The Strand Magazine, September 1925

IT was an afternoon on which one would have said that all Nature smiled. The air was soft and balmy; the links, fresh from the rains of spring, glistened in the pleasant sunshine; and down on the second tee young Clifford Wimple, in a new suit of plus-fours, had just sunk two balls in the lake and was about to sink a third. No element, in short, was lacking that might be supposed to make for quiet happiness.

And yet on the forehead of the Oldest Member, as he sat beneath the chestnut tree on the terrace overlooking the ninth green, there was a peevish frown; and his eye, gazing down at the rolling expanse of turf, lacked its customary genial benevolence. His favourite chair, consecrated to his private and personal use by unwritten law, had been occupied by another. That is the worst of a free country—liberty so often degenerates into licence.

The Oldest Member coughed.

“I trust,” he said, “you find that chair comfortable?”

The intruder, who was the club’s hitherto spotless secretary, glanced up in a goofy manner.

“Eh?”

“That chair—you find it fits snugly to the figure?”

“Chair? Figure? Oh, you mean this chair? Oh, yes.”

“I am gratified and relieved,” said the Oldest Member.

There was a silence.

“Look here,” said the secretary, “what would you do in a case like this? You know I’m engaged?”

“I do. And no doubt your fiancée is missing you. Why not go in search of her?”

“She’s the sweetest girl on earth.”

“I should lose no time.”

“But jealous. And just now I was in my office, and that Mrs. Pettigrew came in to ask if there was any news of the purse which she lost a couple of days ago. It had just been brought to my office, so I produced it; whereupon the infernal woman, in a most unsuitably girlish manner, flung her arms round my neck and kissed me on my bald spot. And at that moment Adela came in. Death,” said the secretary, “where is thy sting?”

The Oldest Member’s pique melted. He had a feeling heart.

“Most unfortunate. What did you say?”

“I hadn’t time to say anything. She shot out too quick.”

The Oldest Member clicked his tongue sympathetically.

“These misunderstandings between young and ardent hearts are very frequent,” he said. “I could tell you at least fifty cases of the same kind. The one which I will select is the story of Jane Packard, William Bates, and Rodney Spelvin.”

“You told me that the other day. Jane Packard got engaged to Rodney Spelvin, the poet, but the madness passed and she married William Bates, who was a golfer.”

“This is another story of the trio.”

“You told me that one, too. After Jane Packard married William Bates she fell once more under the spell of Spelvin, but repented in time.”

“This is still another story. Making three in all.”

The secretary buried his face in his hands.

“Oh, well,” he said, “go ahead. What does anything matter now?”

“First,” said the Oldest Member, “let us make ourselves comfortable. Take this chair. It is easier than the one in which you are sitting.”

“No, thanks.”

“I insist.”

“Oh, all right.”

“Woof!” said the Oldest Member, settling himself luxuriously.

With an eye now full of kindly good-will, he watched young Clifford Wimple play his fourth. Then, as the silver drops flashed up into the sun, he nodded approvingly and began.

THE story which I am about to relate (said the Oldest Member) begins at a time when Jane and William had been married some seven years. Jane’s handicap was eleven, William’s twelve, and their little son, Braid Vardon, had just celebrated his sixth birthday.

Ever since that dreadful time, two years before, when, lured by the glamour of Rodney Spelvin, she had taken a studio in the artistic quarter, dropped her golf, and practically learned to play the ukelele, Jane had been unremitting in her efforts to be a good mother and to bring up her son on the strictest principles. And, in order that his growing mind might have every chance, she had invited William’s younger sister, Anastatia, to spend a week or two with them and put the child right on the true functions of the mashie. For Anastatia had reached the semi-finals of the last Ladies’ Open Championship and, unlike many excellent players, had the knack of teaching.

On the evening on which this story opens the two women were sitting in the drawing-room, chatting. They had finished tea; and Anastatia, with the aid of a lump of sugar, a spoon, and some crumbled cake, was illustrating the method by which she had got out of the rough on the fifth at Squashy Hollow.

“You’re wonderful!” said Jane, admiringly. “And such a good influence for Braid! You’ll give him his lesson tomorrow afternoon as usual?”

“I shall have to make it the morning,” said Anastatia. “I’ve promised to meet a man in town in the afternoon.”

As she spoke there came into her face a look so soft and dreamy that it roused Jane as if a bradawl had been driven into her leg. As her history has already shown, there was a strong streak of romance in Jane Bates.

“Who is he?” she asked, excitedly.

“A man I met last summer,” said Anastatia.

And she sighed with such abandon that Jane could no longer hold in check her womanly nosiness.

“Do you love him?” she cried.

“Like bricks,” whispered Anastatia.

“Does he love you?”

“Sometimes I think so.”

“What’s his name?”

“Rodney Spelvin.”

“What!”

“Oh, I know he writes the most awful bilge,” said Anastatia, defensively, misinterpreting the yowl of horror which had proceeded from Jane. “All the same, he’s a darling.”

Jane could not speak. She stared at her sister-in-law aghast. Although she knew that if you put a driver in her hands she could paste the ball into the next county, there always seemed to her something fragile and helpless about Anastatia. William’s sister was one of those small, rose-leaf girls with big blue eyes to whom good men instinctively want to give a stroke a hole and on whom bad men automatically prey. And when Jane reflected that Rodney Spelvin had to all intents and purposes preyed upon herself, who stood five foot seven in her shoes and, but for an innate love of animals, could have felled an ox with a blow, she shuddered at the thought of how he would prey on this innocent half-portion.

“You really love him?” she quavered.

“If he beckoned to me in the middle of a medal round, I would come to him,” said Anastatia.

“If he beckoned to me in the middle of a medal round, I would come to him,” said Anastatia.

Jane realized that further words were useless. A sickening sense of helplessness obsessed her. Something ought to be done about this terrible thing, but what could she do? She was so ashamed of her past madness that not even to warn this girl could she reveal that she had once been engaged to Rodney Spelvin herself; that he had recited poetry on the green while she was putting; and that, later, he had hypnotized her into taking William and little Braid to live in a studio full of samovars. These revelations would no doubt open Anastatia’s eyes, but she could not make them.

