to confine himself to prose, and dirty prose, at that.

Jeeves in the Offing/How Right You Are, Jeeves, ch. 3 (1960)

Norman Murphy, in The Reminiscences of the Hon. Galahad Threepwood, explains “one of the lads” as the shortened form of the phrase, and that “from about 1870 till 1914, ‘the village’ was the term used for that area of London stretching from St Paul’s in the east to Hyde Park Corner in the west. ‘The lads of the village’ was the name given to fellows like myself [Galahad] who spent our days and nights making use of the facilities for harmless, and not so harmless, entertainment to be found there.”

more or less of a washout (Ch.2; page 12)

Carlton (Ch.2; page 12)

The Carlton Hotel was opened by Ritz and Escoffier in 1899. See also A Damsel in Distress.

on the edge of the harbour … not a neighbour within a mile (Ch.2; page 13)

On the face of it, this sounds unlikely. In most places with a harbour, the harbour will have been the focus of economic activity, so one expects the village to be clustered around it.

If we take the mile as an exaggeration, one place that might fit could be Minehead, where the town is stretched out along a sandy bay, but the harbour is tucked in under the cliffs at the far end, leaving little room for building.

Like Chuffnell Regis, Minehead was also the property of a single family – the Luttrells – and although quite small, it would have had enough holiday visitors to support a summer theatre.

https://www.mineheadonline.co.uk/history.htm

Police Sergeant Voules (Ch.2; page 14)

The best-known Voules in the canon is of course the man behind the wheel of the Blandings Hispano-Suiza. Reggie Pepper’s valet and the stand-in clergyman in The Small Bachelor are among the others.

Stirling Voules (1843–1923), who came from Somersetshire, played cricket for Oxford University in the 1860s, but seems to have retired from first-class cricket well before Wodehouse’s time.

Daniel H. Garrison: Who’s Who in Wodehouse (1991)

nigger minstrels (Ch.2; page 14)

Note: the word “nigger” is nowadays considered offensive by many people. It has consequently been deleted or replaced in some recent US editions. In the thirties, this was the usual word for this kind of entertainment, and it would not have occurred to Wodehouse that it would offend some of his readers.

[As far as I am aware, the only times this word is used pejoratively in Wodehouse to refer to people of African descent are when it is being spoken by American characters who are shown up by Wodehouse as being racially prejudiced. In other words, he uses it realistically, as Mark Twain did. In the mouths of sympathetic characters like Bertie, or in Wodehouse’s narrative voice, the word seems always to refer to white minstrel performers in blackface, and is used without any appearance of animosity. Black characters are generally called something else, for instance “the coloured chappie in charge of the elevator” in “Jeeves and the Chump Cyril.” See also the first Kid Brady story for an early look at how the young Wodehouse reacted to American racial prejudice. —NM]

Minstrel shows first appeared in the USA in 1830, and the vogue had reached Britain by the 1840s. They involved white musicians made up as caricatures of black people from the South of the USA, performing songs and ritualised jokes in an exaggerated dialect. The songs of Stephen Foster (1826–1864) soon took over as the core of the repertoire.

The format persisted in Britain for a long time – it was only in 1978 that the BBC finally acknowledged the racist implications of the “Black and White Minstrel Show.” However, by the 1930s minstrel shows were no longer the dominant form of seaside entertainment.

parted brass-rags (Ch.2; page 14)

Naval expression: ratings used to share a bag of polishing rags with a colleague (a “raggie”), so parting brass rags was a consequence of separating after a disagreement. See Very Good, Jeeves.

high road … low road (Ch.2; page 14)

O ye’ll tak’ the high road, and I’ll tak’ the low road,

And I’ll be in Scotland afore ye,

But me and my true love will never meet again,

On the bonnie, bonnie banks o’ Loch Lomon’.

Anonymous: Loch Lomond (traditional Scottish song)

immortal rind (Ch.2; page 14)

Rind here is a jocular synonym for the colloquial usage of “crust” meaning impudence or “cheek.” The OED cites George Ade in a 1901 newspaper column: “Do you have the immortal Rind to say that a galvanized Bun and one little Oasis of Ham are worth ten cents?” Wodehouse picked up on this and used “immortal rind” as early as 1915 in Something Fresh/Something New. [NM]

accepted his portfolio (Ch.2; page 14)

The word portfolio is often used figuratively to describe the tasks of a government minister (this was originally a French usage). Thus, when a minister resigns she is said to hand in her portfolio. For an valet to do this is delightfully incongruous.

bite the bullet (Ch.2; page 14)

Said to come from the practice of giving wounded soldiers a bullet to bite on while surgery was performed.

‘I shall watch your future career with considerable interest.’ (Ch.2; page 14?)

See A Damsel in Distress.

follow the green line (Ch.2; page 15)

This injunction, from the idea of painting a green line on the floor, wall or pavement to guide people to a particular destination, must already have been a cliché by the early 1920s – the Art Steel Company in the Bronx were using it as an advertising slogan for their green-painted filing cabinets, and the Scott Fitzgerald example below has the air of referring to something that would have been well-known to readers. I haven’t been able to identify the origin of the practice, but it seems to be more an American than a British idea.