And then, suddenly, Fate pointed out a way.

It was Jane’s practice to go twice a week to the cinema palace in the village; and two nights later she set forth as usual and took her place just as the entertainment was about to begin.

At first she was only mildly interested. The title of the picture, “Tried in the Furnace,” had suggested nothing to her. Being a regular patron of the silver screen, she knew that it might quite easily turn out to be an educational film on the subject of clinker-coal. But as the action began to develop she found herself leaning forward in her seat, blindly crushing a caramel between her fingers. For scarcely had the operator started to turn the crank when inspiration came to her.

Of the main plot of “Tried in the Furnace” she retained, when finally she reeled out into the open air, only a confused recollection. It had something to do with money not bringing happiness or happiness not bringing money, she could not remember which. But the part which remained graven upon her mind was the bit where Gloria Gooch goes by night to the apartments of the libertine, to beg him to spare her sister, whom he has entangled in his toils.

Jane saw her duty clearly. She must go to Rodney Spelvin and conjure him by the memory of their ancient love to spare Anastatia.

IT was not the easiest of tasks to put this scheme into operation. Gloria Gooch, being married to a scholarly man who spent nearly all his time in a library a hundred yards long, had been fortunately situated in the matter of paying visits to libertines; but for Jane the job was more difficult. William expected her to play a couple of rounds with him in the morning and another in the afternoon, which rather cut into her time. However, Fate was still on her side, for one morning at breakfast William announced that business called him to town.

“Why don’t you come, too?” he said.

Jane started.

“No. No, I don’t think I will, thanks.”

“Give you lunch somewhere.”

“No. I want to stay here and do some practice-putting.”

“All right. I’ll try to get back in time for a round in the evening.”

Remorse gnawed at Jane’s vitals. She had never deceived William before. She kissed him with even more than her usual fondness when he left to catch the ten-forty-five. She waved to him till he was out of sight; then, bounding back into the house, leaped at the telephone and, after a series of conversations with the Marks-Morris Glue Factory, the Poor Pussy Home for Indigent Cats, and Messrs. Oakes, Oakes, and Parbury, dealers in fancy goods, at last found herself in communication with Rodney Spelvin.

“Rodney?” she said, and held her breath, fearful at this breaking of a two years’ silence and yet loath to hear another strange voice say “Wadnumjerwant?” “Is that you, Rodney?”

“Yes. Who is that?”

“Mrs. Bates. Rodney, can you give me lunch at the Alcazar to-day at one?”

“Can I!” Not even the fact that some unknown basso had got on the wire and was asking if that was Mr. Bootle could blur the enthusiasm in his voice. “I should say so!”

“One o’clock, then,” said Jane. His enthusiastic response had relieved her. If by merely speaking she could stir him so, to bend him to her will when they met face to face would be pie.

“One o’clock,” said Rodney.

Jane hung up the receiver and went to her room to try on hats.

THE impression came to Jane, when she entered the lobby of the restaurant and saw him waiting, that Rodney Spelvin looked somehow different from the Rodney she remembered. His handsome face had a deeper and more thoughtful expression, as if he had been through some ennobling experience.

“Well, here I am,” she said, going to him and affecting a jauntiness which she did not feel.

He looked at her, and there was in his eyes that unmistakable goggle which comes to men suddenly addressed in a public spot by women whom, to the best of their recollection, they do not know from Eve.

“How are you?” he said. He seemed to pull himself together. “You’re looking splendid.”

“You’re looking fine,” said Jane.

“You’re looking awfully well,” said Rodney.

“You’re looking awfully well,” said Jane.

“You’re looking fine,” said Rodney.

There was a pause.

“You’ll excuse me glancing at my watch,” said Rodney. “I have an appointment to lunch with—er—somebody here, and it’s past the time.”

“But you’re lunching with me,” said Jane, puzzled.

“With you?”

“Yes. I rang you up this morning.”

Rodney gaped.

“Was it you who ’phoned? I thought you said ‘Miss Bates.’ ”

“No, Mrs. Bates.”

“Mrs. Bates?”

“Mrs. Bates.”

“Of course. You’re Mrs. Bates.”

“Had you forgotten me?” said Jane, in spite of herself a little piqued.

“Forgotten you, dear lady! As if I could!” said Rodney, with a return of his old manner. “Well, shall we go in and have lunch?”

“All right,” said Jane.

She felt embarrassed and ill at ease. The fact that Rodney had obviously succeeded in remembering her only after the effort of a lifetime seemed to her to fling a spanner into the machinery of her plans at the very outset. It was going to be difficult, she realized, to conjure him by the memory of their ancient love to spare Anastatia; for the whole essence of the idea of conjuring anyone by the memory of their ancient love is that the party of the second part should be aware that there ever was such a thing.

At the luncheon-table conversation proceeded fitfully. Rodney said that this morning he could have sworn it was going to rain, and Jane said she had thought so, too, and Rodney said that now it looked as if the weather might hold up, and Jane said Yes, didn’t it? and Rodney said he hoped the weather would hold up because rain was such a nuisance, and Jane said Yes, wasn’t it? Rodney said yesterday had been a nice day, and Jane said Yes, and Rodney said that it seemed to be getting a little warmer, and Jane said Yes, and Rodney said that summer would be here any moment now, and Jane said Yes. wouldn’t it? and Rodney said he hoped it would not be too hot this summer, but that, as a matter of fact, when you came right down to it, what one minded was not so much the heat as the humidity, and Jane said Yes, didn’t one?

In short, by the time they rose and left the restaurant, not a word had been spoken that could have provoked the censure of the sternest critic. Yet William Bates, catching sight of them as they passed down the aisle, started as if he had been struck by lightning. He had happened to find himself near the Alcazar at lunch-time and had dropped in for a chop; and, peering round the pillar which had hidden his table from theirs, he stared after them with saucer-like eyes.

In short, by the time they rose and left the restaurant, not a word had been spoken that could have provoked the censure of the sternest critic. Yet William Bates, catching sight of them as they passed down the aisle, started as if he had been struck by lightning. He had happened to find himself near the Alcazar at lunch-time and had dropped in for a chop; and, peering round the pillar which had hidden his table from theirs, he stared after them with saucer-like eyes.

“Oh, dash it!” said William.

This William Bates, as I have indicated in my previous references to him, was not an abnormally emotional or temperamental man. Built physically on the lines of a motor-lorry, he had much of that vehicle’s placid and even phlegmatic outlook on life. Few things had the power to ruffle William, but, unfortunately, it so happened that one of these things was Rodney Spelvin. He had never been able entirely to overcome his jealousy of this man. It had been Rodney who had come within an ace of scooping Jane from him in the days when she had been Miss Packard. It had been Rodney who had temporarily broken up his home some years later by persuading Jane to become a member of the artistic set. And now, unless his eyes jolly well deceived him, this human gumboil was once more busy on his dastardly work. Too dashed thick, was William’s view of the matter; and he gnashed his teeth in such a spasm of resentful fury that a man lunching at the next table told the waiter to switch off the electric fan, as it had begun to creak unendurably.

JANE was reading in the drawing-room when William reached home that night.

“Had a nice day?” asked William.

“Quite nice,” said Jane.

“Play golf?” asked William.

“Just practised,” said Jane.

“Lunch at the club?”

“Yes.”

“I thought I saw that bloke Spelvin in town,” said William. Jane wrinkled her forehead.

“Spelvin? Oh, you mean Rodney Spelvin? Did you? I see he’s got a new book coming out.”

“You never run into him these days, do you?”

“Oh, no. It must be two years since I saw him.”

“Oh?” said William. “Well, I’ll be going upstairs and dressing.”

It seemed to Jane, as the door closed, that she heard a curious clicking noise, and she wondered for a moment if little Braid had got out of bed and was playing with the Mah-Jongg counters. But it was only William gnashing his teeth.

THERE is nothing sadder in this life than the spectacle of a husband and wife with practically identical handicaps drifting apart; and to dwell unnecessarily on such a spectacle is, to my mind, ghoulish. It is not my purpose, therefore, to weary you with a detailed description of the hourly widening of the breach between this once ideally united pair. Suffice it to say that within a few days of the conversation just related the entire atmosphere of this happy home had completely altered. On the Tuesday, William excused himself from the morning round on the plea that he had promised Peter Willard a match, and Jane said What a pity! On Tuesday afternoon William said that his head ached, and Jane said Isn’t that too bad? On Wednesday morning William said he had lumbago, and Jane, her sensitive feelings now deeply wounded, said Oh, had he? After that, it came to be agreed between them by silent compact that they should play together no more.

Also, they began to avoid one another in the house. Jane would sit in the drawing-room, while William retired down the passage to his den. In short, if you had added a couple of ikons and a photograph of Trotsky, you would have had a mise en scène which would have fitted a Russian novel like the paper on the wall.

One evening, about a week after the beginning of this tragic state of affairs, Jane was sitting in the drawing-room, trying to read Braid on Casual Water. But the print seemed blurred and the philosophy too metaphysical to be grasped. She laid the book down and stared sadly before her.

Every moment of these black days had affected Jane like a stymie on the last green. She could not understand how it was that William should have come to suspect, but that he did suspect was plain; and she writhed on the horns of a dilemma. All she had to do to win him back again was to go to him and tell him of Anastatia’s fatal entanglement. But what would happen then? Undoubtedly he would feel it his duty as a brother to warn the girl against Rodney Spelvin; and Jane instinctively knew that William warning anyone against Rodney Spelvin would sound like a private of the line giving his candid opinion of the sergeant-major.

Inevitably, in this case, Anastatia, a spirited girl and deeply in love, would take offence at his words and leave the house. And if she left the house, what would be the effect on little Braid’s mashie-play? Already, in less than a fortnight, the gifted girl had taught him more about the chip-shot from ten to fifteen yards off the green than the local pro. had been able to do in two years. Her departure would be absolutely disastrous.

What it amounted to was that she must sacrifice her husband’s happiness or her child’s future; and the problem of which was to get the loser’s end was becoming daily more insoluble.

She was still brooding on it when the postman arrived with the evening mail, and the maid brought the letters into the drawing-room.

Jane sorted them out. There were three for William, which she gave to the maid to take to him in his den. There were two for herself, both bills. And there was one for Anastatia, in the well-remembered handwriting of Rodney Spelvin.

Jane placed this letter on the mantelpiece, and stood looking at it like a cat at a canary. Anastatia was away for the day, visiting friends who lived a few stations down the line; and every womanly instinct in Jane urged her to get hold of a kettle and steam the gum off the envelope. She had almost made up her mind to disembowel the thing and write “Opened in error” on it, when the telephone suddenly went off like a bomb and nearly startled her into a decline. Coming at that moment, it sounded like the Voice of Conscience.

“Hullo?” said Jane.

“Hullo!” replied a voice.

Jane clucked like a hen with uncontrollable emotion. It was Rodney.

“Is that you?” asked Rodney.

“Yes,” said Jane.

And so it was, she told herself.

“Your voice is like music,” said Rodney.

This may or may not have been the case, but at any rate it was exactly like every other female voice when heard on the telephone. Rodney prattled on without a suspicion.

“Have you got my letter yet?”

“No,” said Jane. She hesitated. “What was in it?” she asked, tremulously.

“It was to ask you to come to my house to-morrow at four.”

“To your house!” faltered Jane.

“Yes. Everything is ready. I will send the servants out, so that we shall be quite alone. You will come, won’t you?”

The room was shimmering before Jane’s eyes, but she regained command of herself with a strong effort.

“Yes,” she said. “I will be there.”

She spoke softly, but there was a note of menace in her voice. Yes, she would indeed be there. From the very moment when this man had made his monstrous proposal, she had been asking herself what Gloria Gooch would have done in a crisis like this. And the answer was plain. Gloria Gooch, if her sister-in-law was intending to visit the apartments of a libertine, would have gone there herself to save the poor child from the consequences of her infatuated folly.

“Yes,” said Jane, “I will be there.”