The Townsends had determined to assure their party of success, so a great

quantity of liquor had been surreptitiously brought over from their house

and was now flowing freely. A green ribbon ran along the wall completely

round the ballroom, with pointing arrows alongside and signs which instructed

the uninitiated to “Follow the green line!” The green line led

down to the bar, where waited pure punch and wicked punch and plain dark-green

bottles.

F. Scott Fitzgerald: “The Camel’s Back” (Saturday Evening Post, 21 February 1920)

https://www.sc.edu/fitzgerald/pair of pustules (Ch.2; page 15?)

See Hot Water.

giving me the pip (Ch.2; page 16?)

soup and fish (Ch.2; page 16)

Gentlemen’s formal evening dress.

when my toilet was completed (Ch.2; page 16)

In other words, “when I had finished dressing.” The word toilet originally referred to a light cloth used to protect clothes (as during hairdressing) or to cover a dressing-table, then to the table itself and the articles found there (comb, brush, etc.), then to the act of dressing and grooming, or the clothing or hairstyle itself (often toilette); later to a dressing room, sometimes having washing facilities. Its use as a euphemism for lavatory or water-closet began in America in the late nineteenth century but was rare in Britain until the mid-twentieth century. [NM]

meet at Philippi (Ch.2; page 17)

Brutus: There is a tide in the affairs of men,

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune;

Omitted, all the voyage of their life

Is bound in shallows and in miseries.

On such a full sea are we now afloat;

And we must take the current when it serves,

Or lose our ventures.

Cassius: Then, with your will, go on;

We’ll along ourselves, and meet them at Philippi.

Shakespeare: Julius Caesar IV:3, 249–257

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for more references to this passage.

July the fifteenth (Ch.2; page 17)

For reference in later discussions of time of day, assuming the location of Minehead as above, dawn on 15 July would be at 04:33 British Summer Time, sunrise at 05:17, sunset at 21:22, dusk ending at 22:06. [NM]

a meditative cigarette (Ch.2; page 17)

A classic transferred epithet: see Right Ho, Jeeves. [NM]

Chapter 3

Re-enter the Dead Past

Runs from pp. 18 to 26 in the 1999 Penguin edition.

Chapter title: the Dead Past (Ch.3; page 18)

Tell me not, in mournful numbers,

Life is but an empty dream!

For the soul is dead that slumbers,

And things are not what they seem.

Life is real! Life is earnest!

And the grave is not its goal;

Dust thou art, to dust returnest,

Was not spoken of the soul.

Not enjoyment, and not sorrow,

Is our destined end or way;

But to act, that each tomorrow

Find us farther than today.

Art is long, and Time is fleeting,

And our hearts, though stout and brave,

Still, like muffled drums, are beating

Funeral marches to the grave.

In the world’s broad field of battle,

In the bivouac of Life,

Be not like dumb, driven cattle!

Be a hero in the strife!

Trust no Future, howe’er pleasant!

Let the dead Past bury its dead!

Act,—act in the living Present!

Heart within, and God o’erhead!

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time;—

Footprints, that perhaps another,

Sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, shall take heart again.

Let us then be up and doing,

With a heart for any fate;

Still achieving, still pursuing,

Learn to labor and to wait.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882): A Psalm of life

wheeze (Ch.3; page 18)

Here used as a synonym for “scheme”; more often used as a catchphrase or repeated joke; see Right Ho, Jeeves. [NM]

cloth-headed (Ch.3; page 18)

See Money in the Bank.

frowsty (Ch.3; page 18)

Stuffy, underventilated, smelly. [NM]

a hundred quid (Ch.3; page 18?)

One hundred pounds sterling. The Bank of England inflation calculator suggests a factor of roughly 73 from 1933 to 2020, so in modern terms this would be about £7,300 or US$10,000. [NM]

whacking great yacht (Ch.3; page 19?)

See If I Were You.

gasper (Ch.3; page 19?)

a cheap cigarette [NM]

No, I’m wrong. (Ch.3; page 19?)

Thus in UK first edition; in Strand, Cosmopolitan, and US first edition, this reads “No, I’m a liar.” We must assume an editorial intervention at Herbert Jenkins Ltd.

the old two-seater (Ch.3; page 19?)

We learn in Chapter 8 that this is a Widgeon Seven.

fiend in human shape (Ch.3; page 19?)

See The Mating Season.

“Hallo” (Ch.3; page 19?)

The UK first edition uses the spelling “Hallo” most often; the US and UK magazine serials and the US book spell it “Hullo” throughout. [NM]

aeroplane ears (Ch.3; page 20?)

In Quick Service (1940), Mr. Steptoe is described at one point as having aeroplane ears, and elsewhere “ears like the handles of an old Greek vase” and “ears that seemed to be set at right angles to his singularly unprepossessing face”; we thus have a definition of the term used here. [NM]

Rogues’ Gallery (Ch.3; page 20)

The name normally used for the police collection of photographs of known criminals.

Young Thos. (Ch.3; page 20)

Aunt Agatha’s dreadful son appeared in “Jeeves and the Impending Doom” (1926) being tutored by Bingo Little, and again in “Jeeves and the Love that Purifies” (1929). Later reappears in The Mating Season.