“You have made me the happiest man in the world,” said Rodney. “I will meet you at the corner of the street at four, then.” He paused. “What is that curious clicking noise?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” said Jane. “I noticed it myself. Something wrong with the wire, I suppose.”

“I thought it was somebody playing the castanets. Until to-morrow, then, goodbye.”

“Good-bye.”

Jane replaced the receiver. And William, who had been listening to every word of the conversation on the extension in his den, replaced his receiver, too.

ANASTATIA came back from her visit late that night. She took her letter, and read it without comment. At breakfast next morning she said that she would be compelled to go into town that day.

“I want to see my dressmaker,” she said.

“I’ll come, too,” said Jane. “I want to see my dentist.”

“So will I,” said William. “I want to see my lawyer.”

“That will be nice,” said Anastatia, after a pause.

“Very nice,” said Jane, after another pause.

“We might all lunch together,” said Anastatia. “My appointment is not till four.”

“I should love it,” said Jane. “My appointment is at four, too.”

“So is mine,” said William.

“What a coincidence!” said Jane, trying to speak brightly.

“Yes,” said William. He may have been trying to speak brightly, too; but, if so, he failed. Jane was too young to have seen Salvini in “Othello,” but, had she witnessed that great tragedian’s performance, she could not have failed to be struck by the resemblance between his manner in the pillow scene and William’s now.

“Then shall we all lunch together?” said Anastatia.

“I shall lunch at my club,” said William, curtly.

“William seems to have a grouch,” said Anastatia.

“Ha!” said William.

He raised his fork and drove it with sickening violence at his sausage.

SO Jane had a quiet little woman’s lunch at a confectioner’s alone with Anastatia. Jane ordered a tongue-and-lettuce sandwich, two macaroons, marsh-mallows, ginger-ale, and cocoa; and Anastatia ordered pineapple chunks with whipped cream, tomatoes stuffed with beetroot, three dill pickles, a raspberry nut sundae, and hot chocolate. And, while getting outside this garbage, they talked merrily, as women will, of every subject but the one that really occupied their minds. When Anastatia got up and said good-bye with a final reference to her dressmaker, Jane shuddered at the depths of deceit to which the modern girl can sink.

It was now about a quarter to three, so Jane had an hour to kill before going to the rendezvous. She wandered about the streets, and never had time appeared to her to pass so slowly, never had a city been so congested with hard-eyed and suspicious citizens. Every second person she met seemed to glare at her as if he or she had guessed her secret.

The very elements joined in the general disapproval. The sky had turned a sullen grey, and far-away thunder muttered faintly, like an impatient golfer held up on the tee by a slow foursome. It was a relief when at length she found herself at the back of Rodney Spelvin’s house, standing before the scullery window, which it was her intention to force with the pocket-knife won in happier days as second prize in a competition at a summer hotel for those with handicaps above eighteen.

But the relief did not last long. Despite the fact that she was about to enter this evil house with the best motives, a sense of almost intolerable guilt oppressed her. If William should ever get to know of this! Wow! felt Jane.

How long she would have hesitated before the window, one cannot say. But at this moment, glancing guiltily round, she happened to catch the eye of a cat which was sitting on a near-by wall, and she read in this cat’s eye such cynical derision that the urge came upon her to get out of its range as quickly as possible. It was a cat that had manifestly seen a lot of life, and it was plainly putting an entirely wrong construction on her behaviour. Jane shivered, and with a quick jerk prised the window open and climbed in.

It was two years since she had entered this house, but once she had reached the hall she remembered its topography perfectly. She mounted the stairs to the large studio sitting-room on the first floor, the scene of so many Bohemian parties in that dark period of her artistic life. It was here, she knew, that Rodney would bring his victim.

The studio was one of those dim, over-ornamented rooms which appeal to men like Rodney Spelvin. Heavy curtains hung in front of the windows. One corner was cut off by a high-backed Chesterfield. At the far end was an alcove, curtained like the windows. Once Jane had admired this studio, but now it made her shiver. It seemed to her one of those nests in which, as the sub-title of “Tried in the Furnace” had said, only eggs of evil are hatched. She paced the thick carpet restlessly, and suddenly there came to her the sound of footsteps on the stairs.

Jane stopped, every muscle tense. The moment had arrived. She faced the door, tight-lipped. It comforted her a little in this crisis to reflect that Rodney was not one of those massive Ethel M. Dell libertines who might make things unpleasant for an intruder. He was only a welter-weight egg of evil; and, if he tried to start anything, a girl of her physique would have little or no difficulty in knocking the stuffing out of him.

The footsteps reached the door. The handle turned. The door opened. And in strode William Bates, followed by two men in bowler hats.

“Ha!” said William.

Jane’s lips parted, but no sound came from them. She staggered back a pace or two. William, advancing into the centre of the room, folded his arms and gazed at her with burning eyes.

“So,” said William, and the words seemed forced like drops of vitriol from between his clenched teeth, “I find you here, dash it!”

Jane choked convulsively. Years ago, when an innocent child, she had seen a conjurer produce a rabbit out of a top-hat which an instant before had been conclusively proved to be empty. The sudden apparition of William affected her with much the same sensations as she had experienced then.

“How-ow-ow——?” she said.

“I beg your pardon?” said William, coldly.

“How-ow-ow——?”

“Explain yourself,” said William.

“How-ow-ow did you get here? And who-oo-oo are these men?”

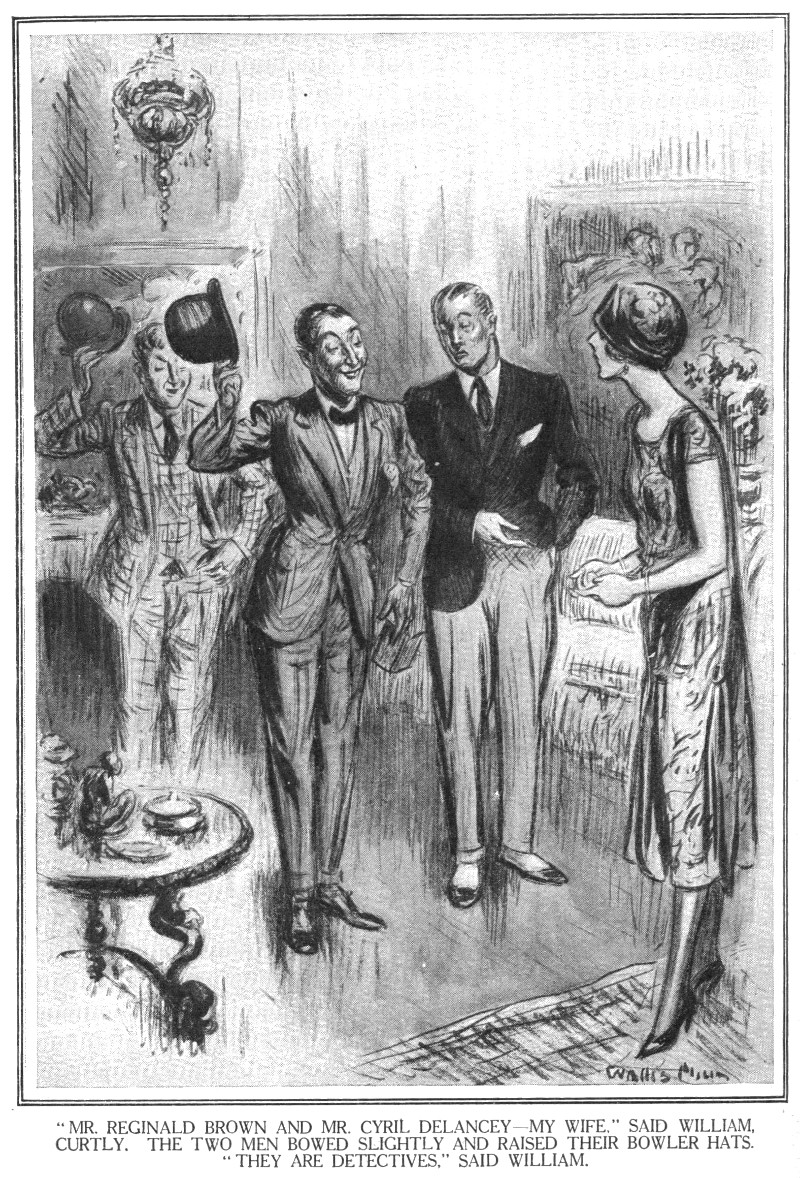

William seemed to become aware for the first time of the presence of his two companions. He moved a hand in a hasty gesture of introduction.

“Mr. Reginald Brown and Mr. Cyril Delancey—my wife,” he said, curtly.

The two men bowed slightly and raised their bowler hats.

“Pleased to meet you,” said one.

“Most awfully charmed,” said the other.

“They are detectives,” said William.

“Detectives!”

“From the Quick Results Agency.”

“Limited,” added Mr. Delancey.

“Limited,” said William. “When I became aware of your clandestine intrigues, I went to the agency and they gave me their two best men.”

“Oh, well,” said Mr. Brown, blushing a little.

“Most frightfully decent of you to put it that way,” said Mr. Delancey.

William regarded Jane sternly.

“I knew you were going to be here at four o’clock,” he said. “I overheard you making the assignation on the telephone.”

“Oh, William!”

“Woman,” said William, “where is your paramour?”

“Really, really,” said Mr. Delancey, deprecatingly.

“Keep it clean,” urged Mr. Brown.

“Your partner in sin, where is he? I am going to take him and tear him into little bits and stuff him down his throat and make him swallow himself.”

“Fair enough,” said Mr. Brown.

“Perfectly in order,” said Mr. Delancey.

Jane uttered a stricken cry.

“William,” she screamed, “I can explain all.”

“All?” said Mr. Delancey.

“All?” said Mr. Brown.

“All,” said Jane.

“All?” said William.

“All,” said Jane.

William sneered bitterly.

“I’ll bet you can’t,” he said.

“I’ll bet I can,” said Jane.

“Well?”

“I came here to save Anastatia.”

“Anastatia!”

“Anastatia.”

“My sister?”

“Your sister.”

“His sister Anastatia,” explained Mr. Brown to Mr. Delancey in an undertone.

“What from?” asked William.

“From Rodney Spelvin. Oh, William, can’t you understand?”

“No, I’m dashed if I can.”

“I, too,” said Mr. Delancey, “must confess myself a little fogged. And you, Reggie?”

“Completely, Cyril,” said Mr. Brown, removing his bowler hat with a puzzled frown, examining the maker’s name, and putting it on again.

“The poor child is infatuated with this man.”

“With the bloke Spelvin?”

“Yes. She is coming here with him at four o’clock.”

“Important,” said Mr. Brown, producing a note-book and making an entry.

“Important, if true,” agreed Mr. Delancey.

“But I heard you making the appointment with the bloke Spelvin over the ’phone,” said William.

“He thought I was Anastatia. And I came here to save her.”

WILLIAM was silent and thoughtful for a few moments.

“It all sounds very nice and plausible,” he said, “but there’s just one thing wrong. I’m not a very clever sort of bird, but I can see where your story slips up. If what you say is true, where is Anastatia?”

“Just coming in now,” whispered Jane. “Hist!”

“Hist, Reggie!” whispered Mr. Delancey.

They listened. Yes, the front door had banged, and feet were ascending the staircase.

“Hide!” said Jane, urgently.

“Why?” said William.

“So that you can overhear what they say and jump out and confront them.”

“Sound,” said Mr. Delancey.

“Very sound,” said Mr. Brown.

The two detectives concealed themselves in the alcove. William retired behind the curtains in front of the window. Jane dived behind the Chesterfield. A moment later the door opened.

Crouching in her corner, Jane could see nothing, but every word that was spoken came to her ears; and with every syllable her horror deepened.

“Give me your things,” she heard Rodney say, “and then we will go upstairs.”

Jane shivered. The curtains by the window shook. From the direction of the alcove there came a soft scratching sound, as the two detectives made an entry in their note-books.

For a moment after this there was silence. Then Anastatia uttered a sharp, protesting cry.

“Ah, no, no! Please, please!”

“But why not?” came Rodney’s voice.

“It is wrong—wrong.”