“Thos.” was a conventional abbreviation for Thomas, seen frequently over the doors of shops, etc., but incongruous in spoken language. His family name is presumably Gregson, the name of Aunt Agatha’s first husband.

Mr. Blumenfield’s Junior (Ch.3; page 20)

See “Jeeves and the Chump Cyril” in The Inimitable Jeeves and “Jeeves and the Dog McIntosh” in Very Good, Jeeves.

[If the Penguin edition has “Blumenfield” here, it is unique; all other editions of Thank You, Jeeves including original magazine serials spell the name “Blumenfeld.” See The Inimitable Jeeves. —NM]

Sebastian Moon (Ch.3; page 20)

See “Jeeves and the Love that Purifies” in Very Good, Jeeves.

Bonzo (Ch.3; page 20)

Also appears in “Jeeves and the Love that Purifies” in Very Good, Jeeves.

… and the field (Ch.3; page 20)

An echo of racing reports, referring to the “also-ran” horses after the individually-named winners.

nif (Ch.3; page 21)

Smell – slang, esp. among schoolboys. The OED cites this as one of the first uses in print. It may possibly be derived from sniff. [Spelled “niff” in the Strand and Cosmopolitan serials and in the US book. —NM]

five shillings (Ch.3; page 21)

25p in modern coin; one-quarter of a pound sterling. A largish sum for a schoolboy in those days, with the buying power of about £18 today.

bronzed and fit (Ch.3; page 22?)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

The scales fell from my eyes. (Ch.3; page 22?)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

…something Lady Chuffnell had picked up en route (Ch.3; page 23)

As she is Lady Chuffnell, the marriage resulting in Seabury must have been prior to her marriage to the late Lord C. Seabury presumably can’t be more than 12 or so, which suggests that her marriage to Lord C must have been rather brief.

pegged out (Ch.3; page 23?)

Slang for “died”; cited from the 1850s from US sources in the OED. Though existing citations for connections to games are not as old as that, there may be a connection to croquet, in which hitting the winning peg with one’s ball is the final stroke in the game, or to cribbage, in which advancing one’s scoring peg to the last hole of the board is one way of winning the game before the show of hands. [NM]

relict (Ch.3; page 23?)

Survivor, widow; a historical term now mostly in formal or mock-formal use. The OED cites Wodehouse’s use in The Small Bachelor, ch. 2 (1927). [NM]

it’ll be in the Morning Post in a day or two (Ch.3; page 24)

See Right Ho, Jeeves. [NM]

…getting Aunt Myrtle off this season (Ch.3; page 24)

This is an echo of the language usually associated with the parents of debutantes. The ‘season’ was the period of the year when aristocratic families moved into their London houses and took their daughters to a series of balls to meet eligible young men. By the thirties, all but the wealthiest had been forced to sell off their London mansions, but the idea of a London season persisted until the fifties.

widower more than two years (Ch.3; page 24)

The first Lady Glossop, née Blatherwick, is mentioned as a friend of Bertie’s Aunt Agatha in “Scoring Off Jeeves” (1922; as ch. 5 in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923) and as a sister of Professor Pringle’s wife in “Without the Option” (1925; in Carry On, Jeeves!). [NM]

Our Humble Heroines (Ch.3; page 24)

??? This sounds as though it might be the title of a patriotic film or a wartime poster, but I haven’t been able to trace it yet.

[Maurice Maeterlinck, in The Life of the Ant (1930), refers to the fertile females: “our humble heroines find it easier than we do to modify, in case of need, their fundamental laws, or even to reverse them, adapting themselves to circumstances, and turning these to account.”

[An article in the Pittsburgh Press, July 13, 1933, about the lack of realism in hair and makeup of Hollywood actresses, says that “even in such ‘homey’ pictures as ‘Peg O’ My Heart’ and ‘State Fair,’ our humble heroines are on every beauty parlor secret.” —NM]

fifteen thousand quid (Ch.3; page 25)

Roughly equivalent in buying power to £1.1 million today. [NM]

get outside (Ch.3; page 25)

Wodehouse didn’t invent this humorous inversion of putting food or drink inside oneself, but he certainly helped to popularize it, beginning in 1906; see the endnote to “How Kid Brady Joined the Press” on this phrase. [NM]

Dwight (Ch.3; page 25)

Nowadays we associate this name mostly with Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890–1969), Second World War general and later President of the USA. However, in 1934 he was an obscure professional soldier unknown outside military circles.

The name owes its original popularity in the USA to the Baptist minister Timothy Dwight (b. 1752), who was president of Yale University in the late 18th century. Was Wodehouse perhaps reading about American church history when he wrote Thank You, Jeeves?

[Ian Michaud notes: in Piccadilly Jim an assortment of Rollos, Clarences, Dwights and Twombleys were frisking around Ann on the boat crossing the Atlantic and later we discover that Willie Partridge’s father was the famous inventor Dwight Partridge. There was an artist called Robert Dwight Penway in The Coming of Bill. And a few years before Thank You, Jeeves, in Big Money a different Ann told Twombley Burwash (“You know. The Dwight N. Burwashes”) that she would only consider marrying him if he hit a policeman, a task Twombley declined to take on.]