“I can’t see why.”

“It is, it is! You must not do that. Oh, please, please don’t hold so tight.”

There was a swishing sound, and through the curtains before the window a large form burst. Jane raised her head above the Chesterfield.

William was standing there, a menacing figure. The two detectives had left the alcove and were moistening their pencils. And in the middle of the room stood Rodney Spelvin, stooping slightly and grasping Anastatia’s parasol in his hands.

“I don’t get it,” he said. “Why is it wrong to hold the dam’ thing tight?” He looked up and perceived his visitors. “Ah, Bates,” he said, absently. He turned to Anastatia again. “I should have thought that the tighter you held it, the more force you would get into the shot.”

“But don’t you see, you poor zimp,” replied Anastatia, “that you’ve got to keep the ball straight. If you grip the shaft as if you were a drowning man clutching at a straw and keep your fingers under like that, you’ll pull like the dickens and probably land out of bounds or in the rough. What’s the good of getting force into the shot if the ball goes in the wrong direction, you cloth-headed goof?”

“I see now,” said Rodney, humbly. “How right you always are!”

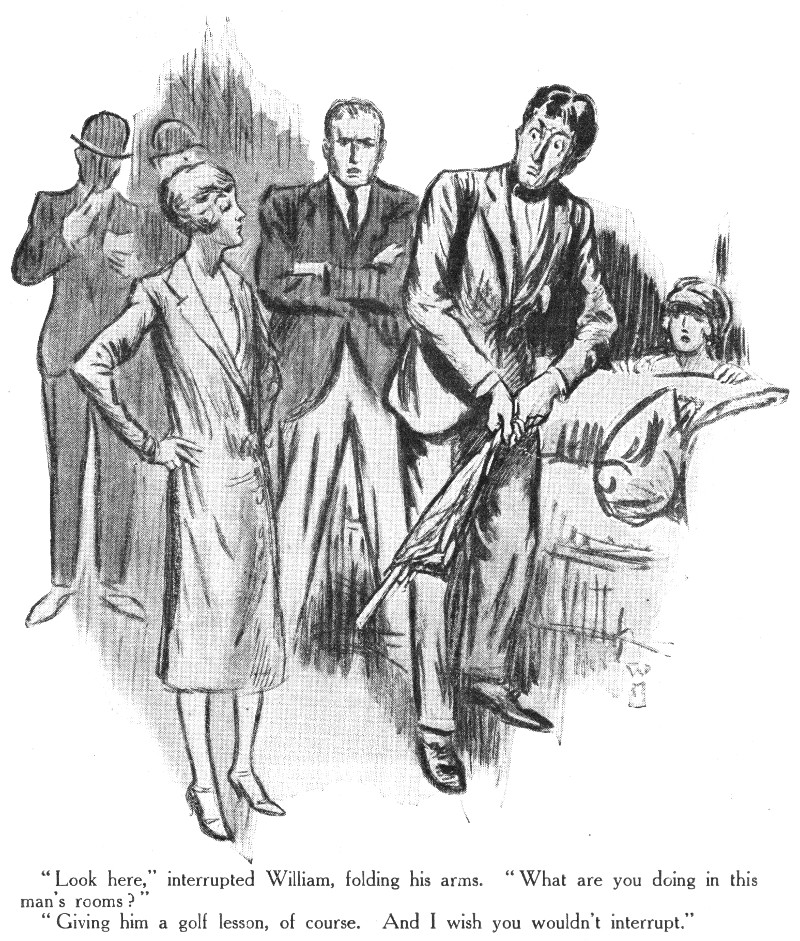

“Look here,” interrupted William, folding his arms. “What is the meaning of this?”

“You want to grip firmly but lightly,” said Anastatia.

“Firmly but lightly,” echoed Rodney.

“What is the meaning of this?”

“And with the fingers. Not with the palms.”

“What is the meaning of this?” thundered William. “Anastatia, what are you doing in this man’s rooms?”

“Giving him a golf lesson, of course. And I wish you wouldn’t interrupt.”

“Yes, yes,” said Rodney, a little testily. “Don’t interrupt, Bates, there’s a good fellow. Surely you have things to occupy you elsewhere?”

“We’ll go upstairs,” said Anastatia, “where we can be alone.”

“You will not go upstairs,” barked William.

“We shall get on much better there,” explained Anastatia. “Rodney has fitted up the top-floor back as an indoor practising room.”

Jane darted forward with a maternal cry.

“My poor child, has this scoundrel dared to delude you by pretending to be a golfer? Darling, he is nothing of the kind.”

Mr. Reginald Brown coughed. For some moments he had been twitching restlessly.

“Talking of golf,” he said, “it might interest you to hear of a little experience I had the other day at Marshy Moor. I had got a nice drive off the tee, nothing record-breaking, you understand, but straight and sweet. And what was my astonishment on walking up to play my second to find——”

“A rather similar thing happened to me at Windy Waste last Tuesday,” interrupted Mr. Delancey. “I had hooked my drive the merest trifle, and my caddie said to me, ‘You’re out of bounds.’ ‘I am not out of bounds,’ I replied, perhaps a little tersely, for the lad had annoyed me by a persistent habit of sniffing. ‘Yes, you are out of bounds,’ he said. ‘No, I am not out of bounds,’ I retorted. Well, believe me or believe me not, when I got up to my ball——”

“Shut up!” said William.

“Just as you say, sir,” replied Mr. Delancey, courteously.

RODNEY SPELVIN drew himself up, and in spite of her loathing for his villainy Jane could not help feeling what a noble and romantic figure he made. His face was pale, but his voice did not falter.

“You are right,” he said. “I am not a golfer. But with the help of this splendid girl here, I hope humbly to be one some day. Ah, I know what you are going to say,” he went on, raising a hand. “You are about to ask how a man who has wasted his life as I have done can dare to entertain the mad dream of ever acquiring a decent handicap. But never forget,” proceeded Rodney, in a low, quivering voice, “that Walter J. Travis was nearly forty before he touched a club, and a few years later he won the British Amateur.”

“True,” murmured William.

“True, true,” said Mr. Delancey and Mr. Brown. They lifted their bowler hats reverently.

“I am thirty-three years old,” continued Rodney, “and for fourteen of those thirty-three years I have been writing poetry—aye, and novels with a poignant sex-appeal, and if ever I gave a thought to this divine game it was but to sneer at it. But last summer I saw the light.”

“Glory! Glory!” cried Mr. Brown.

“One afternoon I was persuaded to try a drive. I took the club with a mocking, contemptuous laugh.” He paused, and a wild light came into his eyes. “I brought off a perfect snifter,” he said, emotionally. “Two hundred yards and as straight as a whistle. And, as I stood there gazing after the ball, something seemed to run up my spine and bite me in the neck. It was the golf-germ.”

“Always the way,” said Mr. Brown. “I remember the first drive I ever made. I took a nice easy stance——”

“The first drive I made,” said Mr. Delancey, “you won’t believe this, but it’s a fact, was a full——”

“From that moment,” continued Rodney Spelvin, “I have had but one ambition—to somehow or other, cost what it might, get down into single figures.” He laughed bitterly. “You see,” he said, “I cannot even speak of this thing without splitting my infinitives. And, even as I split my infinitives, so did I split my drivers. After that first heavenly slosh I didn’t seem able to do anything right.”

He broke off, his face working. William cleared his throat awkwardly.

“Yes, but, dash it,” he said, “all this doesn’t explain why I find you alone with my sister in what I might call your lair.”

“The explanation is simple,” said Rodney Spelvin. “This sweet girl is the only person in the world who seems able to simply and intelligently and in a few easily understood words make clear the knack of the thing. There is none like her, none. I have been to pro. after pro., but not one has been any good to me. I am a temperamental man, and there is a lack of sympathy and human understanding about these professionals which jars on my artist soul. They look at you as if you were a half-witted child. They click their tongues. They make odd Scotch noises. I could not endure the strain. And then this wonderful girl, to whom in a burst of emotion I had confided my unhappy case, offered to give me private lessons. So I went with her to some of those indoor practising places. But here, too, my sensibilities were racked by the fact that unsympathetic eyes observed me. So I fixed up a room here where we could be alone.”

“And, instead of going there,” said Anastatia, “we are wasting half the afternoon talking.”

William brooded for a while. He was not a quick thinker.

“Well, look here,” he said at length, “this is the point. This is the nub of the thing. This is where I want you to follow me very closely. Have you asked Anastatia to marry you?”

“Marry me?” Rodney gazed at him, shocked. “Have I asked her to marry me? I, who am not worthy to polish the blade of her niblick! I, who have not even a thirty handicap, ask a girl to marry me who was in the semi-final of last year’s Ladies’ Open! No, no, Bates, I may be a vers-libre poet, but I have some sense of what is fitting. I love her, yes. I love her with a fervour which causes me to frequently and for hours at a time lie tossing sleeplessly upon my pillow. But I would not dare to ask her to marry me.”

Anastatia burst into a peal of girlish laughter.

“You poor chump!” she cried. “Is that what has been the matter all this time? I couldn’t make out what the trouble was. Why, I’m crazy about you. I’ll marry you any time you give the word.”

Rodney reeled.

“What!”

“Of course I will.”

“Anastatia!”

“Rodney!”

He folded her in his arms.

“Well, I’m dashed,” said William. “It looks to me as if I had been making rather a lot of silly fuss about nothing. Jane, I wronged you.”

“It was my fault.”

“No, no!”

“Yes, yes!”

“Jane!”

“William!”

He folded her in his arms. The two detectives, having entered the circumstances in their note-books, looked at one another with moist eyes.

“Cyril!” said Mr. Brown.

“Reggie!” said Mr. Delancey.

Their hands met in a brotherly clasp.

“ AND so,” concluded the Oldest Member, “all ended happily. The storm-tossed lives of William Bates, Jane Packard, and Rodney Spelvin came safely at long last into harbour. At the subsequent wedding, William and Jane’s present of a complete golfing outfit, including eight dozen new balls, a cloth cap, and a pair of spiked shoes, was generally admired by all who inspected the gifts during the reception.

“From that time forward the four of them have been inseparable. Rodney and Anastatia took a little cottage close to that of William and Jane, and rarely does a day pass without a close foursome between the two couples. William and Jane being steady tens and Anastatia scratch and Rodney a persevering eighteen, it makes an ideal match.”

“What does?” asked the secretary, waking from his reverie.

“This one.”

“Which?”

“I see,” said the Oldest Member, sympathetically, “that your troubles, weighing on your mind, have caused you to follow my little narrative less closely than you might have done. Never mind, I will tell it again.

“The story” (said the Oldest Member) “which I am about to relate begins at a time when——”

Notes:

A very similar version of the story appeared in the Saturday Evening Post, August 22, 1925; in that version, Miss Bates’s name is spelled Anastasia.

See A Glossary of Golf Terminology on this site for explanations of specific golfing jargon.

all Nature smiled: Frequent in Wodehouse throughout his career; below are early and late examples from at least a dozen usages. See A Damsel in Distress for a literary source.

You would have said that all Nature smiled.

Psmith, Journalist, ch. 18 (1915 in book form, 1910 in magazine serial)

In a word, all Nature smiled, but not so broadly as did Chimp as he sauntered to the garage to smoke a cigarette.

Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin, ch. 10.2 (1972)

plus-fours: see Lord Emsworth and Others.

Death … where is thy sting?: see Biblia Wodehousiana.

You told me that: The two previous stories are “Rodney Fails to Qualify” and “Jane Gets Off the Fairway” (both 1924).

Braid Vardon: His given names honor champion golfers; see The Clicking of Cuthbert.

dreadful time, two years before: Recounted in “Jane Gets Off the Fairway” (1924). Another clue that the internal timeline of the Wodehouse stories is unrelated to the dates of publication.