Other American Dwights include Dwight Blenkiron of Chicago (Sam the Sudden, 1925), Dwight Stoker in Thank You, Jeeves (1934), Dwight Z. Rollitt in the US version of “Ordeal by Golf” (1919), and perhaps Dwight Messmore in “Up from the Depths” (1950), in which the Fourth of July is mentioned.

Chapter 4

Annoying Predicament of Pauline Stoker

Runs from pp. 27 to 36 in the 1999 Penguin edition.

The chapter heading sounds as though it might be an indirect reference to the famous 1914 silent film serial The Perils of Pauline, in which Pearl White was forever being tied to railway tracks.a-twitter (Ch.4; page 27)

A shortened form of “all of a twitter”; see The Inimitable Jeeves.

as juicy a biff (Ch.4; page 27)

as intense a blow [NM]

removed the lid (Ch.4; page 27)

In the days when gentlemen wore hats, it was considered polite to take one’s hat off when greeting someone. The gesture is said to be a survival of knights wearing helmets; more likely it is just a way of giving the other party a clear look at your face so that they can decide for themselves that you look harmless.

under the ether (Ch.4; page 27)

anaesthetised

Colonel Wooster (Ch.4; page 27)

David Wooster (1711–1777), a Connecticut man, served in the British army against the French and the native Americans. In 1775, he resigned his commission as colonel of a Connecticut militia regiment to become a general in the revolutionary army of the American colonists. He was mortally wounded in action in the Quebec campaign.

Masters of Hounds (Ch.4; page 28)

The Master of [Fox-]hounds (MFH) is the person in charge of a fox hunt. Masters traditionally have red faces, loud voices and short tempers, but, hunting being a dangerous activity, they presumably have to be competent organisers, good at ordering people around. The title “Master” is used equally for men and women, as Wodehouse implies.

scratch the entire fixture (Ch.4; page 29?)

Sporting terminology for “cancel the whole event.” [NM]

expression … of a stuffed frog (Ch.4; page 30?)

See Bill the Conqueror.

Soul’s Awakening (Ch.4; page 30)

A sentimental portrait by James Sant (1820–1916) of his young niece (or great niece) Annie Kathleen Rendle, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1888 and widely reproduced in engravings and prints. [NM]

A color engraving of the painting

An 1897 interview with the artist, with black-and-white engraving of the painting

[The 1922 Rudolf Steiner book of the same title previously mentioned here is probably not relevant, as Wodehouse was referring to the look of the portrait in stories as early as 1911. The other artwork previously noted here, “a sentimental mezzotint engraving by Charles John Tomkins (1847–1897), published by Graves in 1892,” is listed in a guide to artworks as a companion piece to The Soul’s Awakening. —NM]

copped it (Ch.4; page 30)

See Very Good, Jeeves.

You find the girl, and he does the rest. (Ch.4; page 30)

A takeoff on the longtime Kodak advertising slogan “You press the button, we do the rest”— famous in Britain as well as America since 1890 at least. [NM]

Janet Gaynor (Ch.4; page 31)

(Laura Gainor, 1906–1984) Film actress. Made her debut in The Johnstown Flood (1926), and was one of the few silent actors to do well in talkies. Her biggest success was the 1937 version of A Star Is Born. She was described as “a waif with large innocent eyes.”

A 1931 publicity photo of Janet Gaynor

“…do you keep cats in your bedroom?” (Ch.4; page 32?)

The incident is recounted in “Sir Roderick Comes to Lunch” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923). [NM]

mot juste (Ch.4; page 34?)

French for the “exact word” that expresses the intended meaning. Wodehouse often attributes this goal, correctly, to novelist Gustave Flaubert (1821–1880, best known for Madame Bovary), who argued that careful choice of the right word was the key to literary realism and an essential truth in writing. [NM]

Marmaduke (Ch.4; page 34?)

A masculine name, derived from Irish Gaelic, with comical upper-class English overtones according to thinkbabynames.com. [NM]

Like “Murgatroyd” in the preface, Marmaduke is a name found in Gilbert and Sullivan. The elderly baronet (but, somewhat surprisingly, not a “bad baronet”) Sir Marmaduke Pointdextre is the tenor’s father in The Sorcerer. [IM]

how the other half of the world lives (Ch.4; page 34?)

The phrase can be traced back to the title of a 1752 satirical book, Low-life: Or One Half of the World Knows Not how the Other Half Lives...— one of those interminable eighteenth-century titles that fill the title page. The authorship is variously attributed to William Hogarth and to Thomas Legg. Another citation from the same decade: Matthew Henry’s commentary on the Book of Job, chapter 30 (1758).

The phrase became popular again in 1890 with the publication of How the Other Half Lives, a pioneering work of photojournalism by Jacob Riis documenting conditions in New York tenements. [NM]

tidings of great joy (Ch.4; page 35?)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

king in Babylon ... Christian slave (Ch.4; page 35)

Or ever the knightly years were gone

With the old world to the grave,

I was a King in Babylon

And you were a Christian Slave.

I saw, I took, I cast you by,

I bent and broke your pride.

You loved me well, or I heard them lie,

But your longing was denied.

Surely I knew that by and by

You cursed your gods and died.

And a myriad suns have set and shone

Since then upon the grave

Decreed by the King of Babylon,

To her that had been his Slave.

The pride I trampled is now my scathe,

For it tramples me again.

The old resentment lasts like death,

For you love, yet you refrain.

I break my heart on your hard unfaith,

And I break my heart in vain.

Yet not for an hour do I wish undone

The deed beyond the grave,

When I was a King in Babylon

And you were a Virgin Slave.

William Ernest Henley (1849–1903): To W. A.

charging into a railway restaurant for a bowl of soup (Ch.4; page 36)

This image dates back to Wodehouse’s younger days – the advent of corridor trains and restaurant cars on most routes around 1900 put an end to the old practice of meal stops on long railway journeys.

[The modern equivalent is found on long-distance bus journeys when the driver pulls in to a highway truck-stop to give the passengers a short meal-break. —IM]

Chapter 5

Bertie Takes Things in Hand

Runs from pp. 37 to 44 in the 1999 Penguin edition

whereabouts ... at the wash (Ch.5; page 37)

Wodehouse had Lord Marshmoreton laughing over this gag from a newspaper in Chapter VI of A Damsel in Distress. [NM]

a sentiment deeper and warmer than that of ordinary friendship (Ch.5; page 38?)

Wodehouse uses this phrase often enough that I had always taken it to be a stock phrase of Victorian proposals, but there is little available evidence for the phrase in full before him. In Horatio Alger’s A Fancy of Hers (1892), one man writes to his friend about a young woman he is interested in: “If I am not too precipitate, I hope that esteem may pave the way for a deeper and warmer sentiment.” A platonic friendship between German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher and Henrietta Herz was described by her (quoted in a review published in 1860): “There were…people who, knowing the intimacy that existed between us, suspected that it was based upon a warmer sentiment than friendship. They were mistaken.” And this is as close as I can find until “The Truth About George” (1926), “Jeeves and the Spot of Art” (1929), this novel, and “Dumb Chums at Riverhead,” one of his Punch columns (Sept. 7, 1955) about a breeding pair of armadillos. In Right Ho, Jeeves, Bertie uses the similar phrase “sentiment warmer and stronger than that of ordinary friendship.” In Cocktail Time, ch. 17, Wodehouse’s narration uses “feelings deeper and warmer than those of ordinary friendship” to describe Phoebe Wisdom’s attraction to her butler Peasemarch. [NM]

dippy about the man (Ch.5; page 39?)

The OED has a 1903 citation for “dippy” alone meaning crazy, and, when used with “about” or “over” defines it as “in love with.” A 1904 citation from George Ade (“to get dippy over the Honest Working-Girl”) and a 1923 one from Wodehouse (“You’ve no notion how dippy I am about him.”) illustrate the “in love” sense. Actually, in one serial episode of The Adventures of Sally Gladys Winch uses “dippy” twice to indicate that Fillmore Nicholas is crazy to star her in a revue, as well as once, as quoted above, to indicate that she loves him anyway. [NM]

a worm i’ the bud (Ch.5; page 39)

She never told her love,

But let concealment, like a worm i’ th’ bud,

Feed on her damask cheek.

Shakespeare: Twelfth Night II:iv, 110

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for more references to this passage.

[In Hot Water (1932) we learn that Blair Eggleston is the author of the novel Worm i’ the Root. —IM]

Missing on every cylinder. (Ch.5; page 39)

An automobile engine will run roughly if it is missing on even one cylinder — that is, if due to such causes as a dirty spark plug, failed ignition wiring, or bad valve operation, one cylinder doesn’t explode its fuel mixture at the proper time to contribute its share of the driving force. An engine missing on every cylinder will of course not run at all, so this is a metaphor for Chuffy’s total failure to act on his feelings for Miss Stoker. [NM]

love laughs at … locksmiths (Ch.5; page 39)

This expression seems to be proverbial. It has been used as the title of several plays and operas, most notably by George Colman the Younger (1762–1836).

fifty million dollars (Ch.5; page 39)

Using US consumer price index data from 1934 to mid-2021, the relative inflated worth would be just over a billion dollars in modern terms. [NM]

kicked the bucket (Ch.5; page 39)

This colloquial euphemism for dying was recorded in a 1785 slang dictionary; an 1888 dictionary explains it as referring to a different sense of the word “bucket” than the container for water. In Norfolk, the beam on which a butcher suspends a slaughtered pig upside-down was called a “bucket”; since the pig’s back feet were near the beam, the dead pig was said to kick the bucket. [NM]

Benstead (Ch.5; page 39)

Benstead/Binstead was a favourite Wodehouse name, obviously inspired by Arthur “the Pitcher” Binstead (1846–1915), founder and chronicler of the Pelican Club.

Kid Lazarus, the man without a bean (Ch.5; page 39 or 40)

Not the Lazarus of Bethany, raised from the dead in chapter 11 of the Gospel of John, but rather the poor man Lazarus of Luke 16:19–31, who longed to eat the crumbs that fell from the table of a rich man. [NM]

plenty of bust blokes have married oofy girls (Ch.5; page 40?)

“Oof” was late-Victorian slang for money, so “oofy” means wealthy. [NM]

put the bite on (Ch.5; page 41?)

Like bite the ear, this is slang for asking for a loan. [NM]

complex (Ch.5; page 42?)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

musical comedy … Lord Wotwotleigh (Ch.5; page 42)

Seems to be invented. [The name is a takeoff on the upper-class English stock phrase “What? What?”; see note for page 204? below. —NM]

continue to do business at the old stand (Ch.5; page 43)

This phrase often appears in advertisements from around the turn of the century when a business has been taken over by a new owner. It seems to be more American than British.

See also Bill the Conqueror.

…you really are sure it is ‘damask’? (Ch.5; page 43)

The word “damask” has been used in English to describe many disparate items associated with the city of Damascus. In modern use, it normally refers to textiles, especially the twilled white linen used for tablecloths and the like, hence Bertie’s bewilderment.

Shakespeare was using it to describe the colour of the damask rose. Apparently there is some doubt as to precisely which varieties of rose were covered by this name, but everyone agrees that they were red.

[Wodehouse has one of his characters misquote this to great effect. Colonel Wedge, in chapter 6 of Full Moon, is worried that his daughter Veronica is brooding because Tipton Plimsoll is diffident about proposing to her. He quotes the Shakespeare passage as “let concealment, like a worm i’ the bud, feed on her damned cheek.” As a bluff military man, the phrase “damned cheek” (meaning roughly “blasted impertinence”) would come to mind more easily than the archaic “damask”. —NM]

I have got the whole thing taped out. (Ch.5; page 43–44?)

Measured, assessed, planned fully. The OED cites a similar passage in Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 9, in which Bertie asks Jeeves: “Didn’t I tell you I had everything taped out?” [NM]

till I see the whites of his eyes (Ch.5; page 43–44?)

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

half-bot of the best (Ch.5; page 44)

Half-bottle (of wine).

Chapter 6

Complications Set In

Runs from pp. 45 to 63 in the 1999 Penguin edition

Master Dwight … Master Seabury (Ch.6; page 45)

‘Master’ was the title used when it was necessary to address a young boy formally. Jeeves would naturally use this form, to indicate their status as guests of his employer.

trillions (Ch.6; page 45?)

Traditionally, in British English, a billion was a million squared, or 1012, and a trillion was a million cubed, or 1018. Beginning gradually in the 1950s, and officially in UK statistics since 1974, British writers have conformed to the longtime usage of the USA and France, defining a billion as a thousand millions, 109, and a trillion as a thousand billions, 1012. But in 1933, a British boy like Master Seabury would have intended the larger or “long scale” definition of trillions. [NM]

imbroglio (Ch.6; page 46)

Confusion, entanglement, disagreement (a direct borrowing from Italian)

…the subject of socks (Ch.6; page 47)

Jeeves and Bertie have had a number of disputes on this delicate subject, notably in “Startling Dressiness of a Lift Attendant” (in The Inimitable Jeeves, the chapter which concludes the short story “Jeeves and the Chump Cyril”).

shining like twin stars (Ch.6; page 47)

See Money for Nothing.

“Sonny Boy” … Beefy Bingham’s Church Lads (Ch.6; page 47)

See “Jeeves and the Song of Songs” in Very Good, Jeeves. The Rev. Rupert “Beefy” Bingham is one of the handful of characters who link the world of Jeeves with that of Blandings – he later marries Lord Emsworth’s niece Gertrude and becomes vicar of Much Matchingham.

The Church Lads’ and Church Girls’ Brigade was founded in 1891 as an Anglican counterpart to the secular Boy Scout movement, and still exists. They appear in a number of stories, most notably in Service with a Smile, where Lord Emsworth sabotages their tents.

It was one of those things that want doing quickly or not at all (Ch.6; page 48?)

If it were done when ’tis done, then ’twere well

It were done quickly...

Shakespeare: Macbeth I:vii, 1–2 [NM]

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for more references to this passage.

Homburg (Ch.6; page 48)

A soft felt hat with a curled brim and a dented crown, named after the spa near Wiesbaden. Made popular by Edward VII as Prince of Wales in the 1890s.

floater (Ch.6; page 48?)

stout Cortez (Ch.6; page 49)

See p. 3 above.

in his kick (Ch.6; page 49)

In his pocket (19th century British slang). cf. Summer Moonshine Ch. 1: “She slung your brother Joe out.” “And with only ten dollars in his kick, mind you.”

hoofing his daughter’s kisser (Ch.6; page 49)

In Wodehouse hoof as a verb normally means either to go on foot, or to dance (on stage). Another occasional meaning is to throw out, or eject, someone. Here, Wodehouse seems to be using it to mean “kick.” Presumably he resorts to this because he has already used “kick” in a quite different sense a couple of sentences previously.

Bertie, as usual, is digging himself in too deep linguistically – “kisser” can mean either “mouth” or “person who kisses.” The sensible interpretation here is the latter, but on first reading the phrase we get a fleeting impression of Stoker trying to decide which of the two he can kick. Knowing Wodehouse, this ambiguity is deliberate.

a touch of the iron hand (Ch.6; page 50?)

Polite firmness; see Carry On, Jeeves for the full phrase that is probably being alluded to here.

the work of a moment (Ch.6; page 50?)

See A Damsel in Distress.

Follow the dictates of the old heart (Ch.6; page 50?)

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

port … the last of the ’85 (Ch.6; page 51)

Wine-growers in Europe were starting to recover from the devastation of phylloxera and mildew by the early 1880s; 1885 was one of the first years since 1845 when significant quantities of good quality wine could be produced.

Two bottles of 1885 port were sold recently (Oct. 2000) for $250 each.

Size nine-and-a-quarter (Ch.6; page 51)

British hat sizes are based on the diameter of the head in inches. The largest standard size is 7 3/4 (63 cm). Size 9 1/4 would be about 75 cm! (US sizes are slightly smaller than British ones, but look similar; if Bertie is using a US size, it would be about 73cm...).

something in me that strikes a chord… (Ch.6; page 51)

Compare: [NM]

“…it is a known scientific fact that there is a particular style of female that does seem strangely attracted to the sort of fellow I am.”

“Very true, sir.”

“I mean to say, I know perfectly well that I’ve got, roughly speaking, half the amount of brain a normal bloke ought to possess. And when a girl comes along who has about twice the regular allowance, she too often makes a bee line for me with the love light in her eyes. I don’t know how to account for it, but it is so.”

“It may be Nature’s provision for maintaining the balance of the species, sir.”

“Without the Option” (1925; in Carry On, Jeeves!)

demesne (Ch.6; page 51?)

Technically, in land law, the possession of real estate as one’s own. Bertie is using the more modern sense of the land so possessed: an estate, consisting of a mansion and its immediately surrounding grounds, park, farm, etc. Note also the figurative sense in Keats’s poem referenced above.

muffins (Ch.6; page 53)

These would of course be the English type, small, flat cakes made from bread dough and dried fruit, and eaten toasted with butter.

storm-tossed soul … harbour (Ch.6; page 53)

This may be a reference to an evangelical hymn – if so I haven’t been able to trace it yet. “Storm-tossed soul” is a cliché of religious language.

[A Google search for the phrases “storm-tossed soul” and “safely into harbour” together returns only online quotations of this sentence, so this combination appears to be a Wodehouse original. —NM]

coaching his college boat (Ch.6; page 56)

Oxford and Cambridge colleges have their own rowing clubs, which compete against each other within the university. When rowers are training, the coach generally cycles alongside, shouting abuse through a megaphone from the towpath.

put the lid on it (Ch.6; page 56?)

See Ukridge.

arnica (Ch.6; page 56?)

See Money for Nothing.

durance vile (Ch.6; page 57?)

immuring (Ch.6; page 57)

Imprisoning (literally: walling in)

You could see Reason returning to her throne (Ch.6; page 59?)

See Hot Water. Another such allusion is in chapter 9.

seven-and-six for the licence (Ch.6; page 59?)

Seven shillings and sixpence, three-eighths of a pound sterling. Roughly equivalent to £27 or $35 US in modern buying power. Coincidentally, the first UK edition of this book was priced at seven-and-six too. [NM]

the man behind the Prayer Book (Ch.6; page 59?)

That is, the clergyman who performs the wedding. In the Church of England, the text of the wedding service is included in the Book of Common Prayer. (In the US first edition, “prayer book” is in lower case; in the UK magazine serial, “prayer-book” is hyphenated in lower case; in the US magazine serial, this sentence is omitted.) [NM]

I had never heard such crust in my life (Ch.6; page 60?)

Colloquially, “crust” means “impudence”; see Something Fresh.

special licence (Ch.6; page 60)

This can mean two different things. In the Anglican church, a special licence may be granted by the Archbishop of Canterbury to allow a couple to marry in a church other than that of the parish where one of them lives.

What Bertie is referring to is almost certainly a special licence from the Registrar, which allows a civil marriage to take place with only one day’s notice, instead of the usual three weeks.

Boat Race … Eustace H. Plimsoll (Ch.6; page 61) °

The Oxford and Cambridge boat race takes place on a four and a half mile course on the Thames (between Mortlake and Putney), on a Saturday during the Easter vacation. It was first held in 1829.

Eustace H. Plimsoll seems to be the first appearance of the name Plimsoll in the canon: Veronica Wedge’s fiancé, Tipton Plimsoll, first appears in Full Moon (1947).

Bertie seems to have come to grief on Boat Race night a number of times in his career; see The Code of the Woosters.

Alleyn Road exists: it is just round the corner from Acacia Grove, which Norman Murphy [In Search of Blandings] identifies as the setting for most of the Valley Fields novels. It is named for the Elizabethan-era actor Edward Alleyn, founder of Plum’s alma mater Dulwich College. It is curious that on this occasion Bertie chose the middle-class West Dulwich rather than the more obscure East Dulwich normally used for false addresses by the likes of Lord Ickenham (Uncle Dynamite); see Very Good, Jeeves for more.

a solitary steak and fried (Ch.6; page 62?)

Fried potatoes, of course. UK editions from the original 1934 plates have the misprint “friend” here (p. 89). A similar error, “friend potatoes,” was made in the first UK edition of Indiscretions of Archie (1921). [NM]

…measuring me for my lamp-post (Ch.6; page 62)

Dickens introduced English readers to the Parisian practice of hanging people from streetlamps in A Tale of Two Cities.

Number One touring towns (Ch.6; page 62?)

Provincial theaters were ranked by the potential revenue they could return to a touring theatrical company, and managers would cast different troupes of performers to match with different classes of theaters. The best actors would be in the Number One company which would visit the Number One towns, and so on down the line. [NM]

a gesture which had once impressed him very favorably when exhibited on the stage by the hero of the number two company of “The Price of Honor,”

“The Episode of the Financial Napoleon” (1916)

A Number Three company of Grumpy or Sherlock Holmes or Lightnin’ would be worth seeing, but it is impossible to imagine The Cat-Bird without John Drew.

“The New Plays” (1920)

…sprinting down Park Lane with the mob after me with dripping knives (Ch.6; page 62?)

Comrade Prebble, in chapter 15 of Psmith in the City, addresses a crowd on Clapham Common, who “roared with happy laughter when he urged them to march upon Park Lane and loot the same without mercy or scruple.” In “Comrade Bingo” Bingo Little has fallen in love with the daughter of a revolutionary; he tells Bertie: “You must meet old Rowbotham, Bertie. A delightful chap. Wants to massacre the bourgeoisie, sack Park Lane, and disembowel the hereditary aristocracy.” [NM]

thirty miles or so to Bristol (Ch.6; page 63)

This would put us somewhere west of Bridgewater, on the stretch of coast at the northern end of the Quantocks. There is nowhere on this part of the coast with a harbour. Watchet and Minehead would be 40–45 miles from Bristol.

toddling upstairs (Ch.6; page 63)

heliotrope (Ch.6; page 63)

Name given to flowers that turn to follow the sun, especially heliotropium, and hence also to the rich purple colour of these flowers.

https://www.gardening.cornell.edu/homegardening/scene815a.html

Chapter 7

A Visitor for Bertie

Runs from pp. 64 to 71 in the 1999 Penguin edition

woman wailing for her demon lover (Ch.7; page 67)

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

So twice five miles of fertile ground

With walls and towers were girdled round:

And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills,

Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree

And here were forests ancient as the hills,

Enfolding sunny spots of greenery.

But oh! that deep romantic chasm which slanted

Down the green hill athwart a cedarn cover!

A savage place! as holy and enchanted

As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted

By woman wailing for her demon-lover!

And from this chasm, with ceaseless turmoil seething

As if this earth in fast thick pants were breathing,

A mighty fountain momently was forced;

Amid whose swift half-intermitted burst

Huge fragments vaulted like rebounding hail,

Or chaffy grain beneath the thresher’s flail:

And ’mid these dancing rocks at once and ever

It flung up momently the sacred river.

Five miles meandering with a mazy motion

Through wood and dale the sacred river ran,

Then reached the caverns measureless to man,

And sank in tumult to a lifeless ocean:

And ’mid this tumult Kubla heard from far

Ancestral voices prophesying war!

The shadow of the dome of pleasure

Floated midway on the waves;

Where was heard the mingled measure

From the fountain and the caves.

It was a miracle of rare device,

A sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice!

A damsel with a dulcimer

In a vision once I saw:

It was an Abyssinian maid,

And on her dulcimer she played,

Singing of Mount Abora.

Could I revive within me

Her symphony and song,

To such a deep delight ’twould win me,

That with music loud and long,

I would build that done in air,

That sunny dome! those caves of ice!

And all who heard should see them there,

And all should cry, Beware! Beware!

His flashing eyes, his floating hair!

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread,

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834): Kubla Khan

mentally somewhat negligible (Ch.7; page 68?)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

“Tchah!” (Ch.7; page 68?)

This interjection of ”impatience or contempt” [OED] is an alternate spelling of “Pshaw!”; indeed, the Cosmopolitan editor substituted Pshaw! in the US magazine serial.

In both magazines and in the US book, after the first such exclamation, Pauline asks “Have you caught cold?” and Bertie replies “I wasn’t sneezing. I was saying ‘Tchah!’ ” (or ‘Pshaw!’) instead of the simpler “Eh?” and the following line in the UK text. [NM]

the story of the Three Bears (Ch.7; page 69)

This famous story seems to have appeared first in the collection English Fairy Tales (1890), by the Australian-born scholar Joseph Jacobs (1854–1916). In Jacobs’s version it is a little old woman who visits the bears’ cottage; Goldilocks seems to have been added later.

had his licence endorsed (Ch.7; page 69)

A motoring reference: before the introduction of “points,” motorists who were convicted of certain types of driving offence had their driving licences endorsed; collecting too many endorsements would lead to revocation or suspension of the licence.

Obviously Bertie doesn’t count being engaged as incompatible with his bachelor status, otherwise he would have lost his licence long ago...