Squashy Hollow: A fictitious golf course often mentioned by Wodehouse; the first reference seems to be “Rodney Fails to Qualify” and the last is apparently “Sleepy Time” (1965; in Plum Pie). Its name is possibly a reference to a portion of the Sound View golf course in Great Neck, Long Island, New York, where Wodehouse played regularly from 1918 to 1921. A map in In Search of Blandings by N.T.P. Murphy shows an area of marshy grass near the first, seventeenth, and eighteenth holes.

a man in town: Thus in UK magazine and in both book versions; a man in The City in the US magazine, referring to London’s financial district.

bradawl: See A Damsel in Distress.

Like bricks: Shortened form of the cliché like a ton of bricks; that is, having an impact like the delivery of such a heavy load.

give a stroke a hole: This expression suggests that a round of golf would be scored by the rules of match play, in which the outcome is determined by scoring the number of holes won, lost, or tied, rather than the total number of strokes taken. The handicap given to the supposedly weaker player would then be distributed equally among the holes.

could have felled an ox with a blow: See Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit.

medal round: a golf game scored by the total number of strokes taken; see Medal play. Leaving in the middle is mentioned here because a medal round’s outcome cannot be determined until the last hole is finished, whereas in match play the game can terminate early (or the outcome can be assured early) if one player is ahead by more holes than are remaining to play. For instance, if after the twelfth hole of an eighteen-hole round, the match score is ten holes to two, the leader is “eight up and six to play” meaning that there is no way the other player can catch up and win the round.

Tried in the Furnace: see Biblia Wodehousiana. Note also that Wodehouse used the phrase as a short-story title in 1935, collected in Young Men in Spats (UK edition, 1936) and The Crime Wave at Blandings (US, 1937).

operator … turn the crank: By 1925, the larger theatres would use motorized projectors, though as films were still silent the motors often had variable speed controls. In a village cinema, the projector might well be an older hand-cranked model as described here.

Alcazar: There is a famous restaurant of that name in Paris, but no such establishment has so far been discovered in the London of that time, so this seems to be intended fictitiously.

would be pie: See Carry On, Jeeves.

a spanner into the machinery: see Leave It to Psmith.

not so much the heat as the humidity: See Sam the Sudden.

motor-lorry: motortruck in US magazine version only.

phlegmatic: See Right Ho, Jeeves.

within an ace: see Leave It to Psmith.

when she had been Miss Packard: in “Jane Gets Off the Fairway” (1924)

gumboil: see The Mating Season.

Mah-Jongg: A table game played with a set of 144 tiles (small rectangles similar to dominoes in shape; originally ivory, now plastic) decorated with Chinese characters and symbols, based on older Asian games. The modern version was introduced in the USA and UK in 1920 and quickly became a fad.

lumbago: Pain in the muscles of the lower back.

Trotsky: See Carry On, Jeeves!.

mise en scène: a French term for a stage setting; generalized to refer to the background of any event or situation.

like the paper on the wall: See The Luck of the Bodkins.

Braid on Casual Water: Though James Braid wrote books on golf, this one is a Wodehouse invention. See A Glossary of Golf Terminology for casual water. The US magazine version has Hagen on Casual Water here (US golfer Walter Hagen, 1892–1969); the US book has Braid on Taking Turf instead.

kettle … steam the gum: Keggs does this to an envelope in A Damsel in Distress, ch. 22 (1919).

every other female voice … on the telephone: see A Damsel in Distress.

Salvini in “Othello”: Italian actor Tommaso Salvini (1829–1915) first essayed the role of Othello in 1856 and became famous for it in England and the USA as well as in Italy and in Russia, where Stanislavski saw him in the role in 1882, inspiring some of his theories about method acting. Wodehouse referred to him again in “The Reverent Wooing of Archibald” (see the excerpt labeled 28RW).

the pillow scene: See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

macaroon: Compare the description in “Jeeves and the Old School Chum” (1930; in Very Good, Jeeves, 1930):

I mean to say, when you reflect that the average woman considers she has lunched luxuriously if she swallows a couple of macaroons, half a chocolate éclair and a raspberry vinegar, is she going to be peevish because you do her out of a midday sandwich?

getting outside: See Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit.

mounted the stairs … first floor: In both US and UK magazine appearances and in both book collections, Wodehouse uses the British convention that the first floor is the first one above the ground floor.

Chesterfield: See Blandings Castle and Elsewhere.

subtitle: See The Old Reliable.

eggs of evil: Found in a few nineteenth-century volumes of sermons and theology of the kind Wodehouse describes from his childhood. The earliest so far found: The Homilist (1873).

Ethel M. Dell: popular British author of romance novels and stories (1881–1939), often mentioned by Wodehouse; see Bill the Conqueror.

welterweight: In British boxing at the time, at a fighting weight from 140 to less than 154 pounds. (New York State rules of 1920 set slightly higher weights of 147 to less than 160 pounds.)

knocking the stuffing out of him: The US magazine only has the rare term knocking him for a row of Portuguese ash-cans here, used also in The Small Bachelor, and not found so far in any other available source. Green’s Dictionary of Slang has an interesting citation from 1923 for a “Chinese ash can” referring to a small, powerful firecracker wrapped in tinfoil. I’m speculating here, but since firecrackers were often also made in Macao, at that time a Portuguese colony near Hong Kong, could this be the source of Wodehouse’s slang term?

vitriol: Concentrated sulfuric acid.

make him swallow himself: see Right Ho, Jeeves.

zimp: Spelled simp in US magazine only. See Ukridge.

pull: To strike the ball so that it veers in the direction from which one swings: to the left for a right-handed golfer.

cloth-headed: Stupid or thoughtless.

Walter J. Travis: (1862–1927): Australian-American amateur golfer, teacher, golf course architect.

saw the light: See The Code of the Woosters.

Glory! Glory!: More usually encountered as an audience response to a religious evangelist.

snifter: The apparent sense of snifter as “something good” has not so far been found in conventional or slang dictionaries; it seems likely to be Wodehouse’s nonce variant of “nifty.” Most commonly snifter is a small drink of liquor (e.g. “the hour of the morning snifter” at the Drones Club in “Fate” [1936]), or the pear-shaped drinking glass with a large bowl, a narrow top opening, and a short stem, used to concentrate the aroma of brandy or liqueurs.

none like her, none: See Sam the Sudden.

not worthy to polish the blade of her niblick: see Biblia Wodehousiana.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums